Battle of Pichincha

| Battle of Pichincha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Ecuadorian War of Independence | |||||||

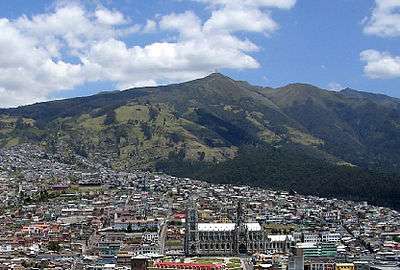

Quito and the Pichincha volcano | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Antonio José de Sucre |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,971 men | 1,894 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

200 killed 140 wounded |

400 killed 190 wounded 1,260 prisoners | ||||||

The Battle of Pichincha took place on 24 May 1822, on the slopes of the Pichincha volcano, 3,500 meters above sea-level, right next to the city of Quito, in modern Ecuador.

The encounter, fought in the context of the Spanish American wars of independence, pitted a Patriot army under General Antonio José de Sucre against a Royalist army commanded by Field Marshal Melchor Aymerich. The defeat of the Royalist forces loyal to Spain brought about the liberation of Quito, and secured the independence of the provinces belonging to the Real Audiencia de Quito, or Presidencia de Quito, the Spanish colonial administrative jurisdiction from which the Republic of Ecuador would eventually emerge.

Background

The military campaign for the independence of the Presidencia de Quito could be said to have begun on October 9, 1820, when the port-city of Guayaquil proclaimed its independence from Spanish rule after a quick and almost bloodless revolt against the local colonial garrison. The leaders of the movement, a combination of Venezuelan and Peruvian pro-independence officers from the colonial army, along with local intellectuals and patriots, set up a governing council and raised a military force with the purpose of defending the city and carrying the independence movement to the other provinces in the country.

By that time, the tide of the wars of independence in South America had turned decisively against Spain: Simón Bolívar's victory at the Battle of Boyacá (August 7, 1819) had sealed the independence of the former Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada, while to the south, José de San Martín, having landed with his army on the Peruvian coast in September 1820, was preparing the campaign for the independence of the Viceroyalty of Perú.

First Campaigns in the Real Audiencia de Quito (1820-1821)

There were three military attempts to liberate the territory of the Real Audiencia.

The first campaign was carried out by the new independent government of Guayaquil, which raised an army with local recruits — perhaps 1,800 men strong — and in November 1820 sent it towards the central highlands, with the purpose of encouraging other cities to join the independentist cause. After some initial successes, which included the declaration of independence of Cuenca, on November 3, 1820, the Patriots suffered a costly defeat at the hands of the Royalist army at the Battle of Huachi (November 22, 1820), near Ambato, forcing the Patriots to retreat back to the coastal lowlands.

By February 1821, Guayaquil began to receive reinforcements, weapons and supplies, sent by Simón Bolívar, President of the fledgling Republic of Colombia. In May of that year, Brigadier General Antonio José de Sucre, Commander in Chief of the Southern Division of the Colombian Army and Bolívar's most trusted military subordinate, came to Guayaquil. He was to take overall command of the new Patriot army, and begin operations aimed at the liberation of Quito and the entire territory of the Real Audiencia de Quito. Bolívar's ultimate political goal was the incorporation of all the provinces of the Real Audiencia into Colombia, including Guayaquil, still undecided whether to join Perú or Colombia, and with a strong current of opinion in favour of setting up its own republic. Time was of the essence, as it was vital to force the issue before General José de San Martín, still fighting in Perú, could come up to bring forward any Peruvian claims to the important port-city.

Sucre's advance up the Andes began in July, 1821. As had happened in the first campaign, after some initial successes, Sucre was defeated by the Royalist army on September 12, 1821, coincidentally at the same place as the previous battle (resulting in a Second Battle of Huachi). This second campaign came to an end with the signing of an armistice between the Patriots and the Spanish on November 19, 1821.

