Bantayan Island

Bantigue shore (low tide) | |

.svg.png) Bantayan island Location within the Philippines | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Visayan Sea |

| Coordinates | 11°12′N 123°44′E / 11.2°N 123.73°ECoordinates: 11°12′N 123°44′E / 11.2°N 123.73°E |

| Archipelago | Philippines |

| Area | 110.71 km2 (42.75 sq mi)[1] excluding other islands |

| Length | 16 km (9.9 mi) |

| Width | 11 km (6.8 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Region | Central Visayas (Region VII) |

| Province | Cebu |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Bantayanon |

| Population | 125,726 (2015 census)[2] |

| Pop. density | 1,100 /km2 (2,800 /sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Official website |

www |

Bantayan Island is an island located in the Visayan Sea, Philippines. It is situated to the west of the northern end of Cebu island, across the Tañon Strait. According to the 2015 census, it has a population of 125,726.[2]

The island is administratively divided into three municipalities:

- Bantayan (the largest municipality, covering the central part)

- Madridejos (covering the northern portion)

- Santa Fe (covering the eastern portion)

The island area is 110.71 square kilometres (42.75 sq mi). The island is mostly covered with coconut palms; the elevation is mostly below 30 metres (100 ft), with only one taller hill, at 60 metres (200 ft), in barangay Atop-atop.

Geography

Island group

Bantayan is the main and largest island of the Bantayan island group that lies close to the geographical centre of the Philippine archipelago.

The island group includes numerous smaller islands (some uninhabited or uninhabitable), mostly around the southwest corner of the island. About 20 of these islets stretch for about 8 kilometres (5 miles) southwest from Bantayan municipality port area, with some nearer ones being accessible on foot from the main island at low tide. The islands are beside the busy shipping lanes for ships and ferries coming from Mindanao or Cebu City on their way to Manila. The islands are all small and green and low, virtually indistinguishable one from another.

Some of the more notable are:[lower-alpha 1]

- Botique (or Botigues, Batquis)

- Botong

- Byagayag Islands (Daku and Diot)

- Doong

- Hilantagaan (or Jicantangan, Jilantagaan, Cabalauan)

- Hilantagaan Diot (or Silion, Pulo Diyot (little island))

- Hilutungan (or Hilotongan, Lutungan)[lower-alpha 2]

- Lipayran

- Mambacayao (or Mambacayao Daku)

- Moambuc (or Maamboc, Moamboc, Kangka Abong, Cangcabong)

- Panangatan (or Pintagan)

- Panitugan (or Banitugan)

- Patao (or Polopolo)

- Sagasay (or Sagasa, Tagasa)

- Silagon

- Yao Islet (or Mambacayao Diot)

- 'These Bantayan islets are numerous, and are all low and very small.' —Juan de Medina (1630)

-

5 Hilantagaan Island seen from the Santa Fe–Hagnaya ferry (S)

-

6 Hilantagaan Dyot, brgy Hilantagaan, Santa Fe, seen from W.

-

7 Sunset over Hilutungan, seen from E.

-

13 Patao island (or Polopolo) off Patao, Bantayan

In addition, Guintacan Island (or Kinatarkan, Batbatan) to the NE is part of Santa Fe municipality although it is not part of the Bantayan islands group.

Demographics

|

25,000

50,000

75,000

100,000

125,000

150,000

1990

1995

2000

2007

2010

|

Santa Fe Madridejos Bantayan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Language

The Bantayanon language is mostly a mixture of different neighbouring Visayan languages: The principally native Cebuano (from Cebu and Eastern Negros) and Hiligaynon (from Western Negros and Iloilo), Boholano (from Bohol), Masbateño (from Masbate) and Waray-Waray (from Leyte and Samar). However it has its own words such as "kakyop" (yesterday), "sara" (today) and "buwas" (tomorrow).

Climate

| Bantayan Island Average temperature in Bantayan island is 28·0°C Humidity 75–85% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The climate is typically equatorial – temperature range over the year is less than three degrees Celsius (5.4 deg F), and annual rainfall exceeds 1,500 millimetres (59 in). January to April inclusive are less wet than the other months. This supports at least two rice crops per year. The climate in Bantayan falls within Coronas climate type IV, characterised by not very pronounced maximum rainfall with a short dry season from one to three months and a wet season of nine to ten months. The dry season starts in February and lasts through April sometimes extending to mid‑May.

Bantayan has a tropical climate. Most months of the year are marked by significant rainfall. The short dry season has little impact. This location is classified as Am (Tropical monsoon climate) by Köppen–Geiger climate classification system.

Geology

Like most of Cebu province,[9] the lithology of the island consists of two unit types:

- the Plio-Pleistocene Carcar Formation

Carcar formation is typically a porous coralline limestone characterized by small sinkholes, pitted grooves, and branching pinnacles.[10] This suggests in situ deposition. Its dominant composition are shell, algae, and other carbonate materials, while macro and micro fossils are found abundant in its formation. - quaternary alluvium (the youngest lithologic unit)

Alluvium is mostly found in coastal areas. Calcareous sand derived from the weathering of limestone mostly makes up the tidal flat. This appears as fine to coarse-grained sand mixed with shell fragments.

As a consequence of the geology, water supplies are hard.

National protected areas

Uncultivated Vanda coerulea

Bantayan and its surrounding islands have been included in several pieces of legislation giving protected status.

