Blood Road

Coordinates: 67°06′N 15°29′E / 67.100°N 15.483°E

The Blood Road (Norwegian: Blodveien) is a route northeast of Rognan in the municipality of Saltdal in Nordland county, Norway that was built by prisoners of war during the Second World War.[1][2][3] The route was a new section of Norwegian National Road 50 between Rognan and Langset on the east side of Saltdal Fjord (Saltdalsfjorden), where there was a ferry service before the war. The specific incident that gave the road its name was a cross of blood that was painted on a rock cutting in June 1943. The blood came from a prisoner of war that was shot along the route, and the cross was painted by his brother.[2][4]:16[5]

The prisoners of war lived in a primitive camp in the village of Botn, just 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) outside Rognan.[5] The prisoners of war had very small daily rations, long working hours, poor clothing for winter use, primitive barracks, and miserable sanitation, and they were treated cruelly. The Botn camp was first led by the SS, and under their direction mass executions were also carried out.

When the Wehrmacht took over management of the Botn camp in October 1943, the conditions gradually improved. The conditions further improved when the Red Cross learned of the camps and several inspections were conducted.

The Botn camp was one of five original prisoner-of-war camps in Northern Norway. The camp held prisoners from Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and Poland.[2] The youngest prisoners of war were barely 12 years old. The conditions at all five camps were poor with high mortality. The number of prisoners in the Botn camp can only be estimated from testimonies of survivors. Almost 900 prisoners in total arrived at the camp; of these, about half died through execution, punishment, malnutrition, and exhaustion.

By the war's end there were around 7,500 prisoners of war in Saltdal, but the number is uncertain. There were up to 18 camps from Mount Salt (Saltfjellet) and north to Saltdal Fjord, but the treatment that prisoners received in these camps was considerably better. In the trials held after the war, the camps were referred to as extermination camps. It shocked the Norwegian authorities that the Norwegian youths as young as 16 had served as guards in the camp. The youths were members of the Hirdvaktbataljon (Guard Battalion of the Hird) set up under the NS Ungdomsfylking (the Nasjonal Samling youth organization), and they treated the prisoners of war cruelly. In the postwar trials several Norwegian guards received prison sentences, and some of the German SS officers were sentenced to death by firing squad.

Background

Building the road and rail connections

During the occupation of Norway in the Second World War, the German forces had enormous transport needs, particularly in Northern Norway, where, among other things, they needed to bring supplies to the north front, transport ore from LKAB via Narvik, nickel from Finland, and personnel and material throughout the entire region. Transport by ship along the Norwegian coast was hazardous due to allied bombing. The road network was poor and insufficiently developed. The Nordland Line went no further north than Mosjøen, and on the trunk roads there were many ferry crossings. Railroad development was centrally seen as the only solution to obtain satisfactory transport. Adolf Hitler ordered the rapid development of the Polar Line to Kirkenes; the German commander in Norway, Generaloberst Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, demanded 145,000 prisoners of war to carry out development of the railroad to Kirkenes within four years.

The very comprehensive plan was set aside, and in the first round 30,000 POWs were brought in to carry out railroad construction from Mosjoen to Tysfjord.[4]:3 The Todt Organization was responsible for all road development in the occupied countries, and a sub-unit named Einsatzgruppe Wiking (the Viking Task Force) took responsibility for building the railroad between Mo i Rana and Fauske.[4]:5

By the war's end, the Wehrmacht had used 78,200 POWs as slave labor in Norway. Of these, about 1,600 were Poles, 1,600 were Yugoslavs, and the majority, around 75,000, were Soviet citizens.[6]

Five main camps in Northern Norway

The prisoners of war were sent through central Europe to Szczecin on the Baltic Sea. On the way to Norway, they were quartered at various German camps.[7]:44 The transport from Szczecin was by ship to either Bergen or Trondheim, and then further north to the five main camps. The northernmost one was located in Karasjok, the camp at Beisfjord was the largest, the Botn camp was located in Saltdal, and in the southern part of Northern Norway were the Osen and Korgen camps.[8]:37 These first five camps are also known as the "Serbian camps" (Norwegian: serberleirene). However, there were many more small camps throughout Northern Norway. Between Korgen and Narvik alone there were up to 50 camps with around 30,000 prisoners.[4]:8

It appears certain that here one is dealing with pure annihilation camps and that the purpose was to systematically exterminate all of the prisoners. In the face of starvation, abuse, and hard work, the prisoners' health systematically failed, after which they either died or were euthanized as useless.

