Black Patch Tobacco Wars

The Black Patch Tobacco Wars were a period of violence in the dark tobacco region of the U.S. states of Kentucky and Tennessee at the turn of the 20th century circa 1904-1909.

The so-called "Black Patch" consists of about 30 counties in southwestern Kentucky and northwestern Tennessee; during that period this area was the leading worldwide supplier of Dark Fired Tobacco. Dark Fired Tobacco is so named due to the wood smoke and fire curing process which it undergoes after harvest. This type of tobacco is used primarily in snuff, chewing and pipe tobacco.

The primary antagonists were the American Tobacco Company (ATC) (owned by James B. Duke), historically one of the largest U.S. industrial monopolies, and the Dark Tobacco District Planters' Protective Association of Kentucky and Tennessee (PPA), an association of farmers formed September 24, 1904 in protest of the monopoly ATC practice of paying deflated prices for their product.

The initial idea of the PPA was to "pool"[1] and withhold their tobacco until the ATC agreed to pay higher prices. When this plan was unsuccessful, many farmers resorted to violence and vigilante practices, which resulted in the destruction of crops, machinery, livestock, tobacco warehouses and even the capture of whole towns by the group known as the Silent Brigade or Night Riders.

The players

The American Tobacco Company

James Buchanan "Buck" Duke of North Carolina was an ambitious businessman and farmer who learned quickly the profit in tobacco was in the buying and selling, not producing it.[2] In 1879, the W. Duke Sons and Company was established as a tobacco manufacturer and began producing cigarettes. Two years later, the commercial cigarette rolling machine was invented by James Bonsack. Duke quickly rented two of these machines; this allowed the company to produce 400 cigarettes per minute. In 1884 he struck a deal with its inventor to use his machines, exclusively, for all the cigarettes the company manufactured, in exchange for lower royalties. This not only lowered his manufacturing cost, it allowed him to cut his retail prices so low that his competitors couldn't compete. By 1890 Duke was able to compel his major competitors to consolidate with him as the American Tobacco Company (ATC).

By 1900 the ATC had a stranglehold on the American market and had made inroads into foreign markets, impacting the majority of the world's tobacco sales either directly or through foreign partnerships. Duke used this power to reduce his tobacco-buying price by eliminating the competitive bidding process. This brought many farmers to the brink of financial ruin or facilitated the complete loss of their farms, as they found it cost more to plant their crop than they gained at its harvest.

The ATC's fixed-price purchasing policy, combined with a new Federal tax on tobacco, placed tobacco producers into an unwinnable situation.

The Dark Tobacco District Planters' Protective Association of Kentucky and Tennessee

In 1904, Felix Ewing, a wealthy tobacco grower and owner of Glenraven Plantation near the Kentucky stateline in Adams, Tennessee proposed a way for the Black Patch growers to regain control of their sale prices. Glenraven Plantation, set up like a small village, included its own church, stores and post office and its citizens were tenant farmers and sharecroppers. Because of the decline in sale price of their product, they were defecting to find better paying opportunities in the cotton industry.[3]

During the summer of 1904 Ewing spread his idea throughout the region and on September 24, 1904 hosted a meeting in Guthrie, Kentucky, attended by some 5,000 locals. He presented a plan to get every farmer throughout the area to join a protective association whose purpose was withholding their tobacco from the Trust until buyers paid their asking price.[2]

The group moved to form the new organization, the "Dark Tobacco District Planters' Protective Association of Kentucky and Tennessee", referred to as the PPA. Officers were appointed, and a charter drawn up and approved. One article of that charter laid the groundwork for the years of unrest and violence that were to follow. It called upon each member to use his influence and strong endeavor with those tobacco planters who are not members of the Association to become members.[2]

The PPA gained instant popularity throughout the region, among the farmers and businessmen. For those who were indifferent about the Association, a boycott of their businesses was generally enough to convince them to join.

The number of members soared as farmers anticipated an immediate resolution to their problem, and included judges, prosecutors and law enforcement officials. However, some farmers simply refused to join, and when the Trust fought back by offering exceptionally higher prices for tobacco sold by non-members, the number of holdouts increased. Association members referred to these hold-outs as hillbillies.

The Association inadvertently had a flip side. The attitude, if you aren't for it you're against it, caused neighbors who had been friends and worked closely together, to be viewed as enemies. This would only get worse as PPA members turned to violence to "persuade" former friends to join.

Conditions for the growers did not improve by 1905, causing dissension among the members who had expected an immediate turnaround. What had started as an idea for a peaceful resolution turned ugly.

