First Battle of Vác (1849)

| First Battle of Vác | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total:11,592 men 36 cannons Did not participate: Detached troops from I. corps: 2973 men 20 cannons |

8,250 men 26 cannons | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total 150 men |

Total 422 men - 60 dead - 147 wounded - 215 missing or captured 1 battery[1] | ||||||

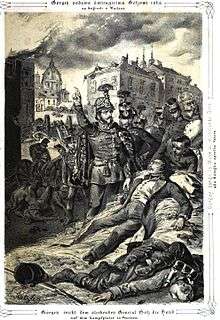

The Battle of Vác, fought on 10 April 1849, was one of the two important battles which took place in the same city in the Spring Campaign of the Hungarian War of Independence from 1848–1849, fought between the Habsburg Empire and the Hungarian Revolutionary Army. This battle was the starting point of the second phase of the Spring Campaign, which had the purpose to relieve the fortress of Komárom from the imperial siege, and with this to encircle the Habsburg imperial forces headquartered in the Hungarian capitals of Buda and Pest. The Hungarians won the battle, in which the Austrian commander Major General Christian Götz was fatally wounded, dying after the battle. His body was buried by the Hungarian high commander Artúr Görgei with military honors, this being one of the examples of gallantry and high respect for the fallen enemy hero in the Hungarian War for Independence.

Background

With the Battle of Isaszeg the Hungarian Revolutionary Army led by Artúr Görgei managed to force the Habsburg imperial army led by Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz to retreat towards the Hungarian capitals (Pest and Buda), liberating the Hungarian territories between the Tisza and the Danube rivers. The imperial troops retreated to Pest, forming a defensive line before it, which was difficult to conquer.[2] This was understood also by the Hungarian commanders, after the Hungarian army encircled Pest until the Danube, and stood in this position until 9th April, and were ready for a battle. The imperial army did not accepted to fight but retreated in the capital city.[3] In 7th April a new campaign plan was made. According to this plan the Hungarian army had to split, General Lajos Aulich with the II. Hungarian Army Corps, and the division of Colonel Lajos Asbóth remained infront of Pest, doing such military maneuvers which have to make the imperials to believe that the whole Hungarian army is there, diverting their attention from north, where the real Hungarian attack had to start with the I., III. and the VII., corps which had to go westwards, on the northern bank of the Danube via Komárom, to relieve it from the imperial siege.[4] The Kmety division of the VII. corps had to cover the three corps march, and after the I. and the III. corps occupied Vác, the division had to secure the town, while the rest of the troops together with the two remaining divisions of the VII. corps, had to advance to Garam river, than heading for the south to relieve the northern section of Austrian siege of the fortress of Komárom.[5] After this, they had to cross the Danube and relieve the southern section of the siege. In the eventuality of finishing all of these with success, the imperials had only two chances: Or to retreat from Middle Hungary towards Viena, or face the encirclement from the Hungarian troops in the Hungarian capitals.[6] This plan was very risky (as was the first plan of the Spring Campaign too) because if Windisch-Grätz would had discovered that in front of Pest remained only a Hungarian corps, with an attack could destroy Aulich's troops, and with this he could easily cut the support lines of the main Hungarian army, and even occupy Debrecen, the seat of the Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament and the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary), or he could encircle the three corps advancing to relieve Komárom.[7] Although the president of the National Defense Committee (interim government of Hungary), Lajos Kossuth, who after the battle of Isaszeg, went to Gödöllő, the Hungarian headquarters, wanted a direct attack on Pest, finally was convinced by Görgey that his and the other generals plan is better.[8] To secure the succes of the Hungarian army, the National Defense Committee sent from Debrecen 100 wagons with munitions.[9]

3.jpg)

After the Battle of Isaszeg Field Marshal Windisch-Grätz, ordered to the division, which was quartered in Balassagyarmat, to defend the Ipoly valley, led by Lieutenant General Georg von Ramberg, to move to Vác, to secure the Danube Bend from a Hungarian attack, but in the same time made the mistake to order to Lieutenant General Anton Csorich, who actually was defending with his division Vác, to move to Pest.[10] If two imperial divisions would had defending Vác when the Hungarians attacked, they would have had more chances to repel it. At 10th of April, when the attack of the Hungarian army against Vác was planned, Görgey feared an imperial attack against his troops in the region before Pest. And indeed Windisch-Grätz ordered to his I. and III. corps a general advance, in order to learn if the Hungarian main army is in front of Pest, or moved northwards. But the II. Hungarian corps led by General Aulich together with the VII. corps, and much of the I. corps, repelled the attack with easiness. [11] In the same time the misleading movements of Aulich and Asbóth's, managed to catch the eye of the imperials, who did not observed the march of the III. corps, led by János Damjanich.[12] So the field Marshal didn't obtained the informations which he needed. The inefficiency of the imperial reconnaissance is shown by the fact, that on 12th and 14th April (that means 4 days after the battle of Vác, the Hungarian main army departed towards Komárom, and only the II. corps remained there), Anton Csorich reported, that Pest is in danger to be attacked by important Hungarian forces.[13] The troops of Lajos Aulich and Lajos Asbóth made their job, of making the imperials to believe that the main Hungarian army is still in front of the capital, so well that Windisch-Grätz, until his dismissal, and the interim main commander, Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić, until the arrival of Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden, who was named as the new high commander, had no courage to do anything.[14] In contrast, the Hungarian reconnaissance worked excellent, learning that WindischGrätz still waits before Pest, with three army corps, the Hungarian attack, and at Vác the Ramberg division, composed of the Götz and Jablonowski brigades, blocks the road to the Danube valley and to the Vág river.[15]