Norsk Retstidende, 1947, page 376

In the summer of 1942, about 2,500 Yugoslav prisoners of war arrived at these five camps, and by the next summer only about 750 were still alive. The differences between the camps are apparent from the fact that that in the camp at Bakken further up in Saltdal no prisoners died over the span of three years.[4]:7

The conditions in many of the camps were cruel. Responsibility in the camps was split up systematically, so that the individual German officer with responsibility in each camp could with a certain kind of justification declare himself not liable for the misery. The personal character of the camp commandant was decisive for the conditions in each camp.[4]:6

Norwegian National Road 50 between Rognan and Fauske

Road construction was to take place simultaneously with railroad construction. Norwegian National Road 50 over Mount Salt (today E6) was opened in 1937, but it was a low-quality road. From Rognan to Langset, a few kilometers north in Saltdal Fjord, there was a ferry. Further north in Salten there were also many longer ferry connections. In December 1941, the Germans demanded forced road construction and offered prisoners to the Directorate of Public Roads to carry out the work. It was agreed to prioritize the three road systems in Korgen, in Botn in Saltdal, and around the Beis Fjord in Ofoten.

The new road over Mount Korg (Norwegian: Korgfjellet) in the municipality of Korgen was intended to replace another ferry connection along Norwegian National Road 50 between Elsfjord and Hemnesberget. On June 23, 1942, Yugoslav prisoners of war were brought to two camps: to Fagerlimoen (in Korgen) and to Osen (in Knutlia). The camps were active until the summer of 1943. A temporary bridge was set up over Beis Fjord in Ofoten in July 1943 and a ferry connection was set up between Fagernes and Ankenes. This was replaced by the Beisfjord Bridge in 1959. The Beisfjord camp was located in Beisfjord, 13 kilometers (8.1 mi) south of Narvik, and was active from June 1942 until the end of the war.

The Blood Road was a road section northeast of Rognan in the municipality of Saltdal. The road was a new section of Norwegian National Road 50 between Rognan and Langset on the east side of Saltdal Fjord, where there was a ferry connection before the war.[6]:46 The Blood Road itself now corresponds to a section of today's European route E6 between Saltnes and Saksenvik.[4]:24 The prisoners that built the road belonged to the Botn camp.

The prisoners of war were generally treated poorly during the construction. They received small portions of simple food, their clothing was not suitable for winter use, and the hygiene conditions were extremely deficient with much lice infestation.[4]:4

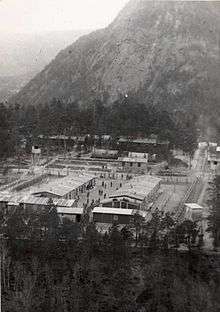

The Botn camp

The largest and best-known camp in Saltdal was in Botn near Saltdal Fjord, about 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) from Rognan. The camp was set back from the other buildings in Botn, but was still close to the work and the fjord. Around Botn there are high mountains, and the areas to the east are bare deserted mountainous terrain. Before the Blood Road was built, the little village had no road connection.

The prisoners carried out roadwork on the stretch from Rognan to Langset. Personnel from the Norwegian Public Roads Administration led the efforts technically and served as blasting foremen and facility managers.[8]:40

Background of the prisoners of war

The prisoners of way that were used in Saltdal came from Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and some were also from Poland.[4]:7

The majority of the prisoners from Yugoslavia were political prisoners, but the criminologist Nils Christie explains that their backgrounds varied, and so it is difficult to fully characterize them. Christie also offers some hypotheses for why it is probable that they were politically active.[7]:44 A portion of them were both political prisoners and Partisans, and they came from all walks of life and of all ages; the youngest were only 13 to 14 years old. The majority were Serbs, but some were also Croats.[8]:36

