Big Sur

| Big Sur | |

|---|---|

| Region of California | |

|

The Big Sur Coast | |

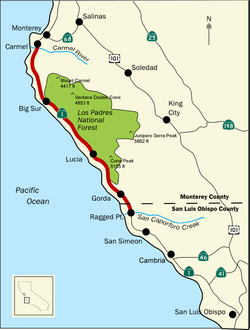

Map of Big Sur | |

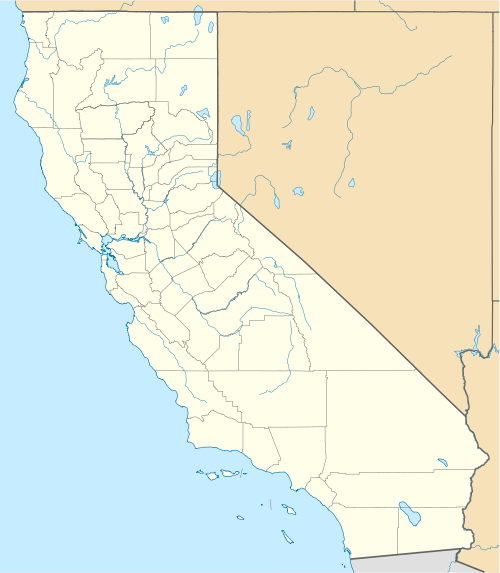

Big Sur Location in California | |

| Coordinates: 36°06′27″N 121°37′33″W / 36.1075°N 121.625833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

Big Sur, described as the "greatest meeting of land and water in the world,"[1] is an undeveloped, lightly populated, unincorporated region on California's Central Coast where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. The coast is frequently praised for its rugged coastline and mountain views. As the "longest and most scenic stretch of undeveloped coastline in the continental United States,"[2] it has been described it as a "national treasure that demands extraordinary procedures to protect it from development,"[3] and "one of the most beautiful coastlines anywhere in the world, an isolated stretch of road, mythic in reputation."[4] Big Sur's Cone Peak at 5,155 feet (1,571 m) is only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[5] The stunning views make Big Sur a popular tourist destination.

The region is protected by the Big Sur Local Coastal Program which preserves the region as "open space, a small residential community, and agricultural ranching."[6] Approved in 1981, it is one of the most restrictive local use programs in the state,[7] and is widely regarded as one of the most restrictive documents of its kind anywhere.[8] The program protects viewsheds from the highway and many vantage points, and restricts the density of development to one unit per acre in tourist areas or one dwelling per 10 acres (4.0 ha) in the far south. About 60% of the coastal region is owned by a government or private agency that does not allow any development. The majority of the interior region is part of the Los Padres National Forest, the Ventana Wilderness, Silver Peak Wilderness, or Fort Hunter Liggett.

The region remained one of the most isolated areas of California and the United States until, after 18 years of construction, the Carmel-San Simeon Highway was completed in 1937. The region does not have specific boundaries, but is generally considered to include the 76 miles (122 km) segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel River south to San Carpoforo Creek near San Simeon and the entire Santa Lucia range between the rivers.[5] The interior region is uninhabited, while the coast remains relatively isolated and sparsely populated with about 1,000 year-round residents and relatively few visitor accommodations.

The original Spanish-language name for the unexplored mountainous terrain south of Monterey, the capital of Alta California, was "el país grande del sur" meaning, "the big country of the south." It was Anglicized by English-speaking settlers as Big Sur.

Location

Big Sur is not an incorporated town, but an area without formal boundaries on the Central Coast of California.[9] The boundaries of the region have gradually expanded over time. Esther Pfeiffer Ewoldson, who was born in 1904 and was a granddaughter of Big Sur pioneers Micheal and Barbara Pfeiffer, wrote that the region extended from the Little Sur River 23 miles (37 km) south to Slates Hot Springs. Members of the Harlen family who homesteaded the Lucia region 9 miles (14 km) south of Slates Hot Springs, said that Big Sur was "miles and miles to the north of us."[10]:6 Prior to the construction of Highway 1, the residents on the south coast had little contact with the residents to the north of them.[10] Later on the northern border was extended as far north as Malpaso Creek, 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of Carmel River. Many current descriptions of the area refer to the 76 miles (122 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south well past Lucia to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County.[11]

Because the vast majority of visitors only see Big Sur's dramatic coastline, some consider the eastern border of Big Sur to be the coastal flanks of the Santa Lucia Mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland.[12] Visitors sometimes mistakenly believe that Big Sur refers to the small community of buildings and services near Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, known to locals as Big Sur Village.[13] Author and Big Sur historian Jeff Norman considered Big Sur to extend inland to include the watersheds that drain into the Pacific Ocean.[14] Others include the vast inland areas comprising the Los Padres National Forest, Ventana Wilderness, Silver Peak Wilderness, and Fort Hunter Liggett about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucia Mountains.[5]

The region is relatively difficult to access. Prior to 1937 when the coast highway was completed, the only way to travel the coast was a horse and wagon road, first built in about 1853 as far as Palo Colorado Road. The "Old Coast Road" was later expanded south to the Post Ranch near Sycamore Canyon, and then expanded further south. The southern portion is known as the "Coast Ridge Road."[5] Both were often unusable during and after winter storms.[15] When the region was first settled by European immigrants in 1853, it was the United States' "last frontier."[16]

Etymology

The Portolá expedition who first explored the Spanish colony of Alta California were forced to bypass the inaccessible coast and travel around the region, inland through the San Antonio and Salinas Valley, before arriving at Monterey Bay, where they founded Monterey and named it their capital.[17] They referred to the vast, relatively unexplored, coastal region to the south el país grande del sur, meaning "the big country of the south". This was often shortened to el sur grande.[18][19] Other sources report that the region was simply called "el sur" (the south), and the two major rivers El Rio Grande del Sur and El Rio Chiquito del Sur.[14]:7

When English-speaking immigrants settled the region, they Anglicized the Spanish name to "Big Sur". The locals petitioned the United States Post Office in Washington D.C. to use the name Big Sur, and the rubber stamp was returned in in 1915, cementing the name in place.[10]:8[14]:7

Popularity

The coast is the "longest and most scenic stretch of undeveloped coastline in the continental United States."[2] The Big Sur region has been described as a "national treasure that demands extraordinary procedures to protect it from development."[3] The New York Times described it as "one of the most stunning meetings of land and sea in the world."[20] The Washington Times described it as "one of the most beautiful coastlines anywhere in the world, an isolated stretch of road, mythic in reputation."[4]

Highway 1 was named the most popular drive in California in 2014 by American Automobile Association. The section of Highway 1 running through Big Sur is widely considered as one of the most scenic driving routes in the United States, if not the world.[21][22]

The views are one reason that Big Sur was ranked second among all United States destinations in TripAdvisor's 2008 Travelers' Choice Destination Awards.[23] The Big Sur coast has attracted as residents notable bohemian writers and artists including Robinson Jeffers, Henry Miller, Edward Weston, Richard Brautigan, Hunter S. Thompson, Emile Norman, and Jack Kerouac. Novelist Herbert Gold described Big Sur as "one of the grand American retreats for those who nourish themselves with wilderness."[24]

Despite and because of its popularity, the region is heavily protected to preserve the rural and natural character of the land. The Big Sur Local Coastal Program, approved by Monterey County Supervisors in 1981, states the region is meant to be an experience that visitors transit through, not a destination. For that reason, development of all kinds is severely restricted.[25]

Attractions

.jpg)

Although some Big Sur residents catered to adventurous travelers in the early twentieth century,[10]:10 the modern tourist economy began when Highway 1 opened the region to automobiles, and only took off after World War II-era gasoline rationing ended in the mid-1940s. In 1978, about 1.5 million visitors are estimated to have visited the Big Sur Coast.[26] Most of the 3 to 4 million tourists who currently visit Big Sur each year never leave Highway 1, because the adjacent Santa Lucia mountain range is one of the largest roadless areas near a coast in the contiguous United States. The highway winds along the western flank of the mountains mostly within sight of the Pacific Ocean, varying from near sea level up to a thousand-foot sheer drop to the water. The highway includes a large number of vista points allowing motorists to stop and admire the landscape.[27]

Among the places that draw visitors are the counter-culture Esalen Institute, the luxury Ventana Inn, the Nepenthe Restaurant, built around the house Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth bought to celebrate their six-month-long affair, and far from the coast in the Las Padres forest, the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center.[24]

Local activities

Besides sightseeing from the highway, Big Sur offers hiking, mountain climbing, and other outdoor activities. There are a number of state and federal lands and parks, including McWay Falls at Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park, one of only two waterfalls on the Pacific Coast that plunge directly into the ocean. The waterfall is located near the ruins of a grand stone cliffside house built in 1940 by Lathrop and Hélène Hooper Brown that was the region's first electrified home.

