1877 Wimbledon Championship

| 1877 Wimbledon Championship | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date | 9–19 July |

| Edition | 1st |

| Category | Grand Slam |

| Draw | 22S |

| Surface | Grass / Outdoor |

| Location |

Worple Road SW19, Wimbledon, London, United Kingdom |

| Venue | All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club |

| Champions | |

| Singles | |

|

| |

The 1877 Wimbledon Championship was a men's tennis tournament held at the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club (AEC & LTC) in Wimbledon, London. It was the world's first official lawn tennis tournament, and was later recognised as the first Grand Slam tournament or "Major". The AEC & LTC had been founded in July 1868, as the All England Croquet Club; lawn tennis was introduced in February 1875 to compensate for the waning interest in croquet. In June 1877 the club decided to organise a tennis tournament to pay for the repair of its pony roller, needed to maintain the lawns. A set of rules was drawn up for the tournament, derived from the first standardised rules of tennis issued by the Marylebone Cricket Club in May 1875.

The Gentlemen's Singles competition, the only event of the championship, was contested on grass courts by 22 players who each paid one guinea to participate. The tournament started on 9 July 1877, and the final – delayed for three days by rain – was played on 19 July in front of a crowd of about 200 people who each paid an entry fee of one shilling. The winner received 12 guineas in prize money and a silver challenge cup, valued at 25 guineas, donated by the sports magazine The Field. Spencer Gore, a 27-year-old rackets player from Wandsworth, became the first Wimbledon champion by defeating William Marshall, a 28-year-old real tennis player, in three straight sets in a final that lasted 48 minutes. The tournament made a profit of £10 and the pony roller remained in use. An analysis made after the tournament led to some modifications of the rules regarding the court dimensions.

Background

Origins of lawn tennis

The origin of tennis lies in the monastic cloisters in 12th-century France,[lower-alpha 1] where the ball was struck with the palm of the hand in a game called jeu de paume.[3][4] Rackets were introduced to the game in the early 16th century.[lower-alpha 2] This original version of tennis, now called "real tennis", was mostly played indoors and popular among the royalty and gentry, while a crude outdoor version called longue paume was played by the populace.[7][8] The prominence of the game declined in the 17th and 18th centuries, although there are sporadic mentions of a "long tennis" or "field tennis" version in the second half of the 18th century.[9][10]

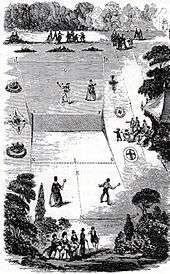

Between 1858 and 1873 several people in Victorian England experimented with a lawn version of tennis.[11][12][lower-alpha 3] Major Harry Gem and Augurio Perera demonstrated their game of Pelota (Spanish for ball) and in 1872 created the world's first lawn tennis club at Leamington Spa.[13][15] In February 1874 Major Clopton Wingfield introduced his version of lawn tennis, called Sphairistikè; on his patent application,[lower-alpha 4] he described it as a "New and Improved Court for Playing the Ancient Game of Tennis", and its rules were published in an eight-page booklet.[18] Wingfield is widely credited with popularising the new game through his energetic promotional efforts.[14][19][20][21] The Sphairistikè court was hourglass-shaped, wider at the baseline than at the net.[22] The service was made from a single side in a lozenge shaped box situated in the middle of the court and it had to bounce beyond the service line.[23] In November 1874 Wingfield published a second, expanded edition of The Book of the Game, which had 12 rules and featured a larger court and a slightly lower net.[24][25]

All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club

The All England Croquet Club was founded on 23 July 1868 by six gentlemen at the offices of The Field, a weekly country and sports magazine.[26][lower-alpha 5] After a yearlong search a suitable ground of four acres of meadowland was located between the London and South Western Railway and Worple Road in Wimbledon, then an outer suburb of London.[28][lower-alpha 6] The club's committee decided on 24 September 1869 to lease the ground and paid £50 rental for the first year, a fee which increased to £75 and £100, respectively, over the following two years.[30] The increasing rent, coupled with a waning interest in the sedate sport of croquet, was causing the club financial difficulties. In February 1875 it decided to introduce lawn tennis at its grounds to capitalise on the growing interest in this new sport and generate additional revenue.[31][32] The proposal was made by Henry Jones, a sports writer who published extensively in The Field under his nom de plume "Cavendish" and who had joined the club in 1869. The introduction of lawn tennis was approved at the annual meeting and the club's membership fee was set at two guineas to cover both sports.[30] At a cost of £25, one croquet lawn was converted to a tennis court; soon after its completion on 25 February 1875, a dozen new club members joined.[33] In 1876 four more lawns, a third of the ground, were handed over to lawn tennis to address the increase in new members. A committee member, George Nicol, was appointed to deal exclusively with lawn tennis affairs.[31][34] Lawn tennis had become so popular that on 14 April 1877 the name of the club was formally changed, at the suggestion of founding member John H. Hale, to the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club (AEC<C).[34]

