Alex Haley

| Alex Haley | |

|---|---|

Haley during his tenure in the U.S. Coast Guard | |

| Born |

Alexander Murray Palmer Haley August 11, 1921 Ithaca, New York, United States[1] |

| Died |

February 10, 1992 (aged 70) Seattle, Washington, United States |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater |

Alcorn State University Elizabeth City State College |

| Spouse |

Nannie Branch (1941–1964) Juliette Collins (1964–1972) Myra Lewis (1977–1992)[2] (his death) |

|

Military career | |

| Allegiance | US |

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1939–1959 |

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Alexander Murray Palmer "Alex" Haley (August 11, 1921 – February 10, 1992)[1] was an American writer and the author of the 1976 book Roots: The Saga of an American Family. ABC adapted the book as a television miniseries of the same name and aired it in 1977 to a record-breaking audience of 130 million viewers. In the United States the book and miniseries raised the public awareness of African American history and inspired a broad interest in genealogy and family history.

Haley's first book was The Autobiography of Malcolm X, published in 1965, a collaboration through numerous lengthy interviews with the subject, a major African-American leader.[3][4][5]

He was working on a second family history novel at his death. Haley had requested that David Stevens, a screenwriter, complete it; the book was published as Alex Haley's Queen. It was adapted as a film of the same name released in 1993.

Early life and education

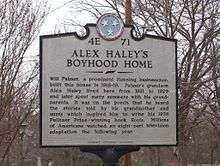

Alex Haley was born in Ithaca, New York, on August 11, 1921, and was the oldest of three brothers and a sister. Haley lived with his family in Henning, Tennessee, before returning to Ithaca with his family when he was five years old. Haley's father was Simon Haley, a professor of agriculture at Alabama A&M University, and his mother was Bertha George Haley (née Palmer), who had grown up in Henning. The family had African American, Mandinka, Cherokee, Scottish, and Scots-Irish roots.[6][7][8][9] The younger Haley always spoke proudly of his father and the obstacles of racism he had overcome.

Like his father, Alex Haley was enrolled at age 15 in Alcorn State University, a historically black college in Mississippi and, a year later, enrolled at Elizabeth City State College, also historically black, in North Carolina. The following year he returned to his father and stepmother to tell them he had withdrawn from college. His father felt that Alex needed discipline and growth, and convinced him to enlist in the military when he turned 18. On May 24, 1939, Alex Haley began what became a 20-year career in the United States Coast Guard.[10]

Haley traced back his paternal ancestry, through genealogical research, to Jufureh.[11]

Coast Guard career

Haley enlisted as a mess attendant. Later he was promoted to the rate of petty officer third-class in the rating of steward, one of the few ratings open to African Americans at that time.[12] It was during his service in the Pacific theater of operations that Haley taught himself the craft of writing stories. During his enlistment other sailors often paid him to write love letters to their girlfriends. He said that the greatest enemy he and his crew faced during their long voyages was not the Japanese forces but rather boredom.[10]

After World War II, Haley petitioned the U.S. Coast Guard to allow him to transfer into the field of journalism. By 1949 he had become a petty officer first-class in the rating of journalist. He later advanced to chief petty officer and held this grade until his retirement from the Coast Guard in 1959. He was the first chief journalist in the Coast Guard, the rating having been expressly created for him in recognition of his literary ability.[10]

Haley's awards and decorations from the Coast Guard include the Coast Guard Good Conduct Medal (with 1 silver and 1 bronze service star), American Defense Service Medal (with "Sea" clasp), American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Korean Service Medal, National Defense Service Medal, United Nations Service Medal, and the Coast Guard Expert Marksmanship Medal.[10] Further, the Republic of Korea awarded him the War Service Medal 10 years after he died.

Literary career

After retiring from the U.S. Coast Guard, Haley began another phase of his journalism career. He eventually became a senior editor for Reader's Digest magazine.

