Bicameralism

| Legislature |

|---|

| Chambers |

| Parliament |

| Parliamentary procedure |

| Types |

| Legislatures by country |

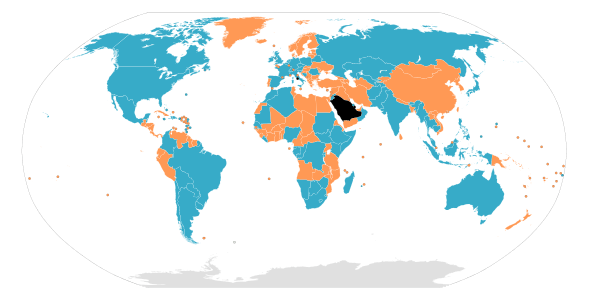

A bicameral legislature is one in which the legislators are divided into two separate assemblies, chambers or houses. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all of the members deliberate and vote as a single group, and from some legislatures which have three or more separate assemblies, chambers or houses. As of 2015, somewhat less than half of the world's national legislatures are bicameral.[1]

Often, the members of the two chambers are elected or selected using different methods, which vary from country to country. Enactment of primary legislation often requires a concurrent majority, the approval of a majority of members in each of the chambers of the legislature. However, in many Westminster system parliaments, the house to which the executive is responsible can overrule the other house.

Bicameralism is an essential and defining feature of the classical notion of mixed government.

Theory of bicameral congress

Although the ideas on which bicameralism are based can be traced back to the theories developed in ancient Sumer and later ancient Greece, ancient India, and Rome, recognizable bicameral institutions first arose in Medieval Europe where it was associated with separate representation of different estates of the realm. For example, one house would represent the aristocracy, and the other would represent the commoners.[2]

The Founding Fathers of the United States also favoured a bicameral legislature. The idea was to have the Senate be wealthier and wiser. Benjamin Rush saw this though, and noted that, "this type of dominion is almost always connected with opulence." The Senate was created to be a stabilising force, elected not by mass electors, but selected by the State legislators. Senators would be more knowledgeable and more deliberate—a sort of republican nobility—and a counter to what Madison saw as the "fickleness and passion" that could absorb the House.[2]

He noted further that the "use of the Senate is to consist in its proceeding with more coolness, with more system and with more wisdom, than the popular branch". Madison's argument led the Framers to grant the Senate prerogatives in foreign policy, an area where steadiness, discretion, and caution were deemed especially important".[2] The Senate was chosen by state legislators, and senators had to possess a significant amount of property in order to be deemed worthy and sensible enough for the position. In fact, it was not until the year 1913 that the 17th Amendment was passed, which "mandated that Senators would be elected by popular vote rather than chosen by the State legislatures".[2]

As part of the Great Compromise, they invented a new rationale for bicameralism in which the Senate would have states represented equally, and the House would have them represented by population.

In subsequent constitution making, federal states have often adopted bicameralism, and the solution remains popular when regional differences or sensitivities require more explicit representation, with the second chamber representing the constituent states. Nevertheless, the older justification for second chambers—providing opportunities for second thoughts about legislation—has survived.

Growing awareness of the complexity of the notion of representation and the multifunctional nature of modern legislatures may be affording incipient new rationales for second chambers, though these do generally remain contested institutions in ways that first chambers are not. An example of political controversy regarding a second chamber has been the debate over the powers of the Canadian Senate or the election of the Senate of France.[3]

The relationship between the two chambers varies; in some cases, they have equal power, while in others, one chamber is clearly superior in its powers. The first tends to be the case in federal systems and those with presidential governments. The latter tends to be the case in unitary states with parliamentary systems.

There are two streams of thought: Critics believe bicameralism makes meaningful political reforms more difficult to achieve and increases the risk of gridlock—particularly in cases where both chambers have similar powers—while proponents argue the merits of the "checks and balances" provided by the bicameral model, which they believe help prevent the passage into law of ill-considered legislation.

Types

Federal

Some countries, such as Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Canada, Germany, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Russia, Switzerland, Nigeria, and the United States, link their bicameral systems to their federal political structure.

