Barzillai J. Chambers

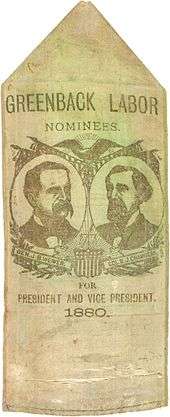

Barzillai Jefferson Chambers (December 5, 1817 – September 16, 1895) was an American surveyor, lawyer, and politician of the Gilded Age. Born in Kentucky, he moved to Texas to join that state's war for independence against Mexico. Chambers stayed in Texas after its independence and annexation by the United States, earning a living as a surveyor and farmer in Johnson County. In the American Civil War, he served briefly in the Confederate army, then returned to his farming and business interests, becoming part-owner of a bank in his hometown of Cleburne. In the 1870s, Chambers became concerned with farming and monetary issues in politics, eventually joining the nascent Greenback Party in 1877. He ran unsuccessfully for Vice President on the Greenback ticket with presidential nominee James B. Weaver of Iowa in 1880. The Greenback nominees finished in a distant third place, receiving only 3.3% of the popular vote and no electoral votes. After the election, Chambers remained active in Greenback politics in Texas until the party's demise in the late 1880s. He died at his home in Cleburne in 1895.

Early life

Barzillai Jefferson Chambers[lower-alpha 1] was born in 1817 in Montgomery County, Kentucky, the son of Walker Chambers and Talitha Cumi Mothershead Chambers.[2] Chambers lived on his father's Kentucky farm for the first twenty years of his life.[4] In 1837, he followed his uncle, Thomas Jefferson Chambers, to Texas. The elder Chambers, who had lived in Texas since 1830, had raised a regiment to join the Texas Revolution and commissioned his nephew as a captain and his aide-de-camp.[2] After helping his uncle to recruit soldiers in Kentucky, the two departed for Texas but arrived too late to see action.[2] Chambers was discharged from the Texas army in 1838 and remained in the state, becoming a surveyor in the southern part of the state.[5] The next year, he was appointed deputy surveyor for north central Texas, between the Brazos and Trinity rivers.[2] The area had little white settlement at the time, and Chambers "narrowly escaped Indian attacks on several occasions."[2]

Chambers continued to work as a surveyor in the 1840s while also engaging in land speculation. By 1850, he was promoted to district surveyor; he had, by then, acquired 10,000 acres of land in Navarro and Johnson counties.[2] He devoted some of the land to farming, but also donated some lots to Johnson County for the erection of the county seat, in Cleburne.[6] He became a lawyer in 1860, but never developed a sizable law practice.[2] Chambers married three times: first in 1852 to Susan Wood, who died the next year; secondly in 1854 to Emma Montgomery, who died in childbirth the next year; and finally in 1861 to Harriet Killough.[7] Chambers had no children who survived infancy with the first two wives, but with his third wife he would have three children: Mary, Patrick, and Isabella.[7]

Business and political career

After the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States in 1860, Chambers, a Democrat, served on two committees in Navarro County that drafted resolutions opposed to Lincoln and racial equality.[8] He supported Texas's secession from the Union in 1861 and adhesion to the newly formed Confederacy, but, being 44 years old at the subsequent outbreak of the Civil War, did not immediately enlist.[8] Although he was exempted from the Confederacy's military draft, Chambers thought the exemption unjust, and wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis to protest it.[9] In 1864, he did enlist for six months in the 1st Regiment of Texas State Troops, but saw no action.[8] After the war, Chambers returned to farming but also became a half-owner of Cleburne's only bank from 1871 to 1875.[8] By that time, Chambers was the largest landowner in Johnson County.[7] He also actively promoted the Dallas and Cleburne Railroad, working unsuccessfully to get the railroad to make its stock available to all local citizens.[8]

Chambers's political opinions after the war were at first concerned with government debt. In an 1868 article in the Cleburne Chronicle, Chambers argued against all interest-bearing national debts, and for a general policy of inflationism.[10] Running as a Democrat, he was elected an alderman of Cleburne and was a delegate to Texas's constitutional convention of 1875.[10] The proposed constitution that emerged was primarily an attempt to reverse the changes made by Republicans during Reconstruction. Chambers opposed its adoption, not for that reason, but because "while taxation was unequally thrown upon property alone, unqualified suffrage was given to every man".[10] He also opposed the homestead exemption, "which protect[s] the debtor class from the just demands of the creditor class."[10] Nevertheless, the constitution was adopted by a two-to-one majority.[11]