The labor camps in Norway and in other areas conquered by the Germans were often as bad as the "Nacht und Nebel" camps, where political prisoners in particular would "disappear." Resistance movements arose in countries occupied by Nazi Germany. Executions of captured resistance member were counterproductive because they hardened public opinion. The "Nacht und Nebel" camps would keep the prisoners' relatives and other people unaware of their fate. This system was used against resistance members both in Germany and in occupied areas. In addition, the camps constituted an important economic base for the SS-dominated state. The expenses for labor were very small and the labor supply was almost unlimited.[7]:16[9]:27

Arrival at the camp

The Botn camp was active from July 1942 to June 1944. The camp was built by the Public Roads Administration after it had been ordered to build barracks at the beginning of June 1942. The camp was fenced by two barbed-wire fences, which were about 2 meters (6 ft 7 in) high and had a 0.5-meter (1 ft 8 in) interval between them. There were three guards at the camp. Two barracks were built with simple boarded exteriors and floors without a foundation. The barracks contains five-tiered bunk beds. Outside the camp was the barracks for the guard crew. When the guard was installed on June 20 was the building not yet finished. The commandant of the camp was Hauptsturmführer Franz Kiefer, and he was in charge of six officers and two NCOs, all members of the SS. In addition, there were ten to twelve military police and another NCO. The commandant of the Osen camp, Sturmbannführer Dolph, was also given oversight over the Botn camp and Korgen camp.[8]:39

The first prisoners at the Botn camp were 472 Yugoslavs[7]:87[10] that arrived by ship on July 25, 1942. They had been brought by ship from Szczecin to Bergen on June 2. Twenty-eight of the prisoners were already shot upon arrival in Bergen. From Bergen, they were sent by ship to Botn, and 400 prisoners were sent further on to Karasjok. The Furumo farm was located about 150 meters (490 ft) from the camp, and those that lived there said that the prisoners were marched from the sea up to the camp in smaller groups, while the guards shouted at and struck them, causing many to fall over.[8]:39

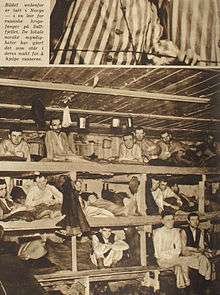

Malnutrition and pecking order

The two camps in Botn were so poorly built that the snow made its way into the prisoners' beds. The daily rations were very small, and a former prisoner described the food supplies as follows: Typically four or five men shared one loaf of bread, 50 men shared .5 kilograms (1.1 lb) of margarine, and 100 men shared 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of sausages. Each man received .5 liters (17 U.S. fl oz) of soup a day.[7]:55 The labor shifts were 14 hours long.[9]:31 Sanitation was extremely inadequate; the prisoners fetched washing and drinking water from open ditches in the camp. Outflow from the toilets often entered the channels.[4]:11

Disagreements between the Croats and Serbs were exploited by the SS guards.[Note 1] A few selected Croats received more privileged positions as kapos. The kapo system was common in Nazi concentration camps.[8]:41 The kapos received more food than they could manage to eat themselves. As a result, food barter became established, in which those with more sold their soup ration and received a half ration of bread from those that had too little. A former prisoner commented in broken Norwegian on the difference between food intake by kapos and the rest of the prisoners of war: "Among these, there were several who were so fat that they weighed over 100 kilograms (220 lb), whereas the majority were under 50 kilograms (110 lb)."[7]:55

Norwegian guards from the Hirdvaktbataljon

Regarding the guard battalion, I would like to ask you as soon as possible to withdraw it, and to send them to the Legion. Because the service these boys are performing is the most horrible I've ever heard of, since they are simply performing what was called "knacker service" in the Thirty Years' War for the Germans.