In the United States, Australia, and Mexico, for example, each state is given the same number of seats in one of the houses of the legislature, despite the total population of each state — it is designed to ensure that smaller states are not overshadowed by larger states, which may have more representation in the other house of the legislature.

In the United States both houses of the U.S. Congress, the House of Representatives and the Senate, are co-equals and there is no "upper" or "lower" chamber and no hierarchical relationship between them, although the House is colloquially (and incorrectly) referred to as the lower house, and the Senate the upper house. This is due to their original location in the two-story building that was to house them.[4]

In Canada, the country as a whole is divided into a number of Senate Divisions, each with a different number of Senators, based on a number of factors. These Divisions are Quebec, Ontario, Western Provinces, and the Maritimes, each with 24 Senators, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, each with 1 Senator, and Newfoundland and Labrador has 6 Senators, making for a total of 105 Senators.

Senators in Canada are not elected by the people but are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister. The Senate does not originate most legislation (although a small fraction of government bills are introduced in the Senate and Senators may introduce private members' bills in the same way as MPs) but acts as a chamber of revision almost always passing legislation approved by the House of Commons, made up of Members of Parliament (MPs) who are elected. The Senate must pass legislation before it becomes law and can therefore act as a wise facilitator or engage in filibuster. The Senate does not have to endure the accountability and scrutiny of parliamentary elections. Therefore, the bicameral structure of Canadian parliament is more de jure than de facto.

In the German, Indian, and Pakistani systems, the upper houses (the Bundesrat, the Rajya Sabha, and the Senate respectively) are even more closely linked with the federal system, being appointed or elected directly by the governments or legislatures of each Land, State, or Province. (This was also the case in the United States before the 17th Amendment.) The Indian Upper House does not have the states represented equally, but on the basis of their population. In the German Bundesrat, the various Länder have between three and six votes; thus, while the less populated states have a lower weight, they still have a stronger voting power than would be the case in a system based purely on population, as the most populous Land currently has about 27 times the population of the least populous. In German legal doctrine, the Bundesrat is technically not considered a second chamber. Strictly speaking, the Bundesrat is another constitutional body and only the directly elected Bundestag is considered to be the parliament.

There are also instances of bicameralism in countries that are not federations, but which have upper houses with representation on a territorial basis. For example, in South Africa, the National Council of Provinces (and before 1997, the Senate) has its members chosen by each Province's legislature. "

In Spain the Spanish Senate functions as a de facto territorial-based upper house, and there has been some pressure from the Autonomous Communities to reform it into a strictly territorial chamber.

The European Union maintains a bicameral legislative system which consists of the European Parliament, which is elected in general elections on the basis of universal suffrage, and the Council of the European Union which consists of members of the governments of the Member States which are competent for the relevant field of legislation. Although the European Union is not considered a state, it enjoys the power to legislate in many areas of politics; in some areas, those powers are even exclusively reserved to it.

Aristocratic and post-aristocratic

In a few countries, bicameralism involves the juxtaposition of democratic and aristocratic elements.

The best known example is the British House of Lords, which includes a number of hereditary peers. The House of Lords represents a vestige of the aristocratic system which once predominated in British politics, while the other house, the House of Commons, is entirely elected. Over the years, there have been proposals to reform the House of Lords, some of which have been at least partly successful — the House of Lords Act 1999 limited the number of hereditary peers (as opposed to life peers, appointed by Her Majesty on the advice of the Prime Minister ) to 92, down from around 700. Of these 92, one is the Earl Marshal, a hereditary office always held by the Duke of Norfolk, one is the Lord Great Chamberlain, a hereditary office held by turns, currently by the Marquess of Cholmondeley, and the other 90 are elected by all sitting peers. Hereditary peers elected by the House to sit as representative peers sit for life; when a representative peer dies, byelections occur to fill the vacancy. The ability of the House of Lords to block legislation is curtailed by the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949. Peers can introduce bills except Money Bills, and all legislation must be passed by both Houses of Parliament. If it is not passed within two sessions, the House of Commons can override the Lords delay by invoking the Parliament Act. Certain pieces of legislation however must be approved by both Houses and are not able to be forced through by the Commons under the Parliament Act. This includes any bill which would extend the time length of a Parliament, private bills, bills which are sent to the House of Lords less than one month before the end of a session, and bills which originate in the House of Lords.