Another notable landmark is Point Sur Lighthouse, the only complete nineteenth century lighthouse complex open to the public in California.[28]

Beaches

There are a few small, scenic beaches that are popular for walking, but usually unsuitable for swimming because of unpredictable currents, frigid temperatures, and dangerous surf.[29]

The beach at Garrapata State Park is sometimes rated as the best beach in Big Sur. Visitors can view sea otters, sea lions, seals and migrating whales from the beach. It is barely visible from the Highway One.[29]

Pfieffer Beach is accessible by driving 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of the entrance to Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park on Highway 1, and turning west on the unmarked Sycamore Canyon Road. The beach is at the end of the road. The wide sandy expanse with views of a scenic arch rock offshore is a favorite among local residents. It is sometimes confused with the beach at Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park to the south.[29]

In the south, Sand Dollar Beach is the longest stretch of beach in Big Sur. It is popular with hikers and photographers for its views of nearby bluffs. The beach is 25 miles (40 km) south of the Big Sur village on Highway 1. A steep staircase leads down to the beach from the highway.[29]

Limited services

The land use restrictions that preserve Big Sur's natural beauty also mean that visitor accommodations are limited, often expensive, and places to stay fill up quickly during the busy summer season. There are no urban areas, although three small clusters of gas stations, restaurants, and motels are often marked on maps as "towns": Posts in the Big Sur River valley, Lucia, near Limekiln State Park, and Gorda, on the southern coast. There are fewer than 300 hotel rooms on the entire 90 mi (140 km) stretch of Highway 1 between San Simeon and Carmel. Lodging include a few cabins, motels, and campgrounds, and higher-end resorts.

Most lodging and restaurants are clustered in the Big Sur River valley, where Highway 1 leaves the coast for a few miles and winds into a redwood forest, protected from the chill ocean breezes and summer fog. One of the places to stay, Deetjen's Big Sur Inn, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[30] Room rates as of 2016 were from $125 for a room with a shared bathroom in the Hayloft Building to $290 for a room in The Stokes Building.[31] The Post Ranch Inn, a Forbes Travel Guide Four-Star hotel, charges an average of $1,200 per night, although breakfast is included.[32]

Nineteen eating places of various sizes are found along the highway, cumulatively seating about 1,100 people.[33] The Nepenthe Restaurant charges $17.50 for a vegetarian burger and $31.00 for a chicken dinner.[34] The Fernwood Grill charges $10.25 for burrito,[35] and the Big Sur Deli has sandwiches under $7.00.[36]

There are nine small grocery stores, three gas stations, a few gift shops, and no chain hotels, supermarkets, or fast-food outlets, and no plans to add facilities or shopping.[37][38][39] The gas station in Gorda has one of the highest prices in the United States.[40][41] Depending on the carrier, there is mobile phone service along much of the highway, except for south of Lucia.[19]

Short term rental controversy

In 2015, Monterey County began considering how to deal with the issue of short term rentals brought on by services such as Airbnb. They agreed to allow rentals as long as the owners paid the Transient Occupancy Tax. In 1990, there were about 800 housing units in Big Sur, about 600 of which were single family dwellings.[38][42] There are currently an estimated 100 short term rentals available.[43]

Many residents of Big Sur object to the rentals. They claim short term rentals violate the Big Sur Local Use Plan which prohibits establishing facilities that attract destination traffic. Short term rentals also remove scarce residences from the rental market and are likely to drive up demand and the cost of housing. About half of the residents of Big Sur rent their residences.[43]

The Big Sur coastal land use plan states:

The significance of the residential areas for planning purposes is that they have the capacity, to some extent, to accommodate additional residential demand. Unlike the larger properties or commercial centers, they are not well suited for commercial agriculture, commercial, or visitor uses (author’s emphasis); use of these areas, to the extent consistent with resource protection, should continue to be for residential purposes.[44]

As of 2016, the county was conducting hearings and gathering input towards making a decision about short-term rentals on the Big Sur coast.[45] Susan Craig, Central Coast District Manager of the California Coastal Commission, has offered her opinion that short term rentals are appropriate within Big Sur.[46]

Flora and fauna

The many climates of Big Sur result in a great biodiversity, including many rare and endangered species such as the wild orchid Piperia yadonii, which is found only on the Monterey Peninsula and on Rocky Ridge in the Los Padres forest. Arid, dusty chaparral-covered hills exist within easy walking distance of lush riparian woodland.

Southern limit of Redwood trees

The mountains trap most of the moisture out of the clouds; fog in summer, rain and snow in winter. This creates a favorable environment for coniferous forests, including the southernmost habitat of the coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), which grows only on lower coastal slopes that are routinely fogged in at night. Some redwood trees were logged in the early 20th century but many inaccessible locations were never logged, and in 2008 scientist J. Michael Fay published a map of the old growth redwoods based on his transect of the entire redwood range.[47]

Rare species

The rare Santa Lucia fir (Abies bracteata) is found only in the Santa Lucia mountains. A common "foreign" species is the Monterey pine (Pinus radiata), which was uncommon in Big Sur until the late 19th century, though its major native habitat is only a few miles upwind on the Monterey Peninsula, when many homeowners began to plant the quick-growing tree as a windbreak. There are many broadleaved trees as well, such as the tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus), coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia), and California bay laurel (Umbellularia californica). In the rain shadow, the forests disappear and the vegetation becomes open oak woodland, then transitions into the more familiar fire-tolerant California chaparral scrub.

Wildlife

.jpg)

The region was historically populated by grizzly bears who regularly preyed on livestock until the early 20th century. The European settlers used to pay bounties to have them killed.[10]:4 The Pfeifer family would fill a bait ball of swine entrails with strychnine and hang it from a tree. The last Grizzly Bear in Monterey County was seen in 1941 on the Cooper Ranch near the mouth of the Little Sur River.[48] :21 In the past 25 years, American black bears have been sighted in the area, likely expanding their range from southern California and filling in the ecological niche left when the Grizzly bear was exterminated.[5]:261

The Big Sur River watershed provides habitat for mountain lion, deer, fox, coyotes and non-native wild boars. The upstream river canyon is characteristic of the Ventana Wilderness region: steep-sided, sharp-crested ridges separating valleys.[49] Because most of the upper reaches of the Big Sur River watershed are within the Los Padres National Forest and the Ventana Wilderness, much of the river is in pristine condition.

- Steelhead

The California Department of Fish and Game says the river is the "most important spawning stream for steelhead" on the Central Coast.[50] and that it "is one of the best steelhead streams in the county."[51]:166 The Big Sur River is a key habitat within the Central California Steelhead distinct population segment which is listed as threatened.[52][53]

A U.S. fisheries service report estimates that the number of trout in the entire south-central coast area—including the Pajaro River, Salinas River, Carmel River, Big Sur River, and Little Sur River—have dwindled from about 4,750 fish in 1965 to about 800 in 2005.

Numerous fauna are found in the Big Sur region. Among amphibians the California giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus) is found here, which point marks the southern extent of its range.[54]

- California Condor

The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) is a critically endangered species that was near extinction when the remaining wild birds were captured. A captive breeding program was begun in 1987. After some success, a few birds were released in 1991 and 1992 in Big Sur, and again in 1996 in Arizona near the Grand Canyon.[55]

In 1997, the Ventana Wildlife Society began releasing captive-bred California Condor in Big Sur. The birds take six years to mature before they can produce offspring, and a nest was discovered in a redwood tree in 2006.[56][57] This was the first time in more than 100 years in which a pair of California condors had been seen nesting in Northern California.[58] The repopulation effort has been successful in part because a significant portion of the birds' diet includes carcasses of large sea creatures that have washed ashore, which are unlikely to be contaminated with lead, the principal cause of the bird's mortality.[59]

As of July 2014, the Ventana Wildlife Society managed 34 free-flying condors.[60] There were part of a total population of 437 condors spread over California, Baja California and Arizona, of which 232 are wild birds and 205 are in captivity.[61]

Marine protected areas

Point Sur State Marine Reserve and Marine Conservation Area and Big Creek State Marine Reserve and Big Creek State Marine Conservation Area are marine protected areas offshore from Big Sur. Like underwater parks, these marine protected areas help conserve ocean wildlife and marine ecosystems.