Playboy magazine

Haley conducted the first interview for Playboy magazine. His interview with jazz musician Miles Davis appeared in the September 1962 issue. Haley elicited candid comments from Davis about his thoughts and feelings on racism. That interview set the tone for what became a significant feature of the magazine. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Playboy Interview with Haley was the longest he ever granted to any publication.[13]

Throughout the 1960s Haley was responsible for some of the magazine's most notable interviews, including one with George Lincoln Rockwell, leader of the American Nazi Party. He agreed to meet with Haley only after gaining assurance from the writer that he was not Jewish. Haley remained professional during the interview, although Rockwell kept a handgun on the table throughout it. (The interview was recreated in Roots: The Next Generations, with James Earl Jones as Haley and Marlon Brando as Rockwell.)[14] Haley also interviewed Muhammad Ali, who spoke about changing his name from Cassius Clay. Other interviews include Jack Ruby's defense attorney Melvin Belli, entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr., football player Jim Brown, TV host Johnny Carson, and music producer Quincy Jones.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, published in 1965, was Haley's first book.[15] It describes the trajectory of Malcolm X's life from street criminal to national spokesman for the Nation of Islam to his conversion to Sunni Islam. It also outlines Malcolm X's philosophy of black pride, black nationalism, and pan-Africanism. Haley wrote an epilogue to the book summarizing the end of Malcolm X's life, including his assassination in New York's Audubon Ballroom.

Haley ghostwrote The Autobiography of Malcolm X based on more than 50 in-depth interviews he conducted with Malcolm X between 1963 and Malcolm X's February 1965 assassination.[16] The two men had first met in 1960 when Haley wrote an article about the Nation of Islam for Reader's Digest. They met again when Haley interviewed Malcolm X for Playboy.[16]

The first interviews for the autobiography frustrated Haley. Rather than discussing his own life, Malcolm X spoke about Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam; he became angry about Haley's reminders that the book was supposed to be about Malcolm X. After several meetings, Haley asked Malcolm X to tell him something about his mother. That question drew Malcolm X into recounting his life story.[16][17]

The Autobiography of Malcolm X has been a consistent best-seller since its 1965 publication.[18] The New York Times reported that six million copies of the book had sold by 1977.[4] In 1998 TIME magazine ranked The Autobiography of Malcolm X as one of the 10 most influential nonfiction books of the 20th century.[19]

In 1966 Haley received the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for The Autobiography of Malcolm X.[20]

Super Fly T.N.T.

In 1973 Haley wrote his only screenplay, Super Fly T.N.T.. The film starred and was directed by Ron O'Neal.

Roots

In 1976 Haley published Roots: The Saga of an American Family, a novel based on his family's history, going back to slavery days. It started with the story of Kunta Kinte, who was kidnapped in the Gambia in 1767 and transported to the Province of Maryland to be sold as a slave. Haley claimed to be a seventh-generation descendant of Kunta Kinte, and his work on the novel involved twelve years of research, intercontinental travel, and writing. He went to the village of Juffure, where Kunta Kinte grew up and listened to a tribal historian (griot) tell the story of Kinte's capture.[1] Haley also traced the records of the ship, The Lord Ligonier, which he said carried his ancestor to the Americas .

Haley has stated that the most emotional moment of his life occurred on September 29, 1967, when he stood at the site in Annapolis, Maryland, where his ancestor had arrived from Africa in chains exactly 200 years before. A memorial depicting Haley reading a story to young children gathered at his feet has since been erected in the center of Annapolis.

Roots was eventually published in 37 languages. Haley won a special Pulitzer Prize for the work in 1977.[21] The same year, Roots was adapted as a popular television miniseries of the same name by ABC. The serial reached a record-breaking 130 million viewers. Roots emphasized that African Americans have a long history and that not all of that history is necessarily lost, as many believed. Its popularity also sparked a greatly increased public interest in genealogy.[1]

In 1979 ABC aired the sequel miniseries, Roots: The Next Generations, which continued the story of Kunta Kinte's descendants. It concluded with Haley's travel to Juffure. Haley was portrayed at different ages by Kristoff St. John, The Jeffersons actor Damon Evans, and Tony Award winner James Earl Jones. In 2016, History aired a remake of the original miniseries. Haley appeared briefly, portrayed by Tony Award winner Laurence Fishburne.

Haley was briefly a "writer in residence" at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, where he began work on Roots. He enjoyed spending time at a local bistro called the Savoy in nearby Rome, where he would sometimes pass the time listening to the piano player. Today, there is a special table in honor of Haley at the Savoy, and a painting of Haley writing Roots on a yellow legal tablet.

