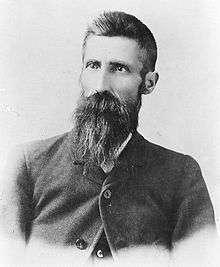

Alfred Alexander Freeman

| Alfred Alexander Freeman | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Assistant Attorney General for the Post Office Department | |

|

In office 1877–1885 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Ara Spence |

| Succeeded by | Edwin E. Bryant |

| Member of the Tennessee House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1865–1866 | |

| Preceded by | W.P. Bond |

| Succeeded by | J.A. Moore |

|

In office 1871–1872 | |

| Preceded by | J.W. Clarke |

| Succeeded by | W.W. Rutledge |

|

In office 1876–1877 | |

| Preceded by | Lewis Bond |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Alexander |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

February 7, 1838 Haywood County, Tennessee, United States |

| Died |

March 27, 1926 (aged 88) Victoria, British Columbia, Canada |

| Resting place |

Royal Oak Burial Park Victoria, British Columbia[1] |

| Political party | Republican |

| Profession | Attorney |

Alfred Alexander Freeman (February 7, 1838 – March 27, 1926) was an American politician, judge and diplomat, active during the latter half of the 19th century. He served several terms in the Tennessee House of Representatives in the years following the Civil War, and was the Republican nominee for Governor of Tennessee in 1872. He also served as United States Assistant Attorney General for the Post Office Department from 1877 to 1885, territorial judge of New Mexico from 1890 to 1895, and United States Consul to Prague in 1873. He established a lumber company in British Columbia in the early 1900s.[2]

Early life

Freeman was born in Haywood County, Tennessee,[2] the son of Green Freeman (1795–1875).[3] He attended school only sporadically as a child, and left home at the age of 17.[4] He studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1859. He supported the Union during the Civil War.[2]

Postwar Tennessee politics

Freeman was elected to Haywood County's vacant seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives in July 1865.[5] His term began in October of that year.[6] He joined the legislature's Conservative faction, which generally supported the policies of President Andrew Johnson and opposed the Radical Republican agenda of Governor William G. Brownlow. In March 1866, Freeman was among the legislators who broke quorum in an attempt to prevent the passage of a controversial franchise bill that would have given Brownlow unprecedented power over state elections. His seat was declared vacant as a result.[7]

In July 1866, Freeman was appointed vice president of the state's Conservative Republican convention in Memphis. He was a delegate to the National Union Convention in Philadelphia later that year.[8]

Following the enactment of the state's 1870 constitution, Freeman was nominated as a Republican candidate for the Tennessee Supreme Court. During the campaign, John Freeman, a brother of candidate Thomas J. Freeman (John and Thomas were not related to Alfred), published a scathing article in the Brownsville Bee insulting Alfred Freeman's competence as a lawyer. Alfred demanded a retraction, but John refused. On August 2, 1870, the two men met on the courthouse square in Brownsville to settle the matter. According to one newspaper report, when Alfred had approached to within twenty paces, John drew a gun and fired, but missed. Alfred returned fire, and a general firing between the two commenced. John was shot in the arm, while Alfred remained unharmed. After the shooting had stopped, John charged Alfred and wounded him with a bowie knife before friends finally separated them.[9]

Freeman was defeated in the judicial elections in August 1870. A month later, however, he was nominated as the Republican candidate for Haywood's seat in the Tennessee House, and was easily elected in November. Former Confederates had been reenfanchised in 1870, and Democrats had regained control of the state government. Freeman was the only Republican in the House from West Tennessee.[4]

In December 1871, Freeman was involved in a contentious debate on the House floor over a resolution introduced by Democrats which suggested the Ku Klux Klan no longer existed as an organization requiring the state's attention. Freeman, who had faced threats from the Klan, blasted the resolution, arguing that regardless of whether the "organization" existed, the "individuals" who comprised the organization still existed, and stated "if you will hang them and stop their depredations the country cares but little what becomes of the organization." When Representative B.A. Enloe asked by which senses, "seeing, feeling or smelling," Freeman had acquired his evidence, Freeman responded, "By all three. They look like fiends, feel like toads and smell like dogs." Representative R.M. Cheatham then asked how Freeman had even made it to Nashville if the Klan were such a dangerous threat, to which Freeman responded, "I have said to them as I still say to them, that my blood is at their disposal whenever they think that they have a sufficient amount of their own to give in exchange for it."[10]

