Barre Turnpike

The Barre Turnpike was one of over 60 toll roads in operation throughout Massachusetts in the first half of the 19th century. As described in the Act of Incorporation, February 5, 1822, the road ran

from the Common, near the meeting house in Barre; thence easterly, in the best course to Hubbardston line thence through the southerly part of Hubbardston, in the best direction to Princeton line; thence, in the best course, through part of Princeton, and through the land of David Rice; and thence through land of Jason Woodward, to a road crossing a town road, and to a road leading to Edward Goodenow's.[1]

“Edward Goodenow’s” was an inn located on Goodnow Road in Princeton, Massachusetts approximately 1.5 miles (2.6 km) northwest of the center of Princeton. It is the present-day location of the Wachusett Meadow Wildlife Sanctuary of the Mass Audubon.

The turnpike era in Massachusetts began in 1796 with the incorporation of the First Massachusetts Turnpike, which ran from Warren through Palmer to Wilbraham. However, by 1807 the turnpike movement in New England was passing its peak. After 1808 the number of charters granted and the mileage under construction declined.[2]

Petition to the legislature

In spite of the fact that by the 1820s the turnpike era was nearing its end, the sponsors of a turnpike between Barre and Princeton felt justified in appealing to the Massachusetts State Legislature for an act of incorporation.

In a letter in late January, 1821, to the Massachusetts Senate and the House of Representatives presented their justification:

The subscribers beg leave to represent that the road from Sunderland on Connecticut river to Boston is very circuitory, and that the road from Barre to Boston is likewise very circuitory and hilly and a route nearly in a direct line from said Sunderland to Boston through Barre, Hubbardston and Princeton has long been contemplated by opening a new road from the meeting house on common in Barre to Princeton a distance about eleven miles, which would lessen the distance from Sunderland to Boston about fifteen miles and from Barre to Boston about seven miles and through a country of fewer hills and of much less altitude.[3]

They indicated that a county road had previously been proposed, but was rejected by the Worcester County Court of Sessions due to the “great expense” to the towns through which it would pass. Prior to the advent of the turnpike era, roads had been maintained through a system of labor conscription. Each rate payer owed the town a certain amount of time, generally two days each year, during which they could be called upon for road maintenance. This proved to be an unsatisfactory system.[4] For a period of twenty years following the Revolutionary War, a tax-supported plan was authorized the Legislature. This required ”that each town…shall vote and raise such sum of money, to be expended in labour and materials on the highways and townways…”[5] Following as it did a war based partly on issues of unfair taxation, this system also proved unpopular. Thus the idea of “user-supported” highways was an attractive alternative.

To generate income for the maintenance of the Barre Turnpike, petitioners requested the “liberty to erect one gate on said road when made for the purpose of taking toll with such other privileges as are usually granted to Turnpike Corporations."[3] The “privileges” referred to were laid out in an “Act Defining the Powers and Duties of Turnpike Corporations”[6] The letter was signed by Seth Lee of Barre and “62 others”.

The formal request for incorporation was presented to the Senate Committee on Turnpikes on January 27, 1821 and read by the House of Representatives two days later. In accordance with the Turnpike Act of 1805, the petition was published in two Worcester newspapers, the Massachusetts Spy, and the National Aegis.

The act of incorporation

In June 1821, the Legislature took one of the initial steps towards the passage of an act of incorporation. A committee composed of Thomas Blood, Stephen Gardener and Salem Town was authorized to view the proposed route. In the fall of 1821 the committee notified the selectmen of Barre, Hubbardston and Princeton of a meeting at the house of Seth Lee in Barre to present the proposed route to the representatives of the three towns. When the Hubbardston selectmen considered how to respond the invitation, a vote was taken to “dismiss this Article".[7]

The response of the other two towns is unclear, writing in October, 1821 to the Legislature, the committee summarizes findings on the proposed route:

…that the proposed route by actual survey would shorten the distance from Barre to Boston about six miles, that the number of altitude of the hills would be much less on this route then over any other travelled way – and that the burdens imposed on the travelers for tolls would be but trifling compared with its advantages.[8]

The committee went on to point out that an earlier effort to build such a road was attempted but was rejected by the county, “not because it was not of publick utility; but that it would impose too great a burden on the town of Hubbardston”. The reference was most probably Hubbardston rejection of a proposal in 1804 to build a turnpike through the town.[9]

The way was now clear for the final petition to be presented to the legislature in January 1822. On the 5th of February, 1822, “An Act to establish the Barre Turnpike Corporation” was passed by both houses of the Massachusetts legislature

Layout committee and turnpike construction

In March 1822 the Corporation petitioned the Court of Sessions in Worcester to appoint a committee to layout the course of the turnpike. They put forward eight men of Worcester County. In September 1822 the Clerk of the Court, Abijah Bigelow, authorized the committee to layout the road. They were also to estimate any damages for the taking of land where a voluntary agreement could not be reached. They were also required to notify all interested parties and report back to the Court when their work was completed. Notices of a meeting in November at the house of Archibald Black of Barre were published in the Massachusetts Spy and the National Aegis and sent to the boards of selectmen of the three towns.