Life Peers are appointed either by recommendation of the Appointment Commission; the independent body that vets non-partisan peers, typically from academia, business or culture, or by Dissolution Honour, which takes place at the end of every Parliamentary term and leaving MPs may be offered a seat to keep their institutional memory. It is traditional for a peerage to be offered to every outgoing Speaker of the House of Commons.[5]

Further reform of the Lords has been proposed; however, reform is not supported by many. Members of the House of Lords all have an aristocratic title, or are from the Clergy. 26 Archbishops and Bishops of the Church of England sit as Lords Spiritual, being the Archbishop of Canterbury, Archbishop of York, the Bishop of London, the Bishop of Durham, the Bishop of Winchester and the next 21 longest-serving Bishops. It is usual that retiring Archbishops, and certain other Bishops, are appointed to the Crossbenches and given a life peerage. Until 2009, 12 Lords of Appeal in Ordinary sat in the House as the highest court in the land; they subsequently became justices of the newly created Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. At present, 786 people sit in the House of Lords, with 92 Hereditary, 26 being Bishops or Archbishops (the Lords Spiritual) and the rest being Life Peers. Membership is not fixed and decreases only on the death of a life peer.

Another example of aristocratic bicameralism was the Japanese House of Peers, abolished after World War II and replaced with the present House of Councillors.

Unitary States

Many bicameral countries like the Netherlands, the Philippines, the Czech Republic, the Republic of Ireland and Romania are examples of bicameral systems existing in unitary states. In countries such as these, the upper house generally focuses on scrutinizing and possibly vetoing the decisions of the lower house.

On the other hand, in Italy the Parliament consists of two chambers that have the same role and power: the Senate (Senate of the Republic, commonly considered the upper house) and the Chamber of Deputies (considered the lower house).

In some of these countries, the upper house is indirectly elected. Members of France's Senate, Ireland's Seanad Éireann are chosen by electoral colleges consisting of members of the lower house, local councillors, the Taoiseach, and graduates of selected universities, while the Netherlands' Senate is chosen by members of provincial assemblies (which in turn are directly elected).

Norway had a kind of semi-bicameral legislature with two chambers, or departments, within the same elected body, the Storting. These were called the Odelsting and Lagting and were abolished after the general election of 2009. According to Morten Søberg, there was a related system in the 1798 constitution of the Batavian Republic.[6]

In Hong Kong, members of the unicameral Legislative Council returned from the democratically elected geographical constituencies and partially-democratic functional constituencies are required to vote separately since 1997 on motions, bills or amendments to government bills not introduced by the government. The passage of these motions, bills or amendments to government bills requires double majority in both groups simultaneously. (Before 2004, when elections to the Legislative Council from the Election Committee was abolished, members returned through the Election Committee vote with members returned from geographical constituencies.) The double majority requirement does not apply to motions, bills and amendments introduced by the government.

Subnational entities

In some countries with federal systems, individual states (like those of the United States, Australia and a few States of India) may also have bicameral legislatures. Only three such states, Nebraska in the US, Queensland in Australia and Bavaria in Germany have later adopted unicameral systems. Canadian provinces had all their upper houses abolished.

Argentina

In Argentina, eight provinces have bicameral legislatures, with a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies: Buenos Aires, Catamarca, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Mendoza, Salta, San Luis (since 1987) and Santa Fe. Córdoba and Tucumán changed to unicameral systems in 2001 and 2003 respectively.