Rules of lawn tennis

On 3 March 1875 the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), in its capacity as the governing body for rackets and real tennis, convened a meeting at Lord's Cricket Ground to test the various versions of lawn tennis with the aim to standardise the game's rules.[35][lower-alpha 7] Wingfield was present to demonstrate Sphairistikè, as was John H. Hale, who presented his version called Germains Lawn Tennis; there is no record of either Gem or Perera being present to showcase Pelota.[37] After the meeting, the MCC Tennis Committee was tasked with framing the rules.[lower-alpha 8] On 29 May 1875 the MCC issued the Laws of Lawn Tennis, the first unified rules for lawn tennis, which were adopted by the club on 24 June.[39][34] These were significantly based on the rules introduced by Wingfield in February 1874 and published in his rule-booklet titled Sphairistikè or Lawn Tennis.[40] The MCC adopted Wingfield's hourglass-shaped court as well as the rackets method of scoring, in which the player who first scores 15 points wins the game and only the server ("hand-in") was able to score.[29][41] The height of the net was set at 5 ft (1.52 m) at the posts and 4 ft (1.22 m) in the centre.[42] Various aspects of these rules, including the characteristic court shape and the method of scoring, were the subject of prolonged debate in the press.[43][31] The MCC rules were not universally adhered to following its publication and, among others, the Prince's Club in London stuck to playing on rectangular courts.[44][45]

Tournament

On 2 June 1877, at the suggestion of the All England Club secretary and founding member John H. Walsh, the club committee decided to organise a lawn tennis championship for amateurs, a Gentlemen's Singles event,[lower-alpha 9] which they hoped would generate enough funds to repair the broken pony roller that was needed for the maintenance of the lawns.[20] This championship became the world's first official lawn tennis tournament,[lower-alpha 10] and the first edition of what would later be called a Grand Slam tournament (or "Major").[47][lower-alpha 11] The committee agreed to hold the tournament on the condition that it would not endanger the club's limited funds; to ensure this, Henry Jones persuaded 20 members and friends of the club to guarantee a part of the tournament's financial requirement and made himself responsible for the remaining amount.[49] Jones investigated all potential tournament locations in and around London but came to the conclusion that no other ground was more suitable than the Wimbledon premises at Worple Road. As a consequence, the remaining croquet lawns were converted to tennis courts.[50]

Announcement

The first public announcement of the tournament was published on 9 June 1877 in The Field magazine under the header Lawn Tennis Championship:[12][51][52]

The All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club, Wimbledon, propose to hold a lawn tennis meeting, open to all amateurs, on Monday, July 9th and following days.[lower-alpha 12] Entrance fee, £1 1s 0d. Names and addresses of competitors to be forwarded to the Hon. Sec. A.E.C. and L.T.C. before Saturday, July 7, or on that day before 2.15 p.m. at the club ground, Wimbledon. Two prizes will be given – one gold champion prize to the winner, one silver to the second player. The value of the prizes will depend on the number of entries, and will be declared before the draw; but in no case will they be less than the amount of the entrance money, and if there are ten and less than sixteen entries, they will be made up to £10 10s and £5 5s respectively.– Henry Jones – Hon Sec of the Lawn Tennis sub-committee

Players were instructed to provide their own racquets and wear shoes without heels.[56] The announcement also stated that a programme would be available shortly with further details, including the rules to be adopted for the meeting.[57] Invitations were sent to prospective participants. Potential visitors were informed that those arriving by horse and carriage should use the entrance at Worple Road while those who planned to come by foot were advised to use the railway path.[58] Upon payment of the entrance fee, the participants were allowed to practise before the Championship on the twelve available courts with the provision that on Saturdays and during the croquet championship week, held the week before the tennis tournament, the croquet players had the first choice of courts. Practice balls, similar to the ones used for the tournament, were available from the club's gardener at a price of 12s per dozen balls.[57] John H. Walsh, in his capacity as editor of The Field, persuaded his employer to donate a cup worth 25 guineas for the winner; the Field Cup[lower-alpha 13] The cup was made of sterling silver and had the inscription: The All England Lawn Challenge Cup – Presented by the Proprietors of The Field – For competition by Amateurs – Wimbledon July 1877.[61] On 6 July 1877, three days prior to the start of the tournament, a notice was published in The Times:

Next week at the All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club Ground a Lawn Tennis Championship Meeting will be held. The ground is situated close to the Wimbledon Station on the South Western Railway, and is sufficiently large for the erection of thirty "courts".[lower-alpha 14] On each day the competition will begin at 3.30, the first ties, of course, beginning on Monday. The Hon. Sec. of the meeting is Mr. J.H. Walsh, while Mr. H. Jones will officiate as referee. The entries are numerous.[62]

Rules

The committee of the club was not satisfied with certain aspects of the 1875 MCC unified rules.[64] To address these perceived shortcomings, a sub-committee consisting of Charles Gilbert Heathcote,[lower-alpha 15] Julian Marshall and Henry Jones was set up on 2 June 1877, to establish the rules applicable for the upcoming tournament. They reported back on 7 June with a new set of rules, derived but significantly different from those published by the MCC; in order not to offend the MCC, these rules were declared "provisional" and valid only for the championship:[66][67][62]

- The court will have a rectangular shape with outer dimensions of 78 by 27 feet (23.8 by 8.2 m).

- The net will be lowered to 3 feet 3 inches (0.99 m) in the centre.

- The balls will be 2 1⁄2 to 2 5⁄8 inches (6.4 to 6.7 cm) in diameter and 1 3⁄4 ounces (50 g) in weight.

- The real tennis method of scoring by fifteens (15, 30, 40) will be adopted.[lower-alpha 16]

- The first player to win six games wins the set with 'sudden death' occurring at five games all except for the final, when a lead of two games in each set is necessary.

- Players will change ends at the end of a set unless otherwise decreed by the umpire.

- The server will have two chances at each point to deliver a correct service and must have one foot behind the baseline.

These rules, drawn up by the club for this initial tournament, were eventually adopted for the entire sport and, with only slight modifications, have retained their validity.[65] All matches during the tournament were played as best-of-five sets.[58]

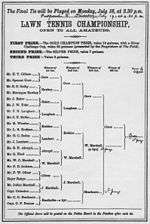

Play

In accordance with the All England Regulations for the Management of Prize Meetings, the draw for the 22 entrants was made on Saturday, 7 July 1877, at 3:30 p.m. in the club's pavilion. H.T. Gillson had the distinction of being the first player in the history of modern tennis to be drawn for a tournament. The posts, nets and hand-stitched, flannel-covered India-rubber balls for the tournament were supplied by Jefferies & Co from Woolwich, while the rackets used were an adaptation of those used in real tennis, with a small and slightly lopsided head.[68][69][lower-alpha 17] The ball-boys kept the tennis balls, 180 of which were used during the tournament, in canvas wells.[72] The umpires who were provided for the matches sat on chairs which in turn were placed on small tables of 18 inches height to give them a better view of the court.[58]

The tournament began on Monday, 9 July 1877, at 3:30 p.m. and daily programmes[lower-alpha 18] were available for sixpence.[73] On the first day, in sunny weather, ten matches were played, which completed the first round. Full match scores were published on the notice board inside the pavilion.[58] F.N. Langham, a Cambridge tennis blue, was given a walkover in the first round when C.F. Buller, an Etonian and well-known rackets player, did not appear. Julian Marshall became the first player to win a five-set match when he fought back from being two sets down against Captain Grimston. Spencer Gore, a 27-year-old rackets player from Wandsworth and at the time a land agent and surveyor by profession, won his first round match against Henry Thomas Gillson in straight sets.[74] The five second-round matches were played on Tuesday, 10 July, again in fine weather. Charles Gilbert Heathcote had a bye in the second round. J. Lambert became the first player in Wimbledon Championships' history to retire a match, conceding to L.R. Erskine after losing the first two sets. Julian Marshall again won a five-set match, this time against F.W. Oliver, while Gore defeated Montague Hankey in four sets.[1][74]

The quarter-finals were played on Wednesday, 11 July, before a larger number of spectators than had attended the previous matches. Start of play was delayed from the scheduled 3:30 p.m. due to strong winds.[75] Gore defeated Langham in four sets, William Marshall beat Erskine, also in four sets, and Julian Marshall, who injured his knee during the match after a fall, lost to Heathcote in straight sets.[75] The quarter-final matches left three players, instead of four, in the draw for the semi-finals scheduled for Thursday.[lower-alpha 19] To solve the situation lots were drawn and Marshall, a 28-year-old architect and Cambridge real tennis blue, was given a bye to the final. His opponent would be Gore, who defeated Heathcote in straight sets in the only semi-final played.[78] When the semi-final stage had concluded on Thursday, 12 July, play was suspended until next Monday, 16 July, to avoid a clash with the popular annual Eton v Harrow cricket match that was played at Lord's on Friday and Saturday.[62][79]

