Fall of Suharto

Suharto resigned as president of Indonesia in May 1998 following the collapse of support for his three-decade long presidency. The resignation followed severe economic and political crises in the previous 6 to 12 months. B.J. Habibie continued at least a year of his remaining presidential years, followed by Abdurrahman Wahid in 1999.

Dissent under the New Order

Coming to power in 1966 on the heels of an alleged coup by the Indonesian Communist Party, the government of the former general Suharto adopted policies that severely restricted civil liberties and instituted a system of rule that effectively split power between his own Golkar Party and the military.

In 1970, corruption prompted student protests and an investigation by a government commission. Suharto responded by banning student protest, forcing the activists underground. Only token prosecution of cases recommended by the commission was pursued. The pattern of co-opting a few of his more powerful opponents while criminalizing the rest became a hallmark of Suharto's rule.

In order to maintain a veneer of democracy, Suharto made a number of electoral reforms. He stood for election before electoral college votes every five years, beginning in 1973. According to his electoral rules, however, only three parties were allowed to participate in the election: his own Golkar party; the Islamist United Development Party (PPP), and the Democratic Party of Indonesia (PDI). All the previously existing political parties were forced to be part of either the PPP and PDI, with public servants under pressure to join the membership of Golkar. In a political compromise with the powerful military, he banned its members from voting in elections, but set aside 100 seats in the electoral college for their representatives. As a result, he won every election in which he stood, in 1978, 1983, 1988, 1993, and 1998.

This authoritarianism became an issue in the 1980s. On 5 May 1980 a group Petition of Fifty (Petisi 50) demanded greater political freedoms. It was composed of former military men, politicians, academics and students. The Indonesian media suppressed the news and the government placed restrictions on the signatories. After the group's 1984 accusation that Suharto was creating a one-party state, some of its leaders were jailed.

In the same decade, it is believed by many scholars that the Indonesian military split between a nationalist "red and white faction" and an Islamist "green faction." As the 1980s closed, Suharto is said to have been forced to shift his alliances from the former to the latter, leading to the rise of Jusuf Habibie in the 1990s.

After the 1990s brought end of the Cold War, Western concern over communism waned, and Suharto's human rights record came under greater international scrutiny. In 1991, the murder of East Timorese civilians in a Dili cemetery, also known as the "Santa Cruz Massacre", caused American attention to focus on its military relations with the Suharto regime and the question of Indonesia's occupation of East Timor. In 1992, this attention resulted in the Congress of the United States passing limitations on IMET assistance to the Indonesian military, over the objections of President George H.W. Bush. In 1993, under President Bill Clinton, the U.S. delegation to the UN Human Rights Commission helped pass a resolution expressing deep concern over Indonesian human rights violations in East Timor.

Cracks emerge

In 1996, the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI), a legal party that had been used by the New Order as a benign prop for the New Order’s electoral system, began to assert its independence, under Megawati Sukarnoputri, the daughter of the popular father of the nation, Sukarno. In response, Suharto attempted to foster a split over the leadership of PDI, backing a co-opted faction loyal to deputy speaker of Parliament Suryadi against supporters of "Mega".

After the Suryadi faction announced a party congress to sack Megawati would be held in Medan 20–22 June, Megawati proclaimed that her supporters would hold demonstrations in protest. The Suryadi faction went through with its sacking of Megawati, and the demonstrations manifested themselves throughout Indonesia. This led to several confrontations on the streets between protesters and security forces, and recriminations over the violence. The protests culminated in the military allowing Megawati's supporters to take over PDI headquarters in Jakarta, with a pledge of no further demonstrations.

Suharto allowed the occupation of PDI headquarters to go on for almost a month, as attentions were also on Jakarta due to a set of high-profile ASEAN meetings scheduled to take place there. Capitalizing on this, Megawati supporters organized "democracy forums" with several speakers at the site. On 26 July, officers of the military, Suryadi, and Suharto openly aired their disgust with the forums.[1]

On 27 July, police, soldiers, and persons claiming to be Suryadi supporters stormed the headquarters. Several Megawati supporters were killed, and over two-hundred were arrested and tried under the Anti-Subversion and Hate-spreading laws. The day would become known as "Black Saturday" and mark the beginning of a renewed crackdown by the New Order government against supporters of democracy, now called the "Reformasi" or Reformation.[2]