The Silent Brigade and The Night Riders

Ewing fell ill and became less of a regular presence, opening the door to a more radical approach to handling the farmers' problems. Dr. David Amoss, a farmer and country doctor from Cobb, Kentucky located in Caldwell County, came to a position of notoriety, within the Association, at the point when the members' frustration was turning to action.

Possum Hunters

"In October 1905 thirty-two members of the Robertson County Branch of the PPA met at the Stainback schoolhouse in the northern part of the county and adopted the "Resolutions of the committee of the Possum Hunters Organization." The possum hunters outlined their grievances against the Trust and the hillbillies and stated their intention to visit Trust tobacco buyers and hillbillies in groups of no less than five and no more than two thousand and use "peaceful" methods to convince buyers and non-poolers to adhere to the PPA."[4]

The idea caught on quickly as Possum Hunter groups began springing up throughout the region. As outlined, they simply paid visits to non-PPA members, delivering stern lectures on the advisability of joining the cause. Gradually, however, their activities grew more violent.[5]

Rise of the Night Riders: The Black Patch turns violent

Amoss had been a cadet and drillmaster at Major Ferrell's Military School in Hopkinsville, KY, and he used his military background to begin training his groups in a military fashion.

His men were conducting nocturnal mounted raids, wearing masks, hoods and robes, and riding in well-organized columns of twos. No longer content with mere lectures, they began administering beatings and whippings to noncompliant hillbillies, officials and Trust employees. They burned hillbillies' barns and destroyed their tobacco fields and plant beds by scraping, salting, or choking the young plants with grass seed.[6]

Amoss was specific regarding the mandate: Burn or otherwise destroy the property of growers and whip them and other persons who refuse to cooperate with them in their fight against the Trust.

When on a mission, they muffled their mounts' hooves, and rode silently, carrying torches and lanterns. As a result, they began referring to themselves the Silent Brigade, and by mid 1906, numbered an estimated 10,000 members.[6]

Amoss had a second even darker plan for the Silent Brigade. While it was perfectly fine to intimidate the noncompliant growers, the impact would be greater if they also destroyed the warehouses in which the Trust stored its tobacco.

The Silent Brigade executed its first attack at Trenton, Kentucky, burning the tobacco warehouse and factory of an independent dealer who had bought non-association tobacco. They then dynamited a warehouse in Elkton, Kentucky.[7]

On December 1, 1906 the Silent Brigade (now known in the press as The Night Riders) raided Princeton, Kentucky and torched the world's largest tobacco factories.

Raid on Princeton, Kentucky

According to local accounts, small groups of Night Riders drifted into town during the day and at an appointed time some raided and occupied the police station, while others simultaneously seized the telegraph and telephone offices, as well as the fire station, and shut off the city water supply.ref name="Cunningham"/> Then some 200 masked men rode down the main street of Princeton going directly to the American Tobacco Company's two large warehouses. If anyone looked out or tried to venture outside the riders would shout 'stay inside and keep the lights off', then send bullets in their direction some that shattered windows and door frames.[6]

Using dynamite, kerosene, and torches, the men lit the warehouses and their contents on fire and stood watching them burn, completely destroying both.

With three long whistle blasts the men came together, then slowly and methodically rode out of town singing "The fires shine bright on my old Kentucky home" bringing the night of terror to an end.

Raid on Hopkinsville

News of the Princeton raid spread rapidly and because of its close proximity the citizens of Hopkinsville, Kentucky sensed that their town would be next. The police, a large contingent of armed citizens and the Militia readied themselves to protect the town from the expected raid.

On January 4, 1907, Hopkinsville Mayor Charles Meacham received a telephone warning that the Riders were coming. This set the defense plan in action, the different units were alerted and took their positions for the defense of the city. The warning had been a hoax to test how prepared the city actually was.

As had been the case in Princeton, Night Riders drifted in and out of town to keep an eye on what was going on in order to properly plan the raid and be prepared to pull it off at the right time. Night after night the riders assembled ready to strike, one such night as they approached the city limits they received word the Militia was lying in wait for them and turned back.

It was a little over a year before a night finally came where vigilance was relaxed. In the early hours of December 7, 1907, the Silent Brigade struck Hopkinsville.

Having left their horses on the outskirts of town around 250 masked men marched down 9th Street to Main where they separated and carried out their orders with military precision. Several men guarded the routes into the city and other downtown streets while others took control of the police and fire departments, L&N rail depot and the telephone and telegraph offices essentially cutting off communications. Others rode up and down the streets shooting out windows whenever a light would be turned on. Several people were held hostage in a makeshift corral on Main street. Many businesses were vandalized including the newspaper office, and a buyer for a local tobacco company, Lindsey Mitchell,[8] was dragged from his home and beaten. In a few minutes the Night Riders had complete control of the city.[9]

The largest group then proceeded to first burn the Latham warehouse near the Rail Depot then the Tandy and Fairleigh warehouse a few blocks away. The fires burned out of control, igniting several residences and even the Association's warehouse. A brakeman, J.C. Felts[8] working for the railroad was shot in the back with 35 rounds of buckshot (which proved to not be fatal) as he tried to save railcars from the fire. Dr Amoss was even wounded in the head by his own men and was taken away from town early to be treated.[6]

As had occurred in Princeton, when the raid concluded the men assembled, and sang "My Old Kentucky Home" while riding out.

