Anidolic lighting

Anidolic lighting systems use anidolic or nonimaging optical components (typically parabolic or elliptical mirrors) to capture exterior sunlight and direct it deeply into rooms, while also scattering rays to avoid glare. Anidolic, or non-imaging, mirrors are traditionally used in industrial solar concentrators. Light captured and narrowed by these mirrors in daylighting applications does not converge into a single focal point; the system is unable to form an image of the light source and is thus called non-imaging, or anidolic[1] (from Greek an: without, eidolon:image).[2] The same concept has been tested for interior lighting applications; they attempt at solving the most challenging objective – effective capture and redistribution of light on cloudy, overcast days.[2]

Design of anidolic lighting systems breaks down to three critical parts:

- zenithal light collector for capturing daylight;

- optimal collection and distribution of captured light to target areas (anidolic ceilings, light tubes etc.);

- optimal integration into the building facade.[2]

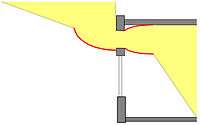

Typically, light is captured with a compound parabolic collector (CPC) or elliptical collector (CEC) mounted on the exterior wall. These mirrors provide a wide and even collection pattern, with vertical capture angle approaching 90 degrees, from the horizon to the vertical plane of the supporting wall. Unlike industrial parabolic troughs, architectural CPC does not concentrate captured light into a single focal point or focal line (which creates a fire hazard); instead, light is directed into the building through a relatively wide opening. Even capture pattern, correlating with low concentration ratio, alleviates the need for a solar tracker: a permanently fixed anidolic collector remains effective at any time of day.[3] A second CPC or CEC acting as an angle transformer[4] disperses this beam into a wide-angle, diffused pattern.

Reference external CPC for a 6 metre deep room protrudes 0.67 metres from the exterior wall and employs a 3.6 metre long, 0.5 meter tall light tube, followed with a 0.9 metre long interior CPC, to deliver captured light into the back of the room (with wide external CPC, light tube actually becomes a flat anidolic ceiling).[2] This arrangement provided 32% energy savings over a six-month period compared to a reference facade.[2]

External parabolic collectors require proper heat insulation, double-glazed windows over the zenithal opening and roller blinds to reduce excessive lighting, glare and heat on sunny days.[2] Integrated anidolic systems reduce external protrusion and attempt to visually blend into traditional facades, however, like all anidolic systems, they are susceptible to glare and offer no protection from overheating on sunny days.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Chaves, p. 72

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scartezzini, p. 14

- ↑ Chaves, p. 146

- ↑ See Chaves, pp.75, for a discussion on angle transformer properties.

- ↑ Scartezzini, p. 15

Sources

- Chaves, Julio (2015). Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1482206739.

- J.-L. Scartezzini (2003). "Advances in daylighting and artificial lighting". Research in Building Physics: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Building Physics, 14–18 September 2003, Antwerpen, Belgium. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-90-5809-565-7.