The political tensions in Jakarta were accompanied by anti-Chinese riots in Situbondo (1996), Tasikmalaya (1996), Banjarmasin (1997), and Makassar (1997); while violent ethnic clashes broke out between the Dayak and Madurese settlers in Central Kalimantan in 1997. After a violent campaign season, Golkar won the rigged May 1997 MPR elections. The new MPR voted unanimously to re-elect Suharto to another five-year term in office on March 1998, upon which he appointed his protégé BJ Habibie as vice-president while stacking the cabinet with his own family and business associates (his daughter Tutut became Minister of Social Affairs). The Government's increase of fuel prices by 70% in May triggered rioting in Medan. With Suharto increasingly seen as the source of the country's mounting economic and political crises, prominent political figures, including Muslim politician Amien Rais, spoke out against his presidency, and on January 1998 university students began organising nationwide demonstrations.[3]

Monetary crisis

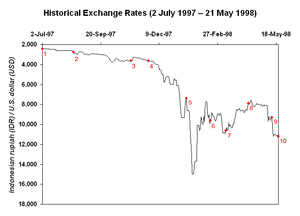

In the second half of 1997, Indonesia became the country hardest hit by the Asian economic crisis. The economy suffered a flight of foreign capital leading to the Rupiah falling from Rp 2,600 per dollar in August 1997 to over Rp 14,800 per dollar by January 1998. Those Indonesian companies with US dollar-denominated borrowings struggled to service these debts with their Rupiah earnings and many went bankrupt. Efforts by Bank Indonesia to defend its managed float regime by selling US dollars had little effect on the currency's decline, but instead drained Indonesia's foreign exchange reserves.[5]

Weaknesses in the Indonesian economy, including high levels of debt, poor financial management systems and crony capitalism, were identified as underlying causes. Volatility in the global financial system and over-liberalisation of international capital markets were also cited.[6] The government responded by floating the currency, requesting International Monetary Fund assistance, closing some banks and postponing major capital projects.

In December 1997, Suharto for the first time did not attend an ASEAN presidents' summit, which was later revealed to be due to a minor stroke, creating speculation about his health and the immediate future of his presidency. In mid December as the crisis swept through Indonesia and an estimated $150 bn of capital was being withdrawn from the country, he appeared at a press conference to assure he was in charge and to urge people to trust the government and the collapsing Rupiah.[7]

Suharto's attempts to re-instill confidence, such as ordering generals to personally reassure shoppers at markets and an "I Love the Rupiah" campaign, had little effect. Evidence suggested that Suharto's family and associates were being spared the toughest requirements of the IMF reform process, and there was open conflict between economic technocrats implementing IMF plans and Suharto-related vested interests, further undermining confidence in the economy.[8] The government's unrealistic 1998 budget and Suharto's announcement of Habibie as the next vice president both caused further currency instability.[9] Suharto reluctantly agreed to a wider reaching IMF package of structural reforms in January 1998 in exchange for $43 billion in liquidity (with a third letter of intent with the IMF being signed in April of that year).[9] However, the Rupiah dropped to a sixth of its pre-crisis value, and rumours and panic led to a run on stores and pushed up prices.[10]

In January 1998, the government was forced to provide emergency liquidity assistance (BLBI), issue blanket guarantees for bank deposits, and set up the Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency to take over management of troubled banks in order to prevent the collapse of the financial system. Based on IMF recommendations, the government increased interest rates to 70% pa on February 1998 to control high inflation caused by the higher prices of imports. However, this action restricted the availability of credit to the corporate sector.[11][12]

Suharto's position as president had remained solid for 30 years so long as the Indonesia economy grew strongly. When the economic crisis hit in 1997/98, Suharto's performance legitimacy disappeared and his once strong support disappeared both domestically and internationally.[13]

Political

As the financial crisis unfolded, opposition leaders such as Amien Rais became more vocal in their criticism of Suharto and the New Order. There were rumours of splits in the armed forces, imminent riots and talk of a bloody crackdown.[14]

Demonstrations and riots

In 1997 and 1998 there were riots in various parts of Indonesia. Sometimes these riots were aimed against the Chinese-Indonesians. Some riots looked spontaneous and some looked as if they had been planned. One theory was that pro-Suharto generals were trying to weaken the forces of democracy by increasing the divisions between the orthodox and the non-orthodox Muslims, between the Muslims and the Christians and between the Chinese and the non-Chinese. Another theory was that certain generals were trying to topple Suharto.[15]

Human Rights Watch Asia reported that in the first five weeks of 1998 there were over two dozen demonstrations, price riots, bomb threats, and bombings on Java and that unrest was spreading to other islands.[9]

The Trisakti incident

At the start of May 1998, students were holding peaceful demonstrations on university campuses across the country. They were protesting against massive price rises for fuel and energy, and they were demanding that President Suharto should step down.

