Action of 9 February 1945

| Action of 9 February 1945 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second World War, Battle of the Atlantic | |||||||

_(IWM_FL_004031).jpg) HMS Venturer in August 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| V-class submarine HMS Venturer | Type IX U-boat, U-864 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| none |

Submarine sunk, All 73 crew killed | ||||||

The Action of 9 February 1945 refers to the sinking of the U-boat U-864 in the North Sea off the Norwegian coast during the Second World War by the Royal Navy submarine HMS Venturer. This action is the first and so far only incident of its kind in history where one submarine has intentionally sunk another submarine in combat while both were fully submerged.[2]

Background

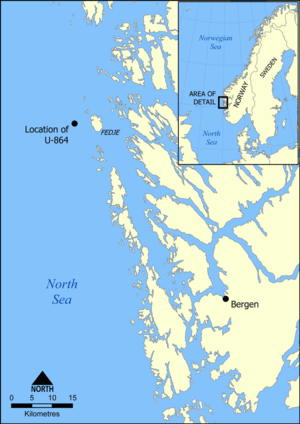

U-864 was a Type IX U-boat, designed for ocean-going voyages far from home ports with limited re-supply. She was on a long-range, covert mission codenamed Operation Caesar to deliver highly sensitive technology to Germany's wartime ally, the Empire of Japan. This included parts for jet engines and missile guidance systems, and 65 tonnes of mercury. She also carried Tadao Yamoto (a Japanese acoustic torpedo expert) and Toshio Nakai (a Japanese fuel expert). Also included were two Messerschmitt engineers, Rudolf ("Rolf") von Chlingensperg[3] and Riclef Schomerus.[1] On 6 February 1945, U-864 passed through the Fedje area (off the coast of Norway) without being detected. During this voyage a normally quiet engine began making an abnormally loud and rhythmic noise that could be easily detected by any ASW equipment in the area. There were many Allied (primarily British) ships, submarines and aircraft in the area on anti-submarine patrol. U-864's commander, Ralf-Reimar Wolfram, decided to return to the pens at Bergen to repair the engine.

By this stage of the war the German naval code, Enigma, had been broken by the Polish and was being decrypted by a team at Bletchley Park using a device called the Bombe. The German naval command was unaware that the British were reading communications sent to the U-boat fleet and so aware of Operation Caesar.[2] Wanting to avoid giving the Japanese any advantage that might allow them to extend the duration of the war in the Pacific, Royal Navy submarine command dispatched Venturer to intercept and destroy U-864.

Venturer was now on her eleventh patrol out of the British submarine base at Lerwick in the Shetland Islands. Under the command of 25-year-old Lieutenant Jimmy Launders, Venturer had sunk thirteen German vessels during ten patrols over the previous 12 months, including the destruction of the Type VIIc U-boat U-771 off the Lofoten Islands on 11 November 1944, seven nautical miles (13 km) east of Andenes.[2][4]

Launders received a brief message from Royal Navy Submarine Command as to the estimated whereabouts of U-864, that she was somewhere near the island of Fedje, off Norway's southwest coast, just north of the submarine pens at Bergen, along with instructions to destroy her. Launders set about the task, making one risky but calculated decision: he decided to switch off Venturer's ASDIC (sonar). They would rely solely on Venturer's hydrophone, a common and long-used, though far less sophisticated underwater acoustic detection device than ASDIC, to try to detect U-864 along the course that the Enigma-encoded traffic suggested.[2]

ASDIC is an early name for sonar, an active echo location system; it can quickly provide enough data on range and course for a target's speed and bearing to be calculated, and a firing solution for a weapon to be arrived at, even against a vessel taking evasive action. However – the ping given off can be heard by the target as well, it can also be heard much further away than the returned echo that indicated a target. Hydrophones are passive devices, very sensitive underwater directional microphones that an operator can use to tell where a noise is coming from by rotating the microphone and listening to from what direction the sound seems the loudest. Working out distance and exact speed are much more difficult, especially if a vessel takes evasive action (although rough speed can be discerned by how fast the enemies propeller and engine are spinning, and total volume gives a very rough idea of distance). In using hydrophones, the hunting vessel has to move quite slowly so as not to mask out any external noises by its own sounds. Launders' choice was to hide and see if he could hear the U-boat in the area. His plan was to listen for the German vessel and stalk her rather than risk alerting the enemy craft, although ASDIC would improve his chances of detecting her. He didn't need to worry about the German captain using sonar, because the Germans didn't have any.

The intelligence derived from the German messages led Launders' commanders to direct him to search for the German U-boat near Fedje but U-864 had already left the area on her mission to Japan. Wolfram's decision to return for repairs at the U-boat pens at Bergen to fix the abnormal engine noise problem brought U-864 back past Fedje and the area where Venturer was located.

