Blues, Rags and Stomps

Blues, Rags and Stomps, Op. 1, was composed by Robert Boury between 1970-1973. It consists two books, three movements each. Boury composed mostly during his graduate study at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. The first set was nicknamed “Varsity Rags”, which Eubie Blake admired and told the audience, “Now that’s ragtime”, after he heard Boury’s performance at the 1971 Toronto ragtime Festival.[1] Book I and II consist of three movements each: I. A Tristan Two-Step, II. Alice Walking, and III. The Rocket’s Red Glare. Book II: I. Eubie’s Blues, II. Stroller in Air, III. I Left My Heart. Boury comments that “A Tristan Two-step” represents his breakaway from modern music and was a way to be accepted as a tonal composer.[2]

Book I

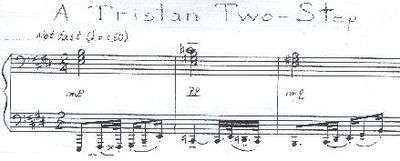

A Tristan Two-Step

Boury dedicated this movement to his colleague, Kurt Carpenter during their graduate study at the University of Michigan, and was premiered by the composer himself. The musical form is through-composed and divided into three sections: A mm. 1–33, B mm. 34–38, C mm. 39–52. Boury was influenced by the Tristan and Isolde, a story of romance and tragedy. As we know from the title of this movement, it is the style of two-step.[3] Although the 6/8 meter is commonly used for the two-step dance, Boury chose 2/4. “Compound time is just too messy for this piece. With all the development that happens, a pianist would get lost in the middle of the bar”~R. Boury.[4]

The movement starts with the first motive in the left hand, accompanied by seventh chords in the right hand. At measure 9, the second motive is presented in the right hand while the first motive continues in the left hand. There are several technical demands that need to be addressed. Due to the thick chords, they may be played as rolled chords or alternative finger number such as using a thumb to cover the bottom white key and the black key. Many chromatic scale-like runs and jump-bass accompaniment patterns in the left hand make this piece tricky to master. The pianist should practice slowly so as to avoid stumbling and only gradually increasing tempo.

Alice Walking

Between 1973–74 Boury’s interest toward film music led him to California. During his stay in California Boury was inspired by the beautiful scenic of the canyons, the ocean, and the variety of foliage. Therefore, he composed this piece, which was a reference to "Alice in Wonderland."

This short piece begins with a quiet, four measure introduction that contains many longer value notes. These long notes may reflect large scale scenery like the ocean and the canyons in California. The time signature is a common meter yet it is a complex piece to master due to the hidden melodies and syncopation. These melodies are supported by the broken accompaniment in both right and left hands. Together, the broken accompaniments and melodies might illustrate the variety of foliage that Boury was inspired to emulate from the scenery. Therefore, the pianist must capture the flowing motion of clusters of leaves by approaching lighter sonorities for the accompaniment (smaller foliage) while making melodies stand out (larger leaves and flowers).

There are some sections that may be technically demanding to some pianists. Boury frequently used many tempo indications such as accelerando and ritardando in the first half of this movement which occur very frequently. It is tricky to follow those indications yet they help to create the direction of the musical lines and colors. Other technical challenges can be the balance between the multiple lines. After this same theme comes back at measure 26, the left hand requires crossing right hand. The pianist should aim for a lightly detached motion toward the ‘bell-like’ high notes in the left hand to ensure the fantasy like character.

The Rocket’s Red Glare

Boury named this piece after the opening gesture of the American Manheim Rocket theme of the finale of Symphony No. 40 in G minor by W. A. Mozart. Although this piece was written for solo piano, there is a full orchestral quality. Like the old composers of the Mannheim school Boury used sudden crescendo in the introduction and rising arpeggiated melodic line accompanied by ostinato. Use of a wide range of keys with chromatic passages and various hairpin dynamic indications support the orchestral quality as well.

Mastering the chromatic passages is one of technical demands also the pianist must pay attention to the tenutos, accents and directions. Many swiftly rising passages are also doubled in this movement and the pianist must approach them with an ultra legato touch. Although most of the chords in this movement are easy enough to manage, some require crossing hands. In fig. 11, the left hand gets uncomfortably close to the right hand, so the pianist must use both flat hand and straight hand approach from above. Other than the introduction and the coda, Boury shifted the meter between 2/4 and 4/4 frequently over tied notes, which can be problematic. Practicing without ties and counting out loud may help until one is familiar with the rhythmic patterns. Overall the pianist must treat this piece as a symphonic work and prepare to play with full power and coloristic resources.