On 12 May, students at Jakarta's Trisakti University, many of them the children of the elite, planned to march to Parliament to present their demands for reform. The police prevented the students from marching, and a little after 5 pm, uniformed men on motorcycles appeared on the flyover overlooking Trisakti. Shots rang out, killing four students, while at Semanggi nine students were killed, followed by four more the next year.[16]

Riots of 13–14 May

On 13 and 14 May rioting across Jakarta destroyed many commercial centres and over 1,000 died. Ethnic Chinese were targeted.[14] The riots were allegedly instigated by Indonesian military members who were out of uniform. Homes were attacked and women were raped by gangs of men who wore ordinary clothing. The US State Department and many human rights groups have argued that the Indonesian military and police participated and incited the rioting and violence against Sino-Indonesians.[17] However, most of the deaths suffered when Chinese owned supermarkets in Jakarta were targeted for looting from 13–15 May were not Chinese, but the Javanese Indonesian looters themselves, who were burnt to death by the hundreds when a fire broke out.[18][19][20][21][22]

Over 1,000 and as many as 5,000 people died during these riots in Jakarta and other cities such as Surakarta. Many victims died in burning malls and supermarkets but some were shot or beaten to death. A government minister reported the damage or destruction of 2,479 shop-houses, 1,026 ordinary houses, 1,604 shops, 383 private offices, 65 bank offices, 45 workshops, 40 shopping malls, 13 markets, and 12 hotels.

Alleged involvement of the military in planning the riots

Father Sandyawan Sumardi, a 40-year-old Jesuit priest and son of a police chief, led an independent investigation into the events of May 1998. As a member of the Team of Volunteers for Humanitarian Causes he interviewed people who had witnessed the alleged involvement of the military in organizing the riots and rapes.

A security officer alleged that Kopassus (special forces) officers had ordered the burning down of a bank; a taxi driver reported hearing a man in a military helicopter encouraging people on the ground to carry out looting; shop-owners at a Plaza claimed that, before the riots, military officers tried to extract protection money; a teenager claimed he and thousands of others had been trained as protesters; a street child alleged that Kopassus officers ordered him and his friends to become rioters; there was a report of soldiers being dressed up as students and then taking part in rioting; eyewitnesses spoke of muscular men with short haircuts arriving in military-style trucks and directing attacks on Chinese homes and businesses.

In May 1998, thousands of Indonesian citizens were murdered and raped... ¶ The Joint Fact Finding Team established to inquire into the 1998 massacres found that there were serious and systematic human rights violations throughout Jakarta. The Team also found that rioters were encouraged by the absence of security forces, and that the military had played a role in the violence. The Team identified particular officials who should be held to account.¶ The Special Rapporteur on violence against women... also pointed to evidence suggesting that the riots had been organized (E/CN.4/1999/68/Add.3, para. 45).[23]

Banyuwangi riots in East Java

A witchhunt in Banyuwangi against alleged sorcerers spiraled into widepsread riots and violence. In addition to alleged sorcerers, Islamic clerics were also targeted and killed, and Nahdlatul Ulama members were murdered by rioters.[24][25]

Anti-Madurese violence

In West Kalimantan there was communal violence between Dayaks and Madurese in 1996, in the Sambas riots in 1999 and the Sampit conflict 2001, resulting in large-scale massacres of Madurese.[26][27][28] In the Sambas conflict, both Malays and Dayaks massacred Madurese.

Resignation of Suharto

Reportedly the military was split. There was said to be a power struggle between Prabowo and Wiranto. Both generals claimed to be loyal to Suharto. Some feared factionalism could lead to a civil war.

Some of Suharto's former allies deserted him. Wiranto allowed students to occupy Parliament. Wiranto reported to Suharto on 20 May that Suharto no longer had the support of the army.

Suharto was forced to resign on 21 May and was replaced by Habibie, his Vice President.

In 1998 one of the key generals was Prabowo, son of former Finance Minister Dr. Sumitro Djojohadikusumo who may have once worked with the British and the Americans against Sukarno. Prabowo had learned about terrorism at Fort Bragg and Fort Benning in the US. In May 1998, Prabowo was commander of Kostrad, the strategic reserve, the regiment Suharto commanded when he took power in 1965. Prabowo's friend Muchdi ran Kopassus (special forces) and his friend Sjafrie ran the Jakarta Area Command. General Wiranto, the overall head of the military, was seen as a rival to Prabowo.