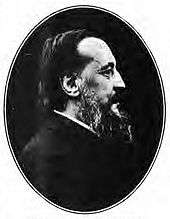

The final was postponed from its scheduled start on Monday at 4 p.m. until Thursday, 19 July, at 3:30 p.m. because of rain. On Thursday it was still showery, causing the final to be further delayed by an hour. It began on a dead and slippery court in front of about 200 spectators.[lower-alpha 20] There was a temporary three-plank stand on one side of the court offering seating to about thirty people.[80][lower-alpha 21] Marshall won the toss, elected to serve first and was immediately broken by Gore. After the first set was won by Gore, it started to rain for a quarter of an hour; this further softened the ground and affected the quality of play. The final lasted 48 minutes, and Spencer Gore won the inaugural championship against William Marshall in three straight sets of 15, 13, and 20 minutes respectively.[82][83] En route to the title Gore had won 15 sets and lost two and won 99 games for the loss of 46.[84] Gore, the volley specialist, had beaten the baseline player, at a time when volleying was considered by some to be unsporting.[84][lower-alpha 22] Some tried to outlaw the volley and a discussion on its merits took place in The Field for weeks after the tournament.[86]

The final was followed by a play-off match for 2nd place between Marshall and Heathcote. The players could not fix another date for the match and decided to play it straight away. By agreement, the match was limited to best-of-three sets. Marshall, playing his second match of the day, defeated Heathcote in straight sets, in front of a diminished crowd, and won the silver prize of seven guineas.[87][88]

Aftermath

On 20 July 1877, the day following the final, a report was published in The Morning Post newspaper:[88]

Lawn Tennis Championship – A fair number of spectators assembled yesterday, notwithstanding the rain, on the beautifully kept ground of the All England Club, Wimbledon, to witness the final contest between Messrs. Spencer Gore and W. Marshall for the championship. The play on both sides was of the highest order and its exhibition afforded a great treat to lovers of the game. All three sets were won buy Mr. Gore, who, therefore, becomes lawn tennis champion for 1877, and wins the £12 12s. gold prize and holds the silver challenge cup, value £25 5s. The second and third prizes were then played for by Messrs. W. Marshall and G.C. Heathcote (best of three sets by agreement). Mr. Marshall won two sets to love, and therefore takes the silver prize (value £12 12s.). Mr. Heathcote takes the third prize, value £3 3s.

A report in The Field stated: "The result was a more easy victory for Mr Spencer Gore than had been expected.".[89] Third-placed Heathcote said that Gore was the best player of the year and had a varied service with a lot of twist on it. Gore, according to Heathcote, was a player with an aptitude for many games and had a long reach and a strong and flexible wrist.[lower-alpha 23] His volleying style was novel at the time, a forceful shot instead of merely a pat back over the net. All the opponents who were defeated by Gore on his way to the title were real tennis players.[58] His victory was therefore regarded as a win of the rackets style of play over the real tennis style, and of the offensive style of the volley player – who comes to the net to force the point, over the baseline player – who plays groundstrokes from the back of the court, intent on keeping the ball in play.[83][91] His volleying game was also successful because the height of the net at the post – 5 ft (1.52 m) in contrast to the modern height of 3 ft 6 in (1.07 m) – made it difficult for his opponents to pass him by driving the ball down the line.[56] Gore indicated that the real tennis players had the tendency to play shots from corner to corner over the middle of the net and did so at such a height that made volleying easy.[92]

Despite his historic championship title, Gore was not enthusiastic about the new sport of lawn tennis. In 1890, thirteen years after winning his championship title, he wrote: "... it is want of variety that will prevent lawn tennis in its present form from taking rank among our great games ... That anyone who has really played well at cricket, tennis, or even rackets, will ever seriously give his attention to lawn tennis, beyond showing himself to be a promising player, is extremely doubtful; for in all probability the monotony of the game as compared with others would choke him off before he had time to excel in it."[32][93] He did return for the 1878 Championship to defend his title in the Challenge Round[lower-alpha 24] but lost in straight sets to Frank Hadow, a coffee planter from Ceylon, who effectively used the lob to counter Gore's net play.[95][96] It was Gore's last appearance at the Wimbledon Championships.[84]

Analysis and rules changes

The tournament generated a profit of £10 and the pony roller stayed in use.[83][97] When the tournament was finished, Henry Jones gathered all the score cards to analyse the results and found that, of the 601 games played during the tournament, 376 were won by the server ("striker-in") and 225 by the receiver ("striker-out").[98] At a time when the service was either made underarm or, usually, at shoulder height, this was seen as a serving dominance and resulted in a modification of the rules for the 1878 Championship.[98] To decrease the target area for the server, the length of the service court was reduced from 26 to 22 ft (7.92 to 6.71 m) and to make passing shots easier against volleyers the height of the net was reduced to 4 ft 9 in (1.45 m) at the posts and 3 feet (0.91 m) at the centre.[40][99] These rules were published jointly by the AEC & LTC and the MCC, giving the AEC & LTC an official rule-making authority and in effect retroactively sanctioning its 1877 rules.[100] It marked the moment when the AEC & LTC effectively usurped the rule-making initiative from the MCC although the latter would still ratify rule changes until 1882.[101][102][lower-alpha 25] In recognition of the importance and popularity of lawn tennis, the club was renamed in 1882 to All England Lawn Tennis Club (AELTC).[65][lower-alpha 26]

