Alberto Giacometti

| Alberto Giacometti | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Portrait of Alberto-Giacometti, (etching by Jan Hladík, 2002) | |

| Born |

10 October 1901 Borgonovo, Stampa, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| Died |

11 January 1966 (aged 64) Chur, Graubünden, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Education | The School of Fine Arts, Geneva |

| Known for | Sculpture, Painting, Drawing |

| Movement | Surrealism, Expressionism, Cubism, Formalism |

| Spouse(s) | Annette Arm |

| Awards | "Grand Prize for Sculpture" at 1962 Venice Biennale |

Alberto Giacometti (Italian pronunciation: [alˈbɛrto dʒakoˈmetti]; 10 October 1901 – 11 January 1966) was a Swiss sculptor, painter, draughtsman and printmaker. He was born in the canton Graubünden's southerly alpine valley Val Bregaglia, as the eldest of four children to Giovanni Giacometti, a well-known post-Impressionist painter. Coming from an artistic background, he was interested in art from an early age.

Early life

_-_BEIC_6328562.jpg)

Giacometti was born in Borgonovo, now part of the Switzerland municipality of Bregaglia, near the Italian border. He was a descendant of Protestant refugees escaping the inquisition. Alberto attended the Geneva School of Fine Arts. His brothers Diego (1902–85) and Bruno (1907–2012) would go on to become artists as well. Additionally, Zaccaria Giacometti, later professor of constitutional law and chancellor of the University of Zurich grew up together with them, having been orphaned at the age of 12 in 1905.[1]

In 1922 he moved to Paris to study under the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, an associate of Rodin. It was there that Giacometti experimented with cubism and surrealism and came to be regarded as one of the leading surrealist sculptors. Among his associates were Miró, Max Ernst, Picasso, Bror Hjorth and Balthus.

Between 1936 and 1940, Giacometti concentrated his sculpting on the human head, focusing on the sitter's gaze. He preferred models he was close to, his sister and the artist Isabel Rawsthorne (then known as Isabel Delmer). This was followed by a phase in which his statues of Isabel became stretched out; her limbs elongated.[2] Obsessed with creating his sculptures exactly as he envisioned through his unique view of reality, he often carved until they were as thin as nails and reduced to the size of a pack of cigarettes, much to his consternation. A friend of his once said that if Giacometti decided to sculpt you, "he would make your head look like the blade of a knife". After his marriage to Annette Arm in 1946 his tiny sculptures became larger, but the larger they grew, the thinner they became. Giacometti said that the final result represented the sensation he felt when he looked at a woman.

His paintings underwent a parallel procedure. The figures appear isolated and severely attenuated, as the result of continuous reworking. Subjects were frequently revisited: one of his favorite models was his younger brother Diego Giacometti.[3] A third brother, Bruno Giacometti, was a noted architect.

Later years

In 1958 Giacometti was asked to create a monumental sculpture for the Chase Manhattan Bank building in New York, which was beginning construction. Although he had for many years "harbored an ambition to create work for a public square",[5] he "had never set foot in New York, and knew nothing about life in a rapidly evolving metropolis. Nor had he ever laid eyes on an actual skyscraper", according to his biographer James Lord.[6] Giacometti's work on the project resulted in the four figures of standing women—his largest sculptures—entitled Grande femme debout I through IV (1960). The commission was never completed, however, because Giacometti was unsatisfied by the relationship between the sculpture and the site, and abandoned the project.

In 1962, Giacometti was awarded the grand prize for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, and the award brought with it worldwide fame. Even when he had achieved popularity and his work was in demand, he still reworked models, often destroying them or setting them aside to be returned to years later. The prints produced by Giacometti are often overlooked but the catalogue raisonné, Giacometti – The Complete Graphics and 15 Drawings by Herbert Lust (Tudor 1970), comments on their impact and gives details of the number of copies of each print. Some of his most important images were in editions of only 30 and many were described as rare in 1970.