- Wilderness area

In 1981 President Marcos signed proclamation no. 2151 giving certain parts of the country protected status.[3] This included Bantayan Island with the status of a "Wilderness Area",[lower-alpha 3] although its physical extent was undefined, albeit the proclamation described all the areas named as "containing an aggregate area of 4,326 hectares, more or less". Eleven years later the Philippine Congress passed Republic Act 7586 – the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) Act of 1992, managed by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) – which reaffirmed the protected status.[4] However it too did not specify the extent of Bantayan Island Wilderness Area (BIWA), which is therefore taken to include the whole island group, more than 11,000 hectares.[lower-alpha 4]

After 2013's Typhoon Yolanda, there has naturally been a need and desire for reconstruction, however one major problem is that because of the designation, there is little land titling, and international relief organisations (and others) are reluctant to fund construction on land where title does not exist.[11] 2014 has seen the start of initiatives to define the area, and to devise a general plan for its management (BIWA-GMP). That plan recommends retaining only 596.41 ha (1,473.8 acres) as strictly protected wildlife reserves, or 4.8% of the original BIWA, and allowing multi-use zoning of 10,648.27 ha (26,312.4 acres).[lower-alpha 4] From that has arisen a more concrete proposal regarding reclassification.[12] Now the plan is to be recommended to Congress.[13]

- Tourist zone and marine reserve

Presidential proclamation no. 1801 of 1978 established Tourist zones and marine reserves, and placed the island of Hilutungan within its scope.[6]

- Protected seascape

The Tañon Strait protected seascape was established by President Ramos under proclamation no. 1234 of 1998.[14] This includes more than (29,187 m (29 km; 18 mi)) of the eastern shoreline of Bantayan island. In February 2015, 17 years after its declaration, the first summit on the Tañon Strait protected seascape is to be held.[15]

Agriculture

The dominant uncultivated vegetation is ipil-ipil (Leucaena leucocephala). Cultivated crops include coconut, cassava, banana, sugarcane, corn and mango.

The principal cash crops are:[lower-alpha 5]

| Plant | Area (ha) | Yield | Coconuts on the palm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 400 | 775 tonnes (763 tons) | |

| Mango | 47.53 (1214 trees) | 455 tonnes (448 tons) | |

| Chico | 23 | n/a | |

| Coconut | 713 | n/a |

Fauna

The common wolf snake can occasionally be found on the island.

Avifauna

The following list shows birds whose presence has been verified.[17][18]

Striated heron (Butorides striata) |

• | Eastern reef-egret (Pacific reef-egret) | Egretta sacra [lower-alpha 6] |

| • | Chinese egret | Egretta eulophotes [lower-alpha 7] | |

| • | Little heron (striated heron) | Butorides striata [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Grey plover | Pluvialis squatarola [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Greater sand-plover | Charadrius leschenaultii [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Whimbrel | Numenius phaeopus [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Ruddy turnstone | Arenaria interpres [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Godwit sp | Limosa sp [lower-alpha 8] | |

Pied harrier Circus melanoleucos |

• | Lesser frigatebird | Fregata ariel [lower-alpha 6] |

| • | Pied harrier | Circus melanoleucos [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Black-chinned fruit dove | Ptilinopus leclancheri [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Island collared dove | Streptopelia bitorquata [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | Island swiftlet | Collocalia vanikorensis [lower-alpha 6] | |

| • | White-collared kingfisher | Halcyon chloris [lower-alpha 6] |

The sea

The coast of Bantayan and its islands mostly alternates between mangal and palm trees. Because of the shallow slope on the shelf, the intertidal area can be quite extended, leading to rocky and muddy shallows at low tide. This means that places with a sandy shore – a beach – are infrequent. Good beaches can be found in the southeast around Santa Fe, and in the northwest at Patao and Madridejos. Even these though are not cleaned, and depending on the currents there can be considerable amounts of flotsam and jetsam on the beach and in the sea.

Coral

Of the approximately 500 varieties of coral known worldwide, about 400 are found in the Philippines.[19] However their future is seriously threatened – mainly due to destructive fishing techniques, such as blast fishing and cyanide fishing, which indiscriminately destroy much of the ecosystem, including the coral reefs. In addition, global warming and ocean acidification also contribute significantly to worldwide loss. Globally coral sees 50%–70% threatened or lost; southeast Asian coral reefs are in even worse condition, and it is estimated in the Philippines the figure under threat is greater than 90%, with less than 1% in good condition. Until now proper compliance of international laws has been poor,[20] although it is starting to be taken seriously. Meanwhile, other efforts are under way in Bantayan to accelerate the regrowth, using coral farms.[21]

Starfish

There are many starfish to be seen in the intertidal area. Their detrivorous diet helps keep the water clean. Further out though, the crown-of-thorns starfish is a considerable threat to the coral reef, because of its voracious hunger for the coral.

Mangal

Mangroves are salt-tolerant, woody, seed-bearing plants that are found in tropical and subtropical areas where they are subject to periodic tidal inundation.[22] The Philippines has over 40 species of mangroves and is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world as there are only about 70 species of mangroves worldwide. The mangrove ecosystem is a very diverse one and is home to many birds, fish, mammals, crustaceans and other animals.

Mangroves provide an important nursery for fish, shellfish and other organisms. It is estimated that each hectare of mangrove can provide food for 1,000 kg of marine organisms (890 lb/acre). With this abundance of food for fish present in the mangroves, each hectare of mangal yields 283.5 metric tons of fish per year (112.9 long ton/acre). Mangroves also provide other important functions such as preventing soil erosion and protecting shoreline from typhoons and strong waves. Mangroves provide many other products and services such as medicines, alcohol, housing materials and are an area for research and tourism.

However even with all of these known benefits the state of mangroves within the Philippines is very dim. In the early 1900s there were approximately 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) of mangroves but today there are only about 1,200 km2 (460 sq mi). Many of the mangrove areas were destroyed to make way for fishponds and reclamation areas. They were used indiscriminately for housing – both building materials and reclamation – and were disturbed by siltation and pollution.