Commemorative plaque

On 18 June 2012 a commemorative plaque was unveiled at the former home of the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, in Worple Road, Wimbledon celebrating both the first Wimbledon Championships and the 1908 Olympic tennis event.[lower-alpha 27] The ceremony was performed by Heather Hanbury, Headmistress of Wimbledon High School; Philip Brook, Chairman of the All England Club, and Cr David T Williams JP, Mayor of Merton.[104]

Gentlemen's singles

Final

![]() Spencer Gore defeated

Spencer Gore defeated ![]() William Marshall, 6–1, 6–2, 6–4[79]

William Marshall, 6–1, 6–2, 6–4[79]

- It was Gore's only Grand Slam tournament title.

Second place match

![]() William Marshall defeated

William Marshall defeated ![]() Charles Gilbert Heathcote 6–4, 6–4[83]

Charles Gilbert Heathcote 6–4, 6–4[83]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ According to sports historian Heiner Gillmeister, the game originated in northern France.[2]

- ↑ The first mention of rackets dates to a 1506 memorandum which describes a game of tennis played at Henry VII's Windsor Castle on 7 February 1505 between Philip, King of Castille, and the Marquess of Dorset: "the kynge of Castelle played w the Rackete and gave the marques xv".[5][6]

- ↑ The invention of the lawn mower in 1827 allowed the creation of smooth, flat croquet lawns that could easily be adapted for lawn tennis, and the introduction of vulcanised rubber around 1840 made it possible to create tennis balls that bounced properly on outdoor grass courts.[13][14]

- ↑ The patent application (No.685) was filed on 23 February 1874 and was issued on 24 July 1874. The patent lapsed on 2 March 1877.[16][17]

- ↑ The gentlemen were John H. Walsh, Captain R.F. Dalton, John Hinde Hale, Rev. A. Law, S.H. Clarke Maddock and Walter Jones Whitmore. Walsh, the magazine's editor, was the chairman of the meeting. Whitmore and Maddock were appointed honorary secretary and treasurer respectively.[27]

- ↑ Before the site off Worple Road was discovered and selected, The Crystal Palace at Sydenham, Prince's Club in Knightsbridge, Regent's Park and Holland Park were all approached. They were rejected for various reasons, including costs.[29]

- ↑ The announcement of the meeting was made in The Field of 20 February 1875: "A meeting will be held at the Pavilion, Lord's Ground on Wednesday next, a two o'clock, by the kind permission of the Marylebone Club for the purpose of eliciting the opinions of all who are interested in the game of lawn tennis".[36]

- ↑ The members of the MCC Tennis Committee were Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, J.M. Heathcote, E. Chandos Leigh, W.H. Dyke and C.G. Lyttelton.[38]

- ↑ The Gentlemen's Singles was the only event held at the Wimbledon Championships until 1884, when the Ladies' Singles and Men's Doubles events were introduced. The Ladies' Doubles and Mixed Doubles events were added in 1913. The Irish Championships in 1879 was the first tournament to feature a Ladies' Singles event.

- ↑ There is a record of a tournament held in August 1876 on the courts of William Appleton in Nahant, United States, but since this was an informal, private event it is not recognised as an official tournament.[46]

- ↑ The three other Grand Slam tournaments were founded in 1881 (U.S. National Championships), 1891/1925 (French Championships), and 1905 (Australasian Championships). The Wimbledon Championships were designated as an official World Grass Court Championship by the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF) in 1913, together with the World Hard Court Championships and World Covered Court Championships. This lasted until 1923, when it became an 'Official Championship' (together with the championships of France, USA and Australia) to allow the USA, whose championship was also played on grass, to join the ILTF.[48] The term Grand Slam was not an official designation and was first used by the press in 1933.

- ↑ The term "amateur" as used here has a specific meaning that differs from its current connotation. The distinction between "amateurs" and "professionals" at the time was not so much one of remuneration but more one of social status and class. The "amateur" was a gentleman who was of independent means and belonged to the upper or middle class, whereas "professionals" invariably came from the working class.[53] The construct "Gentleman Amateur" was a method of social distinction and the amateur code was frequently a means of excluding working-class players from competition. The phrase "open to all amateurs" was thus a means to ensure that only people with the desired background would participate in the tournament.[54][55]

- ↑ The original Field Cup was handed out to the winner of the gentlemen's singles event until 1883 when it came in permanent possession of William Renshaw after he had won the cup for the third successive time. After three further successive title wins Renshaw also became the owner of the replacement cup worth 50 guineas. In response the Club purchased a new Challenge Cup in 1887 at a cost of 100 guineas which remains in its possession. The original Field Cup is now on display in the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum.[59][60]

- ↑ According to Tingay (1977) there were in fact only twelve courts. It is not known how many courts were used but five would have been sufficient.[62] The courts were laid out in a grid of three rows of four courts.[63]

- ↑ According to Gillmeister (1998) it was not Charles Gilbert but his brother John Moyer Heathcote who, as a representative of the MCC, was part of the rules sub-committee.[65]

- ↑ This was in contrast to the 1875 MCC regulations which prescribed the rackets method of scoring in which only the serving side ("hand-in") could score and each game consisted of 15 aces (points). This method was also previously adopted by Major Clopton Wingfield's Sphairistikè, Harry Gem's & Augurio Perera's Pelota and John Hale's Germains Lawn Tennis.

- ↑ The original lawn tennis balls were uncovered. In a letter to The Field published on 5 December 1874, John Heathcote stated that he had experimented with tennis balls covered with white flannel and found that they bounced better and were easier to see and control.[70][71]

- ↑ The programme was printed on a thin card folded into two (6 x 4 inches after folding). The front page had the title 'All England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club' as well as a date and the price. The inside showed the full draw with a list of the prizes and the back page showed the layout of the twelve courts in relation to the pavilion.[63]

- ↑ In the first years of the championship byes could be distributed through the entire draw. Only from 1885 onward were byes used exclusively in the first round. This was formalised in the Bagnall–Wild system which came into effect in 1887.[76][77]

- ↑ A 'dead' court refers to a tennis court where the ball bounces significantly less compared to other courts or to the same court under different weather conditions.

- ↑ A Centre Court did not exist during the first four years of the championship, and the match was in all likelihood played on Court 1 in front of the pavilion.[58][81]

- ↑ Writing in 1957, tennis author and former player Tony Mottram said of Gore using the volley: "He was immediately branded unsporting and unscrupulous."[85]

- ↑ In a chapter on lawn tennis which Heathcote wrote for The Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes in 1890, he stated "Mr. Gore was much the best player of the year. He was gifted with a natural genius for all games, great activity, a long reach, and a strong and flexible wrist. (...) He was the first to realize (...) the necessity of forcing his opponent to the back line, when he would approach the net (...) Though the hard over-hand service was not then invented (...) his service was more varied than that of almost all other players, and his under-hand service in particular was characterized by an extraordinary power of twist."[90]

- ↑ The Challenge Round system was introduced at Wimbledon in 1878. The existing champion, in this case Spencer Gore, did not have to play through the tournament but instead faced the winner of the All Comers' tournament in a Challenge Round match to determine the new champion. This system was abolished in 1922.[94]

- ↑ The AELTC's legislative authority was passed on in 1889 to the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA), formed in 1888, who in turn handed it over to the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF) in 1922.

- ↑ In 1899 the name of the club was changed again to All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club and that has remained its name to the present day.[103]

- ↑ In 1922 the Club moved to its current location at Church Road. The site of the inaugural tournament at Worple Road now serves as a playing field for the Wimbledon High School.[104]

References

- 1 2 "Wimbledon draws archive – 1877 Gentlemen's singles". AELTC. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), pp. 15,106,117

- ↑ Clerici, Gianni (1976). Tennis. London: Octopus Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7064-0523-1. OCLC 16360735.

- ↑ Robertson (1974), p. 14

- ↑ Marshall (1878), p. 62

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 103

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), pp. 27,28

- ↑ Parmly Paret, J. (1904). Lawn Tennis, its Past, Present, and Future (PDF). The American Sportsman's Library. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 4, 5. OCLC 2068608. OL 6946876M.

- ↑ Marshall (1878), p. 97

- ↑ Birley (1993), p. 312

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 174

- 1 2 John Barrett (22 June 2014). "Wimbledon 2014: How SW19 gave a country garden game to the world". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- 1 2 Sally Mitchell, ed. (2011). Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia. Garland reference library of social science. 438. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 791. ISBN 978-0-415-66851-4.

- 1 2 Dave Scheiber (1 July 1986). "A tennis tapestry". St. Petersburg Times. p. 3C.

- ↑ Baker, William J. (1988). Sports in the Western world (Rev. ed., Illini books ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-252-06042-7.