Plagiarism dispute and other criticism

Roots faced two lawsuits that charged plagiarism and copyright infringement. The lawsuit brought by Margaret Walker was dismissed, but Harold Courlander's suit was successful. Courlander's novel The African describes an African boy who is captured by slave traders, follows him across the Atlantic on a slave ship, and describes his attempts to hold on to his African traditions on a plantation in America. Haley admitted that some passages from The African had made it into Roots, settling the case out of court.[22]

Genealogists have also disputed Haley's research and conclusions in Roots. The Gambian griot turned out not to be a real griot, and the story of Kunta Kinte appears to have been a case of circular reporting, in which Haley's own words were repeated back to him.[23][24] None of the written records in Virginia and North Carolina line up with the Roots story until after the Civil War. Some elements of Haley's family story can be found in the written records, but the most likely genealogy would be different from the one described in Roots.[25]

Haley and his work have been excluded from the Norton Anthology of African-American Literature, despite his status as the United States' best-selling African-American author. Harvard University professor Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., one of the anthology's general editors, has denied that the controversies surrounding Haley's works are the reason for this exclusion. In 1998 Dr. Gates acknowledged the doubts surrounding Haley's claims about Roots, saying, "Most of us feel it's highly unlikely that Alex actually found the village whence his ancestors sprang. Roots is a work of the imagination rather than strict historical scholarship."[26]

Later life and death

Early in the 1980s Haley worked with the Walt Disney Company to develop an Equatorial Africa pavilion for its Epcot Center theme park. Haley appeared on a CBS broadcast of Epcot Center's opening day celebration, discussing the plans and exhibiting concept art with host Danny Kaye. Ultimately, the pavilion was not built due to political and financial issues.[27]

Late in the 1970s Haley had begun working on a second historical novel based on another branch of his family, traced through his grandmother Queen; she was the daughter of a black slave woman and her white master. He did not finish the novel before dying in Seattle, Washington, of a heart attack. He was buried beside his childhood home in Henning, Tennessee. At his request, the novel was finished by David Stevens and was published as Alex Haley's Queen. It was subsequently adapted as a movie of the same name in 1993.

Late in Haley's life he had acquired a small farm in Norris, Tennessee, adjacent to the Museum of Appalachia, intending to live there. After his death the property was sold to the Children's Defense Fund (CDF), which calls it the Alex Haley Farm. The nonprofit organization uses the farm as a national training center and retreat site. An abandoned barn on the farm property was rebuilt as a traditional cantilevered barn, using a design by architect Maya Lin. The building now serves as a library for the CDF.[28]

Awards and recognition

- In 1977 Haley received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, for his exhaustive research and literary skill combined in Roots.[29]

- The food-service building at the U.S. Coast Guard Training Center, Petaluma, California, was named Haley Hall in honor of the author.

- In 1999 the Coast Guard honored Haley by naming the cutter USCGC Alex Haley after him.[30]

- The U.S. Coast Guard annually awards the Chief Journalist Alex Haley Award, which is named in honor of the writer as the Coast Guard's first chief journalist (the first Coast Guardsman in the rating of journalist to be advanced to the rate of chief petty officer). It rewards individual authors and photographers who have had articles or photographs communicating the Coast Guard story published in internal newsletters or external publications.[31]

- In 2002 the Republic of Korea (South Korea) posthumously awarded Haley its Korean War Service Medal (created in 1951), which the U.S. government did not allow its service members to accept until 1999.[32][33]

Recordings

- Alex Haley Tells the Story of His Search for Roots (1977) – 2-LP recording of a two-hour lecture Haley gave at the University of Pennsylvania. Released by Warner Bros. Records (2BS 3036).

Legacy

Collection of Alex Haley's personal works

The University of Tennessee Libraries, in Knoxville, Tennessee, maintains a collection of Alex Haley's personal works in its Special Collections Department. The works contain notes, outlines, bibliographies, research, and legal papers documenting Haley's Roots through 1977. Of particular interest are the items showing Harold Courlander's lawsuit against Haley, Doubleday & Company, and various affiliated groups.[34]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Wynn, Linda T. "Alex Haley, (1921–1992)". Tennessee State University Library. Archived from the original on August 3, 2004. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ↑ "The anguish of Alex Haley's widow with her husband's literary legacy dispersed, she's locked in a bitter probate battle". Phoenix New Times. November 11, 1992.