Allegedly, late on the evening on 21 May, Prabowo arrived at the presidential palace and demanded that he be made chief of the armed forces. Reportedly, Habibie escaped from the palace. On 22 May, Prabowo was sacked as head of Kostrad. Wiranto remained as chief of the armed forces. Wiranto's troops began removing the students from the parliament building.[29]

Continued military influence

One result of the May riots was that the military appeared to remain the power behind the throne. During a time of widespread fear, the military could claim to offer stability, though it was they who had perhaps helped to orchestrate the disorder. In 2004, General Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was elected president. Each of the three presidential tickets in 2009 included a general as candidate for either president or vice president.

The aftermath

Not so often reported was the silent departure of families and wealth from the country. The emigrants were not exclusively of Chinese descent, but also included wealthy natives or pribumis and Suharto’s cronies. The immediate destination was Singapore, where some stayed permanently while others moved on to Australia, the US and Canada. Many of these families returned when the political situation stabilized a few years later.

Since the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime, a variety of state-sponsored initiatives have been implemented to address mass violations of human rights. In these efforts, research shows that senior government officials consistently failed to achieve truth, accountability, institutional reform and reparations for the most serious crimes.[30]

Notes

- ↑ Aspinall 1996

- ↑ Amnesty International 1996

- ↑ Elson (2001), p.267

- ↑ "Indonesia Floats the Rupiah, And It Drops More Than 6%". The New York Times. 15 August 1997. p. D6. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2001/wp0152.pdf

- ↑ Monash Asia Institute (1999), p. 1

- ↑ Friend (2003), p. 313.

- ↑ Monash Asia Institute (1999), p. v.

- 1 2 3 Friend (2003), p. 314.

- ↑ Friend (2003), p. 314; Monash Asia Institute (1999), p. v

- ↑ McDonald, Hamish (28 January 2008). "No End to Ambition". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ Vickers (2005), pp. 203–207.

- ↑ Monash Asia Institute (1999), p. 1.

- 1 2 Monash Asia Institute (1999), p. viii

- ↑ Tinder-box or conspiracy?

- ↑ reliefweb.int

- ↑ fas.org

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20000920073842/http://www.serve.com/inside/digest/dig86.htm

- ↑ http://www.library.ohiou.edu/indopubs/1998/05/31/0029.html

- ↑ "Over 1,000 killed in Indonesia riots: rights body Reuters - June 3, 1998 Jim Della-Giacoma, Jakarta", "The May riots DIGEST No.61 - May 29, 1998"

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=bCsgAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA34#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Collins 2002, p. 597.

- ↑ http://www.ahrchk.net/statements/mainfile.php/2003statement/87/ "INDONESIA: Five years after May 1998 rights, those responsible for the atrocities remain at large," Asian Human Rights Commission statement 7 April 2003

- ↑ http://www.insideindonesia.org/weekly-articles/the-banyuwangi-murders

- ↑ http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2053925,00.html

- ↑ Armed Conflicts Report. Indonesia - Kalimantan

- ↑ Dayak

- ↑ THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DAYAK AND MADURA IN RETOK by Yohanes Supriyadi

- ↑ Colmey, John (24 Jun 2001). "Indonesia". Time Magazine. Time, Inc. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ↑ "Derailed: Transitional Justice in Indonesia since the fall of Soeharto", International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ)

See also

- Jakarta Riots of May 1998

- Prabowo Subianto

- Wiranto

- Arab Spring

- People Power Revolution

- Maluku sectarian conflict

- 2000 Walisongo school massacre

References

- Friend, Theodore (2003). Indonesian Destinies. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01834-6.

Further reading

- Chandra, Siddharth and Douglas Kammen. (2002). "Generating Reforms and Reforming Generations: Military Politics in Indonesia’s Transition to Democracy." World Politics, Vol. 55, No. 1.

- Dijk, Kees van. 2001. A country in despair. Indonesia between 1997 and 2000. KITLV Press, Leiden, ISBN 90-6718-160-9

- Kammen, Douglas and Siddharth Chandra (1999). A Tour of Duty: Changing Patterns of Military Politics in Indonesia in the 1990s. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project Publication No. 75.

- Pepinsky, Thomas B. (2009). Economic Crises and the Breakdown of Authoritarian Regimes: Indonesia and Malaysia in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-76793-4