Þórkell Þórmóðsson

| Þórkell Þórmóðsson | |

|---|---|

| Died |

c. 1230 Vestrajǫrðr, near Skye |

| Cause of death | Killed in battle |

| Children | Three sons, including one named Þórmóðr |

| Parent(s) | Þórmóðr (father) |

| Notes | |

|

Þórkell's sons, and death, are known from Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar; his father's name is known from his patronym | |

Þórkell Þórmóðsson is a character from the mediaeval Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, a kings' saga composed in the last half of the 13th century. The saga relates that in about the year 1230, a Norwegian-Hebridean fleet sailed down through the Hebrides, where it attacked certain islands there, and proceeded on to the Isle of Man. As the fleet made its way southward through the Hebrides, several members fought a battle with Þórkell at Vestrajǫrðr, near Skye. The exact location of Vestrajǫrðr is unknown, although Loch Bracadale, Loch Dunvegan, and Loch Snizort, all located on the western coast of Skye, have been proposed as possible locations. According to the saga, Þórkell and two of his sons were slain in the encounter, however a third son, named Þórmóðr, managed to escape with his life. Early the next year, the fleet headed northwards through the Hebrides back home. When it approached the island of Lewis, a man named Þórmóðr Þórkelson fled for his life, leaving behind his wife and possessions to be taken by the marauding fleet.

In the late 19th century, it was suggested that the Þórmóðr Þórkelson that fled Lewis in 1231, was the same Þórmóðr Þórkelson who survived the battle at Vestrajǫrðr, in 1230. It is uncertain why Þórkell, and Þórmóðr, were singled out by the marauding fleet. One of the noted members of the fleet was Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of Mann and the Isles, who is known to have been at odds with his nephew, Guðrøðr Rögnvaldsson. One theory, put forward in the 19th century, asserts that Þórkell and Þórmóðr, had backed the side of Guðrøðr, and were killed by adherents of Óláfr.

It has also proposed that Þórkell and Þórmóðr could be descendants of another saga-character, Ljótólfr, who is recorded in the mediaeval Orkneyinga saga. Furthermore, it was asserted that all three men were ancestors of Clan MacLeod—that Ljótólfr's name is preserved in the surname: MacLeod; and that Þórkell's, and Þórmóðr's, names are preserved in the traditional branches of the clan: Sìol Thormoid, and Sìol Thorcaill. Another suggestion is that Þórkell was somehow related to the Skye MacNicols.

Sources

Þórkell Þórmóðsson is recorded in the mediaeval kings' saga Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar ("Hakon Hakon's son's Saga"). The saga was composed by Sturla Þórðarson, sometime around 1263–1284. Sturla based it on both written sources and oral traditions. The saga is preserved in several manuscripts that slightly differ from each other—these are: Eirspennill, the Flateyjarbók, the Frisbók, and the Skálholtsbók. According to twentieth-century historian Alan Orr Anderson, although the Eirspennill version may be of a later date than the others, it is the most authoritative, and likely represents an early form of the saga.[1]

Historical background

.png)

In the early 12th century, the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles encompassed the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. In 1156, Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of Mann and the Isles, fought an inconclusive naval battle with Somairle, Lord of Argyll, and the kingdom lost control of parts of the Inner Hebrides, although retained control of Skye. In 1187, Guðrøðr died, and had intended to that his young son Óláfr would succeed him. The Manx people, however, chose Guðrøðr's elder, although illegitimate son, Rögnvaldr. Bitter feuding between the two half-brothers in the late 12th and early 13th century severely weakened the kingdom. At one point, Rögnvaldr's son Guðrøðr drove Óláfr out of kingdom, only to be defeated by Óláfr, and then blinded and castrated by one of Óláfr's accomplices.

In the early 13th century, Alan, Lord of Galloway had sights set on the Isle of Man; his illegitimate son was married to the daughter of Rögnvaldr, King of Mann and the Isles.[2] Both Alan and his brother, Thomas, Earl of Atholl, backed Rögnvaldr against Rögnvaldr's half-brother, Óláfr.[3] In 1226, Óláfr ejected his brother from the Isle of Man, and ruled the kingdom for the next 11 years (Rögnvaldr was slain in 1229,[4] fighting against Óláfr).[5] Because of Óláfr's inability to control the warring in the Hebrides, Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway, promoted Óspakr, a descendant of Somairle, as king in the Isles.[note 1] Hákon gave Óspakr command of a fleet to establish himself in all of the Scottish islands, and according to historian G.W.S. Barrow, possibly Argyll and Kintyre as well.[8] Both Óláfr, and his nephew, Guðrøðr, accompanied the fleet as it sailed down through the Hebrides in the spring of 1230.[9]

If the saga accounts are to be believed, the fleet totalled eighty ships, and according to historian Richard Oram, this likely equates to a force of over three thousand men. When the fleet reached the southern Hebrides, several grandsons of Somairle, who had sided with Alan, were captured and taken prisoner. The fleet likely entered the Firth of Clyde in early June, and the force attacked the Isle of Bute. Although the Norwegian-Hebridean force was successful in its attack, word of Alan's approach with over 200 ships forced the invading fleet to retreat into the Hebrides. Óspakr later died, more than likely due to wounds received on Bute. Command of the fleet then fell to Óláfr, who used the force to suit his own needs, and regained control of the Isle of Man. The fleet overwintered on the island, and the following spring sailed northwards home. On the way, the forced attacked a contingent of Scots on Kintyre, suffering heavy casualties.[9] Guðrøðr was slain in 1231 on the island of Lewis; Óláfr died in 1237.

Saga narrative

The Eirspennill version of the saga relates that towards the end of winter, the Norwegian king, Hákon, summoned an assembly at his palace, and granted Uspak the title of king, and bestowed upon the him the royal name Hákon. The Norwegian king decided upon a plan to give Uspak an army to command in the Hebrides. In Spring, Hakon set out for Bergen, and upon his arrival ordered the preparation of the fleet. While preparations were under way, Óláfr came to the king, stating that he had fled from Mann because Ailín had driven him off his lands; he also stated that Ailín had made many threats to the Norwegians. Óláfr stayed in Bergen for several nights, before leaving for Orkney with Páll Bálkason. Before the fleet had left Orkney, it had swelled in size to twenty ships. When, Balki 'the Young' Pálsson, and Óttarr Snækollr, heard of this, they sailed south to Skye,[note 2] where they came upon Þórkell Þórmóðsson at Vestrajǫrðr, where they fought him. Þórkell was slain along with two of his sons; however, another son, named Þórmóðr, survived by leaping onto a cask which floated beside the ship, and was driven along the shore to Hattarskot.[note 3] After their victory, Óttarr Snækollr and Bálki 'the Young' sailed to meet Uspak and the fleet.[12]

After the death of Þórkell, the whole fleet sailed to the Sound of Islay, and was further strengthened by Hebrideans and grew to a size of eighty ships. The fleet sailed on to the Bute, where the force invaded the island and took the castle while suffering heavy casualties. The fleet then sailed to Kintyre, and Uspak fell ill and died. Óláfr then took control of the expedition, and they sailed south to the Isle of Man. The Norwegians left in the Spring, and sailed north to Kintyre; here they encountered a strong force of Scots and both sides lost many men during the ensuing battle. Following this, the fleet sailed north to Lewis and came upon Þórmóðr Þórkelson. Þórmóðr fled, his wife was taken as a captive of war, and all his treasure was seized.[note 4] The Norwegians then travelled to Orkney, and most of the fleet sailed back to Norway. Páll, however, remained behind in the Hebrides, where he was slain several weeks later.[14]

Commentary

There have been several proposed locations for Vestrajǫrðr, which translates from Old Norse as: "the western firth". Writing in 1871 of the history and traditions of Skye, Alexander Cameron noted the events surrounding Þórkell at Vestrajǫrðr, and stated that the location refers to Loch Bracadale.[15] Some years later in 1886, historian Alexander MacKenzie also noted the battle, and stated that the location "was said to be" Loch Bracadale.[16] In 1922, Anderson suggested that Vestrajǫrðr may equate to Loch Dunvegan.[11] Recently Peder Gammeltoft has equated Vestrajǫrðr to either Loch Dunvegan or Loch Snizort.[17] In the late 18th century, James Johnstone considered that Hattarskot refers to a promontory in Argyllshire or Ross.[18] Later in the 19th century, antiquarian F.W.L Thomas stated that Hattarskot specifically refers to Applecross, and theorised that Hattarskot was a Norse attempt to render Aporcrosan—an early form of the placename.[19][20][note 5] Gammeltoft suggested that Hattarskot referred to Gairloch.[22]

Thomas considered that Þórmóðr Þórkelson was the surviving son of Þórkell;[20] later at the beginning of the 20th century, historian William C. Mackenzie was of the same opinion.[5] According to 19th-century Norwegian historian Peter Andreas Munch, it is unclear why Þórkell was singled out and attacked by members of the Norwegian-Hebridean fleet; although, he suggested that it might have had to do with a personal feud between Þórkell and Páll.[23] Thomas stated that Þórkell seems to have backed the side of Guðrøðr, in opposition of Óláfr; since Páll's father, Balki, was a follower (a sheriff) of Óláfr, and Páll himself was a close companion of Óláfr.[19] W.C. Mackenzie noted that not long after the fleet forced Þórmóðr from Lewis, Guðrøðr took revenge on Páll, who had mutilated him years before. W.C. Mackenzie stated that it appears that Guðrøðr was seated on Lewis, and noted that Guðrøðr killed Páll on Skye, before being slain himself on Lewis days later.[5]

Proposed connection with Ljótólfr, and Clan MacLeod

Thomas proposed that Þórmóðr Þórkelson, and Þórkell Þórmóðsson, were ancestors of Clan MacLeod.[20] The Old Norse names Þórmóðr and Þórkell are the ultimate origin of the modern Scottish Gaelic names Tormod and Torcall.[24] Thomas noted that the traditionally the clan is said to have two branches—one is traditionally known in Scottish Gaelic as Sìol Thormoid ("Seed of Tormod"), the other is known as Sìol Thorcaill ("Seed of Torcall").[20] Historically, Sìol Thorcaill was the dominant family on Lewis from the Late Middle Ages to the end of the 16th century.[25] Sìol Thormoid has held lands in western Skye since the Late Middle Ages,[19] and descendants (in the female line) of the original chiefly line are still seated on the shores of Loch Dunvegan.[26] According to clan tradition, the two branches take their names from two brothers who were sons of the clan's founder—Torcall and Tormod, sons of Leod. However, the current understanding of the origin of these branches is that these two men were not brothers, but one was a grandson of the other—Torcall was the grandson of Tormod, who was the son of Leod.[27] Leod and his son, Tormod, do not appear in contemporaneous historical records; although Torcall does, in the mid 14th century.[28][29]

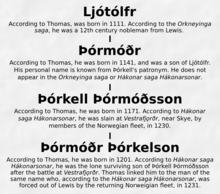

Thomas believed that the eponymous ancestor of the clan was Ljótólfr, a character in the mediaeval Orkneyinga saga,[25][30] which depicts him as a 12th-century nobleman from Lewis.[31] The currently accepted understanding of the clan's origin is that the clan's eponym was another man, named Leod (a name derived from the Old Norse Ljótr), who is thought to have flourished about a century after the time of Ljótólfr.[27] While the current understanding of Leod's ancestry does not include a man named Ljótólfr,[27] the 20th-century clan historian Alick Morrison considered it possible that Ljótólfr could be an ancestor, albeit on his distaff side.[30]

Thomas proposed that Þórmóðr Þórkelson was the surviving son of Þórkell Þórmóðsson; and that Þórkell Þórmóðsson was in turn the grandson of Ljótólfr. Thomas pointed out that, since the saga states that Þórkell left behind his wife and possessions on Lewis when he fled the returning fleet, the saga shows that Þórkell was a resident on that island.[20] Thomas theorised that a generation could be estimated to about 30 years, and noted that Þórkell was married in about 1231. Thomas estimated that Þórmóðr was born in 1201; his (supposed) father, Þórkell, in 1171; Þórkell's father Þórmóðr in 1141; and this man's father in 1111. Thomas concluded that Þórkell's father would have been born at about the same time as when Ljótólfr flourished on Lewis.[19]