Report of the route

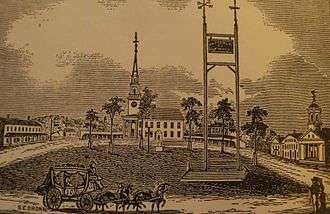

In March, 1823 the Layout Committee submitted its report to the Court of Sessions. The first part was a metes and bounds survey detailing the exact course the road was to take. It began at the former meeting house on the town common in Barre and was concurrent with the present day Massachusetts Route 62 running through the south part of Hubbardston, where a portion is still named Old Boston Turnpike. As it approached the border with Princeton, the course leaves Rt. 62 continuing on Ed Clark Road and crosses the town border on Old Colony Road. Where Old Colony Road turns sharply to the left, the Turnpike road continued into what is now part of the Ware River watershed. The Turnpike road

crossed the Ware River and continued in a straight line approximately 0.7 miles (1.1 km) crossing Gates Road and joining Goodnow Road. The Turnpike continued another mile where it reached its eastern terminus at the Goodnow Inn. The Committee also directed the owners of land over which the road was to pass to remove “all trees, wood and timber thereon…”[10] by the following 20 June 1823.

At about the same time, the Committee published a “Notice to Turnpike Makers” in the two Worcester newspapers.

The Subscribers, Directors…give notice that they will meet at Capt. Goodenow’s, in Princeton, on Wednesday, the 25th of June next…for the purpose of receiving Proposals for making about nine miles of TURNPIKE from Barre to Princeton. It is desirable that the Route be viewed previous to the Meeting. Advances in Cash will be made if requested.[11]

Estimate of compensation

Since the turnpike corporations were in part taking over the road building function of local governments, they were granted certain governmental powers. One of these was the right of eminent domain.[12] The Barre Turnpike Corporation was no exception. The Layout Committee drew up a list of 44 individuals in the three towns who were to receive compensation ranging from zero dollars to $203 (a relative value of approx. $5,000 in current dollars[13] ).[14] The total damage payments amounted to $840 (c. $21,000). The highest payment of $203 was awarded in March 1823 to David Rice of Princeton whose property bordered Gates and Old Colony Roads. The length of the Turnpike over Rice’s property was approximately 2.375 miles (3.8 km). Rice did not receive payment from the Corporation, so he requested a jury trial which found in his favor a year later, however, in March 1825 the verdict was thrown out by the court. In July of that year, David Rice died and a court dismissed the settlement. His son, Nathan, returned to court and was eventually able to receive payment of the damages.

Toll gates

The 1805 act defining the rights of turnpikes allowed for one toll gate approximately every ten miles (16.0 km). Since the entire Barre Turnpike was barely over 11 (17.7 km) miles, that permitted them one gate. In 1824 the Legislature gave the Turnpike permission to erect a gate near the house of John Davis of Princeton. This location was just west of the East Branch Ware River which made it more difficult for Turnpike users to travel around the gate to avoid tolls, a common problem with 19th century turnpikes.

Apparently the Ware River was not an adequate barrier for bypassing the Princeton toll gate. In 1825 the Corporation again returned to the Legislature with a request for a “half gate”, where one half the normal tolls could be charged. In its petition, the Corporation indicated that it had spent $10,000 (c. $250,000 relative value in current dollars) to build a new road in part because “the expense [of building its own road] would be insupportable by Hubbardston”.[15] The corporation claimed that “the traveler avoids the [Princeton] gate and passes by the town of Hubbardston.”

In May 1825 Hubbardston officials wrote to the Legislature objecting to the erection of a new half gate. They protested that it “would be very troublesome and expensive…[to] persons travelling from the Northeasterly part of the County or State to the Westerly part thereof”.[16] They stated the Corporation received permission to build the road with the understanding that no expense would be incurred by the inhabitants of Hubbardston when traveling to Barre. They added that if travelers left the road in the spring, it was because it was “mud and miry” and not to avoid a gate.