Greenback party

When the Democratic Party's platform did not endorse his inflationist views in 1876, Chambers quit the party.[11] The new Greenback Party (sometimes called the Greenback-Labor Party,) had not yet begun to organize in Texas, but its positions better suited Chambers and he joined in 1877.[11] The Greenbackers, in the words of one author, "anticipated by almost fifty years the progressive legislation of the first quarter of the twentieth century."[12] Their platform advocated an eight-hour work day, safety regulations in factories, and prohibition of child labor.[12] Their most prominent position, however, and the one from which their name was derived, was support for the continued issuance of the greenback dollar.[12]

During the Civil War, Congress had authorized "greenbacks," a new form of fiat money that was redeemable not in gold but in government bonds.[13] The greenbacks had helped to finance the war when the government's gold supply did not keep pace with the expanding costs of maintaining the armies. When the crisis had passed, many in both parties, especially in the East, wanted to return the nation's currency to a gold standard as soon as possible.[14] The Specie Payment Resumption Act, passed in 1875, ordered that greenbacks be gradually withdrawn and replaced with gold-backed currency beginning in 1879. At the same time, economic depression had made it more expensive for debtors to pay debts they had contracted when currency was less valuable.[15] Farmers and laborers, especially, clamored for the return of coinage in both gold and silver, believing the increased money supply would restore wages and property values.[16] With neither major party willing to endorse inflation, some partisans of loose money joined the new Greenback faction.[17]

Chambers rose quickly in the new party's leadership, serving as a delegate to their state convention in July 1878.[11] Initially a candidate for state land commissioner, Chambers withdrew his name in August of that year to allow former Republican Jacob Kuechler to win a unanimous nomination; he was nominated instead for a seat in the state legislature.[11] Ten Greenbackers were elected to the legislature that year, but Chambers was not among them.[18] During the campaign, Chambers published a pamphlet attacking the Democratic candidates and calling for Congress to create "a sufficient amount of paper money, making it equal to gold and silver, and full legal tender for all debts".[11] While it did not help his own election, the pamphlet was widely circulated within the party and raised Chambers's profile among Greenbackers.[19]

1880 election

By 1879, the Greenback coalition had splintered, and Chambers became affiliated with the faction most prominent in the South and West, called the "Union Greenback Labor Party," led by Marcus M. "Brick" Pomeroy. Pomeroy's faction was more radical and emphasized its independence, suggesting that Eastern Greenbackers were likely to "sell out the party at any time to the Democrats."[20] Chambers was chosen as a delegate to the Pomeroy faction's 1880 national convention in St. Louis.[21] The 212 delegates nominated Stephen D. Dillaye of New York for President and Chambers for Vice President.[21] Accepting the nomination, Chambers called for unity between the Greenback factions and restated his belief in the party's goals, and attacked bankers as "Huns and Vandals."[22] To further promote his views, he purchased a small newspaper, the Cleburne Avalanche, and spoke at the state convention in Texas in May 1880.[22]

The more Eastern-oriented faction of the Greenbacks, called the "National Greenback Party," held its convention in Chicago that June, and Chambers attended along with others from the Pomeroy faction, hoping to heal the party split. The two factions resolved their differences and wrote a joint platform.[22] The Greenbackers also agreed to admit forty-four delegates of the Socialist Labor Party.[23] Dillaye stepped aside to allow the nomination of James B. Weaver of Iowa, a Civil War general and Congressman. Chambers was proposed for Vice President by the reunited party, as was Absolom M. West of Mississippi; Chambers was victorious on the first ballot, by 403 votes to 311. West moved that the nomination be made unanimous, which it was.[22]

Chambers gave speeches on his way back to Texas, castigating the banks and defending the admission of socialists to the convention as "simply a body of men enlisted in the cause of human rights."[22] In his official acceptance letter, he called for expansion of the currency, immigration restriction to help workingmen compete "with Chinese serf labor," and the forfeiture of all unfulfilled railroad grants.[24] On July 8, before reaching home, Chambers fell as he exited his train in Kosse, Texas, and broke two ribs.[24] He was confined to bed for several weeks and considered withdrawing from the race, but decided against it. His efforts, however, were limited by his injuries, and his only contribution to the campaign was to publish his newspaper, renamed the Cleburne Greenbacker.[24] Greenbackers had high hopes for the 1880 election, but were disappointed with the result: Weaver and Chambers won just over 300,000 votes (3.3% of the popular vote) and did not carry a single state in the electoral college.[24]