Fire impact

Fire plays a key role in the ecology of the upper slopes of the Big Sur region's mountains where chaparral dominates the landscape.[62] Native Americans burned chaparral to promote grasslands for textiles and food.[63] In the lower elevations and canyons, the California Redwood is often found. Its thick bark, along with foliage that starts high above the ground, protect the species from both fire and insect damage, contributing to the coast redwood's longevity.[64] Fire appears to benefit redwoods by removing competitive species. A 2010 study compared post-wildfire survival and regeneration of redwood and associated species. It concluded that fires of all severity increase the relative abundance of redwood and higher-severity fires provide the greatest benefit.[65]

In modern history, fires are known to have burned the Big Sur area multiple times. In 1885, 1894, and 1898 fires burned without any effort by the few local residents to put them out, except to save their buildings.[66] In 1903, a fire burned for three months, the result of an unextinguished campfire. In 1906, a fire that began in Palo Colorado Canyon from the embers of a campfire burned for 35 days, scorching an estimated 150,000 acres (61,000 ha), and was finally extinguished by the first rainfall of the season.[67]

In recent history, the area has been struck by the Marble Cone fire in 1977, the Rat Creek Gorda Complex fire in 1985, the Kirk Complex fire in 1999, the Basin Complex fire in 2008, and the Soberanes Fire in 2016.[68]

- Basin Complex Fire

The Basin Complex Fire forced an eight-day evacuation of Big Sur and the closure of Highway 1, beginning just before the July 4, 2008 holiday weekend.[69] The fire, which burned over 130,000 acres (53,000 ha), represented the largest of many lightening-caused wildfires that had broken out throughout California during the same period.[70] Although the fire caused no loss of life, it destroyed 27 homes, and the tourist-dependent economy lost about a third of its expected summer revenue.[71][72]

- Soberanes Fire

The Soberanes Fire, started by an illegal campfire in the Garrapata Creek watershed, burned around the Big Sur community. Coast residents east of Highway 1 were required to evacuate for short periods, and Highway 1 was shut down at intervals over several days to allow firefighters to conduct backfire operations. As of 2016 it burned 57 homes in the Garrapata and Palo Colorado Canyon areas. A bulldozer operator was killed when his equipment overturned during night operations. Visitors avoided the area and tourism revenue was impacted for several weeks.[73]

History

Native Americans

Three tribes of Native Americans—the Ohlone, Esselen, and Salinan—are the first known people to have inhabited the area. The Ohlone, also known as the Costanoans, are believed to have lived in the region from San Francisco to Point Sur. The Esselen lived in the area between Point Sur south to Big Creek, and inland including the upper tributaries of the Carmel River and Arroyo Seco watersheds. The Salinan lived from Big Creek south to San Carpoforo Creek.[74] Archaeological evidence shows that the Esselen lived in Big Sur as early as 3500 BC, leading a nomadic, hunter-gatherer existence.[75][76]

The aboriginal people inhabited fixed village locations, and followed food sources seasonally, living near the coast in winter to harvest rich stocks of otter, mussels, abalone, and other sea life. In the summer and fall, they traveled inland to gather acorn and hunt deer.[77] The native people hollowed mortar holes into large exposed rocks or boulders which they used to grind the acorns into flour. These can be found throughout the region. Arrows were of made of cane and pointed with hardwood foreshafts.[77] The tribes also used controlled burning techniques to increase tree growth and food production.[5]: 269–270

The population was limited as the Santa Lucia Mountains made the area relatively inaccessible and long-term habitation a challenge. Their natives who lived in the Big Sur area are estimated from a few hundred to a thousand or more.[78][79]

Spanish exploration and settlement

The first Europeans to see Big Sur were Spanish mariners led by Juan Cabrillo in 1542, who sailed up the coast without landing. Two centuries passed before the Spaniards attempted to colonize the area. In 1769, an expedition led by Gaspar de Portolá became the first Europeans known to have explored Big Sur when they entered the area in the south near San Carpoforo Canyon.[5]: 272 Daunted by the sheer cliffs and difficult topography, his party avoided the area and traveled far inland through the Salinas Valley.

When the Spanish colonized the region beginning in 1770 and established the California missions, they baptized and forced the native population to labor at the missions. While living at the missions, the aboriginal population was exposed to unknown diseases like smallpox and measles for which they had no immunity, devastating the Native American population and their culture. Many of the remaining Native Americans assimilated with Spanish and Mexican ranchers in the nineteenth century.[5]: 264–267

In 1909, forest supervisors reported that three Indian families still lived within what was then known as the Monterey National Forest. The Encinale family of 16 members and the Quintana family with three members lived in the vicinity of The Indians (now known as Santa Lucia Memorial Park west of Ft. Hunger Liggett). The Mora family consisting of three members was living to the south along the Nacimiento-Ferguson Road.[80]

Spanish ranchos

Along with the rest of California, Big Sur became part of Mexico when it gained independence from Spain in 1821. Parts of the Big Sur region were included in land grants given by Mexican governors José Figueroa and Juan Alvarado.

- Rancho Tularcitos

Rancho Tularcitos, 26,581-acre (107.57 km2) of land, was granted in 1834 by Governor José Figueroa to Rafael Goméz.[81] It was located in upper Carmel Valley along Tularcitos Creek.[82]

- Rancho Milpitas

Rancho Milpitas was a 43,281-acre (175.15 km2) land grant given in 1838 by governor Juan Alvarado to Ygnacio Pastor.[83] The grant encompassed present day Jolon.[84] When Pastor obtained title from the Public Land Commission in 1875, Faxon Atherton immediately purchased the land. By 1880, the James Brown Cattle Company owned and operated Rancho Milpitas and neighboring Rancho Los Ojitos. William Randolph Hearst's Piedmont Land and Cattle Company acquired the rancho in 1925.[85] In 1940, in anticipation of the increased forces required in World War II, the U.S. War Department purchased the land from Hearst to create a troop training facility known as the Hunter Liggett Military Reservation.[86]

- Rancho El Sur

On July 30, 1834, Figueroa granted Rancho El Sur, two square leagues of land totalling 8,949-acres (3,622 ha), to Juan Bautista Alvarado.[87]:21[88] The grant extended between the Little Sur River and what is now called Cooper Point.[89][90] Alvarado later traded Rancho El Sur for the more accessible Rancho Bolsa del Potrero y Moro Cojo in the northern Salinas Valley, owned by his uncle by marriage, Captain John B.R. Cooper.[91]

- Rancho San Jose y Sur Chiquito

In 1839, Alvarado granted Rancho San Jose y Sur Chiquito, also about two square leagues of land totalling 8,876-acre (35.92 km2), to Marcelino Escobar, a prominent official of Monterey.[92] The grant was bounded on the north by the Carmel River and on the south by Palo Colorado Canyon.[93]

In 1848, two days after the discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill, Mexico ceded California to the United States as a result of the Mexican-American War.

First survey

During the first survey of the coast conducted in 1886, the surveyor reported:

The country between the shore-line and the Coast Range of mountains, running parallel with the shore-line from San Carpojoro to Point Sur is probably the roughest piece of coast-line on the whole Pacific coast of the United States from San Diego to Cape Flattery.The highest peaks of the crest of the coast range are located at an average distance from the coast of three and a half miles [5.6 km]. In this distance they rise to elevations of from three thousand six hundred to five thousand feet [1,100 to 1,500 m] above the sea-level. From San Carpoforo Creek to Pfeiffer's Point, a distance of 5 miles (8.0 km), the shore-line is iron-bound coast with no possible chance of getting from the hills to the shore-line and back except at the mouths of the creeks and at such places as Coxe's Hole and Slate's Hot Springs, where there are short stretches of sandy and rocky beaches from fifty to one hundred yards [meters] in length. In many places the sea bluffs are perpendicular, and rise from one thousand to one thousand five hundred feet [300 to 460 m] above the sea. The country is cut up by deep cañons [canyons], walled in with high and precipitous bluffs. These canyons are densely wooded with redwood, oak, and yellow and silver pine timber.