In his later years Giacometti's works were shown in a number of large exhibitions throughout Europe. Riding a wave of international popularity, and despite his declining health, he travelled to the United States in 1965 for an exhibition of his works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. As his last work he prepared the text for the book Paris sans fin, a sequence of 150 lithographs containing memories of all the places where he had lived.

Death

Giacometti died in 1966 of heart disease (pericarditis) and chronic bronchitis at the Kantonsspital in Chur, Switzerland. His body was returned to his birthplace in Borgonovo, where he was interred close to his parents. In May 2007 the executor of his widow's estate, former French foreign minister Roland Dumas, was convicted of illegally selling Giacometti's works to a top auctioneer, Jacques Tajan, who was also convicted. Both were ordered to pay €850,000 to the Alberto and Annette Giacometti Foundation.[7]

Artistic analysis

'%2C_painted_bronze_sculpture_by_Alberto_Giacometti%2C_1956%2C_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

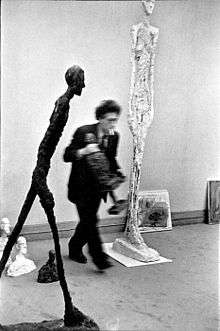

Photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Regarding Giacometti's sculptural technique and according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: "The rough, eroded, heavily worked surfaces of Three Men Walking (II), 1949, typify his technique. Reduced, as they are, to their very core, these figures evoke lone trees in winter that have lost their foliage. Within this style, Giacometti would rarely deviate from the three themes that preoccupied him—the walking man; the standing, nude woman; and the bust—or all three, combined in various groupings."[4]

In a letter to Pierre Matisse, Giacometti wrote: "Figures were never a compact mass but like a transparent construction".[8] In the letter, Giacometti writes about how he looked back at the realist, classical busts of his youth with nostalgia, and tells the story of the existential crisis which precipitated the style he became known for.

"[I rediscovered] the wish to make compositions with figures. For this I had to make (quickly I thought; in passing), one or two studies from nature, just enough to understand the construction of a head, of a whole figure, and in 1935 I took a model. This study should take, I thought, two weeks and then I could realize my compositions...I worked with the model all day from 1935 to 1940...Nothing was as I imagined. A head, became for me an object completely unknown and without dimensions."[8]

Since Giacometti achieved exquisite realism with facility when he was executing busts in his early adolescence, Giacometti's difficulty in re-approaching the figure as an adult is generally understood as a sign of existential struggle for meaning, rather than as a technical deficit.

Giacometti was a key player in the Surrealist art movement, but his work resists easy categorization. Some describe it as formalist, others argue it is expressionist or otherwise having to do with what Deleuze calls "blocs of sensation" (as in Deleuze's analysis of Francis Bacon). Even after his excommunication from the Surrealist group, while the intention of his sculpting was usually imitation, the end products were an expression of his emotional response to the subject. He attempted to create renditions of his models the way he saw them, and the way he thought they ought to be seen. He once said that he was sculpting not the human figure but "the shadow that is cast".

Scholar William Barrett in Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy (1962), argues that the attenuated forms of Giacometti's figures reflect the view of 20th century modernism and existentialism that modern life is increasingly empty and devoid of meaning. "All the sculptures of today, like those of the past, will end one day in pieces...So it is important to fashion ones work carefully in its smallest recess and charge every particle of matter with life."

A new exhibition in Paris, since September 2011, shows how Giacometti strongly drew his inspiration for his work from Etruscan art.[9]

Artworks by Giacometti at the 31° Venice Biennale in 1962

Legacy

Exhibitions

Giacometti's work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions including Pera Museum, Istanbul (2015) Pushkin Museum, Moscow (2008); “The Studio of Alberto Giacometti: Collection of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti”, Centre Pompidou, Paris (2007–2008); Kunsthal Rotterdam (2008); Fondation Beyeler, Basel (2009), Buenos Aires (2012); Kunsthalle Hamburg (2013), and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta (1970).