Australia

In Australian states, the lower house was traditionally elected based on the one-vote-one-value principle, whereas the upper house was partially appointed and elected, with a bias towards country voters and landowners. In Queensland, the appointed upper house was abolished in 1922, while in New South Wales there were similar attempts at abolition, before the upper house was reformed in the 1970s to provide for direct election. Nowadays, the upper house is elected using proportional voting and the lower house through preferential voting, except in Tasmania, where proportional voting is used for the lower house, and preferential voting for the upper house.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Legislature of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, is a bicameral legislative body. It consists of two chambers. The House of Representatives has 98 delegates, elected for four-year terms by proportional representation. The House of Peoples has 58 members, 17 delegates from among each of the constituent peoples of the Federation, and 7 delegates from among the other peoples.[7] Republika Srpska, the other entity, has a unicameral parliament, known as the National Assembly.[8]

Germany

The German Land of Bavaria had a bicameral legislature from 1946 to 1999, when the Senate was abolished by a referendum amending the state's constitution. The other 15 Länder have used a unicameral system since their founding.

India

Seven Indian States, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar, Jammu-Kashmir, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh, have bicameral Legislatures, these are called legislative councils (Vidhan Parishad), one third of whom are elected every two years, there are graduate constituencies (members elected exclusively by graduates), teachers constituencies (members elected exclusively by teachers), municipal constituencies (members elected exclusively by Mayors and council members of the city Governments). From 1956 to 1958 the Andhra Pradesh Legislature was unicameral. In 1958, when the Legislative Council was formed, it became bicameral until 1 June 1985 when it was abolished. This continued until March 2007 when the Legislative Council was reestablished and elections were held for its seats. Since then the Andhra Pradesh Legislature has become once again bicameral. In Tamil Nadu, a resolution was passed on 14 May 1986 and the Legislative Council was dissolved on 1 Nov 1986. Again on 12 April 2010, a resolution was passed to bring it back bicameral, but became unsuccessful in 2011.

Russia

Under Soviet regime regional and local Soviets were unicameral. After the adoption of 1993 Russian Constitution bicameralism was introduced in some regions. Bicameral regional legislatures are still technically allowed by federal law but this clause is dormant now. The last region to switch from bicameralism to unicameralism was Sverdlovsk Oblast in 2012.

United States

During the 1930s, the Legislature of the State of Nebraska was reduced from bicameral to unicameral with the 43 members that once comprised that state's Senate. One of the arguments used to sell the idea at the time to Nebraska voters was that by adopting a unicameral system, the perceived evils of the "conference committee" process would be eliminated.

A conference committee is appointed when the two chambers cannot agree on the same wording of a proposal, and consists of a small number of legislators from each chamber. This tends to place much power in the hands of only a small number of legislators. Whatever legislation, if any, the conference committee finalizes must then be approved in an unamendable "take-it-or-leave-it" manner by both chambers.

During his term as Governor of the State of Minnesota, Jesse Ventura proposed converting the Minnesotan legislature to a single chamber with proportional representation, as a reform that he felt would solve many legislative difficulties and impinge upon legislative corruption. In his book on political issues, Do I Stand Alone?, Ventura argued that bicameral legislatures for provincial and local areas were excessive and unnecessary, and discussed unicameralism as a reform that could address many legislative and budgetary problems for states.

Reform

Arab political reform

A 2005 report on democratic reform in the Arab world by the US Council on Foreign Relations co-sponsored by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright urged Arab states to adopt bicameralism, with upper chambers appointed on a 'specialized basis'. The Council claimed that this would protect against the 'Tyranny of the majority', expressing concerns that without a system of checks and balances extremists would use the single chamber parliaments to restrict the rights of minority groups.

In 2002, Bahrain adopted a bicameral system with an elected lower chamber and an appointed upper house. This led to a boycott of parliamentary elections that year by the Al Wefaq party, who said that the government would use the upper house to veto their plans. Many secular critics of bicameralism were won around to its benefits in 2005, after many MPs in the lower house voted for the introduction of so-called morality police.

Romania

A referendum on introducing a unicameral Parliament instead of the current bicameral Parliament was held in Romania on 22 November 2009. The turnout rate was 50.95%, with 77.78% of "Yes" votes for a unicameral Parliament.[9] This referendum had a consultative role, thus requiring a parliamentary initiative and another referendum to ratify the new proposed changes.