The redwood trees are from three to six feet [0.91 to 1.83 m] in diameter and from one hundred to one hundred and fifty feet high [30 to 46 m]. The oaks and pines are of the same average dimensions. Beautiful streams of clear cold water, filled with an abundance of salmon or trout, are to be found in all the cartons. The spurs running from the summits of the range to the ocean bluffs are covered with a dense growth of brush and scattering clumps of oak and pine timber. The chaparral is very thick, and in many places grows to a height of ten or fifteen feet [3-5 m]... The spurs, slopes, and canons are impenetrable...[94][95]

Homesteaders

The first known European settler in Big Sur was George Davis, who in 1853 claimed a tract of land along the Big Sur River. He built a cabin near the present day site of the beginning of the Mount Manuel Trail,[5]:326 just above the location of a cabin later built by John Bautista Rogers Cooper. Born John Rogers Cooper, he was a Yankee born in the British Channel Islands who arrived in Monterey in 1823.[96] To marry and obtain land, he became a Mexican citizen, converted to Catholicism, and was given a Spanish name at his baptism. He married native American Encarnacion Vallejo and acquired considerable land including Rancho El Sur, on which he built a cabin in April or May 1861.[97] The Cooper Cabin is the oldest surviving structure in Big Sur.[98] In 1868, native Americans Manual and Florence Innocenti bought Davis' cabin and land for $50. The second European settlers were the Pfeiffer family from France. Michael Pfeiffer and his wife and four children arrived in Big Sur in 1869 with the intention of settling on the south coast. After reaching Sycamore Canyon, they found it to their liking and decided to stay.[5]:326

After passage of the federal Homestead Act in 1862, a few hardy settlers were drawn by the promise of free 160-acre (65 ha) parcels. The first to file a land patent was Micheal Pfeiffer on January 20, 1883, who claimed two sections of land he already resided on near and immediately north of the mouth of Sycamore Canyon.[99] They had six more children later on.

Other settlers included William F. Notley, who homesteaded at the mouth of Palo Colorado Canyon in 1891. He began harvesting tanoak bark from the canyon, a lucrative source of income at the time. Notley's Landing is named after him. Many other local sites retain names from settlers during this period: Bottcher, Swetnam, Gamboa, Pfeiffer, Post, Partington, Ross, and McWay are a few of the place names.

Industrial era and gold rush

From the 1860s through the start of the 20th century, lumberers cut down most of the readily accessible coast redwoods. Along with industries based on tanoak bark harvesting, gold mining, and limestone processing, the local economy provided more jobs and supported a larger population than it does today.

In the 1880s, a gold rush boom town named Manchester sprang up at Alder Creek in the mountains east of present-day Gorda, at 35°52′48″N 121°23′31″W / 35.880°N 121.392°W.[100][101] The town boasted a population of 200, four stores, a restaurant, five saloons, a dance hall, and a hotel, but it was abandoned soon after the start of the 20th century and burned to the ground in 1909.[10][102]

The 30-mile (48 km) trip from Monterey to the Pfeiffer Ranch could take three days by wagon. It was a rough road that ended in present-day Big Sur Village and could be impassible in winter. Local entrepreneurs built small boat landings like what is known today as Bixby Landing at a few coves along the coast from which supplies could be received and products could be shipped from schooners via a cable hoist.[103] None of these landings remain today, and few other signs of this brief industrial period are visible. The rugged, isolated terrain kept out all but the sturdiest and most self-sufficient settlers.[104] Travelers further south had to follow a horse trail that connected the various homesteaders along the coast.[105]

Before Highway 1

Prior to the construction of Highway 1, the California coast south of Carmel and north of San Simeon was one of the most remote regions in the state, rivaling at the time nearly any other region in the United States for its difficult access.[15] It remained largely an untouched wilderness until early in the twentieth century.[2]

After the brief industrial boom faded, the early decades of the 20th century passed with few changes, and Big Sur remained a nearly inaccessible wilderness. As late as the 1920s, only two homes in the entire region had electricity, locally generated by water wheels and windmills.[5]: 328[10]:64 Most of the population lived without power until connections to the California electric grid were established in the early 1950s.[15]

Before the Carmel-San Simeon Highway was completed, settlement was primarily concentrated near the Big Sur River and present-day Lucia, and individual settlements along a 25 miles (40 km) stretch of coast between the two.[15]

Highway 1

Construction

During the 1890s, Dr. John L. D. Roberts, a physician and land speculator who had founded Seaside, California and resided on the Monterey Peninsula, was summoned on April 21, 1894 to assist treating survivors of the wreck of the S.S. Los Angeles (originally USRC Wayanda),[106] which had run aground near the Point Sur Light Station about 25 miles (40 km) south of Carmel. The ride on horseback took him 3 1⁄2 hours, and he became convinced of the need for a road along the coast to San Simeon, which he believed could be built for $50,000.[106]

In 1897, Roberts traveled the entire stretch of rocky coast from Carmel to San Simeon, and photographed the land, becoming the first surveyor of the route.[107] He initially promoted the road for allowing access to a region of spectacular beauty. Roberts was only successful in gaining attention to the project when State Senator Elmer S. Rigdon, a member of the California Senate Committee on Roads and Highways, promoted the military necessity of defending California's coast.[106] A $1.5 million bond issue was placed on the ballot, but construction was delayed by World War I.

The state first approved building Route 56, or the Carmel – San Simeon Highway,[108] to connect Big Sur to the rest of California in 1919. Federal funds were appropriated and in 1921 voters approved additional state funds. San Quentin Prison set up three temporary prison camps to provide unskilled convict labor to help with road construction. One was set up by Little Sur River, one at Kirk Creek and a third was later established in the south at Anderson Creek. Inmates were paid 35 cents per day and had their prison sentences reduced in return. Locals, including writer John Steinbeck, also worked on the road.[107] The road necessitated construction of 33 bridges, the largest of which was the Bixby Creek Bridge. Six more concrete arch bridges were built between Point Sur and Carmel, and all were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.[106]

Construction required extensive excavation utilizing steam shovels and explosives, cutting into exposed promontories and filling canyons. Many members of the original families were upset by the damage to the environment caused by the construction.[44] Some construction debris were pushed downslope into the ocean.[109] Prior to designation of the offshore marine sanctuary, CalTrans routinely pushed slide debris into the nearshore littoral environment.

Completion

After 18 years of construction, aided by New Deal funds during the Great Depression, the paved two-lane road was completed and opened on June 17, 1937.[110] The road was initially called the Carmel-San Simeon Highway, but was better known as the Roosevelt Highway, honoring the current President (Franklin Delano Roosevelt). Actual cost of the construction was around $10 million. The road was frequently closed for extended periods during the winter, making it a seasonal route. During World War II, night-time blackouts were ordered as a precaution against Japanese attack.[105]

Improvements

Prior to the construction of Highway 1, the California coast south of Carmel and north of San Simeon was one of the most inaccessible regions in the state, rivaling nearly any other region in the United States for its remoteness.[15]

The route was incorporated into the state highway system and redesignated as Highway 1 in 1939. In 1940, the state contracted for "the largest installation of guard rail ever placed on a California state highway", calling for 12 miles (19 km) of steel guard rail and 3,649 guide posts along 46.6 miles (75.0 km) of the road.[105] After World War II and gas rationing ended, tourism and travel boomed along the coast. When Hearst Castle opened in 1958, a huge number of tourists also flowed through Big Sur. The road was declared the first State Scenic Highway in 1965, and in 1966 the first lady, Lady Bird Johnson, led the official designation ceremony at Bixby Creek Bridge.[105] The route was designated as an All American Road by the U.S. Government.[106]

Aside from Highway 1, the only access to Big Sur is via the winding, precipitous, 24.5 miles (39.4 km) long Nacimiento-Fergusson Road, which passes through Fort Hunter Liggett and connects to Mission Road in Jolon.[12]

Economic impacts

The opening of Highway 1 dramatically altered the local economy. Monterey County gained national attention for its early conservation efforts when it successfully prevented construction of a service station billboard. The landmark court case before the California Supreme Court in 1962 affirmed the county's right to ban billboards and other visual distractions on Highway 1.[111] The case secured to local government the right to use its police power for aesthetic purposes.[112]

Highway 1 has been closed on more than 55 occasions due to damage due from landslides, mudslides, erosion, and fire.[113]:2-2 In April 1958, torrential rains caused flood conditions through out Monterey County and Highway 1 in Big Sur was closed in numerous locations due to slides.[114] A series of storms in the winter of 1983 caused four major road-closing slides between January and April, including a large slide near Pfeiffer Burns State Park which closed the road for more than a year.[113]:2–10 In 1998, about 40 different locations on the road were damaged by El Niño storms, including a major slide 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Gorda that closed the road for almost three months.[109] In March 2011, a 40 feet (12 m) section of Highway 1 just south of the Rocky Creek Bridge collapsed, closing the road for several months until a single lane bypass could be built.[115][116] The state replaced that section of road with a viaduct that wraps around the unstable hillside.[12] On January 16, 2016, the road was closed for portions of a day due to a mudslide near Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park[117] and in the summer of 2016, the road was closed on several occasions due to the Soberanes Fire.