The National Portrait Gallery, London's first solo exhibition of Giacometti's work, Pure Presence opened to five star reviews on 13 October 2015 (to January 10, 2016, in honour of the fiftieth anniversary of the artist's death).[10][11]

Public collections

Giacometti's work is displayed in numerous public collections, including:

- Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo

- Art Institute of Chicago

- Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland

- Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, Charlotte, North Carolina

- Berggruen Museum, Berlin

- Botero Museum, Bogotá, Colombia

- Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, Switzerland

- Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

- Detroit Institute of Arts

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California

- Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

- Kunsthaus Zürich

- Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Republic of Korea[12]

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Museum of Modern Art, New York

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

- Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

- Tate, London

- Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Iran

- Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford

- Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

- University of Michigan Museum of Art

Art Foundations

The Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, having received a bequest from Alberto Giacometti's widow Annette, holds a collection of circa 5,000 works, frequently displayed around the world through exhibitions and long-term loans. A public interest institution, the Foundation was created in 2003 and aims at promoting, disseminating, preserving and protecting Alberto Giacometti's work.

The Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung established in Zürich in 1965, holds a smaller collection of works acquired from the collection of the Pittsburgh industrialist G. David Thompson.

Notable sales

In November 2000 a Giacometti bronze, Grande Femme Debout I, sold for $14.3 million.[13] Grande Femme Debout II was bought by the Gagosian Gallery for $27.4 million at Christie's auction in New York City on May 6, 2008.[14]

L'Homme qui marche I, a life-sized bronze sculpture of a man, became one of the most expensive works of art and the most expensive sculpture ever sold at auction on February 2, 2010, when it sold for £65 million (US$104.3 million) at Sotheby's, London.[15][16] Grande tête mince, a large bronze bust, sold for $53.3 million just three months later.

L'Homme au doigt (Pointing Man) sold for $126 million (£81314455.32), or $141.3 million with fees, in Christie's May 11, 2015 Looking Forward to the Past sale in New York, a record for a sculpture at auction. The work had been in the same private collection for 45 years.[17]

Other legacy

Giacometti created the monument on the grave of Gerda Taro at Père Lachaise Cemetery.[18]

In 2001 he was included in the Painting the Century: 101 Portrait Masterpieces 1900–2000 exhibition held at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

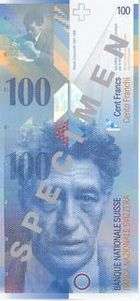

Giacometti and his sculpture L'Homme qui marche I appear on the current 100 Swiss Franc banknote.[19]

According to a lecture by Michael Peppiatt at Cambridge University on July 8, 2010, Giacometti, who had a friendship with author/playwright Samuel Beckett, created a tree for the set of a 1961 Paris production of Waiting for Godot.

Notes

- ↑ Andreas Kley: Von Stampa nach Zürich. Der Staatsrechtler Zaccaria Giacometti, sein Leben und Werk und seine Bergeller Künstlerfamilie, Zürich 2014, pp. 89 et seq.

- ↑ New York Times article on The Women of Giacometti exhibition, Pace Wildenstein Gallery 2005

- ↑ Tate Collection: Seated Man by Alberto Giacometti Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- 1 2 Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Christie's, Impressionist And Modern Art Evening Sale, New York, Rockefeller Plaza, 6 May 2008

- ↑ James Lord, Giacometti: A Biography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1986, pp. 331–332 ISBN 978-0-374-52525-5

- ↑ "Conviction Upheld Against mFormer French FM in Giacometti Fraud". May 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- 1 2 Introduction by Peter Selz, autobiographical statement by Giacometti (1965). Alberto Giacometti (PDF). Garden City, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, in collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago. pp. 14–28.