Prelude

Because of the participation of the VII. and much of the I. corps in the skirmishes around Pest, the Hungarian army which moved towards Vác, was composed only of the III. corps and the brigade led by Lieutenant-Colonel János Bobich from the I. corps. The rest of the first corps arrived to Vác only after the end of the battle.[16] According to László Pusztaszeri (in 1984) the whole I. Hungarian corps joined the advancement of the III. corps towards Vác, but this is unlikely.[17] But the work of the military historian Róbert Hermann, written 20 years later (2004) states that only the Bobich brigade from the I. corps marched with the III. corps towards Vác.[18] So it is more likely that Hermann was right. They started to move towards north, in 9th April at 4 o'clock in the afternoon, followed by the VII. corps, which was extracted, step by step, from among the Hungarian troops, which were doing demonstration maneuvers.[19]

In the morning of the 10th of April, after his troops arrived to Vác, General Damjanich sent the brigade of Bobich, consisting of 2973 men and 20 cannons through Rád and Kosd to encircle the imperial troops from Vác, but his infantry mistook the way in the fog, and moved towards Penc (to East instead of West), and with this his troops failed to appear in the battle.[20] In the last moment before the battle Georg von Ramberg, the commander of the imperial troops got ill, and because of this, the command was taken by Major General Christian Götz.[21] Windisch-Grätz advised him to retreat without fight to west to the Garam (in Slovakian Hron) river, if he faces superior troops.[22] The troops commanded by Götz had not fought from the middle of February, being occupied to move here and there in Northern Hungary, so from this point of view the battle hardened Hungarian troops were in advantage.[23]

Battle

On the rainy day of 10th April, Damjanich started at 9 o'clock the attack against Vác, from the south, on the Pest-Vác road, because the poachy morning fields were impossible to use them for battle. The road which led to Vác, crossed the stone bridge on the Gombás creek, so Götz installed his infantry on it.[24]

In this moment Götz was unaware of a serious Hungarian attack, thinking only about numerically inferior troops, which do a demonstration, thus when he saw that the Hungarians install their cannons, he strengthened only his vanguards by sending his 2. battalion to position themselves along the Gombás creek, between the railway embankment and the Danube.[25] The battle started with an artillery duel, which lasted a several hours. Damjanich installed the Czillich and Leiningen brigades at left, and the Kiss and Kökényessy brigades at the right wing. He was waiting for the brigade of Bobich to complete the encirclement of the imperial troops, but in vain. In the meanwhile Götz understood that he faces a numerically superior army, and at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, decided to start the retreat from the town.[26] He ordered to his brigade commanders to withdraw from the city, but he wanted to hold the bridge until his troops will be to enough distance from the Hungarians, to be safe.[27]

Seeing that it is no sign of the Bobich brigade in the enemy rear, Damjanich lost his patience, ordered to his infantry to charge the bridge, while his artillery was shooting continuously. Götz seeing that his troops start to retreat from the foreground of the bridge, because of the huge pressure from the Hungarians, he rode forward, screaming: "Advance, do not retreat!" In that moment he was hit by a shell splinter on his forehead, while his horse was taken down by at last ten bullets. The Austrian soldiers held him while he was falling down, and took their wounded commander in the military boarding school from Vác.[28]

The Wysocki division was the first to charge the bridge, but their attacks, which they repeated a several times crumbled in the fusillade of the imperial kaiserjägers.[29] After their failure, came the 3th and the 9th battalions, which were among the most renowned Hungarian units, to try, but the soldiers were not willing to risk their lives in a seemingly hopeless task. Than came to the scene the commander of the 3. battalion, Major Károly Földváry, the hero of the Battle of Tápióbicske, took the flag of his battalion, and rode on the bridge with it, under the hail of bullets the enemy soldiers who occupied the half of the bridge. His horse was shot dead in seconds, but he went back to his soldiers, took another horse and rode up the bridge again, and the same thing happened: the horse fell down under him in a second, but he remained unharmed. In that moment the imperial officer who was commanding the volley was so astonished by his recklessness, that he forgot to order his soldiers to shoot, and in that moment the soldiers of the Hungarian 9th battalion arrived on the bridge and swept away the Austrian resistance.[30] After that the other Hungarian battalions too crossed the bridge, and in heavy street fights pushed the imperials out of the city.[31] During these street fights the Hungarians arrived to the building of the military boarding school, where the wounded Götz lied, and defended by the Bianchi infantry regiment, occupied it after heavy fights, and found the Austrian commander in it, taking him prisoner with many enemy soldiers.[32] The imperial troops which fought by the railway embankment withstood an hour after the Hungarians crossed the bridge, preventing an encirclement from east of the imperial troops, than they also retreated in heavy fights.[33]