Transportation issues

Highway 1 is at or near capacity much of the year. The primary transportation objective of the Big Sur Coastal Land Use plan is to maintain Highway 1 as a scenic two-lane road and to reserve most remaining capacity for the priority uses of the act.[44]

Public Transportation is available to and from Monterey on Monterey-Salinas Transit. The summer schedule operates from Memorial Day to Labor Day three times a day, while the winter schedule only offers transport on weekends. The route is subject to interruption due to wind and severe inclement weather.[118]

Big Sur land use

The majority of the Big Sur coast and interior are owned by the California State Department of Parks and Recreation, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Army, U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, the Big Sur Land Trust, and the University of California. Approximately two-thirds of the Big Sur coastal area, totalling about 500,000 acres (200,000 ha), extending from the Carmel River in the north to San Simeon and the San Luis Obispo County line at San Carpóforo Canyon in the south, are preserved under various federal, state, county, and private arrangements.[9][38][44] As of 2016, if public acquisitions now contemplated or in progress are completed, approximately 60% of the coast will be publicly owned.[38][42]

Local conservation plan

The first master plan for the Big Sur coast was written in 1962 by architect and part-time local resident Nathaniel Owings. In 1977 a small group of local Big Sur residents were appointed by Monterey County to the Big Sur Citizens’ Advisory Committee. Committee members met with Big Sur residents and county administrators to draft a new land use plan.[9] They wrote the Big Sur Local Coastal Program with the goal to conserve scenic views and the unparalleled beauty of the area. They developed the plan over four years which included several months of public hearings and discussion, including considerable input from the residents of Big Sur. It states that region is to be preserved as "open space, a small residential community, and agricultural ranching."[6] The plan was approved in 1981 and is one of the most restrictive local use programs in the state,[7][119] and is widely regarded as one of the most restrictive documents of its kind anywhere.[8]

The land use plan bans all development west of Highway 1 with the exception of the Big Sur Valley. The plan states,

Recognizing the Big Sur coast's outstanding scenic beauty and its great benefit to the people of the State and the Nation, it is the County's objective to preserve these scenic resources in perpetuity and to promote, wherever possible, the restoration of the natural beauty of visually degraded areas.The County's basic policy is to prohibit all future public or private development visible from Highway 1 and major public viewing areas.[120]

Major public viewing areas include not only highways, but beaches, parks, campgrounds, and major trails, with a few exceptions.[7] It also protects views of Mount Pico Blanco from the Old Coast Road.[44] It allows limited amounts of additional commercial development, but only in four existing areas: Big Sur Valley, Lucia, Pacific Valley, and Gorda.[120][3]

The key provisions of the Big Sur Local Coastal Program that generated the most controversy set density requirements for future building. In tourist areas, the limit is one living unit per acre. West of Highway 1, density is limited to one unit per 2.5 acres (1.0 ha), and east of the highway to one unit per 5 acres (2.0 ha). In established communities like Palo Colorado and the Big Sur Valley, only one living unit per 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) is permitted. South of Big Sur Valley, the limit is set to one unit per (5 acres (2.0 ha), and in the far south of the region, only one unit per 10 acres (4.0 ha) are allowed.[9]

The plan establishes a system in which the owner of a property that cannot be developed under the rules can transfer that right to another piece of land where building is permitted.[37]

Mining

Mount Pico Blanco is topped by a distinctive white limestone cap, visible from California's Highway One.[121] The Granite Rock Company of Watsonville, California has owned the mineral rights to 2,800 acres (1,100 ha) near and at the summit of Pico Blanco Mountain since 1963. Limestone is a key ingredient in concrete and Granite Rock applied for a permit in 1980 from the U.S. Forest Service to begin excavating a 5 acres (2.0 ha) quarry on the South face of Pico Blanco within the National Forest boundary.[122]

After the Forest Service granted the permit, the California Coastal Commission required Graniterock to apply for a coastal development permit in accordance with the requirements of the California Coastal Act. Granite Rock filed suit claiming that the Coastal Commission permit requirement was preempted by the Forest Service review. When Granite Rock prevailed in the lower courts, the Coastal Commission appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which in a historic 5-4 decision, found in favor of the commission.[123]

By this time Granite Rock's permit had expired. In 2010, the company's president stated that he believes that at some point the company will be allowed to extract the limestone in a way that doesn't harm the environment.[123][124] As of 2016, they still own the land.

Gold mining in the Los Burros District was a focal point of mining activity during the 1880s. There are also limited oil and gas reserves located offshore on the Outer Continental Shelf.[44]

Real estate

Due to development restrictions, real estate prices are high. As of 2016, the median price of property is $1,813,846, and the average price is $3,942,371. The average home sold is 1,580 square feet (147 m2) and has 2.39 bedrooms. The median lot size is 436,086 square feet (40,513.7 m2), or just over 10 acres (4.0 ha).[125] Much of the land along the coast is privately owned or is part of the state park system, while the vast Los Padres National Forest, the Ventana Wilderness, and Fort Hunter Liggett Military Reservation encompass most of the inland areas.

About 76% of the local population is dependent on the hospitality industry. Due to the shortage of housing and the high cost of rents, some of them have to move out of the area and commute 50 miles (80 km) or more to their work.[126]

As of 2016 there are about 1,100 private land parcels on the Big Sur Coast. These are from less than an acre to several thousands of acres. Approximately 790 parcels are undeveloped. Many of the developed parcels more than one residence or commercial building on them. Residential areas include Otter Cove, Garrapata Ridge and the adjacent Rocky Point, Garrapata and Palo Colorado Canyons, Bixby Canyon, Pfeiffer Ridge and Sycamore Canyon, Coastlands, Partington Ridge, Burns Creek, Buck Creek to Lime Creek, Plaskett Ridge, and Redwood Gulch.[38]

Small parcels of 2.5 acres (1.0 ha) or less are generally located near the highway, including Palo Colorado Canyon, Garrapata Redwood, Rocky Point, Big Sur Valley, Coastlands and Partington. These areas have the greatest number of developed parcels.[38]

Coastal trail

In 1972, California voters passed Proposition 20 which called for establishing a coastal trail system.[127] It stipulated that "a hiking, bicycle, and equestrian trails system be established along or near the coast" and that "ideally the trails system should be continuous and located near the shoreline." The California Coastal Act of 1976 requires local jurisdictions to identify an alignment for the California Coastal Trail in their Local Coastal Programs.[128] In 2001, California legislators passed SB 908 which gave the Coastal Conservancy responsibility for completing the trail.[129]

In Monterey County, the trail is being developed in two sections: the Big Sur Trail and the Monterey Bay Sanctuary Trail.[127] In 2007, the Coastal Conservancy began to develop a master plan for the 75 miles (121 km) stretch of coast through Big Sur from near Ragged Point in San Luis Obispo County to the Carmel River.[130] A coalition of Big Sur residents began developing a master plan to accommodate the interests and concerns of coastal residents,[127] but progress on an official trail stalled.