Now that the true benefit of these ecosystems is known there is protection and rehabilitation of these important ecosystems. It is now illegal to cut down mangroves for any purpose and local governments and community organizations have taken active roles in planting and managing mangrove plantations. There is hope that in the future mangroves will return to the healthy status that they once held.

History

Early origins

There are almost no physical records nor evidence to indicate when the first people came to Bantayan, nor their places of origin. Some believe they can be traced back to Panay, others believe that the bulk of them were of Cebuano origin, and still others say they came from Leyte and Bohol.

Connections between Bantayan and other places can be deduced from the mixed dialects spoken by the people, and their ancient culture such as cloth‑weaving, dance, and architecture. In addition certain old-established Hispanic family names are associated with certain locations:

- Panay

-

- Rubio

- Arcenaz

- Alvarez

- Sevilleno

-

- Cebu

-

- Rodriguez

- Ancaja

- Mansueto

- Villacruz

-

- Leyte

-

- Villacin

- Villaflor

- Otega

- Carabio

-

- Bohol

-

- Hubahib

- Garcia

- Caquilla

-

- Panay

There is little documentary evidence of life and culture before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores. What we know of them is gathered from handed-down accounts and folklore.

The early people were said to be timid. They didn’t travel and knew little of places away from their homes. They wore little clothing because the climate didn’t need it. The abundance of fish, wild games, wild fruits and tuber, such as ba-ay, hagmang,[lower-alpha 9] bailacog, and kiot, made the people do little more than make clearings on which to plant corn, camote (sweet potato) and other vegetables. Large and small trees grew and spread, shading the ground all year round with their heavy foliage. Vines and creepers climbed the trees hanging from bough to bough; cultivation of open land was difficult.

The Spanish period

Early years

During the period 1565–1898 the Philippines was a Spanish colony, part of the Spanish East Indies.

The parish church was established in 1580 – as an encomienda of the heir of Don Pedro de Gamboa.

Writing in 1582, Miguel de Loarca stated:[23]

ysla de bantayan A la vanda del norte de a ysla de çubu apartada della como dos leguas esta la ysla de bantayan que terna oçho leguas de box y dos de ançho tiene çerca de mil yndios y son de vn encomendero ella y la ysla de Vohol[lower-alpha 10] aRiba diçho, la gente della es buena gente tratante tienen grande pesquerias que es ysla de heçha muçhos baxos tiene pesqueria de perlas aunqe poca cosa no se coje en ella sino a Millo y borona y no se coje ningun arroz por ques tierra toda de mal pais aunque llana algunos de los naturales desta ysla haçen sus sementeras en la ysla de çubu, como digo esta dos leguas de trauesia tiene muy buenos palmares y lo mismo se a de entender de todas las yslas de los pintados porque todas lellas abundan en gran cantidad de palmas—Island of Bantayan. About two leagues[lower-alpha 11] north of the island of Çubu lies the island of Bantayan. It is about eight leagues in circumference and two leagues wide, and has a population of about one thousand Indians; this and the above-mentioned island of Vohol[lower-alpha 10] are under the charge of one encomendero. Its inhabitants are well-disposed. They have large fisheries, for there are many shoals near the island. There is also a pearl-fishery, although a very small one. The land produces millet and borona, but no rice, for all the island has poor soil notwithstanding that it is level. Some of the natives of this island cultivate land on the island of Çubu, which, as I have said, is two leagues away. The island abounds in excellent palm-trees — a growth common to all the Pintados islands, for all of them abound in palms.

He also wrote:[24]

Otra manera de esclauonia. Ay otro genero de señorio qe yntroduxo Vno que se llamaua sidumaguer qe Diçen que a mas de dos mill años qe fue que porque le quebraron vn barangay en languiguey donde el era natural ques En la ysla de bantayan qe si tenian los qe defienden, de Aquellos qe le quebraron el barangay si qdo mueren dexan diez esclauos le dauan dos y Al Respeto toda la demas haçienda, y esta manera de esclauonia. quedo yntroduçida en todos los yndios de las playas y no los tinguianes.Another kind of slavery. There is another kind of lordship which was first introduced by a man whom they call Sidumaguer — which, they say, occurred more than two thousand years ago. Because some men broke a barangay[lower-alpha 12] belonging to him — in Languiguey, his native village, situated in the island of Bantayan — he compelled the descendants of those who had broken his barangay to bequeath to him at their deaths two slaves out of every ten, and the same portion of all their other property. This kind of slavery gradually made its way among all the Indians living on the coast, but not among the Tinguianes.

Writing in 1588, Domingo de Salazar reported:[25] "The island of Bantayan is small and densely populated. It has more than eight hundred tributarios, most of them Christians. The Augustinians who had them in charge have abandoned them also, and they are now without instruction. This island is twenty leagues from Zubu."

Some time in 1591, Bantayan's population totalled 683 tributes representing 6732 persons.[26]

Writing in 1630, Fray Juan de Medina noted:[lower-alpha 13]

Religious were established in the island of Bantayan, located between the island of Panay and that of Sugbú,[lower-alpha 14] but farther from that of Panay. However, if one wishes to go to the island of Sugbú without sailing in the open sea, he may coast from islet to islet, although the distance across is not greater than one or one and one-half leguas.[lower-alpha 11] These Bantayan islets are numerous, and are all low and very small. The largest is the above-named one. When Ours acquired it, it had many inhabitants, all of very pleasing appearance, and tall and well-built. But now it is almost depopulated by the ceaseless invasions from Mindanao and Jológ.

He goes on to say: "This island has a village called Hilingigay, which it is said was the source of all the Bisayan Indians who have peopled these shores, and whose language resembles that of Hilingigay."