I have constantly heard rumors about what they're doing up there, and the other day I received confirmation from a man who came from there on leave because he came into my office and said "Heil og sæl, I am a trained killer." He told me that the Serbs they are guarding up there were sentenced to death in Serbia, but for one reason or another were brought up to Finnmark, and from there they will not escape alive; and it is these young Hird members' despairing duty to finish off each of these prisoners. From what my informant said, and from what I have also heard from others, the treatment of these men is inhuman. He claimed that in the time he has been there they have had to kill about seven hundred by shooting or hanging. That the Fører's young idealistic political soldiers should have to perform this kind of service is impossible and must be completely rejected.[7]:86–87

Excerpt from a letter from Hird leader Oliver Møystad to Vidkun Quisling

On August 1, 1942 about 30 Norwegian guards arrived at the camp.[8]:39 The were from the Hirdvaktbataljon (the Guard Battalion of the Hird) set up under the NS Ungdomsfylking (the Nasjonal Samling youth organization) in order to protect businesses from sabotage. The members of the Hirdvaktbataljon were as young as 16[9]:30 and were therefore (or for other reasons) not accepted for service at the front.[4]:8 They were only responsible for preventing escapes and had no responsibility for managing the labor. They had "shoot-to-kill" orders in the event of an escape. They were not formally allowed to punish prisoners, but this was not adhered to. The guard crews had rifles with bayonets, and some had automatic firearms.[8]:39

The young men in the Hirdvaktbataljon mistreated the prisoners by hitting and kicking them, throwing stones, striking them with their rifle butts, and stabbing them with bayonets. The younger the guards were, the more brutally they behaved. After the labor shifts, the guards would report poor performance to the camp management. Those accused of lack of effort were punished with 25 strokes of a cane, sometimes up to 50. The prisoners that were beaten frequently rarely lived long.[8]:41

A man living near the Botn camp stated: "I remember that among the Norwegian guards there was a very good man, who helped the prisoners with news and food, and who did not force them to work. But the Germans found out, and he suddenly vanished."[9]:96

After the war, it was also ascertained that the young men's behavior in the camp had also shocked the highest levels of Nasjonal Samling. In a private letter (see excerpt at right), Vidkun Quisling was urged to transfer the youths away from this service.[7]:86–87

SS Hauptsturmführer Franz Kiefer

SS Hauptsturmführer Franz Kiefer, who was the commandant at the Botn camp, was an exceptionally brutal man according to all witnesses.[8]:40 A young man from the Hirdvaktbataljon stated in an interview with Christie: "The Germans up there were insane. Kiefer was a devil like no other. He put his fist up in our faces when we arrived. We had to obey orders, otherwise we would be hanged immediately. Fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds lived only as long as they thought things were the way they should be."[7]:94–95

Another witness from the Hirdvaktbataljon stated: "We were so shocked that we didn't understand anything. It was snowing and cold, sad and rugged. Pigsties. The prisoners milled around and scowled, aware that something was amiss. The Germans behaved shockingly. The camp commander Kiefer came directly from an insane asylum in Germany. He walked around with a little whip that he used to beat us and others. I myself was struck in the face by him. When he was drunk he was completely out of control. 'Why didn't you take off?' people asked afterwards. I didn't know where I was, only the general direction, and around us there were snow, ice, and mountains everywhere." Christie notes that Kiefer certainly did not come from an insane asylum, but it is interesting as a characterization.[7]:94–95

Kiefer had a hammer forged with a spike on it that he used to mistreat the prisoners.[8]:40 A witness stated that he would swing his short hammer around furiously.[9]:201

Norwegian guards from the SS-Vaktbataljon

After four to five months, the first Norwegian guard crew was relieved by 180 men from the SS-Vaktbataljon (SS Guard Battalion).[4]:8 Many of the SS-Vaktbataljon guards were as brutal as those from the Hirdvaktbataljon, yet there were now a greater number that treated prisoners in a fairly orderly manner.[8]:41

Escape attempts

The first escape attempt from the camp occurred on December 14, 1942 and was carried out by Tihomir Pantović (a.k.a. "Yellow").[9]:96 The escape was something that the prisoners had agreed to among themselves. The plan was for the escapee to make his way to Sweden and tell about the conditions so that the outside world would become aware of what was going on. The prisoner that escaped was intercepted by Norwegian guards; when he understood that the attempt was unsuccessful he tried desperately to cut his throat with a lens from his glasses.[9]:96 The two Norwegian guards mistreated him so brutally that they kicked out one of his eyes and broke an arm. He was brought back to the camp, where he was kept for three days without food or water. Then he was hanged in of everyone. Those that took him down said he was bruised all over his body from punches and kicks.[8]:41