The coastal trail plan is intended to be respectful of the private landowner's rights.[128] One of the largest private land holdings along the coast is El Sur Ranch. It extends about 6 miles (9.7 km) along Highway 1, from near the Point Sur Lighthouse to the mouth of the Little Sur River at Hurricane Point, and it reaches 2.5 miles (4.0 km) up the Little Sur valley to the border of the Los Padre National Forest.[131] The landowner Jim Hill supports the trail, but his land is already crossed by two public routes, Highway 1 and the Old Coast Highway. He is opposed to another public right-of-way through the ranch.[132] In 2008, Representative Sam Farr from Carmel told attendees at a meeting in Big Sur that "I don't think you're going to see an end-to-end trail anytime in the near future." He said, "The regulatory hassle is unbelievable. It's like we're building an interstate freeway."[127] Within Monterey County, about 20 miles (32 km) of the trail would cross private lands.[133]

The acquisition of lands by the Big Sur Land Trust and others has created a 70 miles (110 km) long wildland corridor that begins at the Carmel River and extends southward to the Hearst Ranch in San Luis Obispo County. From the north, the wild land corridor is continuous through Palo Corona Ranch, Point Lobos Ranch, Garrapata State Park, Joshua Creek Ecological Preserve, Mittledorf Preserve, Glen Deven Ranch, Brazil Ranch, Los Padres National Forest, and the Ventana Wilderness.[134] Many of these lands are distant from the coast, and the coastal trail plan calls for placing the trail, "Wherever feasible, ...within sight, sound, or at least the scent of the sea. The traveler should have a persisting awareness of the Pacific Ocean. It is the presence of the ocean that distinguishes the seaside trail from other visitor destinations."[128]

As an alternative to the trail called for by the act, hikers have adopted a route that utilizes existing roads and inland trails. The trail currently follows State Highway One and the Old Coast Road from Bixby Bridge. The trail south of Bixby Creek enters Brazil Ranch, which requires permission to enter. From Brazil Ranch the trail drops back to Highway One at Andrew Molera State Park. From Highway One, the trail then follows the Coast Ridge Road from the Ventana Inn area to Kirk Creek Campground. The trail then moves inland and follows the Cruikshank and Buckeye trails on the Santa Lucia Mountain ridges to the San Luis Obispo County line.[135][136]

Artists and writers

Henry Miller

In the early to mid-20th century, Big Sur's relative isolation and natural beauty began to attract writers and artists, including Robinson Jeffers, Henry Miller, Edward Weston, Richard Brautigan, Hunter S. Thompson, Emile Norman, and Jack Kerouac. Jeffers was the first, arriving in Big Sur with his bride Una in 1913.[137] Beginning in the 1920s, his poetry introduced the romantic idea of Big Sur's wild, untamed spaces to a national audience, which encouraged many of the later visitors. In the posthumously published book Stones of the Sur, Carmel landscape photographer Morley Baer later combined his classical black and white photographs of Big Sur with some of Jeffers' poetry.

Henry Miller lived in Big Sur for 20 years, from 1944 to 1962. His home was a wooden cabin that had been owned by his friend Emil White. His 1957 essay/memoir/novel Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch described the joys and hardships that came from escaping the "air conditioned nightmare" of modern life. The Henry Miller Memorial Library is a nonprofit bookstore and arts center that opened in 1981 as a tribute to the legendary writer. It is a gathering place for locals and has become the focal point of individuals with a literary mind,[138] a cultural center devoted to Miller's life and work, and a popular attraction for tourists.[139]

Other writers

Hunter S. Thompson worked as a security guard and caretaker at a resort in Big Sur Hot Springs for eight months in 1961, just before the Esalen Institute was founded at that location. While there, he published his first magazine feature in the nationally distributed Rogue (men's) magazine, about Big Sur's artisan and bohemian culture.

Jack Kerouac spent a few days in Big Sur in early 1960 at fellow poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti's cabin in the woods, and wrote a novel, Big Sur, based on his experience there. Big Sur acquired a bohemian reputation with these newcomers. Henry Miller recounted that a traveler knocked on his door, looking for the "cult of sex and anarchy."[140] Apparently finding neither, the disappointed visitor returned home. Miller is referenced in Brautigan's A Confederate General at Big Sur, in which a pair of young men attempt the idyllic Big Sur life in small shacks and are variously plagued by flies, low ceilings, visiting businessmen with nervous breakdowns, and 2,452 tiny frogs whose loud singing keeps everyone awake.

Places of contemplation

Big Sur also became home to centers of study and contemplation—a Catholic monastery, the New Camaldoli Hermitage in 1958, the Esalen Institute. Esalen hosted many figures of the nascent "New Age", and in the 1960s, played an important role in popularizing Eastern philosophies, the "human potential movement", and Gestalt therapy in the United States.

Film setting

The area's increasing popularity and incredible beauty soon brought the attention of Hollywood. Orson Welles and his wife at the time, Rita Hayworth, bought a Big Sur cabin on impulse during a trip down the coast in 1944. They never spent a single night there, and the property is now the location of a popular restaurant, Nepenthe.[142]

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton starred in the 1965 film The Sandpiper, featuring many location shots of Big Sur, and a dance party scene on a soundstage built to resemble Nepenthe. The Sandpiper was one of the few major studio motion pictures filmed in Big Sur, and perhaps the only one to identify real Big Sur locales by name as part of the plot. A DVD, released in 2006, includes a Burton-narrated short film about Big Sur, quoting Robinson Jeffers poetry.

Another film based in Big Sur was the 1974 Zandy's Bride, starring Gene Hackman and Liv Ullman.[143] An adaptation of The Stranger in Big Sur by Lillian Bos Ross, the film portrayed the 1870s life of the Ross family and their Big Sur neighbors.

Big Sur Folk Festival

Nancy Carlen, a friend of Joan Baez, organized a weekend seminar at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur in June 1964 titled "The New Folk Music." Sunday afternoon they invited all the neighbors for a free, open performance. This became the first festival.[144]

From 1964 to 1971, the Big Sur Folk Festival featured a line up of emerging and established artists including Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, The Beach Boys, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, Country Joe McDonald, John Sebastian, Arlo Guthrie, Dorothy Morrison & the Edwin Hawkins Singers, Julie Payne, and Richard and Mimi Farina. The festival was held yearly on the grounds of the Esalen Institute, except for 1970, when it was held at the Monterey County Fairgrounds.

The concerts were small events emphasising quality and atmosphere over publicity and commercial profit. Even when then well-known acts like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young or the Beach Boys performed, the event was purposefully kept small with no more than a few thousand in attendance.[145]

Big Sur International Marathon

The Big Sur Marathon is an annual marathon that begins south of Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park and ends at the Crossroads Shopping Center in Carmel, California. The marathon was established in 1986 and attracts about 4,500 participants annually.[146]

Geography

Climate

Big Sur typically enjoys a mild climate year-round, with a sunny, dry summer and fall, and a cool, wet winter. Coastal temperatures range from the 50s at night to the 70s by day (Fahrenheit) from June through October, and in the 40s to 60s from November through May. Farther inland, away from the ocean's moderating influence, temperatures are much more variable. The weather varies widely due to the influence of the jagged topography, creating many microclimates. This is one of the few places on Earth where redwoods grow in close proximity to cacti.

Temperatures

The record maximum temperature was 102 °F (38.9 °C) on June 20, 2008, and the record low was 27 °F (−2.8 °C), recorded on December 21, 1998, and January 13, 2007. Average annual precipitation at the state park headquarters is 41.94 inches (1,065 mm). The wettest calendar year on record was 1983, when it rained 88.85 inches (2,257 mm). The driest year on record is 1990, with only 17.90 inches (455 mm). In January 1995 it rained a record 26.47 inches (672 mm). More than 70 percent of the rain falls from December through March. The summer is generally dry. Snowfall is rare on the coast, but is common in the winter months on the higher ridges of the Santa Lucia Mountains.[147]

Geology

The Santa Lucia Mountains rise suddenly from the Pacific Ocean, creating a steep coastline. The mountains contain some of the most complex geology in California. The range is made up of rock originating in seafloor volcanoes, ancient mountains, stream beds, and seafloor sediment. The region is laced with a series of earthquake fault lines. Some geologists believe that the rock underlying the mountains was originally located 1,800 miles (2,900 km) to the south, near the southern end of the present-day Sierra Nevada Mountains, and may have been buried as deep as 14 miles (23 km) beneath the surface.[5]:7–8 The rock is believed to be from 15 to 21 million years old and had been moved north by transform motion along the San Andreas Fault system.