Book II

Eubie’s Blues

In 1969 Columbia Records issued a two-LP set called The Eighty-Six Years of Eubie Blake. He was an American composer and pianist of ragtime and jazz.[5] The LP set shows Blake’s marvelous talent as a pianist and composer. The mix of music, such as ragtime and tango, was included.[6] Boury immediately composed his own rags. He performed his rags in Toronto Ragtime Festival in 1971, and his rags were admired by Eubie Blake.[7]

This classic rag piece is a hybrid of rags and blues. It is in a slow, march-like tempo with some quicker harmonic rhythm. It has strong rhythmic counterpoint of accents and sophisticated melodic figuration. The countermelodies crop up in both treble and bass. Boury’s tempo indication “wilted” at the beginning specified that Eubie Blake’s career had passed its peak. In addition, the other tempo indication such as “slow & sadly” and “wind down to the end” support the blues mood. The form of this piece is A (mm1–18) – B(mm.19–45) – A(mm. 46–62) –coda(63–72). The syncopated rhythms with wider ranged chords in both hands require practicing. The bigger chords can be rolled on the beat. The pianist must keep in mind that the ragtime piece should never be played in a very fast tempo, or it would ruin the style of this piece

Stroller in Air

Boury dedicated this piece to his colleague, William Albright, who was also breaking out of the modern music syndrome with ragtime music. This title comes from a short story Le Piéton de l'air (A Stroll in the Air) by Eugène Ionesco, a Romanian-French dramatist. The story is about a contemporary person who sees a biplane from the time of the First World War fly over, and Boury thought that appropriate as a title since it was the height of the ragtime craze.

This is one of Boury’s longer works which is in a through-composed form. There is a subtitle, “a medley”, which refers to: “A collection of parts or passages of well‐known songs or pieces arranged so that the end of one merges into the start of the next”.[8] Boury stated that this movement was a series of his own musical sketches. Fundamentally, there are a total of five sections including an introduction and a coda; intro – A (mm. 11–36) – B (mm. 37–59) – C (mm. 60–75) – A’ (mm. 76–100) – Coda (mm. 101–113). Some of these sections include subtitles, such as “Wild Goose” and “Kingdom Come”. “Wild Goose” refers to the slang, “Wild Goose Chase”, endless chase, and “Kingdom Come” is a quote from “The Lord's Prayer”. Perhaps the composer intended this piece to show people’s feelings of sadness and depression caused by the war. The pianist must produce the introduction with emotionless sonority. Therefore, each chord in the introduction should be played without unnecessary accents or dynamical changes in the introduction. The first A section has very thick chords accompanied by octave in the lower register. Due to faster tempo the sound may get too harsh. The pianist must bring out the outer notes and not play all notes equally. In the section of “Wild Goose” there are four sets of ascending arpeggios. These may refer to the “endless chase” that never goes anywhere but to come back to the starting point. The result of the endless chase leads to a very dark and exhausted sound starting in measure in 50–. Four measures of the transition (mm. 56– 59) to “Kingdom Come” may be a ‘dark tunnel’ where people are searching for hope. “Kingdom Come” has a very consistent tempo until it reaches the next section. Perhaps it may describe that people unite together and believe that Kingdom will come if you are faithful to work every day. At measure 76 the first theme comes back, but starts slower and weaker in G minor compared to earlier first theme. This section could be the time people suffer in silence and pretend everything is okay. At measure 93 a G major chord might be expected to be played, followed by tonic and dominant chords in G major. Instead, Boury chose to write a g dim° chord with sforzando to surprise listeners. Adding a brief moment before playing the g dim° chord would give these notes, special emphasis. Here may be described as people reached to their emotional limit at g dim° chord, and lost their hopes at mm. 96– ("little by little lose steam"). In the coda, this war puts people in a very deep depression; in a zombie-like state where they seem to have no will of their own.

There are a few suggestions for learning and performing this piece. Many of the bigger chords may need to be rolled. The pianist must make sure to have the chords on the beat when rolling them. Additionally, this rolling motion must match the mood of the section. For the chromatic passages, use finger numbers 1 and 4 on the black-key octaves. This helps the pianist to shape the phrases better and also easier on the hands to do so without making mistakes.

I Left My Heart

San Francisco was Boury and his wife’s favorite city to visit in the West. Boury realized that the Prelude in E-flat Major, Op. 23, No. 6 by Sergei Rachmaninoff and I Left My Heart in San Francisco by George Cory were very similar. Boury decided to write recomposition version of those two famous works.

In Boury’s version he used Rachmaninoff’s prelude up to measure 21. In the following measure 22 the melody switches to I Left My Heart in San Francisco. Rest of the piece is a combination of both Rachmaninoff and Cory, with the exception of the ending which is the same ending as Rachmaninoff prelude.

References

- ↑ Robert Boury, “Faculty: Robert Boury”, http://www.ualr.edu/music/index.php/home/faculty/robert-boury. (Accessed July 29, 2009)

- ↑ Robert Boury, E-mail Interview, (July 29, 2009)

- ↑ A fast ballroom dance of American origin. It became popular in the 1890s. The steps, to a quick–quick–slow rhythm in each bar, were done with a gliding skip similar to that of the polka. Robert Boury, E-mail Interview, (June 02, 2010)

- ↑ Robert Boury, E-mail Interview, (June 02, 2010)

- ↑ David A. Jesen, Gordon Gene Jones, Black Bottom Stomp: Eight Masters of Ragtime and Early Jazz (Routledge, NY, Routledge, 2002): 46

- ↑ David A. Jesen, Gordon Gene Jones, Black Bottom Stomp: Eight Masters of Ragtime and Early Jazz (Routledge, NY, Routledge, 2002): 46-48

- ↑ Robert Boury, “Faculty: Robert Boury”, http://www.ualr.edu/music/index.php/home/faculty/robert-boury. (Accessed June 2, 2010)

- ↑ Michael Kennedy "Medley." In The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. rev., Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com./subscriber/article/opr/t237/e6675 (accessed December 11, 2011).