The next and last escape attempt that was made when the SS-Vaktbataljon was in charge of the camp was carried out by Svetislav Nedeljković (a.k.a. "Crazy Sveta"). This occurred on February 12, 1943 and was also unsuccessful.[9]:201 After it became known that a prisoner had escaped, extensive searched were carried out in all houses and buildings in Botn. The civilian population was interrogated and accused of hiding the fugitive.[9]:96

After the Wehrmacht took over the guard duties, Cveja Jovanović was one of the prisoners that managed to escape to Sweden. His book Flukt til friheten (Escape to Freedom) was published in Norwegian in 1985. The book describes his escape and also presents escape attempts that were made from camps in Norway. Jovanović describes in detail the risk that the escapees exposed themselves to, and what reprisals their fellow prisoners could expect.[9]:31–45 The circumstances and the dangers in escaping from the Botn camp and other camps in Salten are also thoroughly discussed.[9]:95–97,197–244

About 30 prisoners managed to escape from the camps in Saltdal in the course of three years.[4]:14 Jovanović says that 23 men escaped from the Botn camp, but he does not mention how many of those were successful.[9]:95

Mass executions

The first mass executions at the Botn camp happened in late November 1942, right after the new group with Norwegian guard crews had arrived. One of these stated what happened: "A pit was dug about 200 meters (660 ft) from the camp and the Serbian prisoners were gathered around it. The pit was 30 meters (98 ft) long, 2.5 meters (8 ft 2 in) wide, and 2 meters (6 ft 7 in) deep. Three Norwegian guards were ordered to stand watch around the group of prisoners, while the SS guards methodically shot them in the back of the head. When I came out, the Germans had already started the executions, and a boy age 13 was next in line. The boy fell down on his knees and begged for his life, but he was shot in the back of the head and fell into the grave."

The prisoners were lined up on the edge of the grave, so that they fell right into it after the shot was fired. They were shot in groups of ten, which were lined up at the edge in turns. The Norwegian guard walked to the grave and saw that several were still alive. He lost control and shouted, "But they're still alive!" He was immediately threatened with a gun by one of the SS guards and taken away from the execution site. When he talked about this at the barracks, the other guards said that he was soft.[8]:43

A prisoner that buried the bodies told the Norwegian guard that around 77 prisoners were shot, and that their age ranged from around 12 to 70 years. The corpses lay at one end of the grave. They were covered with only a thin layer of soil because more new prisoners were buried every day. The German SS guards said that the detainees were ill and were being executed to avoid infection. The Norwegian guard himself thought that the reason was that they were so starved that they had no strength to work.[8]:41

According to the Yugoslav War Crimes Commission, this execution occurred on November 26, 1942 and 73 prisoners were shot. The shooting was ordered by Untersturmführer August Riemer. The next mass execution of sick prisoners took place in January 1943. The War Crimes Commission established that 50 people were executed on this occasion and the date was determined to be 23 January. Norwegian guards were present at the event, but reportedly only German crews carried out the executions.[8]:42

The local population's connection to the camps

The local people could not fail to be aware of the conditions in the camps. Although there was no abundance of food in Norwegian homes during the war, some food was given to the prisoners. Especially those that lived near the camps gave as often as they could and recognized "kind" guards that openly permitted the prisoners to receive food. However, most often food was given by hiding it at construction sites or along the roads. Helping the prisoners could be dangerous because of reprisals. Julie Johansen lived near the Botn camp and became known as the "Yugoslavs' mother"; for her efforts she received an award from Josip Broz Tito after the war.[4]:13

In the course of three years, around 30 prisoners managed to escape from the camps in Saltdal and make their way to Sweden. The locals significantly assisted the escaped prisoners by guiding them on their way and helping with shelter, food, and equipment. Some Saltdal residents worked as border guides and the escape route usually went to the Swedish mountain farm of Mavas via Mount Salt. During the winter, this was a daunting journey and on the Swedish side many miles still remained to reach civilization. The fugitives thus also depended on help from Swedes.[4]:14–15