The Palo Colorado-San Gregorio fault system transitions onshore at Doud Creek, 7 miles south of Point Lobos, exposing the western edge of the Salinian block. Stream canyons frequently follow fault the north-westerly trending fault lines, rather than descending directly to the coast. The Salinian block is immediately south of the Monterey Submarine Canyon, one of the largest submarine canyon systems in the world, which is believed to have been an ancient outlet for the Colorado River.[148]:14

The Palo Colorado-San Gregorio fault transitions from shore to sea at Doud Creek, about 7 miles (11 km) south of Point Lobos.[148] The region is also traversed by the Sur-Hill fault, which is noticeable at Pfeiffer Falls in Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park. The 40 feet (12 m) waterfall were formed when the stream flowed over the hard gneiss of the Salinian block and encountered the softer Santa Margarita Sandstone. The falls were formed when the softer sandstone was worn away.[5]:325 The interior canyons are typically deep and narrow, and even in the summer sunshine only reaches many of the canyon bottoms for a few hours. The land is mostly steep, rocky, semi-arid except for the narrow canyons, and inaccessible. The Little Sur River canyon is characteristic of the Ventana Wilderness region: steep-sided, sharp-crested ridges separating valleys.[49] At the mouth of the Little Sur river are some of the largest sand dunes on the Big Sur coast.[5]:355

Marine influence

Along with much of the central and northern California coast, Big Sur frequently has dense fog in summer. The summer fog and summer drought have the same underlying cause: a massive, stable seasonal high pressure system that forms over the north Pacific Ocean. The high pressure cell inhibits rainfall and generates northwesterly air flow. These prevailing summer winds from the northwest drive the ocean surface water slightly offshore (through the Ekman effect) which generates an upwelling of colder sub surface water. The water vapor in the air contacting this cold water condenses into fog.[5]: 33–35 The fog usually moves out to sea during the day and closes in at night, but sometimes heavy fog blankets the coast all day. Fog is an essential summer water source for many Big Sur coastal plants. Most plants cannot take water directly out of the air, but the condensation on leaf surfaces slowly precipitates into the ground like rain.

Rain

The Santa Lucia range rises to more than 5,800 ft (1760 m), and the amount of rainfall greatly increase as the elevation rises and cools the air. At Pfeiffer–Big Sur State Park on the coast, rainfall averaged about 43 in. (109 cm) annually from 1914 to 1987. Scientists estimate that about 90 in. (230 cm) falls on average near the ridge tops. But actual totals vary considerably.[5]

Monterey County maintains a remote rain gauge for flood prediction on Mining Ridge at 4,000 ft (1200 m) near Cone Peak. The gauge frequently receives more rain than any gauge in the San Francisco Bay Area.[5][149] During the winter of 1982–1983, it rained more than 178 in. (452 cm) but the total is unknown because the rain gauge failed at that point. In 1975–1976, it rained only 15 in. (39 cm) at Pfeiffer–Big Sur State Park, compared to 85 in. (216 cm) in 1982–1983. Rainfall amounts decrease sharply inland away from the coast.[5]

| Climate data for Big Sur | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

85 (29) |

87 (31) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

101 (38) |

100 (38) |

100 (38) |

90 (32) |

75 (24) |

102 (39) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 59.7 (15.4) |

61.5 (16.4) |

63.4 (17.4) |

68.3 (20.2) |

72.6 (22.6) |

75.9 (24.4) |

75.6 (24.2) |

77.3 (25.2) |

77.1 (25.1) |

73.2 (22.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

59.9 (15.5) |

69.1 (20.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 42.9 (6.1) |

43.1 (6.2) |

43.4 (6.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

45.8 (7.7) |

48.3 (9.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

50.0 (10) |

50.3 (10.2) |

47.9 (8.8) |

44.9 (7.2) |

41.9 (5.5) |

46.0 (7.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

37 (3) |

41 (5) |

40 (4) |

39 (4) |

36 (2) |

28 (−2) |

27 (−3) |

27 (−3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 9.10 (231.1) |

8.65 (219.7) |

6.49 (164.8) |

3.11 (79) |

1.09 (27.7) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.03 (0.8) |

0.05 (1.3) |

0.42 (10.7) |

2.03 (51.6) |

4.85 (123.2) |

7.62 (193.5) |

43.7 (1,110) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.3 | 11.2 | 10.3 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 10.3 | 66.4 |

| Source: NOAA[150] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Big Sur is sparsely populated with about 1,000 year-round residents, according to the 2000 U.S. Census, about the same number of residents found there in 1900.[19] Big Sur residents include descendants of the original ranching families, artists and writers, service staff, along with wealthy home-owners. These wealthy homeowners, however, are usually only part-time residents of Big Sur. The mountainous terrain, environmental restrictions imposed by the Big Sur Coastal Use Plan,[111] and lack of property and the expense required to develop available land, have kept Big Sur relatively unspoiled. The economy is almost completely based on service industries associated with tourism.

Census data

The United States does not define a census-designated place called Big Sur, but it does define a Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA), 93920. Because Big Sur is contained roughly within this Zip Code Tabulation Area, it is possible to obtain Census data from the United States 2000 Census for the area even though data for "Big Sur" is unavailable.[151]

According to the United States 2000 Census, there were 996 people, 884 households, and 666 housing units in the 93920 ZCTA. The racial makeup of this area was 87.6% White, 1.1% African American, 1.3% Native American, 2.4% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 5.5% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 9.6% of the population.[151]

In the 93920 ZCTA, the population age was widely distributed, with 20.2% under the age of 20, 4.5% from 20 to 24, 26.9% from 25 to 44, 37.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43.2 years.[151]

The median income in 2000 for a household in 93920 ZCTA was $41,304, and the median income for a family was $65,083.[151] These estimates exclude the sizeable number of residents who live in Palo Colorado Canyon, who are included in the Carmel Valley Zip Code Tabulation Area.[152] As of 2004, there were about 300 households in the Palo Colorado Canyon area.[153]

Settlements

.jpg)

Existing settlements in the Big Sur region, between the Carmel River and the San Carpoforo Creek, include:

- Carmel Highlands

- Gorda

- Lucia

- Notleys Landing

- Plaskett

- Posts

- Ragged Point

- Slates Hot Springs

State and federal lands

State parks

From north to south, the following state parks are in use.

- Carmel River State Beach

- Point Lobos State Natural Reserve

- Garrapata State Park

- Point Sur State Historic Park

- Andrew Molera State Park

- Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park

- Julia Pfeiffer Burns State Park

- John Little State Natural Reserve

- Limekiln State Park

Federal wilderness

Points of interest

- Bixby Creek Bridge

- Point Sur Lighthouse

- McWay Falls

- Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve

- Sand Dollar Beach

- Jade Cove

Government

At the county level, Big Sur is represented on the Monterey County Board of Supervisors by Supervisor Dave Potter.[154]

In the California State Assembly, Big Sur is in the 17th Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Monning, and in the 30th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Anna Caballero.[155]

In the United States House of Representatives, Big Sur is in California's 20th congressional district, represented by Democrat Sam Farr.[156]

Notable current and former residents

A number of famous people have called Big Sur home, including diplomats Nicholas Roosevelt, famed architects Nathaniel Owings and Phillip Johnson, Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling, show business celebrities Kim Novak and Allen Funt, and business executives Ted Turner and David Packard.[157]

Others include:

- Ansel Adams photographer/musician

- Morley Baer photographer

- Kaffe Fassett textile artist

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti, author

- Al Jardine, musician

- John Nesbitt radio announcer, television producer, writer Passing Parade

- Emile Norman artist

- Carolyn Mary Kleefeld author, artist

- Henry Miller author

- Linus Pauling scientist, author, Nobel Prize winner

- Trent Reznor musician

- Johnny Rivers musician

- Hunter S. Thompson, author

- Jean Varda, author

- Cole Weston photographer

- Edward Weston photographer

- Vilmos Zsigmond cinematographer

In popular culture

Big Sur is mentioned by the Red Hot Chili Peppers in their 2000 single "Road Trippin'." The song describes a road trip in which lead singer Anthony Kiedis, guitarist John Frusciante, and bassist Flea surfed at Big Sur following John's return to the band.

The Beach Boys's single "California Saga: California" on the band's 1973 album Holland is a nostalgic depiction of the rugged wilderness in the area and the culture of its inhabitants. The first part describes the region's environment, the second part is an adaption of the Robinson Jeffers poem The Beaks of Eagles, and the third part references local literary and musical figures.[158]

Among other notable mentions of Big Sur in music are Charles Lloyd' album Notes from Big Sur, Buckethead's song "Big Sur Moon" on the album Colma, the song "Big Sur" by Irish indie band The Thrills from their album So Much for the City, Jason Aldean's "Texas Was You," and Siskiyou's song "Big Sur," the 7-minute-long penultimate track from their debut self-titled album. Death Cab for Cutie's song "Bixby Canyon Bridge" is about a bridge (Bixby Creek Bridge) near the cabin in which Jack Kerouac stayed. Singer Johnny Rivers' hit song "Going Back to Big Sur" in 1969, on his Realization album, was typical of the songs of that era praising the unique qualities of Big Sur.