While the raid was taking place Major Bassett, the leader of the militia, slipped out of a rear window in his house and raised a posse of eleven men to pursue the Night Riders when they left town.[9] Because the Night Riders failed to post a rear guard, members of the posse were able to intermingle with the group. Several miles outside of town the Night Riders split up with most riding off in a different direction. The posse staying with the smaller group opened fire, killing one and injuring another.

As a result of the raid on Hopkinsville, The Kentucky Militia was ordered on active duty and Major Bassett was given command of all military operations in the area. The Militia would remain on duty from December 1907 until November 1908. There would be no raids where the soldiers were stationed.[9]

Raids on Russellville

In the early hours of January 3, 1908, while the soldiers were guarding Hopkinsville and other towns, the night riders left their mounts outside the town and marched into Russellville, Kentucky. Using similar tactics as used previously, they took over the town and dynamited two factories, one belonging to the Luckett Wake Tobacco Company and the other to the American Snuff Company.[8][10] On August 1, 1908 one hundred men believed to be Night Riders entered the jail in Russellville and demanded four black prisoners, Joseph Riley, Virgil, Robert, and Thomas Jones. The jailer complied, and what happened next is still not talked about much even today by Russellville locals.

The four men were local sharecroppers, and friends with a man named Rufus Browder, also a sharecropper for a man named James Cunningham. Cunningham and Browder had engaged in an altercation with his employer Cunningham where Cunningham hit Browder with a whip and shot him as Browder had turned to walk away. Browder then shot Cunningham in self-defense killing him. Browder was arrested and taken to another town for protection. His friends and Masonic lodge brothers Riley and the three Jones were arrested for having expressed approval of Browder's actions as well as discontentment with their employers.

It is believed the Night Riders were responsible for entering the jail, taking the four men outside, then lynching them from the same tree. One of the men had pinned to his clothing a grave warning to blacks causing trouble for whites. Due to the very offensive nature of the note I will not place its contents here.[11]

Raids in Crittenden County

On February 4, 1908, Crittenden County was raided for the first time. Night riders took over the small village of Dycusburg, Kentucky burning the tobacco warehouse and distillery of Bennett Bros.[8] During the raid they took W. B. Groves from his home and severely whipped him because he refused to join the Association. They also took out Henry Bennett and, after binding him to a tree, whipped him with the branches of a thorn tree.

During the early hours of the following Sunday February 10, the county was again visited. The farm of A. H. Cardin, a former candidate for governor of Kentucky was singled out, and a large warehouse, containing tobacco, which Cardin had bought for Buckner & Dunkerson of Louisville, and a barn containing tobacco which had been grown on the farm, was burned.[8] En route to Cardin's farm, the night riders passed through the small town of Fredonia, Kentucky in Caldwell County, which they captured and held under guard for four hours, while the main group traveled the six miles to Cardin's farm near Mexico, Kentucky, accomplished their work and returned.

The wars come to an end

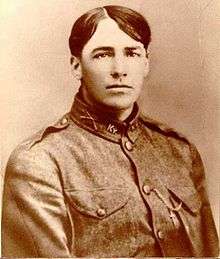

In April 1908 a Kentucky National Guard detachment commanded by Captain Newton Jasper Wilburn (then a lieutenant) led a series of raids against the Night Riders' leaders. Wilburn arrsted several Night Rider leaders, and provided protection to several key informers. He gained the help of former Night Riders, including Macon Champion, who implicated fifteen other local farmers. The arrests broke the power of the Night Riders and effectively ended the Black Patch War. Lieutenant Wilburn was rewarded with a promotion to captain. Even though most eventually escaped justice, Capt. Wilburn's actions helped bring law and order to the region.

Aftermath

By the summer of 1910, the Night Rider trouble had come to an end except for a few scattered minor episodes. The tobacco growers were receiving higher prices for their crops, and the U.S. Supreme Court rules that ATC was indeed a monopoly and must be dismantled.

As a result of his efficiency in handling the difficult situation arising from the Tobacco War, Gov. Augustus F. Wilson commissioned Major Bassett a Lt. Colonel in the Kentucky Militia. Col. Bassett was called on several times to protect witnesses during the trials of the Night Riders.