In September 1872, Freeman was nominated as the Republican Party candidate for governor.[11] He spent September and October of that year campaigning and debating the Democratic Party incumbent, former Confederate general John C. Brown. At a debate in Lebanon, Brown blamed the state's growing debt crisis on Republicans, specifically the Brownlow administration. He opposed fixing the debt or funding public schools with tax increases. He blasted the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant as corrupt. In response, Freeman blamed the debt on pre-war Democratic governors, and argued that debts incurred under Brownlow were to rebuild railroads destroyed during the war. He supported a tax to fund public schools, and accused Democrats of stealing the state's school fund when they fled Nashville in early 1862.[12]

On election day, Brown defeated Freeman, 97,700 votes to 84,089. Freeman netted a higher percentage of the vote (46%) than the Republican candidates in the 1872, 1876 and 1878 elections, and more than double the total number of votes received by the party's 1870 candidate, William H. Wisener.[13]

Post-gubernatorial campaign career

In May 1873, President Grant appointed Freeman United States Consul to Prague, which at the time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[14] He departed for his post in June 1873,[15] but by October 1873 he had inexplicably returned home to Haywood County.[16] In a later interview, Freeman stated he had suffered from extreme loneliness and isolation in Prague, due in large part to the language barrier.[17]

In 1874, Freeman again sought election to Haywood's seat in the Tennessee House of Representatives, but was narrowly defeated by Lewis Bond, 2,008 votes to 1,831.[18] In April 1876, Freeman purchased the printing press of the defunct Brownsville Bee, and began publishing a pro-Republican newspaper, the Brownsville Free Press.[19] In May 1876, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention, where he served on the Committee on Resolutions.[20] Later that year, he once again sought Haywood's seat in the Tennessee House, and sold the Free Press in October 1876 to focus on his campaign.[21] In the November election, he defeated the Democratic candidate, John R. Bond.[22]

In April 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Freeman United States Assistant Attorney General for the Post Office Department, a position which oversaw the Postal Service's legal affairs. He obtained this appointment in part due to his friendship with Postmaster General David M. Key.[23][24] In October 1879, Freeman issued a ruling authorizing the Postal Service to withhold letters addressed to lottery companies.[25] This led to a string of lawsuits, and Freeman spent much of his term defending the ruling.[26][27] He also argued the federal government's case in Dauphin v. Key, which involved fraudulent mail schemes (and stemmed in part from the lottery ruling),[28][29] and advised against the formation of controversial star routes.[30]

During the 1880 presidential race, Freeman campaigned for former President Grant, who was seeking an unprecedented third term.[31] In March 1882, Freeman delivered a speech before the National Republican League opposing a pardon for William Mason, a guard who had attempted to kill Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President James Garfield.[32] After his term as Assistant Attorney General had ended in 1885, Freeman formed a Washington-based law partnership with ex-Congressman Hernando Money.[33]

New Mexico

In 1890, Congress created a fifth judicial district in the New Mexico Territory. The district covered Socorro, Lincoln, Chaves, and Eddy counties. President Benjamin Harrison appointed Freeman to the new judgeship in October 1890, after former Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed turned it down.[2] Along with Freeman, the fifth district court included his son-in-law John W. Garner as clerk, Albert Jennings Fountain (who had defended Billy the Kid) as district attorney, and former congressional delegate Trinidad Romero as U.S. Marshal.[34]

New Mexico's district judges were also members of the territorial appeals court, and one of the first (and most important) cases Freeman decided was an appeal involving the Shalam Colony, a religious colony that had been established in 1884. One of the colonists, Jessie Ellis, had sued the colony in 1887, alleging its founders had abandoned the colony's original ideals. A district court had ruled in favor of Ellis and awarded him monetary damages. Freeman reversed the decision, however, and blasted the district court ruling in such mocking fashion that President Harrison was rumored to have considered removing him from the bench. Freeman's opinion in the Shalam case has been cited in cases involving breach of religious doctrine.[2]

During the 1890s, Freeman and deputy U.S. marshal Dee Harkey used the 1882 Edmunds Act (which outlawed polygamy) to end prostitution in the town of Eddy (modern Carlsbad). This brought death threats from a local crime syndicate, but by the Summer of 1895, most of the town's prostitutes and saloon owners had moved to the Arizona Territory.[35]

After his term ended in early 1895, Freeman briefly formed a law partnership with former lawman Elfego Baca,[36] Freeman having previously granted Baca a law license.[37] Freeman later established a practice with his son-in-law, James O. Cameron (who had married his daughter, Beatrix).[2] In 1898, he was part of the defense team that won an acquittal for Eddy County sheriff David L. Kemp, who had been charged with murder.[38] In 1900, he was elected President of the New Mexico Bar.[2]

Later life

In late 1907, Freeman and his family moved to British Columbia, where he and his son-in-law, James O. Cameron, established a lumber company.[39] He spent his later years working as vice president of this company.[40] He died in Victoria on March 27, 1926.[2] Freeman and his family are interred in Victoria's Royal Oak Burial Park.[1]

A house Freeman once owned at 1261 Richardson Street in Victoria is listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places.[41]

References

- 1 2 British Columbia Cemetery Finding Aid (Version2). Accessed: 6 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mark Thompson, "President Benjamin Harrison, Judge A.A. Freeman and the Shalam Colony," Southern New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. XVI (January 2009), pp. 7-12. Retrieved: 6 July 2014.

