51 Pegasi

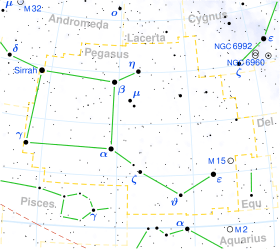

51 Pegasi (abbreviated 51 Peg), also named Helvetios,[10] is a Sun-like star located 50.9 light-years (15.6 parsecs)[1] from Earth in the constellation of Pegasus. It was the first main-sequence star found to have an exoplanet (designated 51 Pegasi b, unofficially dubbed Bellerophon, later named Dimidium) orbiting it.[11]

Properties

The star is of apparent magnitude 5.49, and so is visible with the naked eye under suitable viewing conditions.

51 Pegasi has a stellar classification of G5V,[3] indicating that it is a main-sequence star that is generating energy through the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen at its core. The effective temperature of the chromosphere is about 5571 K, giving 51 Pegasi the characteristic yellow hue of a G-type star.[12] It is estimated to be 6.1–8.1 billion years old, somewhat older than the Sun, with a radius 24% larger and 11% more massive. The star has a higher proportion of elements other than hydrogen/helium compared to the Sun; a quantity astronomers term a star's metallicity. Stars with higher metallicity such as this are more likely to host planets.[3] In 1996 astronomers Baliunas, Sokoloff, and Soon measured a rotational period of 37 days for 51 Pegasi.[13]

Although the star was suspected of being variable during a 1981 study,[14] subsequent observation showed there was almost no chromospheric activity between 1977 and 1989. Further examination between 1994 and 2007 showed a similar low or flat level of activity. This, along with its relatively low X-ray emission, suggests that the star may be in a Maunder minimum period[3] during which a star produces a reduced number of star spots.

The star rotates at an inclination of 79+11

−30 degrees relative to Earth.[7]

Nomenclature

51 Pegasi is the Flamsteed designation. On its discovery, the planet was designated 51 Pegasi b by its discoverers and unofficially dubbed Bellerophon by the astronomer Geoffrey Marcy, in keeping with the convention of naming planets after Greek and Roman mythological figures (Bellerophon was a figure from Greek mythology who rode the winged horse Pegasus).[15]

In July 2014 the International Astronomical Union launched a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[16] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[17] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning names were Helvetios for this star and Dimidium for its planet.[18]

The winning names were those submitted by the Astronomische Gesellschaft Luzern, Switzerland. 'Helvetios' is Latin for 'the Helvetian' and refers to the Celtic tribe that lived in Switzerland during antiquity; 'Dimidium' is Latin for 'half', referring to the planet's mass of at least half the mass of Jupiter.[19]

In 2016, the IAU organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[20] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. In its first bulletin of July 2016,[21] the WGSN explicitly recognized the names of exoplanets and their host stars approved by the Executive Committee Working Group Public Naming of Planets and Planetary Satellites, including the names of stars adopted during the 2015 NameExoWorlds campaign. This star is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[10]

Planetary system

On October 6, 1995, Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting 51 Pegasi.[11] The discovery was made with the radial velocity method on a telescope at Observatoire de Haute-Provence in France and using the ELODIE spectrograph. On October 12, 1995, confirmation came from Geoffrey Marcy from San Francisco State University and Paul Butler from the University of California, Berkeley using the Hamilton Spectrograph at the Lick Observatory near San Jose in California.

51 Pegasi b (51 Peg b) is the first discovered planetary-mass companion of its parent star. After its discovery, many teams confirmed its existence and obtained more observations of its properties, including the fact that it orbits very close to the star, experiences estimated temperatures around 1200 °C, and has a minimum mass about half that of Jupiter. At the time, this close distance was not compatible with theories of planet formation and resulted in discussions of planetary migration. It has been assumed that the planet shares the star's inclination of 79 degrees.[22] However, several "hot Jupiters" are now known to be oblique relative to the stellar axis.[23]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (Dimidium) | ≥ 0.472 ± 0.039 MJ | 0.0527 ± 0.0030 | 4.230785 ± 0.000036 | 0.013 ± 0.012 | — | — |

See also

|

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. - 1 2 3 4 van Belle, Gerard T.; von Braun, Kaspar (2009). "Directly Determined Linear Radii and Effective Temperatures of Exoplanet Host Stars". The Astrophysical Journal (abstract). 694 (2): 1085–1098. arXiv:0901.1206

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...694.1085V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/1085.