There was also an escape route across Mount Sulitjelma somewhat further north. Some employees of the Sulitjelma Mines that lived in the small mining community of Jakobsbakken were a known group of border guides. When they took people into the mountains and were gone a few days, this was not registered as an absence and they were paid as though they had been at work. Before coming to the mountain village of Sulitjelma, there is the village of Lakså near Upper Lake (Norwegian: Øvervatnet), where there were border guides for a slightly more northerly route. In Salten there were organized border guides, couriers, intelligence agents, and resisters making it possible for these escape routes to work.[9]:197

The most frequently used border guide in Saltdal was probably Peter Båtskar. He lived in a hut in the mountains south of Rognan, subsisted mostly on hunting and fishing, and was viewed as an odd character. He was recommended to fugitives that came from the prison camps. Among the people in Saltdal it became an adage to say: "Send him to Båtskar!" when someone was in a difficult situation.[9]:198–199

The Wehrmacht assumes guard duties

Conditions at the camp improved when the Wehrmacht took charge at Easter 1943. Of the 472 prisoners that had arrived the camp, at least 302 had died. Thus there were 170 prisoners in the camp when the Wehrmacht took over. On April 12, a new group of 300 prisoners arrived at the camp, including the then 20-year-old Ostoja Kovačević, who wrote the book En times frihet (One Hour of Freedom). The first Sunday that he was in camp, all of the new prisoners had to wash themselves outside in a small lake where ice was still floating. The German soldiers beat the prisoners and forced them into the water.[7]:44

Kovačević says that such bathing Sundays were something that happened often: "Bathing Sundays always ended with large and small tragedies. Many were so frozen stiff that they could not manage to get their clothes on, and so others had to dress them. It often happened that almost half of the prisoners had to be carried back to camp after bathing. And the Gypsies that had managed to resist both starvation and beatings were broken here. One after another, they had to be carried unconscious back to the camp, where they later died." A German non-commissioned officer had previously served as an orderly; he used to treat frostbite by chopping off frozen fingers with his bayonet.[8]:44

The blood cross along Norwegian National Road 50

On July 14, 1943 Miloš Banjac was shot by a Wehrmacht guard, and his brother drew a cross on the rock wall next to him with the dead man's blood. This event resulted in the stretch of road between Rognan and Saksenvik on the east side of Saltdal Fjord being known as the Blood Road (Norwegian: Blodveien). The cross is still marked today; see the illustration to the right.[4]:16

Notes

- ↑ There were major internal conflicts in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during World War II in which the ethnic groups opposed one another. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was one of many small countries that pledged support for the Axis, and thus was on the German side when the war began. In this state, Croats held leading political positions but soon turned against the Serbs and formed the Independent State of Croatia.

References

- ↑ Ognjenović, Gorana. 2016. The Blood Road Reassessed. In: Gorana Ognjenović & Jasna Jozelić (eds.), Revolutionary Totalitarianism, Pragmatic Socialism, Transition: Volume One, Tito's Yugoslavia, Stories Untold, pp. 205–232. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 Store norske leksikon: Blodveien.

- ↑ Ham, Anthony, Miles Roddis, & Kari Lundgren. 2008. Norway. Footscray, Victoria: Lonely Planet, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Storeng, Odd. 1997. Krigsfangenes historie – Blodveien i Saltdal. Bodø: Saltdal kommune.

- 1 2 Hunt, Vincent. 2014. Fire and Ice: The Nazis' Scorched Earth Campaign in Norway. Stroud: Spellmount.

- 1 2 Dahl, Hans Fredrik, et al. 1995. Norsk krigsleksikon 1940–45. Oslo: J.W. Cappelen, p. 229.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Christie, Nils. 1972. Fangevoktere i konsentrasjonsleire – En sosiologisk undersøkelse av norske fangevoktere i serberleirene i Nord-Norge i 1942–43. Oslo: Pax Forlag.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Parelius, Nils. 1984. Tilintetgjørelsesleirene for jugoslaviske fanger. Saltdal: Saltdal kommune. (Reprinted from Samtiden 6, 1960.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Jovanović, Cveja. 1985. Flukt til friheten: Fra nazi-dødsleire i Norge. Oslo: Gyldendal.

- ↑ Riksadvokatens meddelelsesblad 39, 1947, p. 87.