- ↑ Alexander (1974), p. 15

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 185

- ↑ Barrett (2010), pp. 44–50

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 16

- 1 2 Gary Morley (22 June 2011). "125 years of Wimbledon: From birth of lawn tennis to modern marvels". CNN. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Barrett (2003), p. 25

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 14

- ↑ Robertson (1974), p. 22

- ↑ Wingfield, Walter (2008) [1874]. The Game of Sphairistike or Lawn Tennis (Facsimile of 1874 ed.). Surrey: Wimbledon Society Museum Press. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-1-904332-81-7.

- ↑ Collins (2010), p. 6

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 20

- ↑ Tingay (1977), p. 14

- ↑ Barrett (2003), p. 8

- 1 2 Tingay, Lance (1977). Tennis, A Pictorial History (New and revised ed.). Glasgow: William Collins Sons & Co. pp. 26, 30, 31. ISBN 0-00-434553-3.

- 1 2 Parsons (2006), p. 11

- 1 2 3 Tingay (1977), p. 16

- 1 2 Schickel, Richard (1975). The World of Tennis. New York: Random House. p. 40. ISBN 0-394-49940-9.

- ↑ Haylett, John; Evans, Richard (1989). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Tennis. London: Marshall Cavendish. p. 14. ISBN 0-86307-897-4.

- 1 2 3 Barrett (2001), p. 1

- ↑ Robertson (1974), p. 23

- ↑ Alexander (1974), p. 32

- ↑ Barrett (2003), pp. 29,30

- ↑ Alexander (1974), p. 33

- ↑ Somerset (1894), pp. 133,134

- 1 2 Frances E. Slaughter, ed. (1898). The Sportswoman's Library (PDF). II. Westminster: Archibald Constable & Co. pp. 314, 315. OCLC 2230880.

- ↑ "Laws of Lawn Tennis – Revised by the M.C.C.". Baily's Magazine of Sports and Pastimes. Cornhill: A.H. Baily & Co. XXVII (185): 138–140. July 1885. OCLC 12030733.

- ↑ Barrett (2003), p. 30

- ↑ Alexander (1974), pp. 77–107

- ↑ Todd (1979), p. 76

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 31

- ↑ Grasso, John (2011). Historical Dictionary of Tennis. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. pp. XV, 91. ISBN 978-0-8108-7237-0.

- ↑ Robertson, Max (1987). Wimbledon : Centre Court of the Game : Final Verdict (3rd ed.). London: British Broadcasting Corporation. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-563-20454-1.

- ↑ "Lawn Tennis – No "World" Title". Western Daily Press. British Newspaper Archive. 6 March 1923. p. 8. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Todd (1979), pp. 94–95

- ↑ Todd (1979), p. 94

- ↑ Parsons (2006), p. 50

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 13

- ↑ Birley, Derek (2004). A Social History of English Cricket (1. publ., repr. ed.). London: Aurum Press. pp. 105–107. ISBN 978-1-85410-941-5.

- ↑ Holt, Richard (1990). Sport and the British : A Modern History (Clarendon pbk. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 98–116. ISBN 978-0-19-285229-8.

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 194

- 1 2 Peter Schwed (1972). Allison Danzig, ed. The Fireside Book of Tennis. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 493, 494. ISBN 978-0-671-21128-8.

- 1 2 Rowley (1986), p. 10

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Todd (1979), p. 95

- ↑ Sarah Edworthy (23 June 2014). "Wimbledon in 13 objects: 1. The Field Cup". www.wimbledon.com. AELTC. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Little (2013), pp. 296–297

- ↑ Little (2013), p. 296

- 1 2 3 4 Tingay (1977), p. 17

- 1 2 Little (2013), p. 345

- ↑ Parsons (2006), p. 12

- 1 2 3 Gillmeister (1998), p. 188

- ↑ Barrett (2001), pp. 32,33

- ↑ Todd (1979), p. 78

- ↑ Brigadier J.G. Smyth (1953). Lawn Tennis. British Sports: Past & Present. London: B.T. Badsford Ltd. p. 21. OCLC 1142926. OL 6144675M.

- ↑ "Rackets and Strings – History". ITF. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), pp. 188,352

- ↑ "A Tennis Balls Controversy". The Spectator. 27 February 1926. pp. 361, 362.

- ↑ Little (2013), pp. 54–55

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), pp. 193,194

- 1 2 "Lawn Tennis Championship". The Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 11 July 1877. p. 6. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Lawn Tennis Championship". The Morning Post. British Newspaper Archive. 12 July 1877. p. 7. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Joseph T. Whittelsey (ed.). Wright & Ditson's Lawn Tennis Guide for 1893 (PDF). Boston: Wright & Ditson. pp. 124, 125. OCLC 32300203.