Ivory Coast

A referendum on a new constitution will be held on October 30, 2016. The constitution draft would create a bicameral Parliament instead of the current unicameral. The Senate is expected to represent the interests of territorial collectivities and Ivoirians living abroad. Two thirds of the Senate is to be elected at the same time as the general election. The remaining one third is appointed by the president elect.[10]

Examples

Current

Historical

| | Rigsdagen | Under the constitution Rigsdagen was created, with two houses, an upper and lower house. However, after the 1953 referendum, both Rigsdagen and the Landsting was abolished, making the Folketing the sole chamber of the parliament. | |

| Landsting (Upper house) | Folketing (Lower house) | ||

| | Parliament of the Hellenes | The Senate as an upper chamber was established by the Greek Constitution of 1844, of the Kingdom of Greece, and was abolished by the Greek Constitution of 1864. The Senate was reestabished by the republican Constitution of 1927, which establishing the Second Hellenic Republic and was disestablished by the restoration of the Kingdom of Greece at 1935. | |

| Gerousia (Senate) | Vouli (Chamber of Deputies) | ||

| | National Assembly | Under the first constitution (first republic, 1948–52), the National Assembly was unicameral. The second and third constitutions (first republic, 1952–60) regulated the National Assembly was bicameral and consisted of the House of Commons and the Senate, but only the House of Commons was established and the House of Commons could not pass a bill to establish the Senate. During the short-lived second republic (1960–61), the National Assembly became practically bicameral, but it was overturned by the May 16 coup. The National Assembly has been unicameral since its reopen in 1963. | |

| Senate | House of Commons | ||

| | Parliament | Until 1950, the New Zealand Parliament was bicameral. It became unicameral in 1951, but the name "House of Representatives" has been retained. | |

| Legislative Council | House of Representatives | ||

| | Cortes | During the period of Constitutional Monarchy, the Portuguese Parliament was bicameral. The lower house was the Chamber of Deputies and the upper house was the Chamber of Peers (except during the 1838-1842 period, where a Senate existed instead). With the replacement of the Monarchy by the Republic in 1910, the Parliament continued to be bicameral with a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate existing until 1926. | |

| Chamber of Deputies | Chamber of Peers | ||

| | Parliament | It was established with the Turkish constitution of 1961 and abolished with the Turkish constitution of 1982, although it did not exist between 1980 and 1982 either as a result of the 1980 coup d'état in Turkey. | |

| National Assembly | Senate of the Republic | ||

| | Congress | ||

| Chamber of Deputies | Senate | ||

References

- ↑ "IPU PARLINE database: Structure of parliaments". www.ipu.org. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- 1 2 3 4 The Constitutional Background - House of Representatives archives

- ↑ (French) Liberation.fr, Sénat, le triomphe de l'anomalie

- ↑ http://www.apstudynotes.org/us-history/topics/philadelphia-convention/

- ↑ How do you become a Member of the House of Lords? - UK Parliament. Parliament.uk (2010-04-21). Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- ↑ Minerva.as

- ↑ Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- ↑ The National Assembly of the Republic of Srpska

- ↑ Referendum turnout 50.95%. 77.78 said YES for a unicameral Parliament, 88.84% voted for the decrease in the number of Parliamentarians, Official results from the Romanian Central Electoral Commission

- ↑ "Innovations of the Draft Constitution of Cote d'Ivoire: Towards hyper-presidentialism?".

- ↑ http://constitution.org.np/userfiles/constitution%20of%20nepal%202072-en.pdf

External links

- Noncontemporaneous Lawmaking: Can the 110th Senate Enact a Bill Passed by the 109th House?, 16 Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol'y 331 (2007).

- Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl, Against Mix-and-Match Lawmaking, 16 Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol'y 349 (2007).

- Defending the (Not So) Indefensible: A Reply to Professor Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl, 16 Cornell J.L. & Pub. Pol'y 363 (2007).