Derivation of name

During the time of 22nd Governor-General Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera,[lower-alpha 15] the Visayans were continually harassed by Moro pirates who came on raids to capture slaves. Consequently, tall stone walls and watchtowers were built in different parts of the archipelago, for refuge and protection from Moro aggression.

Popular folklore says that these watchtowers were known locally as "Bantayan sa Hari", meaning "Watchtowers of the King", and they served as lookout towers for incoming vintas (Moro pirate vessels). In the course of their vigil, it became common to say, "Bantayan! Bantayan!", meaning, "Keep watch! Keep watch!", and that was how this island-group got its name.

In all there were 18 watchtowers built on the Bantayan islands. Most have not survived, although relics can be seen to this day.[lower-alpha 16]

That at Madridejos is in fair condition, that at Santa Fe less so. There is a particularly fine example on Doong island.[27]

In his "Statement of the Annual Incomes and Sources of Profit of His Majesty in These Philipinas Islands" for the year 1608, Pedro de Caldierva de Mariaca declares the tributes (tax) from Bantayan and Bohol combined amount to 2400 gold pesos.[28][lower-alpha 17]

Industry

Don José Basco y Vargas was Governor-General of the Philippines from July 1778 until September 1787. During his period in office, he pioneered many projects for the encouragement of agriculture and industries. However many small industries in the islands were completely abandoned because the people were forced to work on building roads, public buildings and churches. Those enforcing were called politas.[lower-alpha 18]

The abundance of fish, favourable climate and virgin soil then greatly determined the occupation of the people. These geographical factors became strong stimuli for the people to be fishermen, farmers and sailors. Much later, the small clearings were expanded to fields.

The old Spanish roads connecting Santa Fe, Bantayan, and Madridejos were constructed chiefly through the services of labour and partly supported by the tribute funds.

Religion

When the Spaniards came to Bantayan, the people already had some form of religious convictions and worship, such as animism, shamanism, evocation and magic. They easily conceived the idea of evil spirits, good spirits, witches and ghosts. In order to please these imaginary creatures people often resorted to charms, vows, sacrifices and self-harm. It was a common belief among the illiterate people of the past that cholera and other fatal diseases were caused by poison which an evil spirit had put into the wells and that the people could be saved from the dreaded disease only by chanting prayer and holding processions.[29][30]

The cooperation between the church and the state did not last very long. Quarrels between the church and the state ensued. There was struggle for political power, from the Governor-General down to the alcalde mayors on one hand and from the archbishop to the friars on the other. Because of this, projects for improvements were all paralysed.

The American period

On 4 January 1899, following the defeat of Spain in the Spanish–American War, a new government was born to the Philippines. With instructions from President McKinley, General Otis who commanded the US Army in the Philippines declared that the American sovereignty must be recognized without condition. This was the beginning of the American period.

This island-group did not taken any active part in the revolution against Spain or America. However, after the Filipino–American War,[31] a reactionary group was organized, headed by Patorete of Santa Fe, then still a barrio of Bantayan. Their announced purpose was to resist the invaders, but the armed goons carried a campaign of terror burning the northern part of Santa Fe, plundering and forcing Capitan Miroy and Aguido Batabalonos to join them. This resulted in great fear and tension among the inhabitants.

The condition of the barrios, after the overthrow and immediately preceding the arrival of the Americans, in general, was very far from satisfactory. Sanitation was entirely a stranger; barrio life was dreadful. There were few signs of improvement among the people since their primitive ancestors.

The subdivision of the province of Cebu was developed utilizing the method introduced by Spain. A new provincial law had been enacted in 1895 and necessary appointments were then made. At that time, Bantayan was already organized as pueblo. Santa Fe was organized as such in 1911 and Madridejos in 1917. These pueblos were given a new corporate form under the Municipal Council chosen by a limited native electorate. For the local head of the administration, the title Presidente took the place of the former Gobernadorcillo or Capitan[lower-alpha 19]

Committed to the task of administering the newly organized municipal governments were the first presidentes of the three towns comprising the island-group namely: Gregorio Escario for Bantayan, Vicente Bacolod for Madridejos and Casimiro Batiancila for Santa Fe. Political parties were formally organized since the early days of the American regime. Partido Liberal came towards the end of 1900. Pascual Poblete founded the Partido Independista in 1902.

During the administration of Governor-General Luke E. Wright (1904–1906), the public road policy was inaugurated. Little by little the stage trails were changed to roads of more durable construction. Late in 1913 the construction of Santa Fe—Bantayan road began and in 1918 the Bantayan—Madridejos road followed; both were completed in 1924.

Then and now, fishing and farming were important industries of the people, but from the year 1903 to 1925, weaving of piña cloth and the gathering of maguey (agave) fibre were very lucrative pursuits of the people. Over the years demand for these products weakened and died out. At about the same, hand embroidery termed as "spare time industry" came in. A good number of women adopted it and were actively engaged in it for some years. The local output was quite significant. In 1923, because of weak and unsettled market conditions, particularly in Manila, the business gradually disappeared.

Independent Philippines

Gregorio Zaide described the Philippine national characteristic as "pliant, like bamboo, bending in the wind without breaking".[32] This might explain the war-time actions of the then mayor Isidro Escario, who had himself rowed out to meet a fleet of Japanese warships where he treated with them: Bantayan was not invaded and the war basically passed it by.[lower-alpha 20]

Economy

Commerce

Bantayan islands are considered Cebu’s fishing ground from where boatloads of fish – guinamos (salted fish) and buwad (dried fish) – are transported daily to Cebu and Negros for consumption and further distribution to as far as Mindanao and Manila. Equally important is the thriving poultry industry with hundreds of thousands of chicken eggs produced daily.

Years ago, poultry raising was mainly a backyard affair. Today it has grown into a large scale and highly specialized industry. Big poultry farms are located near the national and feeder roads. In excess of one million chickens are kept in yards and specially constructed barns with more than half a million eggs gathered every day. These eggs are exported to Cebu, Manila, and Mindanao and other towns and cities in the Visayas. This industry, along with copra making, tubâ gathering and fishing, has helped Bantayan solve its unemployment problem.

Transport

The island can be reached via ferry services from Hagnaya (San Remigio) to Santa Fe, and from Estancia, Iloilo and Sagay to Bantayan municipal port. Bantayan Airport handles infrequent flights from chartered planes usually arriving from Mactan‑Cebu International Airport.

Goods are shipped through Bantayan municipal port. There is also a small dock in brgy Baigad capable of handling small pumpboats. However it is in a very poor state of repair, and hasn't handled any vessel since 2007.

There are three lightstations around the islands:[lower-alpha 21]

- ⛯ LS Bantayan: just offshore of brgy Bantigue

- ⛯ LS Buntay: offshore of the Kota promontory, Madridejos

- ⛯ LS Guintacan: at the south end of the Guintacan island

Society

Health care

In view of the relatively high population of the island, and its growing popularity as a tourist spot, a bill has already been presented in Congress for the establishment of a 100‑bed tertiary‑level hospital.[34][35] Currently the nearest available tertiary care is in Cebu City, four hours travel by land and sea. Even the level‑1 facility available in Bogo takes at least 1½ hours travel.

Education

The first school in Bantayan, called the "Gabaldon School", opened in 1915.[36][37][38][39]

Public high schools on Bantayan are located in the municipalities of Bantayan, Santa Fe and Madridejos as well as on Doong island. There are also private high schools and tertiary colleges such as Bantayan Southern Institute and Salazar College. St Paul Academy (SPA) is a private high school in Bantayan municipality.

Sport

As is common through the Philippines, 'sport' is synonymous with cockfighting. It is an unusual sport in that the winner dies as well as the loser. Large sums are bet on the outcome of a fight, which usually lasts little more than one minute.

The birds themselves can look magnificent for their few brief moments of stardom, with purple-black plumage and a gold ruff.

There are several sports centres (cockpits) on the island. Smaller puroks just have an open-air arena.

Notable dates

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1580 | The Augustinians established the Parish of Bantayan as a convent under the patronage of La Asuncion de Nuestra Señora (The Ascension of Our Lady), a mission-station of the friars in the Visayas and thus the first parish in Cebu province and one of the few parishes still in existence outside Mexico which were once a part of the Archdiocese of Mexico. |

| 1603 | The Augustinians relinquished the administration of the church to the secular clergy. During the time of Bishop Pedro de Arce, Daan Bantayan (also Daanbantayan) and the nearby villages located in northern Cebu were placed under the administration of the parish,[lower-alpha 22] followed by the island of Maripipi. |

| 1628 | The biggest Moro attack took place when a fleet of vintas attacked, killing or abducting more than 800 natives mostly from the village of Hilingigay, now barangay Suba, and burning down the church.[lower-alpha 23] Juan de Medina wrote that the priest and a few Spanish residents tried to defend but had to run and hide after running out of ammunition.[41] |

| 1754 | Moro raid left the church and community in ashes. |

| 1778 | The old Spanish roads linking Santa Fe, Bantayan and Madridejos were constructed through forced labour.[lower-alpha 18] |

| 1790–1796 | Severe famine after crop failure. Not even a grain of corn could be had but the people subsisted upon amorseko (crab grass) which continuously grew on the walls of their nipa huts.[42][43] |

| 1860 | The first casa real was constructed (now Municipal Hall). |

| 1864 | Following the Education Decree of 1863,[44] the first Spanish school (for boys) was established under the direct supervision of the curate where religious instruction was instilled.[45][46] |

| 1880–1890 | Smallpox epidemic devastated the island |

| 1894 | The entire barrio of Ticad was razed to the ground by fire. Only the stumps of the posts could be seen above the ground. |

| 1902–1903 | Cholera epidemic.[lower-alpha 24] |

| 1905 |

|

| 1906 | The first bicycle came to Bantayan, owned by Leon Villacrusis. It was imported from Manila. The first bicycle imported from Japan was owned by Dr. Mabugat.[lower-alpha 25] |

| 1908 | Smallpox epidemic, eventually controlled by complete vaccination. |

| 1910 | The first motorized boat, MV Carmela, was owned by Yap Tico.[lower-alpha 26] It served the Bantayan–Cebu route. It also brought merchandise to and from Bantayan until it was destroyed by the typhoon of 1912. |

| 1912 | Typhoon, which took hundreds of lives in addition to work animals and agricultural crops that were destroyed.[49] |

| 1913 | Construction of the present Bantayan–Santa Fe road began. |

| 1915 | As a result of Public Act 1801, [lower-alpha 27] the main building of Bantayan Central School was built.[51] |

| 1918 | Construction of the Bantayan–Madridejos road began. |

| 1923 | The first car came to Bantayan island – a second-hand Dodge owned by Kapitan Casimiro Batiancila of Santa Fe. |

| 1924 | The whole road construction project linking Santa Fe, Bantayan and Madridejos ended. |

| 1927 | Bantayan Postal Office was opened within the municipal building. |

| 1930 | Cholera epidemic |

| 1935 | Beer was first distributed in Bantayan. |

| 1961 | Oil explorers came to Bantayan to dig the first oil well somewhere within Patao and Kabac.[52](rows 207 ff) |

| 1968 |

|

| 1973 | Fire broke out which destroyed almost the whole section of Suba, razed the entire public market and rendered more than 700 families homeless. |

| 1978 | Death of Isidro R. Escario, who had been mayor of Bantayan since 1937 apart from the war. His funeral procession and wake drew thousands: people were seen queueing one kilometre away from the wake. |

| 1981 | Presidential decree nominates Bantayan as a National Protected Area: Wilderness area.[3] |

| 1997 | Death of Antonio Ilustrisimo (born Bantayan 1904). He was a Master of Kali Ilustrisimo – his own development of the eskrima he learned from his father.[54][55] |

| 1999 | Overloaded ferry MV Asia South Korea en route Cebu–Iloilo City strikes submerged rocks about 8 nautical miles (15 km; 9 mi) west of Bantayan island and sinks in heavy seas with loss of 56 lives.[56][lower-alpha 29] |

| 2010 | Lipayran island hit by tornado - 15 shanties destroyed and seven damaged.[57] |

| 2013 | Class‑5 Super Typhoon Haiyan, within Philippines known as Yolanda, caused considerable damage to the entire island, but with relatively little loss of life.[lower-alpha 30] |

Notes

- ↑ Islands have several names, according to speaker's language. First name shown is as it appears on the NAMRIA topographical map.[5] Some of the smallest islands are not named on map.

- ↑ Declared a "Tourist Zone and Marine Reserve under the administration and control of the Philippine Tourism Authority" by Presidential Proclamation 1801 of 1978 [6]

- ↑ Wilderness area is a protected area that is created and managed mainly for purposes of research or for the protection of large, unspoiled areas of wilderness, whose primary purpose is the preservation of biodiversity and as essential reference areas for scientific work and environmental monitoring.

- 1 2 The total area of BIWA [11,244.5 ha (27,785.8 acres)] includes coastal areas below the high water mark, as well as other islands.

- ↑ 2001 data [16]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

- Conservation status: Least Concern

- ↑

- Conservation status: Vulnerable

- ↑

- Conservation status: Near Threatened

- ↑ wild yam having long edible tubers and thorny vines

- 1 2 Bohol

- 1 2 The league (legua) was not well defined, but was about 4 nautical miles (4.6 miles; 7.4 kilometres) ± 5%

- ↑ barangay here in its original meaning, a large boat

- ↑ de Medina 1630 full translation into English in Blair & Robertson (Vol 23, pp. 259–260) (and Blair & Robertson (Vol 24), which does not mention Bantayan.)

- ↑ Sugbú = Cebu

- ↑ In office June 1635 – August 1644

- ↑ Construction of watchtowers was not limited to Bantayan Island. Watchtowers were built in many locations in Cebu vulnerable to Moro raids, as well as in other parts of the Visayas, such as Southern Leyte, Northern Samar and Bohol. See for example:

Mandaue

Mandaue - ↑ A gold peso weighed 1 Troy ounce (1.1 oz; 31.1 g) so at 2012 prices (1 oz T gold ≈ $1750) that makes the tribute about $4.2 mn. See also Blair & Robertson Vol 03, p. 177

- 1 2 As well as paying tribute, all male Filipinos from 18 to 50 were obliged to render forced labour called polo, for 40 days of the year, reduced in 1884 to 15 days. It took various forms, such as building of roads and bridges; construction of public buildings and churches; cutting timber in forests; working in shipyards; and serving in Spanish military expeditions. A person who rendered polo was called a polista. The members of the principalia were exempt from polo: in addition rich Filipinos could pay a falla to avoid forced labour – about seven pesos annually. Local officials (former and current governadorcillos, cabezas de barangay etc.) and schoolteachers were exempt by law because of their service to the state. Thus the only ones who rendered forced labour were those poor Filipinos lacking social, economic or political prestige in the community. This served to reinforce notions of the indignity of labour in the minds of the Hispanicised Filipinos: labour became the badge of plebeianism.

- ↑ During the Spanish administration, each pueblo was under an Administrador Civil styled Gobernadorcillo (later Capitan Municipal), assisted by a Teniente Mayor, a Teniente Segundo, a Teniente Tercero, a Teniente del Barrio and a Cabeza de Barangay

- ↑ Similar collaboration by Emilio Aguinaldo saw him imprisoned after the war.

- ↑

.svg.png) LS Bantayan

LS Bantayan.svg.png) LS Buntay

LS Buntay.svg.png) LS GuintacanLightstations ⛯ around Bantayan island[33]

LS GuintacanLightstations ⛯ around Bantayan island[33]- ⛯ LS Bantayan

- ⛯ LS Buntay

- ⛯ LS Guintacan

- ↑ The town plan of Daanbantayan somewhat echoes the butterfly shape of Bantayan Island itself

- ↑ "Accordingly, in the past year of 1600 they came with a fleet of many vessels to the Pintados provinces, which are subject to your Majesty; and in the region known as Bantayan they burned the village and the church, killed many, and took captive more than eight hundred persons"[40]

- ↑ The 1902–1904 cholera epidemic claimed 200,000 lives in the Philippines.[47]

- ↑ The Mabugat family at that time substantially owned Mambacayao Island

- ↑

Yap Tico was a Chinese-owned trading company based in Manila. Although its nominal principal business was the import of rice, as an insurance company and general financial agency it featured in many civil law suits, most notably throughout the 1910s and 1920s, some of which set case law precedents, Lizarraga Hermanos vs. Yap Tico for example.[48]F. M. Yap Tico & Co. Ltd. Headquarters Manila, Philippines Key peopleLim Tuan (manager) Services - Importer of rice

- Insurance agent

Website www .bantayan .gov .ph - ↑ popularly known as the Gabaldon Act after its original author, Assemblyman Isauro Gabaldon.[50]

- ↑ The eye of the storm passed directly overhead around 0:00am on 24 November 1968. It didn't become a real Class‑1 typhoon until two days later.[53]

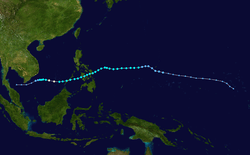

Track of Typhoon Nina (Seniang)

Track of Typhoon Nina (Seniang) - ↑

- ↑ Eye of storm passed overhead around midnight of 7 November 2013. At that time wind speeds were reaching 160 knots (300 km/h; 82 m/s; 180 mph).[58]

Track of Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan)

Track of Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan)

References

- ↑ Philippines 2012 Municipality Statistics Archived 8 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Census of Population (2015): Highlights of the Philippine Population 2015 Census of Population (Report). PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 permanent dead link] Presidential Proclamation No. 2151 (s.1981) of 29 December 1981 Declaring certain islands and/or parts of the country as Wilderness Areas.. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- 1 2 Republic Act No. 7586 of 1 June 1992 An act providing for the establishment and management of National Integrated Protected Areas System, defining its scope and coverage and for other purposes. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ NAMRIA 1995.

- 1 2 Presidential Proclamation No. 1801 (s.1978) of 10 November 1978 Declaring certain islands, coves and peninsulas in the Philippines as tourist zones and marine reserve under the administration and control of the Philippine Tourism Authority. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ↑ Census of Population and Housing (2010): Population and Annual Growth Rates for The Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities (PDF) (Report). NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ Census of Population (1995, 2000 and 2007): Population and Annual Growth Rates by Province, City and Municipality (Report). NSO. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012.

- ↑ Del Rosario, Pastor & Malapitan 2005.

- ↑ Hillmer & Scholz 1986.

- ↑ The Freeman 2014a.

- ↑ The Freeman 2014b.

- ↑ The Freeman 2014c.

- ↑ Presidential Proclamation No. 1234 (s. 1998) of 27 May 1998 Declaring the Tañon Strait situated in the provinces of Cebu, Negros Occidental and Negros Oriental as a protected area pursuant to RA 7586 (NIPAS Act of 1992) and shall be known as Tañon Strait Protected Seascape. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ The Freeman 2015a.

- ↑ "Municipality of Bantayan published figures".

- ↑ Taxonomic list of confirmed sightings (Spreadsheet (XL)), Wild Bird Club of the Philippines, 21 January 2004

- ↑ Robson 2011.

- ↑ Philippine Daily Inquirer 2005.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle 2002.

- ↑ The Manila Bulletin 2009.

- ↑ Mangrove Action Project

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 05, p. 48.

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 05, p. 140.

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 07, p. 41.

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 08, p. 132.

- ↑ Cabigas 2009.

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 14, p. 246.

- ↑ Zaide 1937.

- ↑ Zaide 1957.

- ↑ Filipino–American War 1899–1902

- ↑ Zaide 1968.

- ↑ "Coast Guard District Central Visayas Lightstations".

- ↑ The Freeman 2014f.

- ↑ ["Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2014-12-09. House Bill No. HB04802] of 12 August 2014 An act establishing the Bantayan Island National Hospital in the municipality of Bantayan, Province of Cebu and appropriating funds therefor. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ Aldana 1949.

- ↑ Catapang 1926.

- ↑ Fresnoza 1950.

- ↑ Isidro y Santos 1949.

- ↑ Blair & Robertson Vol 08, pp. 235–238.

- ↑ de Medina 1630.

- ↑ Clayton et al. 2002

- ↑ Galinato, Moody & Piggin 1999

- ↑ Decree of 20 December 1863

- ↑ Alzona 1932.

- ↑ Bazaco OP 1939.

- ↑ Society of Philippine Health History 2004.

- ↑ Lizarraga Hermanos vs

. Yap Tico, 24 Phil . 504 (1913) - ↑ Adelaide Advertiser 1912.

- ↑ The Freeman 2010.

- ↑ Araneta 2006.

- ↑ [<cite%20class="citation%20web">"Archived%20copy".%20Archived%20from%20%20on%2025%20January%202010<span%20class="reference-accessdate">.%20Retrieved%20<span%20class="nowrap">2014-10-17.<span%20title="ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fen.wikipedia.org%3ABantayan+Island&rft.btitle=Archived+copy&rft.genre=unknown&rft_id=http%3A%2F%2Fwww2.doe.gov.ph%2FPECR2006%2FPetroleum%2520PECR%25202007%2FHistorical%2520Well%2520Data%2520per%2520Area%2520-%2520Basin.htm&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Abook"%20class="Z3988"><span%20style="display:none;"> List of drilled wells in basins for petroleum areas on offer]

- ↑ Unisys Weather Information Systems 1968.

- ↑ Wiley 1997.

- ↑ Diego & Rickets 2002.

- ↑ People's Daily 1999.

- ↑ Philippine Daily Inquirer 2010.

- ↑ Unisys Weather Information Systems 2013.

Sources

- Adelaide Advertiser (21 October 1912). "Typhoon in the Philippines – Heavy loss of life" (Digitised archive). Adelaide, South Australia: National Library of Australia. p. 9. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Aldana, Benigno V (1949). The Educational System of the Philippines. Manila: University Publishing Co. OCLC 8985344.

- Alzona, Encarnación (1932). A History of Education in the Philippines 1565–1930. Manila: University of the Philippines Press. OCLC 3149292.

- Araneta, Gemma Cruz (30 August 2006). "Gabaldon Schools and other Heritage School Buildings". Philippine National Heritage Watch. Heritage Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- Bazaco OP, Fr Evergisto (1939). History of Education in the Philippines – Spanish period 1565–1898. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press. OCLC 3961863.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 03 of 55 (1569–1576). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554247144. OCLC 769945702.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803. Volume 05 of 55 (1582–1583). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554259598. OCLC 769945704.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the beginning of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1905). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 07 of 55 (1588–1591). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554340470. OCLC 769944907.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 08 of 55 (1591–1593). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554340630. OCLC 769944908.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1904). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 11 of 55 (1599–1602). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554343952. OCLC 769945233.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1904). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 14 of 55 (1606–1609). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne; additional translations by Henry B. Lathrop, Robert W. Haight. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0554346076. OCLC 769945705.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1905). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 23 of 55 (1629–1630). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord Bourne;. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-1153716369. OCLC 769945716.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1905). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 24 of 55 (1630–1634). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE; additional translations by Rev T.C. Middleton and Robert W. Haight. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. OCLC 769945717.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- Cabigas, Estan (21 September 2009), Cebu's lonely sentinels of the sea (Photographic essay), langyaw.com, retrieved 12 February 2015

- Catapang, Rev Vincent R (1926). The Development of the Present Status of Education in the Philippine Islands. Boston: The Stratford Co. OCLC 2605052.

- Clayton, W Derek; Vorontsova, Maria S; Harman, Kehan T & Williamson, H (2002). "World Grass Species: Descriptions, Identification, and Information Retrieval" (Online database). GrassBase – The Online World Grass Flora. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

Dallwitz (1980); and Dallwitz, Paine and Zurcher should also be cited

- de Medina, Fray Juan (1630) [1893]. Historia de los sucesos de la orden de n. gran P. S. Agustin de estas islas Filipinas: desde que se descubrieron y se poblaron por los españoles, con las noticias memorables / compuesta por el venerable Fray Juan de Medina [History of the Augustinian Order in the Filipinas Islands] (scan) (in Spanish). Manila: Chofréy y Comp. OCLC 11769618.

Page numbers 487–488 used twice

- Del Rosario, R.A.; Pastor, M.S. & Malapitan, R.T. (April 2005). Controlled Source Magnetotelluric (CSMT) Survey of Malabuyoc Thermal Prospect, Malabuyoc/Alegria, Cebu, Philippine (PDF). World Geothermal Congress. Antalya, Turkey. p. 2 Figure 2: General Geology of Cebu Province. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Diego, Antonio & Rickets, Christopher (2002). The secrets of kalis Ilustrisimo. Boston: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0804831451. OCLC 48449942.

- Fresnoza, Florencio P (1950). Essentials of the Philippine Educational System. Manila: Abiva Publishing House. OCLC 80529874.

- Galinato, Marita Ignacio; Moody, Keith & Piggin, Colin M (1999). Upland Rice Weeds of South and Southeast Asia (Online book). Manila: International Rice Research Institute. pp. 66–67 – Chrysopogon aciculatus. ISBN 978-9712201301.

- Hillmer, Gero & Scholz, Joachim (1986). "Dependence of Quaternary Reef Terrace formation on tectonic and eustatic effects". The Philippine Scientist. 23: 58–64.

- Isidro y Santos, Antonio (1949). The Philippines Educational System. Manila: Bookman. OCLC 554406.

- NAMRIA (March 1995). NTMS (National Topographic Map Series) (Digitised map) (Map) (1 ed.). 1:50,000. Cartography by SPOT satellite imagery 1990 (Panchromatic) & 1987 (Multispectral) by SSC Satellitbild / S‑117 topographic maps by NAMRIA based on aerial photography. Fort Bonifacio, Manila: National Planning and Resource Information Authority. § 3723‑I Madridejos and 3723‑III Bantayan. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- People's Daily (25 December 1999). "More Than 600 Rescued From Sinking Ferry in Philippines" (Online archive). Archived from the original on 30 September 2011.

- "95% of Philippine reefs ruined – Reef Check". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Manila. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original (News online) on 4 December 2007.

- Philippine Daily Inquirer, Doris C Bongcac (21 August 2010). "Twister victims fall ill". Archived from the original (News online) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Robson, Craig (2011). A Field Guide to the Birds of Southeast Asia. New Holland Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1780090498.

- San Francisco Chronicle, Glen Martin (30 May 2002). "The depths of destruction / Dynamite fishing ravages Philippines' precious coral reefs" (News online). Archived from the original on 6 November 2014.

- Society of Philippine Health History (2004). "1900s : The Epidemic years". Archived from the original on 20 April 2005.

- The Freeman, Ria Mae Y. Booc (21 August 2010). "Historical Structures: Gabaldon school buildings to be preserved". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- The Freeman, Jessica J. Agua (25 July 2014). "DENR starts Bantayan Island survey to come up with management plan". Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- The Freeman, Jessica J. Agua (14 September 2014). "DENR forms TWG to review town's management plan for protected area". Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- The Freeman, Gregg M. Rubio (10 October 2014). "RDC-7: Reclassify Bantayan Island". Archived from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- The Freeman, Gregg M. Rubio (1 November 2014). "Solon pushes for "tertiary hospital" in Bantayan". p. 7. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- The Freeman, Gregg M. Rubio (4 February 2015). "First Tañon Strait summit set". Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- The Manila Bulletin, Ellalyn de Vera (11 December 2009). "Environmental group moves to protect Cebu's coral reefs". Archived from the original (News online) on 14 December 2009.

- Unisys Western Pacific Hurricane Tracking Data by Year (Tabular text data), Unisys Weather Information Systems, 18–28 November 1968

- Unisys Western Pacific Hurricane Tracking Data by Year (Tabular text data), Unisys Weather Information Systems, 3–11 November 2013

- Wiley, Mark V. (1997). Filipino Martial Culture: A Sourcebook (book). Boston: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0804820882.

- Zaide, Gregorio F (1937). Catholicism in the Philippines. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press.

- Zaide, Gregorio F (1937). Early Philippine History and Culture. Manila: Oriental Printing.

- Zaide, Gregorio F (1968). The United Nations and our Republic (revised ed.). Quezon City: Bede's Publishing House.