The Final Campaign of Quito (1822)

Planning

Back in Guayaquil, General Sucre concluded that the best course of action for the next campaign would be to drop any further attempt of a direct advance to Quito by way of Guaranda, in favor of an indirect approach, marching first to the southern highlands and Cuenca before wheeling north and advancing up the inter-Andean "corridor" towards Quito. This plan had several advantages. Retaking Cuenca would cut all communications between Quito and Lima, and would allow Sucre to wait for the reinforcements that in the meantime San Martín had promised would come from Perú. Also, a more progressive and slower advance from the lowlands up the Andes into the southern highlands would allow for a gradual adaptation of the troops to the physiological effects of the altitude. Moreover, it was the only way to avoid another direct clash in unfavorable conditions with the Royalist forces coming down from Quito.

Renewed campaign, 1822

At the beginning of January 1822, Sucre opened the new campaign. His army consisted now of approximately 1,700 men, including veterans from the previous campaigns as well as raw recruits. There were men from the lowlands of the Province of Guayaquil and volunteers who had come down from the highlands, both contingents soon to be organized into the Yaguachi Battalion; there were Colombians sent by Bolívar, a number of Spanish-born officers and men who had changed sides; a full battalion of British volunteers (the Albión); and even small numbers of Frenchmen. On January 18, 1822, the Patriot army marched on Machala, in the southern lowlands. On February 9, 1822, having crossed the Andes, Sucre entered the town of Saraguro, where he was joined by the 1,200 men of the Peruvian Division, the contingent previously promised by San Martín. This force was mostly Peruvian recruits, with Argentinian and Chilean officers. Facing a multinational force numbering around 3,000 men, the 900-strong Royalist cavalry detachment covering Cuenca withdrew to the north, being pursued at a distance by Patriot cavalry. Cuenca was thus retaken by Sucre on February 21, 1822, without a shot being fired.

During March and April, the Royalists continued to march northwards, successfully avoiding battle with the Patriot cavalry. Nevertheless, on April 21, 1822, a ferocious cavalry encounter did take place at Tapi, near Riobamba. At the end of the day, the Royalists abandoned the field, while the main body of Sucre's army proceeded to take Riobamba, staying there until April 28, before renewing the advance to the north.

Final approach to Quito

By May 2, 1822, Sucre's main force had reached the city of Latacunga, 90 km south of Quito. There he proceeded to refit his troops and fill up the ranks with new volunteers from the nearby towns, waiting for the arrival of reinforcements, mainly the Colombian Alto Magdalena Battalion, and new intelligence on the whereabouts of the Royalist army. Aymerich had meanwhile set up strongpoints and artillery positions on the main mountain passes leading to the Quito basin. Sucre, bent on avoiding a frontal clash on unfavorable terrain, decided to advance along the flanks of the Royalist positions, marching along the slopes of the Cotopaxi volcano in order to reach the Chillos valley, at the rear of the Royalist blocking positions. By May 14, the Royalist Army, sensing Sucre's intentions, began to fall back, reaching Quito on May 16. Two days later, and after a most difficult march, Sucre's main body occupied Sangolquí.

Climbing Pichincha

On the night of 23–24 May 1822, the Patriot Army, 2,971 men strong, began to climb up the slopes of Pichincha. In the vanguard were the 200 Colombians of the Alto Magdalena, followed by Sucre's main body. Bringing up the rear were the Scots and Irish of the Albión, protecting the ammunitions train. In spite of the strenuous efforts made by the troops, the advance up the slopes of the volcano was slower than anticipated, as the light rain that fell during the night turned the trails leading up the mountain into quagmires.

By dawn, to Sucre's dismay, the army had not been able to make much progress, finding itself just halfway along the mountain, 3,500 meters above sea-level, and in full view of the Royalist sentries down in Quito. At 8 o'clock, anxious about the slow progress of the Albión, and with his troops exhausted and suffering from altitude sickness, Sucre ordered a stop, ordering his commanders to hide their battalions as best they could. He sent part of the Cazadores del Paya battalion (Peruvians) forward in a reconnaissance role, to be followed by the Trujillo, another Peruvian battalion. One and a half hours later, much to their surprise, the men of the Paya were suddenly struck by a well-aimed musket volley. The battle had started.