In spite of Hubbardston’s remonstrances, construction the half gate was approved on February 15, 1826 somewhere between the westerly side of the Burnshirt River bridge and the present day Everett Road in Barre.

Signs of financial problems

The erection of a second, half gate was just one of several indications that the Barre Turnpike Corporation, barely three years after its incorporation, was having financial difficulties. Writing in 1830, two Massachusetts authors concluded:

The turnpikes…have frequently proved a convenience to the public; but to their projectors they have generally been unproductive and very frequently ruinous; the tolls gather from the travelers being too inconsiderable to keep the roads in repair and refund to the owners their original cost.[17]

A notice appeared in the September 19, 1827 edition of the Massachusetts Spy announcing a sale of delinquent shares at the Davis Inn in Princeton. Elsewhere in the same edition of the paper was a notice of a proposal to the Commissioners of Highways for several new, publicly funded county “Common Roads” – another sign that the era of privately financed highways was nearing its end. It is unclear just why the proprietors of the Barre Turnpike originally decided so late in the turnpike era to incorporate and construct the new toll road. The Turnpike had barely opened to traffic, yet in 1825, with few exceptions, turnpike stocks were then notoriously worthless.[18]

The end of the turnpike

The final chapter began with a meeting at Abijah Clark’s house in Hubbardston on September 3, 1831. The Turnpike proprietors gave notice to the Worcester County Commissioners that they had voted “to relinquish and abandon their franchise as to the whole of the said turnpike road”.[19] On the same page of the Spy another notice was published which provided another piece of evidence that the Turnpike Era was ending. The Boston and Lowell Rail Road announced that they were “prepared to contract for making of various sections of the Road. They will also contract for the building of Bridges and Culverts…”

On December 27, 1831 the Commissioners accepted the Barre Turnpike Corporation’s petition. In the following year they met “to lay out, locate, and establish a public highway or common road over the turnpike road aforesaid”.[20]

Following this approval to convert the former toll road into public highway, a town meeting in Princeton in August, 1832 voted to approve an article to fund their portion of the road:

To see what sum of money the Town will raise to make a County road recently located in said Princeton over the Barre Turnpike (so called) and also to choose a Committee to expend said money in making said road, or act any thing related thereto.[21]

References

- ↑ Chap. 45, Sect. 1, 1821, An Act to establish the Barre Turnpike Corporation, Private and Special Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

- ↑ Parks, Roger N., “Roads in New England, 1790–1840”, Old Sturbridge Village Research Paper, (1965)

- 1 2 Legislative packet, Barre Turnpike Corporation, January 27, 1821, Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Taylor, Philip E. The Turnpike Era in New England, Mss. Thesis in Yale University . (1934), p. 70

- ↑ Acts and Resolves of Massachusetts, 1786-87, Chapter 81.

- ↑ Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,( March 16, 1805)

- ↑ Minutes for the Hubbardston Board of Selectmen,( October 11, 1821), Town Clerk, Hubbardston, Massachusetts

- ↑ Letter to the Massachusetts Legislature, (October 17, 1821), Legislative packet, Barre Turnpike Corporation, Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Rev. J. M. Stowe, “History of the Town of Hubbardston”, (1881)

- ↑ Legislative packet, Barre Turnpike Corporation, March 25, 1823, Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Massachusetts Spy, (June 11, 1823)

- ↑ , Frederic J. Wood The Turnpikes of New England , Marshall Jones Co., Boston (1919). p. 32

- ↑ Measuring Worth

- ↑ Report to the Worcester Court of Sessions, (November 15, 1822), Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Petition to the Massachusetts Legislature, legislative packet for “An Act in addition to an Act establishing the Barre Turnpike Corporation, Chapter 70, (1825) , Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Letter to the Massachusetts Legislature from Hubbardston, (May, 1825), Legislative packet, Barre Turnpike Corporation, Massachusetts Archives

- ↑ Gordon Carter, William Hathorne Brooks, A Geography of Massachusetts, (Boston, 1830)

- ↑ J. E. A. Smith, The History of Pittsfield, (Springfield, 1876)

- ↑ Massachusetts Spy, Nov. 16, 1831

- ↑ Massachusetts Spy, April 11, 1832

- ↑ Princeton Town Meeting Minutes, August 27, 1832

External links

- Barre Massachusetts Historical Society

- Princeton Massachusetts Historical Society

- Harvard Forest 1830 Map of Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Archives

- Google Map of Barre Turnpike