- ↑ Giacometti and The Etruscans, La Pinacothèque de Paris

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (13 October 2015). "Giacometti: Pure Presence review – the most profound, universal art of the past 75 years". Guardian online. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ Luke, Ben (13 October 2015). "Giacometti: Pure Presence, exhibition review: Profound portrait of the artist's progress". Evening Standard online. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art

- ↑ "Art record Picasso painting goes for £39m at auction". The Guardian. London. 2000-11-10. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ↑ Afp.google.com, Monet fetches record price at New York auction

- ↑ Giacometti sculpture fetches £65m at Sotheby's auction

- ↑ Alberto Giacometti's Walking Man I Sells for a Record-Breaking $104,327,006 at Sotheby's

- ↑ Reyburn, Scott (11 May 2015). "Two Artworks Top $100 Million Each at Christie's Sale (Artsbeat blog)". New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Robert Whelan, "Robert Capa, the definitive collection", p. 8, Phaidon press 2001, ISBN 978-0-7148-4449-7

- ↑ Schweizer Nationalbank

References

- Jacques Dupin (1962) "Alberto Giacometti", Paris, Maeght

- Reinhold Hohl (1971) "Alberto Giacometti", Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje

- Die Sammlung der Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung (1990), Zürich, Zürcher Kunstgesellschaft

- Alberto Giacometti. Sculptures – peintures – dessins. Paris, Musée d'art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1991–92.

- Jean Soldini (1993) "Alberto Giacometti. Le colossal, la mère, le sacré", Lausanne, L'Age d'Homme

- David Sylvester (1996) Looking at Giacometti, Henry Holt & Co.

- Alberto Giacometti 1901–1966. Kunsthalle Wien, 1996

- James Lord (1997) Giacometti: A Biography, Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Alberto Giacometti. Kunsthaus Zürich, 2001; New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2001–2002.

- Yves Bonnefoy (2006) Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work, New edition, Flammarion

- Weiland, Andreas (January 25, 2009). "The Sculptures of Alberto Giacometti / Seen in the Kunsthal Rotterdam (Giacometti Exhibition, October 18, 2008 – February 8, 2009)". Art in Society. ISSN 1618-2154. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27.

- Wilson, Laurie (2003). Alberto Giacometti: Myth, Magic and the Man. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300090374. Archived from the original on 2006-09-14.

Bibliography

- Alberto Giacometti, Yves Bonnefoy, Assouline Publishing (February 22, 2011)

- In Giacometti's Studio, Michael Peppiatt, Yale University Press (December 14, 2010)

- Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work, Yves Bonnefoy, New edition, Flammarion (2006)

- Giacometti: A Biography, James Lord, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (1997)

- Looking at Giacometti, David Sylvester, Henry Holt & Co. (1996)

- Alberto Giacometti, Herbert Matter & Mercedes Matter, Harry N Abrams (September 1987)

- A Giacometti Portrait, James Lord, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (July 1, 1980)

- Alberto Giacometti, Reinhold Hohl, H. N. Abrams (1972)

- Alberto Giacometti, Reinhold Hohl, Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje (1971)

- Alberto Giacometti, Jacques Dupin, Paris, Maeght(1962)

- The Studio of Alberto Giacometti: Collection of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Véronique Wiesinger (ed.), exh. cat., Paris: Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti/Centre Pompidou (2007) ISBN 978-2-84426-352-0

- "The Dream, the Sphinx, and the Death of T", Alberto Giacometti, X magazine, Vol.1, No.1 (November 1959); An Anthology from X (Oxford University Press 1988).

- Matter, Mercedes (Jan 28, 1966). A Life Spent in Pursuit of the Impossible. 60. LIFE. pp. 54–60. ISSN 0024-3019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alberto Giacometti. |

- The Alberto et Annette Giacometti Foundation website:

- "Alberto Giacometti". SIKART dictionary and database.

- Publications by and about Alberto Giacometti in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Works of Alberto Giacometti:

- Life of Alberto Giacometti:

- Chronology of his life with illustrations from the Museum of Modern Art

- Exhibition at Kunsthaus Zürich from 27 February until 24 May 2009

- Alberto Giacometti in the National Gallery of Australia's Kenneth Tyler Collection

- Alberto Giacometti in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

_-_BEIC_6328561.jpg)

_-_BEIC_6356049.jpg)

_-_BEIC_6363726.jpg)

_-_BEIC_6328565.jpg)