. Bibcode:2009ApJ...694.1085V. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/1085. - 1 2 3 4 5 Poppenhäger, K.; et al. (December 2009), "51 Pegasi – a planet-bearing Maunder minimum candidate", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 508 (3): 1417–1421, arXiv:0911.4862

, Bibcode:2009A&A...508.1417P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912945

, Bibcode:2009A&A...508.1417P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912945 - 1 2 3 4 5 Monet, David G.; et al. (February 2003). "The USNO-B Catalog". The Astronomical Journal. 125 (2): 984–993. arXiv:astro-ph/0210694

. Bibcode:2003AJ....125..984M. doi:10.1086/345888.

. Bibcode:2003AJ....125..984M. doi:10.1086/345888. - 1 2 Johnson, H. L.; et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. 4 (99). Bibcode:1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- 1 2 Frasca, A.; et al. (December 2009). "REM near-IR and optical photometric monitoring of pre-main sequence stars in Orion. Rotation periods and starspot parameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 508 (3): 1313–1330. Bibcode:2009A&A...508.1313F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913327.

- 1 2 Simpson, E. K.; et al. (November 2010), "Rotation periods of exoplanet host stars", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 408 (3): 1666–1679, arXiv:1006.4121

, Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408.1666S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17230.x [as "HD 217014"]

, Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408.1666S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17230.x [as "HD 217014"] - ↑ Mamajek, Eric E.; Hillenbrand, Lynne A. (November 2008). "Improved Age Estimation for Solar-Type Dwarfs Using Activity-Rotation Diagnostics". The Astrophysical Journal. 687 (2): 1264–1293. arXiv:0807.1686

. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1264M. doi:10.1086/591785.

. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1264M. doi:10.1086/591785. - ↑ "51 Peg – Star suspected of Variability". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- 1 2 Mayor, Michael; Queloz, Didier (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature. 378 (6555): 355–359. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..355M. doi:10.1038/378355a0.

- ↑ "The Colour of Stars", Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, December 21, 2004, retrieved 2012-01-16

- ↑ Baliunas, Sallie; Sokoloff, Dmitry; Soon, Willie (1996). "Magnetic Field and Rotation in Lower Main-Sequence Stars: An Empirical Time-Dependent Magnetic Bode's Relation?". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 457 (2): L99–L102. Bibcode:1996ApJ...457L..99B. doi:10.1086/309891..

- ↑ Kukarkin, B. V.; et al. (1981). Nachrichtenblatt der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde e.V. (Catalogue of suspected variable stars). Moscow: Academy of Sciences USSR Shternberg. Bibcode:1981NVS...C......0K.

- ↑ University of California at Berkeley News Release 1996-17-01

- ↑ NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars. IAU.org. 9 July 2014

- ↑ NameExoWorlds The Process

- ↑ Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015.

- ↑ NameExoWorlds The Approved Names

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "51_peg_b". Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda; Josh N. Winn; Daniel C. Fabrycky (2012). "Starspots and spin-orbit alignment for Kepler cool host stars". arXiv:1211.2002

. Bibcode:2013AN....334..180S. doi:10.1002/asna.201211765.

. Bibcode:2013AN....334..180S. doi:10.1002/asna.201211765. - ↑ "First Exoplanet Visible Light Spectrum". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Butler, R. P.; et al. (2006). "Catalog of Nearby Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 646 (1): 505–522. arXiv:astro-ph/0607493

. Bibcode:2006ApJ...646..505B. doi:10.1086/504701.

. Bibcode:2006ApJ...646..505B. doi:10.1086/504701.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 51 Pegasi. |

- Jean Schneider (2011). "Notes for star 51 Peg". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- 51 Pegasi at SolStation.com.

- nStars database entry

- David Darling's encyclopedia

Coordinates: ![]() 22h 57m 28.0s, +20° 46′ 08″

22h 57m 28.0s, +20° 46′ 08″