The Action

As Venturer continued her patrol of the waters around Fedje, her hydrophone operator noticed a strange sound which he could not identify. He thought that the noise sounded as though some local fisherman had started up a boat's diesel engine.[2] Launders decided to track the strange noise. Then the officer of the watch on Venturer's periscope noticed what they thought was another periscope above the surface of the water.[2] However it is highly likely that what was seen was the U-boat's snorkel. The snorkel was still a new device, at that time, it was only used by German U-boats. It was probably unknown to Launders and his crew, which is why it was thought to be a periscope. The snorkel was a rigid 'breathing tube' raised to the surface to allow the U-boat to run on her diesels while submerged, saving precious battery life. It allowed air to enter both for the engines and the crew, plus it was also used as an outlet for exhaust fumes. Thicker and bulkier than a periscope, it also limited the U-boat's speed and depth. For Launders' hydrophone operator to hear diesel noises from a submerged U-boat, the snorkel would have had to be in operation. In addition, the noise of the diesel engines made the U-boat's own hydrophones much less effective and it is doubtful that the German hydrophone operator would have heard Venturer running slowly on her electric motors.

Combined with the hydrophone reports of the strange noise, which he determined to be coming from a submerged vessel, Launders surmised that they had found U-864.[2] Launders tracked the U-boat by hydrophone, hoping she would surface and allow a clear shot. But U-864 remained submerged, and as the hydrophone plot emerged, she was seen to be zigzagging. This made the German submarine quite safe according to the assumptions of the time.

Launders continued to track the U-boat. After several hours it became obvious that she was not going to surface, but he needed to attack her anyway – his batteries had only a limited life. It was theoretically possible to compute a firing solution in all four dimensions – time, distance, bearing and target depth – but this had never been attempted in practice because it was assumed that performing the complex calculations would be impossible, plus there were unknown factors that had to be approximated.

In most torpedo attacks, the target would have been visually acquired; the target's angle relative to the attacker and its bearing would be observed, then various range finding devices used to establish the distance to the target; from this speed could be derived, and a basic mechanical computer would offset the aiming point for the torpedo. In addition, any torpedo depth had to be set based on target identification. Too deep and the torpedo would pass under the target's keel, too shallow and it would not do as much damage, especially if the target was a warship with an armoured belt at the waterline. Launders could only estimate the depth of his target – and even then his torpedoes could go over or under the U-boat's hull. In terms of a challenge, this was far outside what they had trained for, as they tried to manoeuvre into a firing position without giving their own position away by creating excessive noise, or exhausting their own batteries.

Nevertheless, Launders and his crew made the necessary calculations, made assumptions about U-864's defensive manoeuvres, and ordered the firing of all torpedoes in the four bow tubes. As a small, fast-attack boat, Venturer was equipped with only four torpedo tubes, all in the bow, and carried only eight in total. The torpedoes were fired with a 17.5 second delay between each pair, and at variable depths. U-864 attempted to evade once it heard the torpedoes coming, but the Type IXD2 boats were large and not quick when diving or turning; additionally, time would have been needed to drop the snorkel, call the crew to action stations, disengage the diesel, and start the electric motors. The fourth torpedo struck the target. Her pressure hull punctured, U-864 instantaneously imploded with the loss of all hands.

Aftermath

U-864 sank 31 nautical miles (57 km) from the relative safety of the U-boat pens in Bergen. Launders was awarded a bar to his DSO for this action, while several members of Venturer's crew were decorated by the Royal Navy. Launders' career in the Navy continued well after the war.[5] The action was the first and so far only battle ever to have been fought entirely under water.[2]

The wreck of U-864 lies in 460 ft (140 m) of water 2.2 nmi (4.1 km) west of the island of Fedje, and was discovered in 2003. She remains an environmental hazard, due to her toxic cargo, but is classed as a war grave, and all maritime operations relating to the wreck, including environmental clean-up efforts, must adhere strictly to the international protocols dealing with treatment of such sites.[2]

See also

References

- Citations

- 1 2 "Salvage of U864 – Supplementary Studies – Study No. 7: Cargo" (PDF). Det Norske Veritas Report No. 23916. Det Norske Veritas. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. pg 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 U864: Hitler's Deadly Last Secret, Discovery Communications, 2006

- ↑ "Rudolf Heinrich Julius von Chlingensperg auf Berg, * 1904 - Geneall.net".

- ↑ "Listing of British Submarines of WW2".

- ↑ United Kingdom Royal Navy Museum, Commander Launders' Service Record, Public Records

- Bibliography

- Akermann, Paul (2002). Encyclopaedia of British Submarines 1901–1955. Periscope Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904381-05-1.

- External links

- "U-864: Hitler's Deadly Last Secret". History Television. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "HMS Venturer". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "U-864". German U-boats of WWII - uboat.net.