Post-election life

Chambers remained active in politics after the 1880 election. He served as chairman of the Texas Greenback Party in 1882 as George Washington Jones received the party's endorsement for governor. He was unsuccessful, and Chambers worried that the party was becoming "disorganized and disintegrated beyond the hope of a successful rally."[24] In 1884, Jones ran again for governor and Chambers broke with him on the question of whether the state should lease public lands or let cattlemen use them without payment (Chambers favored the former option).[25] He also criticized the party's presidential nominee that year, Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts, for attacking monopolies without offering any suggestions on how to reform them.[25] After the 1884 election, Chambers had little involvement in politics. The Greenback Party fell apart by 1888, but many of its ideas and members found a home in the People's Party, which arose in the early 1890s.[26] Chambers made his last foray into politics in 1890 in two letters to the Southern Mercury, a newspaper of the Farmers' Alliance, in which he again condemned monopolies and corporations, and suggested that all laws creating them be repealed.[25] He was encouraged by the growth of the People's Party, but old age and ill health kept him from being an active member. Chambers died at his home on September 16, 1895, and was buried in Cleburne Memorial Cemetery.[26]

Notes

- ↑ Many early sources list Chambers's first name as "Benjamin".[1] Most recent scholarship gives his name as "Barzillai." Alwyn Barr's 1967 article refers to him as "Barzillai."[2] Darcy G. Richardson, writing in 2004, says that in Chambers's lifetime he was "often mistakenly referred to as 'Benjamin' Chambers".[3]

References

- ↑ Byrd, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barr, p. 276.

- ↑ Richardson, p. 513.

- ↑ Memorial Biography, p. 86.

- ↑ Memorial Biography, p. 87.

- ↑ Byrd, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Memorial Biography, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barr, p. 277.

- ↑ Kennedy et al., p. 146.

- 1 2 3 4 Barr, p. 278.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Barr, p. 279.

- 1 2 3 Clancy, pp. 163-164.

- ↑ Unger, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Unger, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Unger, pp. 228–233.

- ↑ Martin, p. 163.

- ↑ Doolen, p. 436.

- ↑ Martin, p. 169.

- ↑ Kennedy et al., p. 147.

- ↑ Barr, p. 280; Doolen, pp. 439–440.

- 1 2 Barr, p. 280.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barr, p. 281.

- ↑ Doolen, p. 447.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Barr, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 Barr, p. 283.

- 1 2 Barr, p. 284.

Sources

- Books

- A Memorial and Biographical History of Johnson and Hill Counties, Texas. Chicago, Illinois: Lewis Publishing Company. 1892. OCLC 7319318.

- Byrd, A. J. (1879). History and Description of Johnson County and Its Principal Towns. Marshall, Texas: Jennings Bros. OCLC 210669208.

- Clancy, Herbert J. (1958). The Presidential Election of 1880. Chicago, Illinois: Loyola University Press. ISBN 978-1-258-19190-0.

- Kennedy, E.B.; Dillaye, S.D.; Hill, Henry (1880). Our Presidential Candidates and Political Compendium. Newark, New Jersey: F.C. Bliss & Co. OCLC 9056547.

- Richardson, Darcy G. (2004). Others: Third Party Politics from the Nation's Founding to the Rise and Fall of the Greenback-Labor Party. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 0-595-31723-5.

- Unger, Irwin (1964). The Greenback Era: A Social and Political History of American Finance, 1865–1879. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-59740-168-4.

- Articles

- Barr, Alwyn (October 1967). "B. J. Chambers and the Greenback Party Split". Mid-America. 49: 276–284.

- Doolen, Richard M. (Winter 1972). ""Brick" Pomeroy and the Greenback Clubs". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 65 (4): 434–450. JSTOR 40191206.

- Martin, Roscoe C. (January 1927). "The Greenback Party in Texas". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 30 (3): 161–177. JSTOR 30237195.