Bansuri

| |

| Other names | Murali, Bansi, Baashi, Baanhi |

|---|---|

| Classification | Indian Woodwind Instrument |

| Playing range | |

| 2.5 Octaves (six-hole), 3 Octaves (seven-hole) 3.5+ octaves(Sameer Flute) | |

| Related instruments | |

| Venu | |

| Musicians | |

| List of Indian Flautists | |

| More articles | |

| Hindustani classical music, Pannalal Ghosh, Hariprasad Chaurasia | |

The bansuri is a transverse flute of South Asia made from a single hollow shaft of bamboo with six or seven finger holes. An ancient musical instrument associated with cowherds and the pastoral tradition, it is intimately linked to the love story of Krishna and Radha and is also depicted in Buddhist paintings from around 100 CE. The Bansuri is revered as Lord Krishna's divine instrument and is often associated with Krishna's Rasa lila; mythological accounts tell of the tunes of Krishna's flute having a spellbinding and enthralling effect not only on the women of the Braj, but even on the animals of the region. The North Indian bansuri, typically about 14 inches in length, was traditionally used as a soprano instrument primarily for accompaniment in lighter compositions including film music. The bass variety (approximately 30", tonic E3 at A440Hz), pioneered by Pannalal Ghosh has now been indispensable in Hindustani Classical music for well over half a century. Bansuris range in size from less than 12" to nearly 40".

History

The word bansuri originates in the Sanskrit bans (बाँस) [bamboo] + sur (सुर) [melody]. There are two varieties of bansuri: transverse, and fipple. The fipple flute is usually played in folk music and is held at the lips like a whistle. Because it enables superior control, variations and embellishments, the transverse variety is preferred in Indian classical music.

Pannalal Ghosh (1911–1960) elevated the Bansuri from a "folk" instrument to the stage of what was then called "classical" music.[1] He experimented with the length, bore and number of holes, and found that longer length and larger bore allowed for better coverage of the lower octaves. He eventually pioneered longer bansuris with larger bores and a seventh hole placed a quarter turn inwards from the line of the other six finger holes.

A generation of musicians born in the 20's, probably inspired by the raise of bansuri playing initiated by Pannalal Ghosh, kept on developing and exploring the possibilities of the flute to render raga music. The work opportunity offered by the radio and the new institutions growing around North India encouraged many musicians to take on the flute to further its technique and styles. Among them were Raghunath Prasanna (c.1920–June 1999), a shehnai and flute player from Varanasi; Prakash Wadhera (1929–2005), a flute player and musical critic who joined the Gandharva Mahavidyalay as a teacher in Delhi; Vijay Raghav Rao (1925–), from Mumbai; and Devendra Murdeshwar (c.1923–2000).

Construction

Bansuri construction is a complex art. The bamboo suitable for making a bansuri needs to possess several qualities. It must be thin walled and straight with a uniform circular cross section and long internodes. Being a natural material, it is difficult to find bamboo shafts with all these characteristics, which in turn makes good bansuris rare and expensive. Suitable species of bamboo (such as Pseudostachyum) with these traits are endemic to the forests of Assam and Kerala.[2]

After harvesting a suitable specimen, the bamboo is seasoned to allow naturally present resins to strengthen it. Once ready, a cork stopper is inserted to block one end, next to which the blowing hole is burnt in. The holes must be burnt in with red hot skewers since drilling causes the fibrous bamboo to split along the length, rendering it useless. The approximate positions of the finger holes are calculated by measuring the bamboo shaft's inner and outer diameters and applying certain formulae. Flute makers have only one chance to burn the holes, and a single mistake ruins the flute, so they usually begin by burning in a small hole, after which they play the note and using a chromatic tuner and a drone called tanpura, gradually make adjustments by sanding the holes in small increments. Once all the holes are perfected, the bansuri is steeped in a solution of antiseptic oils, after which it is cleaned, dried and its ends are bound with silk or nylon threads for both decoration as well as protection against thermal expansion.

Playing

|

Sound samples

Bass Bansuri played with key of E(white three) sound samples

Small Bansuri played with key of E(white three) |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Indian music is played in 3 octaves—mandra (lower), madhya (middle), and taara (high) -- with ornamentations such as meendas (glides) and gamakas (oscillations).