Battle, 3,500 meters above sea-level

Unknown to Sucre, when dawn came, the sentries posted around Quito had indeed caught sight of the Patriot troops marching up the volcano. Aymerich, aware now of the young General's intention to flank him by climbing Pichincha, ordered his army—1,894 men—to ascend the mountain at once, intent on facing Sucre then and there.

Having made contact in the most unlikely of places, both commanders had no choice but to throw their troops piecemeal into the battle. There was little room to manoeuvre on the steep slopes of Pichincha, amid deep gullies and dense undergrowth. The men from the Paya, recovering from the initial shock, took positions under withering fire, waiting for the Trujillo to come up. A startled Sucre, hoping only that the Spaniards would be even more exhausted than his own troops, began by sending up the Yaguachi Battalion (Ecuadorians). The Colombians of the Alto Magdalena tried to make a flanking move, but to no avail, as the broken terrain made it impossible. Soon, the Paya, Barrezueta and Yaguachi, suffering heavy losses and lacking enough ammunition, began to fall back.

Everything now seemed to depend on the personnel of the British Legions bringing up the much needed reserve ammunition and additional personnel, but whose exact whereabouts were unknown. As time went by, the Royalists seemed to gain the upper hand. The Trujillo was forced to fall back, while the Piura Battalion (Peruvians), fled before making contact with the enemy. In desperation, the part of the Paya held in reserve was ordered to make a bayonet charge. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but the situation was somehow stabilized for the Patriots.

Nevertheless, Melchor Aymerich had an ace up his sleeve, so to speak. During the march up Pichincha, he had detached his crack Aragón battalion from his main force, ordering it to make for the top of the volcano, so as to fall upon the rear of the Patriots when the time came, and break their lines. The Aragón battalion — a veteran Spaniard unit that had seen plenty of action both during the Peninsular War and in South America — was now above the Patriots. As luck would have it, just as it was about to charge down onto the faltering Patriot line, it was stopped dead in its tracks by the English, Scots and Irish veterans of Albión, which made a surprise entry into the battle. As it was, the Albión had actually advanced to a position higher than the Spaniards. Soon, the Magdalena battalion joined in the fight, and the Aragón, after suffering heavy losses, was put out of action. The Colombians from the Magdalena then went up to the line to replace the Paya, which was forced to pull back, and charged upon the Royalist line, which was finally broken. At midday, Aymerich ordered the retreat. The Royalist army, now disorganized and exhausted, retreated down the slopes of Pichincha towards Quito. Although some units descended to Quito in disarray, harassed by the Magdalena battalion charging after them, others retreated in orderly fashion. The Colombians reached the outer limits of Quito, but did not go any further, acting on orders from their commanding officer who prudently decided against letting his soldiers enter the city. Thus, the Battle of Pichincha had ended. From the moment of first contact to the order of retreat, it had lasted no more than three hours.

Sucre's after-action report

The day after the battle, May 25, Sucre wrote down his report of the action:

- "The events at Pichincha have brought about the occupation of this city [Quito] as well as its forts on the afternoon of the 25, the possession and peace of the entire Department, and the taking of 1,100 prisoners, 160 officers, 14 artillery pieces, 1,700 rifles...Four hundred enemy soldiers and two hundred of our own lie dead on the field of battle; we have also counted 190 Spanish wounded, and 140 of our own...[A]mong the latter are Captains Cabal, Castro, and Alzuro; Lieutenants Calderón and Ramírez, and Second Lieutenants Borrero and Arango...I make a special mention of Lieutenant Calderón's conduct, who having suffered four wounds in succession, refused to leave the field. He will probably die, but I am sure the Government of the Republic will compensate his family for the services rendered by this heroic officer."