References

- ↑ Conaway, James (May 2009). "Big Sur's California Dreamin'". Smithsonian. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Marvinney, Craig A. (1984). "Land Use Policy Along the Big Sur Coast of California; What Role for the Federal Government?". UCLA Journal of Environmental Law & Policy. Regents of the University of California. Accessed 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Lindsay, Robert (January 28, 1986). "Plan for Big Sur Severely Restricts Development". New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Big times in Big Sur". Washington Times. July 7, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Henson, Paul; Donald J. Usner (1993). "The Natural History of Big Sur" (PDF). University Of California Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Letter from Karin Strasser Kauffman". The Big Sur Local Coastal Program Defense Committee. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Barnett, Mary (March 1981). "Big Sur LCP Adopted by County Planners" (PDF). Big Sur Gazette. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2014.

- 1 2 Diehl, Martha V. (May 15, 2006). "Land Use in Big Sur: In Search of Sustainable Balance between Community Needs and Resource Protection" (PDF). California State University Monterey Bay. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 walton, John (2007). "The Land of Big Sur Conservation on the California Coast" (PDF). California History. 85 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Woolfenden, John (1981). Big Sur: A Battle for the Wilderness 1869-1981. Pacific Grove, California: The Boxwood Press. p. 72.

- ↑ "Driving California's Big Sur". Lonely Planet. July 15, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "The Big Sur Community". Big Sur International Marathon. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Station and Equipment". Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Big Sur: Images of America, Jeff Norman, Big Sur Historical Society, Arcadia Publishing (2004), 128 pages, ISBN 0-7385-2913-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 JRP Historical Consulting Services (November 2001). "Big Sur Highway Management Plan" (PDF). Corridor Intrinsic Qualities Inventory Historic Qualities Summary Report. CalTrans. p. 38. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

- ↑ "The Big Sur - Last Frontier of United States" (11). Reading, Pennsylvania: Reading Eagle. February 7, 1960. p. 75. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ Bolton, Herbert E. (1927). Fray Juan Crespi: Missionary Explorer on the Pacific Coast, 1769-1774. HathiTrust Digital Library. (This book also contains a translation of Crespi's diary from the Fages 1772 expedition.)

- ↑ "History of Big Sur California". bigsurcalifornia.org. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- 1 2 3 Road Trip USA: Cross-Country Adventures on America's Two-Lane Highways Jamie Jensen

- ↑ Lindsey, Robert (January 28, 1982). "Plan For Big Sur Severely Restricts Development". New York Times.

- ↑ Thomas, Amelia. "Driving California's Big Sur". Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ "Top 5 Best Driving Roads in America". Buick. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ "Trip Advisor Crowns Monterey County With Three 2008 Travelers' Choice Destination Awards". Monterey County Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008.

- 1 2 Gold, Herbert (January 29, 1984). "To (And In) Big Sur, The Way is Clear". New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Big Sur Land Use Plan".

- ↑ Knickerbocker, Brad (July 14, 1978). "Big Sur: Love it or Leave it" (PDF). Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ Road trip on the Pacific Coast Highway

- ↑ Vincent, David (June 20, 2009). "To Sur, With Love". Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Strong, Kathy (December 15, 2015). "Wild curves, waves — and food in Big Sur". Desert Sun.

- ↑ "California - Monterey County - Historic Districts". National Register of Historical Places. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Deetjen's Big Sur Inn Rooms and Rates". www.deetjens.com. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "What is the average price of a room at Post Ranch Inn? - Monterey, Carmel & Big Sur Hotels - Forbes Travel Guide". Forbes Travel Guide. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ Big Sur Chamber of Commerce

- ↑ Lewis, Alan. "Nepenthe Restaurant, Big Sur, California". Nepenthe Big Sur. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "Fernwood Resort Bar & Grill Big Sur, California". Fernwood Big Sur. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ↑ "Big Sur Deli: Menu". bigsurdeli.com. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- 1 2 Parachini, Allan (April 20, 1986). "Big Sur Development: Who's in Charge Here? Sen. Wilson's Bill, U.S. Supreme Court May Upset State Panel's Land-Use Plan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Heinrich, Ben. "The Development Of Big Sur". The Heinrich Team. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ↑ "Big Sur Lodging Guide, Big Sur California". bigsurcalifornia.org. Retrieved 2016-09-06.

- ↑ "The Most Expensive Gas In America?". ABC News. March 26, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ↑ McKinley, Jesse (March 12, 2008). "Most Stunning View in Town Is the One at the Pump". The New York Times.

- 1 2 Nedeff, Nicole (December 1, 2004). "Garrapata Creek Watershed Assessment and Restoration Plan Riparian Element" (PDF). Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Why Defense". The Big Sur Local Coastal Program Defense Committee. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Big Sur Coast Land Use Plan" (PDF). Monterey County Planning Department. February 11, 1981. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Short Term Rental Ordinances (Coastal - REF130043 & Inland - REF100042)". Monterey County Resource Management Agency Planning. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Susan Craig - Correspondance". Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Fay, J. Michael (September 30, 2008). "Redwood Transect-Big Sur Redwoods 2.0". Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ↑ Cross, Robert (2010). Big Sur tales. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1456711498.

- 1 2 "Pico Blanco Scout Reservation" (PDF). Monterey Bay Area Council, Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ "Camp Pico Blanco Fish Ladder and Dam Retrofit". WaterWays Consulting. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Becker, Gordon S.; Reining, Isabelle J. (October 2008). "Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Resources South of the Golden Gate, California". Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration.

- ↑ "North-Central California Coast Recovery Domain 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation of Central California Coastal Steelhead DPS Northern California Steelhead DPS" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ "Ventana Wild Rivers Campaign Little Sur River". Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2008). Stromberg, Nicklas, ed. "California Giant Salamander: Dicamptodon ensatus". GlobalTwitcher.

- ↑ "Species factsheet: California Condor Gymnogyps californianus". BirdLife International. 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Condors End 100-Year Absence In Norcal Woods". Ventana Wildlife Society. 2006-03-29. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Rogers, Paul (October 11, 2016). "California condors: Chick born in wild flies from nest at Pinnacles National Park for first time in a century". The Mercury News. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ "Fresh Hope For Condors". Sky News. March 30, 2006. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- ↑ Thornton, Stuart (May 25, 2006). "Condors make a meal of a beached gray whale". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ Wright, Tommy (September 1, 2016). "Soberanes Fire could be beneficial for condors". Monterey Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ "California Condor Recovery Program (monthly status report)" (PDF). National Park Service. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Concepts of Biology: Introduction to the Chaparral". Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Vale, Thomas R., ed. (2002). Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. ISBN 9781559638890.

- ↑ Earle, CJ (2011). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. Olympia, Washington: self-published. Retrieved 2011-08-13.

- ↑ Ramage, B.S.; OʼHara, K.L.; Caldwell, B.T. (2010). "The role of fire in the competitive dynamics of coast redwood forests". Ecosphere. 1 (6): article 20. doi:10.1890/ES10-00134.1.

- ↑ Rogers, David (2002). "History of the Monterey Ranger District Part I". Ventana Wilderness Association. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Rogers, David. "The Big Sur Fire of 1906". Double Cone Quarterly. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ↑ Rowntree, Lester (October 1, 2009). "Forged by Fire Lightning and Landscape at Big Sur". Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ↑ Fehd, Amanda (July 3, 2008). "Big Sur evacuated as massive wildfire spreads". SignOnSanDiego.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ "Threat to Big Sur eases by Steve Rubenstein, John Coté, and Jill Tucker". San Francisco Chronicle. July 9, 2008.

- ↑ Uncredited (July 19, 2008). "Progress Reported in California Fires". New York Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ Cathcart, Rebecca (August 1, 2008). "Fire Damage Takes a Toll on the Economy in Big Sur". New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ↑ Murphy, Mike (August 1, 2016). "Wildfire cripples tourism in California's scenic Big Sur". MarketWatch. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Cultural History ]".

- ↑ Analise, Elliott (2005). Hiking & Backpacking Big Sur. Berkeley, California: Wilderness Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Pavlik, Robert C. (November 1996). "Historic Resource Evaluation Report on the Rock Retaining Walls, Parapets, Culvert Headwalls and Drinking Fountains along the Carmel to San Simeon Highway." (PDF). California Department of Transportation. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- 1 2 Meighan, Clement W. (1952). "Excavation of Isabella Meadows Cave, Monterey County California" (PDF). Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Breschini, Gary S.; Trudy Haversat. "A Brief Overview of the Esselen Indians of Monterey County". Montery County Historical Society. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Santa Lucia Range ecological subregion information". Archived from the original on March 15, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2014.