Bansuris range in length from less than 12 inches (called muralis) up to about 40 inches (shankha bansuris). 20-inch bansuris are common. Another common and similar Indian flute played in South India is the venu, which is shorter in length and has 8 finger holes (this type of Indian flute is played by the Carnatic musician Shashank Subramanyam). The index, middle, and ring fingers of both hands are usually used to finger the six-hole bansuri. For the seven-hole bansuri, the little finger (pinky) of the lower hand is usually employed.[3]

As with other air-reed wind instruments, the sound of a bansuri is generated from resonance of the air column inside it. The length of this column is varied by closing or leaving open, a varying number of holes. Half-holing is employed to play flat or minor notes. The 'sa' (on the Indian sargam scale, or equivalent 'do' on the octave) note is obtained by covering the first three holes from the blowing-hole. Octaves are varied by manipulating one's embouchure and controlling the blowing strength. Various grip styles are used by flutists to suit different lengths of Bansuris, the two prominent styles being the Pannalal Ghosh grip, which uses the fingertips to close the holes, and the Hariprasad Chaurasia grip, which uses the pads (flat undersides) of the fingers to close the holes.[4] While playing, the sitting posture is also important in that one should be careful not to strain one's back over long hours of practice. The size of a Bansuri affects its pitch. Longer bansuris with a larger bore have a lower pitch and the slimmer and shorter ones sound higher.

In order to play the diatonic scale on a bansuri, one needs to find where the notes lie. For example, in a bansuri where Sa or the tonic is always played by closing the first three holes, is equivalent to C, one can play sheet music by creating a finger notation that corresponds to different notes. A flutist is able to perform complex facets of Raga music such as microtonal inflections, ornamentation, and glissando by varying the breath, performing fast and dextrous fingering, and closing/opening the holes with slow, sweeping gestures. These techniques are demonstrated by the famous Indian flautist Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia.

Care and maintenance

Since the bansuri is a natural woodwind instrument, it is prone to cracks and thermal stresses while playing.

- Avoid playing in very cold conditions. This causes the bamboo to expand unevenly and develop cracks, because of the warm air blown into it.

- Frequently oiling the bansuri is recommended as this conditions the bamboo and makes it to last longer. Usually, slight amount of mustard oil is used on the inside of the bansuri. Some bansuri players and makers prefer linseed oil or walnut oil to mustard oil, owing to its strong odour. Oiling must never be done on the threads or near the blowing hole on the inside. A small cotton swab (attached to any convenient piece of stick) soaked in the oil should be applied on the inside, about two inches away from the blowing hole. It must be made sure that the bansuri is cold (i.e., not recently played, because recently played bansuris have moisture on the bore surface) before oiling. After oiling is done, it is allowed to soak completely.

- The frequency of oiling depends on the climatic conditions in which the bansuri is played. Dry hot climates require oiling as frequent as four to six times a year.

- If, in case, cracks develop on the bansuri, they will most likely destroy the tuning of the bansuri. To prevent further damage due to cracks, apply instant glue (with lower viscosity, so that it can seep into the crack and bond it) on the crack and then bind the area with threads (nylon threads used in crochet can be used).

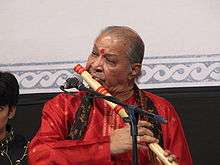

Veteran players

Well-known bansuri players include Pannalal Ghosh (1911–1960), Raghunath Prasanna (c. 1920 – 1999), Vijay Raghav Rao (born 1925), Bholanath Prasanna (1930–1996), Raghunath Seth (1931–2014), Hariprasad Chaurasia (born c. 1938), Nityanand Haldipur (born 1948), Rajendra Prasanna (born 1956), Ronu Majumdar (born 1963), Rupak Kulkarni (born 1968), Pandit Rohit Anand (born 1960), Pravin Godkhindi (born 1973), Sameer Inamdar (born 1987), and Steve Gorn (born 1944)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "the Legacy of Pandit Pannalal Ghosh". David Philipson, CalArts School of Music. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ "Bansuri Bamboo Flute". Brindavan Gurukul.

- ↑ Leifer, Lyon (2005). How to Play the Bansuri: A Manual for Self-Instruction Based on the Teaching of Devendra Murdeshwar. Rasa Music Co. ISBN 0-9766219-0-8.

- ↑ "The Right Grip". Prasad Bhandarkar, bansuriflute.com.

http://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/four-notches-above/ Sameer Inamdar

http://www.dnaindia.com/pune/report-fluting-his-way-to-the-limca-book-of-records-1762431