Thus was born the legend of native Cuencan Abdón Calderón Garaycoa, who along with Sucre came to symbolize the memory of Pichincha for the new Ecuadorian nation.

Aftermath

While in the general context of the Wars of Independence, the Battle of Pichincha stands as a minor clash, both in terms of its duration and the number of troops involved, its results were to be anything but insignificant. On May 25, 1822, Sucre and his army entered the city of Quito, where he accepted the surrender of all the Spanish forces then based in what the Colombian government called the "Department of Quito", considered by that Government as an integral part of the Republic of Colombia since its creation on December 17, 1819.

Previously, when Sucre had recaptured Cuenca, on February 21, 1822, he had obtained from its local Council a decree by which it proclaimed the integration of the city and its province into the Republic of Colombia.

Now, the surrender of Quito, which put an end to the Royalist resistance in the northern province of Pasto, allowed Bolívar to finally come down to Quito, which he entered on June 16, 1822. Amid the general enthusiasm of the population, the former Province of Quito was officially incorporated into the Republic of Colombia.

One more piece to the puzzle remained, Guayaquil, still undecided about its future. The presence of Bolívar and the victorious Colombian army in the city finally forced the hands of the Guayaquilenos, whose governing council proclaimed the Province of Guayaquil as part of Colombia on July 13, 1822.

Eight years later, in 1830, the three southern Departments of Colombia, Quito (now renamed Ecuador), Guayaquil and Cuenca, would secede from that country to constitute a new nation, which took the name of Republic of Ecuador.

Order of battle

PATRIOT ARMY

- Supreme Commander:

- Brigadier General Antonio José de Sucre, Colombian Army

- Commander in Chief, 'División Unidad al Sur de la República'

- División de Colombia (Colombian Division): General José Mires

- Albión Battalion (Scottish, Irish, English): Lt Col Mackintosh

- Paya Rifle-Hunters Battalion (Peruvians): Lt Col Leal

- Alto Magdalena Battalion (Colombians): Col Córdova

- Yaguachi Battalion (Ecuadorians): Col Ortega

- Southern Dragoons (Peruvians, Argentinians): Lt Col Rasch

- División del Perú (Peruvian Division): Colonel Andrés de Santa Cruz

- Trujillo Battalion (Peruvians): Col Olazábal

- Piura Battalion (Peruvians): Col Villa

- Horse Grenadiers of the Andes, 1st Squadron (Argentinians, Chileans): Col Lavalle

- Mounted Rifle Hunters, 1st Squadron (Argentinians, Chileans): Lt Col Arenales

- Artillery Battery: Capt Klinger

ROYALIST ARMY

- Supreme Commander:

- Field-Marshal Melchor Aymerich, Spanish Army

- Capitán General, Kingdom of Santa Fé

- 1st Aragón Battalion (Spanish): Col Valdez

- Cádiz Sharpshooters Battalion: Col de Albal

- Cazadores Ligeros de Constitución: Col Toscano

- HM Queen Isabel's Dragoons, 1st Squadron: Col Moles

- Granada Dragoons, 1st Squadron: Col Vizcarra

- Presidential Guard Dragoons, 1st Squadron: Lt Col Mercadillo

- HM King Ferdinand VII's Own Hussars, 1st Squadron: Col Allimeda

- Artillery Battery: Col Ovalle

La Cima de la Libertad

The area where the battle took place has now a large monument and a Champ de Mars (Parade grounds) and a museum and is called colloquially "La Cima de la Libertad" (The Summit of Liberty).

References

- Salvat Editores (Eds.), Historia del Ecuador, Vol. 5. Salvat Editores, Quito, 1980. ISBN 84-345-4065-7.

- Enrique Ayala Mora (Ed.), Nueva Historia del Ecuador, Vol. 6. Corporación Editora Nacional, Quito, 1983/1989. ISBN 9978-84-008-7.

Coordinates: 0°13′8.72″S 78°31′38.15″W / 0.2190889°S 78.5272639°W