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 355

- ↑ "Lawn Tennis Championship". The Standard. British Newspaper Archive. 13 July 1877. p. 6. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Atkin, Ron. "1877 Wimbledon Championships". www.wimbledon.com. AELTC. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Ronald Atkin (20 June 1999). "Wimbledon '99: When Wimbledon was Worpledon". The Independent.

- ↑ Little (2013), p. 148

- ↑ "Lawn Tennis Championship". The Standard. British Newspaper Archive. 20 July 1877. p. 6. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Tingay (1977), p. 20

- 1 2 3 John Barrett, Alan Little (2012). Wimbledon Gentlemen's Singles Champions 1877–2011. Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum. pp. 1, 2. ISBN 978-0-906741-51-1.

- ↑ Tony Mottram (9 January 1957). "Tennis "Revolt"". The Age.

- ↑ Baltzell, E. Digby (1995). Sporting Gentlemen: Men's Tennis from the Age of Honor to the Cult of the Superstar. New York [u.a.]: Free Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-02-901315-1.

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 24

- 1 2 "Spencer Gore – Gentlemen's Singles Champion at Wimbledon in 1877". The British Newspaper Archive. 27 June 2012.

- ↑ Rowley (1986), p. 12

- ↑ Somerset (1894), pp. 143,144

- ↑ Oliver S. Campbell (1893). The Game of Lawn Tennis and how to play it (PDF). New York: American Sports Publishing Company. p. 17.

- ↑ Somerset (1894), p. 283

- ↑ Barrett (2001), pp. 25,26

- ↑ Maurice Brady, ed. (1958). The Encyclopedia of Lawn Tennis. London: Robert Hale Limited. p. 30.

- ↑ "Wimbledon Draws Archive – 1878 Gentlemen's Singles". AELTC. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Gillmeister (1998), p. 195

- ↑ Little (2013), p. 542

- 1 2 Tingay (1977), p. 21

- ↑ Alexander (1974), p. 36

- ↑ Eric Dunning, ed. (2006). Sport Histories : Figurational Studies in the Development of Modern Sports. London: Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-415-39794-0.

- ↑ Wallis Myers, A. (1908). The Complete Lawn Tennis Player (PDF). Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs & Co. pp. 4, 8. OCLC 9035307. OL 7005977M.

- ↑ Somerset (1894), p. 146

- ↑ Barrett (2001), p. 2

- 1 2 "Tennis History Celebrated in Another Corner of SW19". AELTC. 18 June 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

Sources

- Alexander, George E. (1974). Lawn Tennis : Its Founders & Its Early Days. Lynn: H.O. Zimman. OCLC 1177585.

- Barrett, John (2001). Wimbledon : The Official History of the Championships. London: CollinsWillow. ISBN 0-00-711707-8.

- Barrett, John (2003). Wimbledon – Serving Through Time. London: Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum. ISBN 978-0-906741-32-0.

- Barrett, John (2010). The Original Rules of Tennis. Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN 978-1-85124-318-1.

- Birley, Derek (1993). Sport and the Making of Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3759-7.

- Collins, Bud (2010). The Bud Collins History of Tennis : An Authoritative Encyclopedia and Record Book (2nd ed.). [New York]: New Chapter Press. ISBN 978-0-942257-70-0.

- Gillmeister, Heiner (1998). Tennis : A Cultural History (Repr. ed.). London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-0195-2.

- Little, Alan (2013). 2013 Wimbledon Compendium (23rd ed.). London: The All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club. ISBN 978-1-899039-40-1.

- Marshall, Julian (1878). The Annals of Tennis. London: "The Field" Office. OCLC 12577084.

- Parsons, John (2006). The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Tennis : The Definitive Illustrated Guide to World Tennis (Rev. ed.). London: Carlton. ISBN 978-1-84442-157-2.

- Robertson, Max (1974). The Encyclopedia of Tennis : 100 Years of Great Players and Events. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-796042-0.

- Rowley, [compiled by] Malcolm (1986). Wimbledon : 100 Years of Men's Singles. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-99223-9. OCLC 15658165.

- Somerset, Henry, ed. (1894). Tennis, Lawn Tennis, Rackets, Fives. Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes (3 ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. OCLC 558974625. OL 6939991M.

- Tingay, Lance (1977). 100 Years of Wimbledon. Enfield [Eng.]: Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 0-900424-71-0. OCLC 607858270.

- Todd, Tom (1979). The Tennis Players : from Pagan Rites to Strawberries and Cream. Guernsey: Vallency Press. OCLC 6041549.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1877 Wimbledon Championship. |

| Preceded by None |

Grand Slams | Succeeded by 1878 Wimbledon |