In the 20th century, Gaelic scholar William Matheson suggested that Þórkell may have been related to the Skye MacNicols. Matheson noted that the name Torquil is found within MacNicol pedigrees, and that according to tradition, the clan possessed Lewis and Assynt before a MacLeod married a MacNicol heiress and gained the clan's lands. Matheson believed that the first MacLeod to bear the name, Torquil MacLeod, was the son of the MacNicol heiress of tradition, and that it was through her that the MacLeods of Lewis (Sìol Thorcaill) gained the name.[28]

Notes

- ↑ The exact identity of Óspakr is unknown,[6] although several historians have stated he was a son of Dubgall mac Somairle.[7]

- ↑ According to the Frisbók, the men that sailed to Skye were: Páll Bálki, son of the young king, and Óttarr Snækollr. The Flateyjarbók gives: Óttarr Snækollr, and Bálki the Young Pálsson. The Skálholtsbók gives: Bálki the Young, and Óttarr Snækollr.[10]

- ↑ The Flateyjarbók states that Þórmóðr leapt onto a rock, and floated by a ship.[11]

- ↑ The Frisbók, Flateyjarbók and Skálholtsbók, state that Þórmóðr was chased out of the islands, some of his retainers were slain, his baggage was taken, and his wife was taken as a captive of war.[13]

- ↑ Applecross first appears on record in about 1080, in the form of Aporcrosan. The placename is derived from both Pictish and Gaelic elements. The first element is the Pictish aber; the second is the Gaelic cros, combined with the diminutive suffix -an, which together mean "little cross".[21]

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ Anderson 1922: pp. lxi–lxii.

- ↑ Stringer 1998: p. 96.

- ↑ Barrow 1981: pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Sellar 2000: p. 192.

- 1 2 3 Mackenzie 1905: pp. 36–38.

- ↑ McDonald 2007: p. 158.

- ↑ McDonald 1997: p. 89.

- ↑ Barrow 1981: p. 110–111.

- 1 2 Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 250–252.

- ↑ Anderson 1922: p. 474.

- 1 2 Anderson 1922: p. 475.

- ↑ Anderson 1922: pp. 473–475.

- ↑ Anderson 1922: p. 478.

- ↑ Anderson 1922: pp. 475–478.

- ↑ Cameron 1871: p. 14.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1886: p. 50.

- ↑ Gammeltoft 2007: p. 486.

- ↑ Johnstone 1780: p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas 1874–76: pp. 506–507.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vigfusson 1887: v. 1. pp. xxxvii–xxxviii.

- ↑ Applecross, Encyclopedia.com, retrieved 24 February 2011. This webpage is a partial transcription of Mills, A. D. (2003), A Dictionary of British Place-Names, Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Gammeltoft 2007: p. 484.

- ↑ Munch 1860: pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Hanks; Hodges 2006: pp. 207, 263, 397, 410.

- 1 2 Thomas 1879–80: pp. 369–370, 379.

- ↑ Chief Hugh MacLeod of MacLeod, Associated Clan MacLeod Societies (www.clanmacleod.org), retrieved February 23, 2011

- 1 2 3 The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered, Associated Clan MacLeod Societies Genealogical Resources Center (www.macleodgenealogy.org), retrieved 8 December 2009. This webpage is a transcription of: Sellar, W. David H. (1997–1998), "The Ancestry of the MacLeods Reconsidered", Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Inverness, 60: 233–258.

- 1 2 The MacLeods of Lewis, Associated Clan MacLeod Societies Genealogical Resources Center (www.macleodgenealogy.org), retrieved 30 December 2009. This webpage is a transcription of: Matheson, William (1978–80), "The MacLeods of Lewis", Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Inverness, 51: 320–337.

- ↑ Robertson 1798: p. 48.

- 1 2 The Origin of Leod, Associated Clan MacLeod Societies Genealogical Resources Center (www.macleodgenealogy.org), retrieved 17 January 2010. This webpage is a transcription of: Morrison, Alick (1986), The Chiefs of Clan MacLeod, Edinburgh: Associated Clan MacLeod Societies, pp. 1–20.

- ↑ Anderson 1873: p. 106.

- Bibliography

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1922), Early Sources of Scottish History: A.D. 500 to 1286, 2, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd

- Anderson, Joseph, ed. (1873), The Orkneyinga saga, translated by Jón Andrésson Hjaltalín; Gilbert Goudie, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas

- Barrow, G.W.S. (1981), Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0-8020-6448-5

- Cameron, Alexander (1871), The History and Traditions of The Isle of Skye, Inverness: E. Forsyth

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005), Viking Empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2007), "Scandinavian naming-systems in the Hebrides—A way of Understanding how Scandinavians were in contact with Gaels and Picts?", in Smith, Beverley Ballin; Taylor, Simon; Williams, Gareth, West Over the Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300, The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economies and Cultures, 31, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1, ISSN 1569-1462

- Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Hardcastle, Kate (2006), Oxford Dictionary of Names (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-861060-1

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1886), The Celtic Magazine, 11, Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie

- Mackenzie, William Cook (1903), History of the Outer Hebrides: (Lewis, Harris, North and South Uist, Benbecula, and Barra), Paisley: Alexander Gardner

- McDonald, R. Andrew (1997), The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–1336, Edinburgh

- McDonald, R. Andrew (2007), Manx kingship in its Irish Sea setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan dynasty, Four Courts Press

- Moore, Arthur William (1890), The Surnames & Place-names of the Isle of Man, London: Elliot Stock

- Munch, Peter Andreas (1860), Chronica regvm Manniæ et insvlarvm: The Chronicle of Man and the Sudreys; edited from the manuscript codex in the British Museum; and with historical notes, Christiania: printed by Brøgger & Christie

- Oliver, J.R. (1860), Monumenta de insula manniae: or, A collection of national documents relating to the Isle of Man, 1, Douglas, Isle of Man: printed for the Manx Society

- Robertson, William (1798), An index, drawn up about the year 1629, of many records of charters, granted by the different sovereigns of Scotland between the years 1309 and 1413, most of which records have been long missing. With an introduction, giving a state, founded on authentic documents still preserved, of the ancient records of Scotland, which were in that kingdom in the year 1292. To which is subjoined, indexes of the persons and places mentioned in those charters, alphabetically arranged, Edinburgh: printed by Murray & Cochrane

- Sellar, W. David. H. (2000), "Hebridean Sea Kings: The Successors of Somerled, 1164–1316", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, R. Andrew, Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-86232-151-5

- Stringer, Keith J. (1998), "Periphery and Core in Thirteenth-Century Scotland: Alan son of Roland, Lord of Galloway and Constable of Scotland", in Grant, Alexander; Stringer, K.J., Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community: Essays presented to G.W.S. Barrow, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-585-06064-4

- Thomas, F.W.L. (1874–76), "Did the Northmen extirpate the Celtic Inhabitants of the Hebrides in the Ninth Century?" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 11

- Thomas, F.W.L. (1879–80), "Traditions of the Macaulays of Lewis" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 14

- Johnstone, James, ed. (1780), Anecdotes of Olave the Black, king of Man, and the Hebridean princes of the Somerled family, to which are added xviii, eulogies on Haco king of Norway / by Snorro Sturlson, poet to that monarch, now first published in the original Islandic from the Flateyan and other manuscripts ; with a literal version, and notes, Copenhagen: printed for the author

- Vigfusson, Gudbrand, ed. (1887), Icelandic sagas and other historical documents relating to the settlements and descents of the Northmen on the British Isles, 1, London: printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office by Eyre and Spottiswoode

- Vigfusson, Gudbrand, ed. (1887), Icelandic sagas and other historical documents relating to the settlements and descents of the Northmen on the British Isles, 2, London: printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office by Eyre and Spottiswoode