- ↑ Stringer, Jenny (ed), The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English (1986), Oxford University Press, p 275

- 1 2 Pace, Eric (February 2, 1992). "Alex Haley, 70, Author of 'Roots,' Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ↑ Perks, Robert; Thomson, Alistair, eds. (2003) [1998]. The Oral History Reader. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-415-13351-7.

- ↑ "Roots author had Scottish blood". March 1, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- ↑ David Lowenthal. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. p. 218.

- ↑ Marc R. Matrana. Lost Plantations of the South. p. 117.

- ↑ "DNA testing: 'Roots' author Haley rooted in Scotland, too". April 7, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 African Americans in the U.S. Coast Guard, US Coast Guard Historians Office

- ↑ "Alex Haley Mosque opens". The Final Call. July 13, 1999.

- ↑ Packard, Jerrold M. (2002). American Nightmare: The History of Jim Crow. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 189. ISBN 0-312-26122-5.

- ↑ "Martin Luther King Jr.: A Candid Conversation With the Nobel Prize-Winning Civil Rights Leader". Playboy. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Les (February 15, 1979). "TV Sequel to 'Roots': Inevitable Question". The New York Times. Retrieved June 5, 2016. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Text Malcolm X Edited Found in Writer's Estate". The New York Times. September 11, 1992. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Haley, "Alex Haley Remembers", pp 243–244.

- ↑ "The Time Has Come (1964–1966)". Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Movement 1954–1985, American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on April 23, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ↑ Seymour, Gene (November 15, 1992). "What Took So Long?". Newsday. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ↑ Gray, Paul (June 8, 1998). "Required Reading: Nonfiction Books". Time. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards – Winners by Year – 1966". Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Special Awards and Citations". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

- ↑ Stanford, Phil (April 8, 1979). "Roots and Grafts on the Haley Story". The Washington Star. p. F.1.

- ↑ Ottaway, Mark (April 10, 1977). "Tangled Roots". The Sunday Times. pp. 17, 21.

- ↑ MacDonald, Edgar. "A Twig Atop Running Water – Griot History," Virginia Genealogical Society Newsletter, July/August 1991

- ↑ Mills, Elizabeth Shown; Mills, Gary B. (March 1984). "The Genealogist's Assessment of Alex Haley's Roots". National Genealogical Society Quarterly. 72 (1).

- ↑ Beam, Alex (October 30, 1998). "The Prize Fight Over Alex Haley's Tangled 'Roots'". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Hill, Jim (June 12, 2006). "Equatorial Africa: The World Showcase Pavilion that We Almost Got". Jim Hill Media. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Museum staff members visit Alex Haley Farm", Museum of Appalachia Newsletter, June 2006.

- ↑ NAACP Spingarn Medal

- ↑ Alex Haley USCG cutter, US Coast Guard

- ↑ Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25D (May 2008), US Coast Guard

- ↑ "Republic of Korea Korean War Service Medal". United States Army Human Resources Command. United States Army. April 11, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Republic of Korea Korean War Service Medal". Air Force Personnel Center. United States Air Force. August 5, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ Haley, Alex. "Alex Haley Papers". Alex Haley Papers. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

References cited

- "African Americans in the U.S. Coast Guard". US Coast Guard Historians Office. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- "Chief Journalist Alex Haley Award" (pdf). Medals and Awards Manual, COMDTINST M1650.25D (May 2008). US Coast Guard. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- "Text Malcolm X Edited Found in Writer's Estate". The New York Times. September 11, 1992. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- "The Time Has Come (1964–1966)". Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Movement 1954–1985, American Experience. PBS. Archived from the original on April 23, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- Haley, Alex (1992). "Alex Haley Remembers". In Gallen, David. Malcolm X: As They Knew Him. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-88184-850-6. Originally published in Essence, November 1983.

- Perks, Robert; Thomson, Alistair, eds. (2003) [1998]. The Oral History Reader. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-13351-7.

- Stringer, Jenny, ed. (1986). The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-212271-1.

- Wynn, Linda T. "Alex Haley, (1921–1992)". Tennessee State University Library. Archived from the original on August 3, 2004. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alex Haley |

- Alex Haley Roots Foundation

- Alex Haley Tribute Site

- Alex Haley (Open Library)

- Alex Haley at the Internet Movie Database

- The Kunta Kinte–Alex Haley Foundation

- Official Roots: 30th Anniversary Edition website

- Alex Haley at Library of Congress Authorities, with 41 catalog records