- ↑ "Mr. Green Freeman," Memphis Public Ledger, 18 September 1875, p. 2.

- 1 2 The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 24 (Southern Illinois University Press, 1967), p. 323.

- ↑ "Night Dispatches," Nashville Daily Union, 8 August 1865, p. 3.

- ↑ "Tennessee Legislature," Nashville Daily Union, 4 October 1865, p. 2.

- ↑ "A Vindication: Our Conservative Representatives to the People of Tennessee," Clarksville Weekly Chronicle, 2 March 1866, p. 2.

- ↑ "Convention in Court Square," Memphis Public Ledger, 26 July 1866, p. 3.

- ↑ "Blood At Brownsville," Memphis Public Ledger, 3 August 1870, p. 3.

- ↑ "Representative Freeman on the Kuklux," Knoxville Daily Chronicle, 20 December 1871, p. 1.

- ↑ "The Radical Convention," Nashville Union and American, 5 September 1872, p. 4.

- ↑ "The Gubernatorial Race," Nashville Union and American, 18 September 1872, p. 4.

- ↑ Tennessee Blue Book (1890), p. 170.

- ↑ "A Tennessee Appointment," Knoxville Daily Chronicle, 18 May 1873, p. 4.

- ↑ "Local Paragraphs," Memphis Daily Appeal, 11 June 1873, p. 4.

- ↑ "Hon. A.A. Freeman," Jackson (TN) Whig and Tribune, 4 October 1873, p. 3.

- ↑ "Too Lonesome in Prague," San Juan County Index, 31 July 1903, p. 3.

- ↑ "Election Returns," Nashville Union and American, 10 November 1874, p. 3.

- ↑ "Current Topics," The Pulaski Citizen, 6 April 1876, p. 4.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Republican National Convention (Republican Press Association, 1876), p. 13.

- ↑ "Hon. A.A. Freeman," The Pulaski Citizen, 5 October 1876, p. 2.

- ↑ "The Brownsville Democracy," Memphis Daily Appeal, 19 October 1876, p. 1.

- ↑ Gaskell's Compendium of Forms (Bryan, Taylor and Company, 1885), p. 654.

- ↑ "A.A. Freeman," Cleveland (TN) Weekly Herald, 12 April 1877, p. 3.

- ↑ Wayne Edison Fuller, Morality and the Mail in Nineteenth-Century America (University of Illinois Press, 2003), p. 200.

- ↑ "Louisville Lottery Letters," Cincinnati Daily Star, 25 October 1879, p. 1.

- ↑ "The Lottery Case in New Orleans," Washington Evening Star, 26 December 1883, p. 5.

- ↑ "Small Change," Milan (TN) Exchange, 26 February 1880, p. 5.

- ↑ Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (M. Curlander, 1884), pp. 203-217.

- ↑ The Resignation of Assistant Attorney General Freeman," Washington Evening Star, 23 April 1881, p. 1.

- ↑ "Tennessee Republicans," Cincinnati Daily Star, 6 May 1880, p. 1.

- ↑ "Against Mason's Pardon," National Republican, 25 March 1882, p. 5.

- ↑ "A New Law Firm," Washington Evening Star, 1 May 1885, p. 4.

- ↑ "City and County," Socorro (NM) Chieftain, 11 December 1891, p. 4.

- ↑ Jerry K. Cline, Born and Raised: An American Story of Adoption (Xlibris Corporation, 2010), pp. 82-83.

- ↑ "Judge A.A. Freeman," Old Abe Eagle, 28 February 1895, p. 1.

- ↑ William A. Keleher, Memoirs, Episodes in New Mexico History, 1892-1969 (Sunstone Press, 2008), p. 179.

- ↑ "Verdict of Not Guilty," Eddy (NM) Current, 2 April 1898, p. 5.

- ↑ Charles Whately Parker and Barnet M. Greene, "James Oscar Cameron," Who's Who in Canada, Vol. 15 (International Press Limited, 1912), p. 590.

- ↑ Directory of Directors in Canada, 1912, p. 41. Retrieved: 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "1261 Richardson Street," Victoria Heritage Foundation website. Retrieved: 5 July 2014.