John C. Latham did not rebuild his warehouse but gave the site to the city of Hopkinsville to be used as a park. It was named Peace Park.

Many of the Night Riders escaped prosecution while others were sued in civil courts.

Dr. Amoss faced trial in the Christian County Court and in March 1911 was acquitted of all charges. He then accompanied his son, also a physician, to New York City, where he practiced until his death in 1915.

Resolution

On May 9, 1911, the United States Supreme Court ruled in United States v. American Tobacco Co. that the Duke trust, ATC, was indeed a monopoly and was in violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890.[12]

Poetry

THE OLD KNOTTY OAK

On the old Knotty Oak in North Christian

Way out on the Kirkmansville Road,

There has lately been posted a notice,

To all farmers, the bad and the good.

Its just a "guilt" edged invitation

Placed there by a Night Rider brave (?)

"Better join the 'Sociation,

If you plant beds and barns you would save."

It was stylishly dressed up in canvas,

And written by type-writer's hand,

It was worded in terms so expressive,

That any one might understand.

The farmers were warned to come over,

that they were in danger outside,

All tobacco must be in the union,

And the signature this "Men who ride."

Now, Old Knotty has long been a landmark,

Not noted for beauty 'tis true,

But a study and silent old fellow

And of secrets he's heard quite a few.

Wiley words of the smooth politician,

Merry laughter of children at play.

Whispered wooing of lovers by moonlight,

All of these he has heard in his day,

The patient ox, the tired horses in summer

How they long for his shade by the road.

To them he's the feed ground, the noon hour,

and rest from the weary road.

Old has held all the sale bills;

He's proud of the nails in his side.

But his head hangs in humiliation

At the threat of the bad "Men who ride."

However he's keeping the secret,

but of course he would know just at sight

The face of the man who disgraced him,

by posting a threat in the night

The people who live near Old Knotty,

and quietly working their farms,

but they've nothing to lose by marauders,

No plant beds, tobacco or barns.

They are not opposed to the Union,

Its findings they would not revoke.

But they'd like a 'polite invitation,

Instead of a threat to the Oak.

They've read long ago, in an old book,

That in Union alone man may stand;

That a house with its members divided,

Is like the one build on the sand.

then, here's to the D.T. 'Sociation,

May its principles ever abide,

Here's to order and law in Old Christian

But contempt for the men who ride."

- -This poem was published many years ago in The Kentucky New Era.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Suzanne Marshall, "Violence in the Black Patch of Kentucky and Tennessee" (1994)

- 1 2 3 Tracey Campbell, "The Politics of Despair: Power and Resistance in the Tobacco Wars" (1993)

- ↑ Christopher Waldrep, "Night Riders: Defending Community in the Black Patch, 1890-1915" (1993)

- ↑ http://www.tennesseencyclopedia.net

- ↑ James O. Nall, "The Tobacco Night Riders of Kentucky and Tennessee, 1905-1909" (1939)

- 1 2 3 4 Cunningham, William. "On Bended Knees." McClanahan Publishing, 1983.

- ↑ http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread831032/pg1

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Country Gentleman Newspaper 1908 p. 252

- 1 2 3 http://www.westernkyhistory.org/christian/night.html

- ↑ Griffin, Mark. Stand There and Tremble: When the Night Riders Came to Russellville . Pumpkin Bomb Press (2008)

- ↑ http://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-lynching6.html

- ↑ United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106 (1911)

- ↑ The Kentucky New Era

References

- Adams, James Truslow. Dictionary of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940

- Cunningham, William. "On Bended Knees." McClanahan Publishing, 1983

- "Secretary's Books to be Turned over by Night Rider Leader," Hopkinsville Kentuckian, 18 April 1908

- Vivian, H.A. "How Crime Is Breeding Crime in Kentucky." New York Times, 26 July 1908

- Griffin, Mark. Stand There and Tremble: When the Night Riders Came to Russellville." Pumpkin Bomb Press, 2008

- Gregory, Rick "www.tennesseencyclopedia.net", 2010Reading

- Tracey Campbell, "The Politics of Despair: Power and Resistance in the Tobacco Wars" (1993)

- Suzanne Marshall, "Violence in the Black Patch of Kentucky and Tennessee" (1994)

- James O. Nall, "The Tobacco Night Riders of Kentucky and Tennessee, 1905-1909" (1939)

- Christopher Waldrep, "Night Riders: Defending Community in the Black Patch, 1890-1915" (1993)

External links

- http://spider.georgetowncollege.edu/htallant/border/bs9/gregory.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20041124160752/http://www.nkyviews.com:80/Other/text_night_rider%20movement.htm

- http://www.westernkyhistory.org/christian/night.html

- Black Patch War, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture