10 August (French Revolution)

| The Insurrection of 10 August 1792 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolution | |||||||

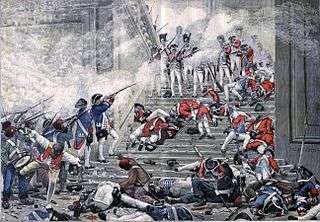

Prise du palais des Tuileries Jean Duplessis-Bertaux (1747–1819) National Museum of the Chateau de Versailles, 1793 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

• Antoine Joseph Santerre • François Joseph Westermann • Charles-Alexis Alexandre • Claude Fournier-L'Héritier • Claude François Lazowski |

• Louis XVI • Augustin-Joseph de Mailly • Karl Josef von Bachmann | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~20,000 12 cannons |

950 Swiss Guard 200 to 300 Gentlemen-at-arms Some royalist National Guards | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 200 to 400 killed |

600 killed 200 captured | ||||||

The Insurrection of 10 August 1792 was one of the defining events in the history of the French Revolution. The storming of the Tuileries Palace by the National Guard of the insurrectional Paris Commune and revolutionary fédérés from Marseilles and Brittany resulted in the fall of the French monarchy. King Louis XVI and the royal family took shelter with the Legislative Assembly, which was suspended. The formal end of the monarchy that occurred six weeks later was one of the first acts of the new National Convention. This insurrection and its outcome are most commonly referred to by historians of the Revolution simply as "the 10 August"; other common designations include "the journée of the 10 August" (French: journée du 10 août) or "the Second Revolution".

The context

The war declared on 20 April 1792 against the King of Bohemia and Hungary (Austria) started badly. The initial battles were a disaster for the French, and Prussia joined Austria in active alliance against France. The blame for the disaster was thrown first upon the king and his ministers (Austrian Committee), and secondly upon the Girondin's party.[1]

The Legislative Assembly passed decrees, sentencing any priest denounced by 20 citizens to immediate deportation (17 May), dissolving the King's guard on the grounds that it was manned by aristocrats (29 May), and establishing in the vicinity of Paris a camp of 20,000 national guardsmen (Fédérés) (8 June). The King vetoed the decrees and dismissed Girondins from the Ministry.[2] When the king formed a new cabinet mostly of constitutional monarchists (Feuillants), this widened the breach between the king on the one hand and the Assembly and the majority of the common people of Paris on the other. Events came to a head on 16 June when Lafayette sent a letter to the Assembly, recommending the suppression of the "anarchists" and political clubs in the capital.[3]

The King's veto of the Legislative Assembly's decrees was published on 19 June, just one day before the 3rd anniversary of the Tennis Court Oath which had inaugurated the Revolution. The popular journée of 20 June 1792 was organized to put pressure on the King. The King, appearing before the crowd, put on the bonnet rouge of liberty and drank to the health of the nation, but refused either to ratify decrees or to recall the ministers. The mayor of Paris, Pétion, was suspended, and on 28 June Lafayette left his post with the army and appeared before the Assembly to call on the deputies to dissolve the Jacobin Club and punish those who were responsible for the demonstration of 20 June.[4] It was a brave but belated gesture. It could do nothing against the universal distrust in which the hero of '89 was now held. The deputies indicted the general for deserting his command. The king rejected all suggestions of escape from the man who had so long presided over his imprisonment. The crowd burnt him in effigy in the Palais-Royal. There was no place for such as Lafayette beside that republican emblem, nor in the country which had adopted it. Within six weeks he was arrested whilst in flight to England, and immured in an Austrian prison.[5] He failed because it clashed with national sentiment. The inaction in which he had kept the armies for more than 2 months past seemed inexplicable. It had given the Prussians time to finish their preparations and concentrate upon the Rhine undisturbed.[6]

A decree of 2 July authorized National Guards, many of whom were already on their way to Paris, to come to the Federation ceremony; another of 5 July declared that in the event of danger to the nation all able-bodied men could be called to service and necessary arms requisitioned. Six days later the Assembly declared La patrie est en danger (The fatherland in danger).[7] Banners were placed in the public squares, bearing the words:

Would you allow foreign hordes to spread like a destroying torrent over your countryside! That they ravage our harvest! That they devastate our fatherland through fire and murder! In a word, that they overcome you with chains dyed with the blood of those whom you hold the most dear...

Citizens, the country is in danger! [8]

Toward the crisis

On 3 July Vergniaud gave a wider scope to the debate by uttering a terrible threat against the King's person: "It is in the King's name that the French princes have tried to rouse all the courts of Europe against the nation, it is to avenge the dignity of the King that the treaty of Pillnitz was concluded and the monstrous alliance formed between the Courts of Vienna and Berlin; it is to defend the King that we have seen what were formerly companies of the Gardes du Corps hurrying to join the standard of rebellion in Germany; it is to come to the assistance of the King that the émigrés are soliciting and obtaining employment in the Austrian army and preparing to stab their fatherland to the heart...it is in the name of the King that liberty is being attacked...yet I read in the Constitution, chapter II, section i, article 6: If the king place himself at the head of an army and turn its forces against the nation, or if he do not explicitly manifest his opposition to any such enterprise carried out in his name, he shall be considered to have abdicated his royal office." Vergniaud recalled the royal veto, the disorders which it had caused in the provinces, and the deliberate inaction of the generals who had opened the way to invasion; and he put it to the Assembly—though by implication rather than directly—that Louis XVI came within the scope of this article of the Constitution. By this means he put the idea of deposing the King into the minds of the public. His speech, which made an enormous impression, was circulated by the Assembly through all the departments.[9]

Evading the royal veto on an armed camp, the Assembly had invited National Guards from the provinces, on their way to the front, to come to Paris, ostensibly for the 14 July celebrations. These fédérés tended to have more radical views than the deputies who had invited them, and by mid-July they were petitioning the Assembly to dethrone the king. The fédérés were reluctant to leave Paris before a decisive blow had been struck, and the arrival on 25 July of 300 from Brest and five days later of 500 Marseillais, who made the streets of Paris echo with the song to which they gave their name, provided the revolutionaries with a formidable force.[10]

The Fédérés set up a central committee and a secret directory that included some of the Parisian leaders and thereby assured direct contact with the sections. Already (15 July) a coordinating committee had been formed of one federal from each department. Within this body soon appeared a secret committee of five members. Vaugeois of Blois, Debesse of the Drome, Guillaume of Caen and Simon of Strasbourg were names as little known in Paris as they are to history: but they were the authors of a movement that shook France. They met at Duplay's house in the Rue Saint-Honoré, where Robespierre had his lodgings, in a room occupied by their fifth member, Antoine, the mayor of Metz. They conferred with a group of section leaders hardly better known than themselves—the journalists Carra and Gorsas, Alexandre and Lazowski of the faubourg Saint-Marceau, Fournier "the American", Westermann (the only soldier among them), the baker Garin, Anaxagoras Chaumette and Santerre of the faubourg Saint-Antoine.[11] Daily meetings were held by the individual sections, and on 25 July the assembly authorized continuous sessions for them. On the 27th Pétion permitted a "correspondence office" to be set up in the Hôtel de Ville. Not all sections opposed the king, but passive citizens joined them, and on the 30th the section of the Théâtre Français gave all its members the right to vote. At the section meetings Jacobins and sans-culottes clashed with moderates and gradually gained the upper hand. On 30 July a decree admitted passive citizens to the National Guard.[12]

On 1 August came news of a manifesto signed by the duke of Brunswick, threatening as it did summary justice on the people of Paris if Louis and his family were harmed: "they will wreak an exemplary and forever memorable vengeance, by giving up the city of Paris to a military execution, and total destruction, and the rebels guilty of assassinations, to the execution that they have merited."[13] The Brunswick Manifesto became known in Paris on 1 August; that same day and the following days the people of Paris received news that Austrian and Prussian armies had marched into French soil. These two occurrences heated the republican spirit to revolutionary fury.[12]

Insurrection threatened to break out on the 26th, again on the 30th. It was postponed both times through the efforts of Pétion, who was to present the section petitions to the Assembly on 3 August. On August 4th, the "section of 300" gave an ultimatum to the Legislative assembly.[14] Of the forty-eight sections of Paris, all but one concurred. Pétion informed the Legislative Assembly that the sections had "resumed their sovereignty" and that he had no power over the people other than that of persuasion. The faubourg Saint-Antoine, section of the Quinze-Vingts, gave the Assembly until 9 August to prove itself. On the 9th it refused even to indict Lafayette. That night the tocsin rang.[15]

The insurrection

Throughout the night of 9 August the sections sat in consultation. At 11 o'clock the Quinze-Vingts section proposed that each section should appoint three of its members on to a body with instructions "to recommend immediate steps to save the state" (sauver la chose publique). During the night 28 sections answered this invitation. Their representatives constituted the Insurrectional Commune.[16] Carra and Chaumette went to the barracks of the Marseilles Fédérés in the section of the Cordeliers, while Santerre roused the faubourg Saint-Antoine, and Alexandre the faubourg Saint-Marceau.[6]

The municipality was already in session. From midnight till three o'clock next morning the old and the new, the legal and the insurrectional communes, sat in adjoining rooms at the Town Hall (Hôtel de Ville). The illegal body organized the attack on Tuileries. The legal body, by recalling the officer in charge of the troops at the Tuileries, disorganized its defense. Between six and seven in the morning this farcical situation was brought to an end. The Insurrectional Commune informed the municipal body, in a formally worded resolution, that they had decided upon its suspension; but they would retain the mayor (Pétion), the procureur (Manuel), the deputy-procureur (Danton), and the administrators in their executive functions.[16] The resolution stated that "When the People puts itself into a state of insurrection, it withdraws all powers and takes it to itself."[17] Within an hour of their seizure of the Town Hall the attack on the palace began.

Tuileries defenses

It might be thought that Paris was running no great risk in attacking the Tuileries. Such was not the general opinion at the time. The king had failed to buy off the popular leaders. According to Malouet, thirty-seven thousand pounds had been paid to Pétion and Santerre for worthless promises to stop the insurrection. He rejected the last-minute advice, not only of Vergniaud and Guadet, who were now alarmed by a turn of affairs they themselves brought about, but also of his loyal old minister Malesherbes, to abdicate the throne. He was determined to defend the Tuileries. His supporters had anticipated and prepared for the attack long beforehand, and were confident of success. A plan of defense, drawn up by a professional soldier, had been adopted by the Paris department on 25 June: for it was their official duty to safeguard the Executive Power. The palace was easy to defend. It was garrisoned by the only regular troops on either side—950 veteran Swiss mercenaries (rumor made them four times as many); these were backed by 930 gendarmes, 2000 national guards, and 200–300 Chevaliers de Saint Louis, and other royalist volunteers. Five thousand men should have been an ample defense; though it appears that, by some oversight, they were seriously short of ammunition. Police spies reported to the commune that underground passages had been constructed by which additional troops could be secretly introduced from their barracks.[16] Mandat, the commander of the National Guard, was not very sure of his National Guard, but the tone of his orders was so resolute that it seemed to steady the troops. He had stationed some troops on the Pont Neuf so as to prevent a junction between the insurgents on the two sides of the river, which could prevent any combined movement on their part.[17]

This, then, was no Bastille affair. The popular leaders might well hesitate to throw an uncertain number of half-trained and untried volunteers, followed by an undisciplined mob armed with pikes, against so formidable a fortress. The supporters of the throne might well expect victory.[18]

Dislocation of the defense

Three men were in the palace, late that night, whose presence should have guaranteed the safety of the royal family—Pétion, the mayor of Paris, Roederer, the procureur of the Paris department, and Mandat, the commander of the National Guard and the officer in charge of the troops detailed for the defense of the Tuileries. All three failed the king. Pétion professed that he had to come to defend the royal family; but about 2 in the morning, hearing himself threatened by a group of royalist gunners, he obeyed summons to the Parliament-house, reported that all precautions had been taken to keep the peace, and retired ingloriously to the Mairie, where (as he said afterwards) he was confined on the orders of the Insurrectional Commune. Roederer's first act was to assure the royal family that there would be no attack. His second act, when a series of bulletins from Blondel, the secretary of the department, made it clear that an attack was imminent, was to persuade Louis to abandon the defense of the palace and to put himself under the protection of the assembly. Mandat, after seeing to the defense of the palace, was persuaded by Roederer (in the third and fatal mistake of the Tuileries defense) to obey a treacherous summons from the Town Hall.[18] Mandat knew nothing of the formation of the Insurrectional Commune, and thus he departed without any escort. He was put under arrest, and shortly thereafter murdered. His command was transferred to Santerre.[17]

Thus, when at about seven in the morning the head of the federal column was seen debouching on the back of the palace, there was no one to order the defense. Louis, sleepily reviewing his garrison, "in full dress, with his sword at his side, but with the powder falling out his hair," was greeted by some of the National Guards with cries of "Vive la nation!" and "A bas le véto!". Louis made no reply and went back to the Tuileries. Behind him quarrels were breaking out in the ranks. The gunners loudly declared they would not fire on their brethren.[17]

Hating violence, and dreading bloodshed, Louis listened willingly to Roederer's suggestion that he should abandon the defense of the palace. The queen urged in vain that they should stay and fight. Before even a single shot had been fired, the royal family were in sad retreat across the gardens to the door of the Assembly. "Gentlemen," said the king, "I come here to avoid a great crime; I think I cannot be safer than with you." "Sire," replied Vergniaud, who filled the chair, "you may rely on the firmness of the national assembly. Its members have sworn to die in maintaining the rights of the people, and the constituted authorities." The king then took his seat next the president. But Chabot reminded him that the assembly could not deliberate in the presence of the king, and Louis retired with his family and ministers into the reporter's box behind the president.[19] There, the king was given a seat and he listened, with his customary air of bland indifference, whilst the deputies discussed his fate. The queen sat at the bar of the House, with the Dauphin on her knees—to her, at least, the tragedy of their situation was clearly apparent.[18]

Assault on the Tuileries

The incentive for resistance fell away with the king's departure. The means of defense had been diminished by the departure of the National Guardsmen who escorted the king. The gendarmerie left their posts, crying "Vive la nation!", and the National Guard's inclination began to move towards the insurgents. On the right bank of the river, the battalions of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and, on the left, those of the Faubourg Saint-Marcel, the Bretons, and the Marseilles fédérés, marched forth as freely as if going to parade. At many places that had been ordered guarded, no resistance was put up at all, like at the Arcade Saint-Jean, the passages of the bridges, along the quays, and in the court of the Louvre. An advance guard consisting of men, women, and children, all armed with cutters, cudgels, and pikes, spread over the abandoned Carrousel, and towards eight o'clock the advance column, led by Westerman, appeared in front of the palace.[20]

The assault on the Palace begun at eight o'clock in the morning. As per the King's orders, the Swiss troops had retired into the interior of the building, and the defense of the courtyard had been left entirely to the National Guard. The Marseillais rushed in, fraternized with the gunners of the National Guard, reached the vestibule, ascended the grand staircase and called on the Swiss Guard to surrender. "Surrender to the Nation!", shouted Westermann in German. "We should think ourselves dishonored!" was the reply.[21] "We are Swiss, the Swiss do not part with their arms but with their lives. We think that we do not merit such an insult. If the regiment is no longer wanted, let it be legally discharged. But we will not leave our post, nor will we let our arms be taken from us."[20]

The Swiss filled the windows of the château, and stood motionless. The two bodies confronted each other for some time, without either of them making a definitive move. A few of the assailants advanced amicably, and the Swiss threw some cartridges from the windows as a token of peace. The insurgents penetrated as far as the vestibule, where they were met by other defenders of the château. The two bodies of troops remained facing each other on the staircase for three-quarters of an hour. A barrier separated them, and there the combat began, although it is unknown which side took the initiative. [22] The Swiss, firing from above, cleaned out the vestibule and the courts, rushed down into the square and seized the cannon; the insurgents scattered out of range. The bravest, nevertheless, rallied behind the entrances of the houses on the Carrousel, threw cartridges into the courts of the small buildings and set them on fire. Then the Swiss attacked, stepped over the corpses, seized the cannon, recovered possession of the royal entrance, crossed the Place du Carrousel, and even carried off the guns drawn up there.[21] As at the Bastille, the cry of treachery went up and the attackers assumed to have been ambushed and henceforth the Swiss were the subject of violent hatred on the part of sans-culottes.[23][24]

At that moment the battalions of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine arrived, and the reinforced insurgents pushed the Swiss back into the palace. Louis, hearing from the manége the sound of firing, wrote on a scrap of paper: "The king orders the Swiss to lay down their arms at once, and to retire to their barracks." To obey this order at such a moment meant almost certain death and Swiss officers in command realized the futility of it in the midst of heavy fighting and did not immediately act upon it. However, the position of the Swiss Guard soon became untenable as their ammunition ran low and casualties mounted. The King's note was then produced and the defenders were ordered to disengage. The main body of Swiss Guards fell back through the palace and retreated through the gardens at the rear of the building, some sought sanctuary in the Parliament House: some were surrounded, carried off to the Town Hall, and put to death beneath the statue of Louis XIV. Out of the nine hundred only three hundred survived.[25]

The massacre also included the male courtiers and members of the palace staff. However, no female members of the court seem to have been killed during the massacre. According to Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan, the ladies-in-waiting were gathered in a room in the queen's apartment, and when they were spotted, a man prevented an attack upon them by exclaiming, in the name of Petion: "Spare the women! Don't disgrace the nation!"[26] As the queen's entire household was gathered in her apartment, this may also have included female servants. Campan also mentioned two maids outside of this room, neither of whom was killed despite a male member of the staff being murdered beside them, again prevented by the cry: "We don't kill women."[26] The ladies-in-waiting were according to Campan escorted to prison.[26]

The total losses on the king's side were perhaps eight hundred. On the side of the insurgents three hundred and seventy-six were either killed or wounded. Eighty-three of these were fédérés, and two hundred and eighty-five members of the National Guard: common citizens from every branch of the trading and working classes of Paris. These included hair-dressers and harness-makers, carpenters, joiners, and house-painters, tailors, hatters, and boot-makers, locksmiths, laundry-men, and domestic servants. Two women combatants were among the wounded.[25]

Aftermath

The crisis of the summer of 1792 was a major turning-point of the Revolution. By overthrowing the monarchy, the popular movement had effectively issued the ultimate challenge to the whole of Europe; internally, the declaration of war and overthrow of the monarchy radicalized the Revolution. The political exclusion of "passive" citizens now called to defend the Republic was untenable. If the Revolution was to survive it would have to call on all the nation’s reserves.[27]

A second revolution had, indeed, occurred, ushering in universal suffrage and, in effect, a republic. But it did not have the warm and virtually unanimous support that the nation had offered the first. Events since 1789 had brought difference and divisions: many had followed the refractory priests; of those who remained loyal to the Revolution some criticized 10 August, while others stood by, fearing the day’s aftermath. Those who had actually participated in the insurrection or who unhesitatingly approved it were few in number, a minority resolved to crush counter-revolution by any means.[28]

Legislative Assembly

The impact of events on the Assembly was almost as striking. Over half of its members fled and on the evening 10 August only 284 deputies were in their seats.[29] The Assembly looked on anxiously at the vicissitudes of the struggle. So long as the issue was doubtful, Louis XVI was treated like a king. But as soon as the insurrection was definitely victorious, the Assembly announced the suspension of the King. The King was now placed under a strong guard. The Assembly would have liked to assign him the Palace of the Luxembourg, but the insurgent Commune demanded that he should be taken to the Temple, a smaller prison, which would be easier to guard.[30]

14 July had saved the Constitutional Assembly, 10 August passed sentence on the Legislative Assembly: the day's victors intended to dissolve the Assembly and keep power in their own hands. But because the new Commune, composed of unknowns, hesitated to alarm the provinces, the Girondins were kept and the Revolution was mired in compromise. The Assembly remained for the time being but recognized the Commune, increased through elections to 288 members. The Assembly appointed a provisional Executive Council and put Monge and Lebrun-Tondu on it, along with several former Girondin ministers. The Assembly voted that the Convention should be summoned and elected by universal suffrage to decide on the future organization of the State.[31] One of its first acts was to abolish the monarchy.

Social changes

With the fall of the Tuileries the face of Parisian society underwent an abrupt change. The August insurrection greatly increased sans-culotte influence in Paris. Whereas the old Commune had been predominantly middle class, the new one contained twice as many artisans as lawyers—and the latter were often obscure men, very different from the brilliant barristers of 1789. Moreover, the Commune itself was little more than "a sort of federal parliament in a federal republic of 48 states". It had only a tenuous control over the Sections, which began practicing the direct democracy of Rousseau. "Passive" citizens were admitted to meetings, justices of the peace and police officers dismissed and the assemblée générale of the Section became, in some cases, a "people’s court", while a new comité de surveillance hunted down counter-revolutionaries. For the Parisian nobility it was 10 August 1792 rather than 14 July 1789 that marked the end of the ancien régime.[29]

The victors of 10 August were concerned first with establishing their dictatorship. The Commune immediately silenced the opposition press, closed the toll gates, and by repeated house visits seized a number of refractory priests and aristocratic notables. On 11 August the Legislative Assembly gave municipalities the authority to arrest suspects.[32] The volunteers were preparing to leave to the front and the rumors spread rapidly that their departure was to be the signal for prisoners to stage an uprising. The wave of executions in prisons followed, what later was called as September Massacres.[33]

The war

Text reads: HELVETIUM FIDEI AC VIRTUTI (To the loyalty and bravery of the Swiss)

As if to convince the revolutionaries that the insurrection of 10 August had decided nothing, the Prussian army crossed the French frontier on the 16th. A week later the powerful fortress of Longwy fell so quickly that Vergniaud declared it to have been handed over to the enemy. By the end of the month the Prussians were at Verdun, the last fortress barring the road to Paris, and in the capital there was a well justified belief that Verdun, too, would offer no more than a token resistance. The war, which had appeared to bring the triumph of the Revolution, now seemed likely to lead it to disaster.[34]

On 2 September the alarm gun was fired and drums beat the citizens to their Sections again. The walls of Paris were plastered with recruiting posters whose opening sentence, "To arms, citizens, the enemy is at our gates!" was taken literally by many readers. In the Assembly, Danton concluded the most famous of all his speeches: "De l’audace, encore de l’audace, toujours de l’audace, et la France est sauvée!" (Audacity, and yet more audacity, and always audacity, and France will be saved!) Once more the sans-culottes responded and in the next three weeks, 20,000 marched from Paris for the defence of the Revolution.[35]

References

- ↑ Thompson 1959, p. 267.

- ↑ Soboul 1974, p. 245.

- ↑ Pfeiffer 1913, p. 221.

- ↑ Soboul 1974, p. 246.

- ↑ Thompson 1959, p. 275.

- 1 2 Mathiez 1929, p. 159.

- ↑ Hampson 1988, p. 145.

- ↑ McPhee 2002, p. 96.

- ↑ Mathiez 1929, p. 155.

- ↑ Hampson 1988, p. 146.

- ↑ Thompson 1959, p. 280.

- 1 2 Lefebvre 1962, p. 230.

- ↑ McPhee 2002, p. 97.

- ↑ Camille Bloch, ed., La Révolution Française, no. 27 (1894), 177–82

- ↑ Lefebvre 1962, p. 231.

- 1 2 3 Thompson 1959, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 4 Madelin 1926, p. 267.

- 1 2 3 Thompson 1959, p. 287.

- ↑ Mignet 1824, p. 287.

- 1 2 Taine 2011, p. 298.

- 1 2 Madelin 1926, p. 270.

- ↑ Mignet 1824, p. 298.

- ↑ Hampson 1988, p. 147.

- ↑ Rude 1972, p. 104.

- 1 2 Thompson 1959, p. 288.

- 1 2 3 Madame Campan, Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France, Project Gutenberg

- ↑ McPhee 2002, p. 98.

- ↑ Lefebvre 1962, p. 234.

- 1 2 Hampson 1988, p. 148.

- ↑ Mathiez 1939, p. 159.

- ↑ Lefebvre 1962, p. 238.

- ↑ Lefebvre 1962, p. 235.

- ↑ Soboul 1974, p. 262.

- ↑ Hampson 1988, p. 151.

- ↑ Hampson 1988, p. 152.

Sources

- Aulard, François-Alphonse (1910). The French Revolution, a Political History, 1789–1804, in 4 vols. Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hampson, Norman (1988). A Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-710-06525-6.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1962). The French Revolution: from its Origins to 1793. vol. I. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08599-0.

- Madelin, Louis (1926). The French Revolution. London: William Heinemann Ltd.

- Mathiez, Albert (1929). The French Revolution. New York: Alfred a Knopf.

- McPhee, Peter (2002). The French Revolution 1789–1799. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-199-24414-6.

- Mignet, François (1824). History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814. Project Gutenberg EBook.

- Pfeiffer, L. B. (1913). The Uprising of June 20, 1792. Lincoln: New Era Printing Company.

- Rude, George (1972). The Crowd in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Soboul, Albert (1974). The French Revolution: 1787–1799. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-47392-2.

- Taine, Hippolyte (2011). The Origins of Contemporary France, Volume 3. Project Gutenberg EBook.

- Thompson, J. M. (1959). The French Revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 10th of August 1792. |

- The document by which the National Assembly formally deposed Louis XVI and called for the Convention, translated into English.