The imperial forces, now led by Major General Felix Jablonowski, retreated in heavy street fights from Vác, heading towards Verőce.[34] The Austrian commander installed some artillery, consisting of a two cannon batteries, one of 12, the other of 6 fonts, and a rocket battery, with which he supported his troops withdraw, managing to retreat his troops in order.[35]

Aftermath

One of the interns of the Polish Legion took care of Götz's wounds. On 11 April Görgey arrived to Vác, and one of the first things he made, was to visit Götz, and ask, how is he feeling, but this, because of his wound, loose his ability to talk, and could not respond, and was dying. His last wish was to be buried together with his ring. He received the extreme unction by a Hungarian army chaplain, who prayed next to him, until he dyed.[36] Götz was buried on 12th April, his coffin being carried by Hungarian soldiers on their shoulders accompanied by military music and drumbeat, in front of the Hungarian soldiers and the prisoner Austrians. The coffin was descended to the grave by three generals: Görgey, György Klapka, Damjanich and a staff officer.[37] In 1850 Götz's widow showed gratitude for the nursing and respect paid to her husband from his enemies, by donating 2,000 forints to the military boarding school in which her husband had spent his last hours.[38]

From tactical point of view, although they had lost their commander, the imperial defeat was not heavy, because the army could retreat in order.[39] After the battle Damjanich was dissatisfied with the performance of some Hungarian commanders and units, believing that this battle could had been brought much more success than it had actually. The choleric, fast decision taking general criticized the slowness of the cautious Klapka, who if he would had moved faster, he would had arrived on time on the battlefield, General József Nagysándor, the commander of the cavalry, for the slowliness of the pursuit of the enemy after the battle.[40] He also wanted to decimate the Polish Legion because they run away after the first attack, but the arriving Görgey prevented this.[41] Damjanich was angry of the unexploited positive situations in this battle and the other battles which were fought before in the Spring Campaign (Tápióbicske, Isaszeg), and he taught that the other commanders and troops are responsible for these.[42]

With the victory at Vác, the Hungarian army opened its way towards the Garam river.[43] After the battle the imperial command in Pest continued to believe that the Hungarian main forces were still before the capital.[44] This was caused by the fact that in the Battle of Vác only one corps participated, which made the commander to think that the rest of the Hungarian army had not yet arrived in Pest.[45] When Windisch-Grätz seemed to finally grasp what was happening in reality, wanting to make a powerful attack at 14 April against the Hungarians at Pest, than to cross the Danube at Esztergom, and cut the way of the army which was marching towards Komárom, his corps commanders, General Franz Schlik and Lieutenant Field Marshal Josip Jelačić refused to obey to his commands, so his plan, which could cause serious problems to the Hungarian armies, was not realized.[46] Windisch-Grätz, to hold the Hungarian advancement in the west towards Komárom, sent an order to Lieutenant General Ludwig von Wohlgemuth to stop them with the reserve corps formed from the dispensable imperial troops from Vienna, Styria, Bohemia and Moravia. These troops would suffer a heavy defeat on 19 April by the Hungarian army in the Battle of Nagysalló, and with that the Hungarians opened the way to the besieged Komárom.[47] But when these events took palace, Windisch-Grätz was not in Hungary, because in the meanwhile, on 12 April he was relieved from the high command of the imperial troops in Hungary, by the emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria. In his place Feldzeugmeister Ludwig von Welden was appointed.[48]

Notes

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 236.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 282.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 283.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 283.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 285.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 286.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 283.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 288.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 232–236.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 233.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 233.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 287.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 233.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 288.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 288.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 288.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 288–289.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Tragor 1984, pp. 148.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 235.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 289.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 289.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 289.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 235.

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 235.

- ↑ Pusztaszeri 1984, pp. 290.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 284.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285–289.

- ↑ Hermann 2001, pp. 285–289.

Sources

- Hermann (ed), Róbert (1996). Az 1848–1849 évi forradalom és szabadságharc története ("The history of the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Videopont. p. 464. ISBN 963-8218-20-7.

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 ("Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Freedom 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. p. 430. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (2001). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc hadtörténete ("Military History of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Korona Kiadó. p. 424. ISBN 963-9376-21-3.

- Pusztaszeri, László (1984). Görgey Artúr a szabadságharcban ("Artúr Görgey in the War of Independece") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. p. 784. ISBN 963-14-0194-4.

- Tragor, Ignác (1984). Vác története 1848-49-ben ("History of Vác in 1848–49") (in Hungarian). Vác: Váci Múzeum Egyesület. p. 544.