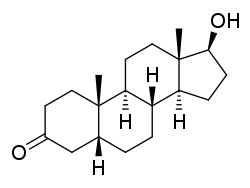

5β-Dihydrotestosterone

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(5R,8R,9S,10S,13S,14S,17S)-17-Hydroxy-10,13-dimethyl-1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-tetradecahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthren-3-one | |

| Other names

5β-Androstan-17β-ol-3-one; Etiocholan-17β-ol-3-one; 5β-Dihydrotestosterone; 5β-DHT | |

| Identifiers | |

| 571-22-2 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:2150 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL373357 |

| ChemSpider | 10827 |

| PubChem | 11302 |

| |

| Properties | |

| C19H30O2 | |

| Molar mass | 290.45 g·mol−1 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

5β-Dihydrotestosterone (5β-DHT), also known as 5β-androstan-17β-ol-3-one or as etiocholan-17β-ol-3-one, is an etiocholane (5β-androstane) steroid as well as an inactive metabolite of testosterone formed by 5β-reductase in the liver and bone marrow[1][2] and an intermediate in the formation of 3α,5β-androstanediol and 3β,5β-androstanediol (by 3α- and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase) and, from them, respectively, etiocholanolone and epietiocholanolone (by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase).[3][4] Unlike its isomer 5α-dihydrotestosterone (5α-DHT or simply DHT), 5β-DHT either does not bind to or binds only very weakly to the androgen receptor.[1] 5β-DHT is notable among metabolites of testosterone in that, due to the fusion of the A and B rings in the cis orientation, it has an extremely angular molecular shape, and this could be related to its lack of androgenic activity.[5] 5β-DHT, unlike 5α-DHT, is also inactive in terms of neurosteroid activity,[6][7] although its metabolite, etiocholanolone, does possess such activity.[8][9]

See also

References

- 1 2 Hormones, Brain and Behavior Online. Academic Press. 18 June 2002. pp. 2262–. ISBN 978-0-08-088783-8.

- ↑ H.-J. Bandmann; R. Breit; E. Perwein (6 December 2012). Klinefelter’s Syndrome. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-3-642-69644-2.

- ↑ Shlomo Melmed; Kenneth S. Polonsky; P. Reed Larsen; Henry M. Kronenberg (30 November 2015). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 711–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7.

- ↑ Anita H. Payne; Matthew P. Hardy (28 October 2007). The Leydig Cell in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-1-59745-453-7.

- ↑ B.A. Cooke; H.J. Van Der Molen; R.J.B. King (1 November 1988). Hormones and their Actions. Elsevier. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-0-08-086077-0.

- ↑ Current Topics in Membranes and Transport. Academic Press. 1 February 1988. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-0-08-058502-4.

- ↑ Abraham Weizman (1 February 2008). Neuroactive Steroids in Brain Function, Behavior and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Novel Strategies for Research and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-1-4020-6854-6.

- ↑ Li P, Bracamontes J, Katona BW, Covey DF, Steinbach JH, Akk G (June 2007). "Natural and enantiomeric etiocholanolone interact with distinct sites on the rat alpha1beta2gamma2L GABAA receptor". Mol. Pharmacol. 71 (6): 1582–90. doi:10.1124/mol.106.033407. PMID 17341652.

- ↑ Kaminski RM, Marini H, Kim WJ, Rogawski MA (June 2005). "Anticonvulsant activity of androsterone and etiocholanolone". Epilepsia. 46 (6): 819–27. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00705.x. PMC 1181535

. PMID 15946323.

. PMID 15946323.