Polish–Czechoslovak border conflicts

Border conflicts between Poland and Czechoslovakia began in 1918 between the Second Polish Republic and First Czechoslovak Republic, both freshly created states. The conflicts centered on the disputed areas of Cieszyn Silesia, Orava Territory and Spiš. After World War II they broadened to include areas around the cities of Klodzko and Racibórz, which until 1945 had belonged to Germany. The conflicts became critical in 1919 and were finally settled in 1958 in a treaty between the People's Republic of Poland and Czechoslovakia.

Before World War I

Before the First World War both Spiš and Orava were multi-ethnic areas. The inhabitants of the northernmost parts of both lands were predominantly Gorals, whose dialect and customs were in many ways similar to those of the Podhale Gorals. Another Goral enclave was situated in Čadca area. At the end of 19th century tourism in and around the Tatra Mountains became very popular among the Polish educated public and the folklore of the Podhale Gorals was heavily romanticized by writers and artists. Because of their archaic Polish basis, the Goral dialects became a popular object of study among linguists dealing with the history of the Polish language.

As a result, by the end of the 19th century Polish intellectuals commonly saw the Goral speaking areas in Spiš, Orava and around Čadca as being ethnographically Polish just like Podhale, irrespective of their inhabitants' actual national consciousness (or lack of it). Actually, the Slovak national movement in these areas was older and stronger than Polish . The exception was northeastern Orava, with an influx of Polish or Polish-educated priests into the local Catholic parishes and some circulation of the Polish-language newspaper Gazeta Zakopiańska from nearby Podhale.

Creation of Poland and Czechoslovakia

After the end of World War I, both of the two newly created independent states of Second Polish Republic and First Czechoslovak Republic claimed the area of Cieszyn Silesia. Czechoslovakia claimed the area partly on historic and ethnic grounds, but especially on economic and strategic grounds. The disputed area was part of the historic lands of Bohemian Crown. The only railway from Czech territory to eastern Slovakia ran through this area (Košice-Bohumín Railway), and access to the railway was critical for Czechoslovakia: the newly formed country was at war with Béla Kun's revolutionary Hungarian Soviet Republic, which was attempting to re-establish Hungarian sovereignty over Slovakia. The area is also very rich in black coal, and it was the most industrialized region of all Austria-Hungary. The important Třinec Iron and Steel Works are also located here. All these raised the strategic importance of this region to Czechoslovakia. On the other hand, majority of the population was Polish, with substantial Czech and German minorities.

The Polish side based its claim to the area on ethnic criteria: a majority of the area's population was Polish according to the last (1910) Austrian census.[1]

Two local self-government councils, Polish and Czech, were created. Initially, both national councils claimed the whole of Cieszyn Silesia for themselves, the Polish Rada Narodowa Księstwa Cieszyńskiego in its declaration "Ludu śląski!" of 30 October 1918 and the Czech Národní výbor pro Slezsko in its declaration of 1 November 1918.[2] On 31 October 1918, in the wake of World War I and the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, most of the area was taken over by local Polish authorities. The short-lived interim agreement of 2 November 1918 reflected the inability of the two national councils to come to final delimitation,[2] and on 5 November 1918 the area was divided between Poland and Czechoslovakia by another interim agreement.[3] In 1919 the councils were absorbed by the newly created and independent central governments in Prague and Warsaw.

The inclusion of Spiš and Orava in the new state of Czechoslovakia was also not welcomed by all of its residents. In early November 1918 National Council of Poles in Upper Orava constituated itself in Jabłonka and pro-Polish Spisz National Council declared its existence in Stará Ľubovňa, both groups being in contact with Republic of Zakopane – a short (1 month) lived autonomous Polish statelet in Podhale, whose president was Stefan Żeromski. On 6 November 1918, Polish forces entered Spiš, but retreated after a defeat at Kežmarok on 7 December 1918 as well as pressure from the Entente. In June 1919, however, the Poles captured again northern Spiš and in addition northern Orava. In Spiš they demanded the whole northern half of the region down to Poprad, though units were withdrawn after orders from Warsaw in January 1919. Although both governments promised to carry out plebiscites in villages in northern Spiš and northeastern Orava about whether those people want to live in Poland or in Czechoslovakia, plebiscites were not held and both governments agreed to arbitration.

In Poland the case was advocated by Polish Tatra Society and later by National Committee for Defense of Spisz, Orawa, Czadca and Podhale established in Kraków and led by Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer, a popular writer known for his stories on Tatra mountains and Goral folklore. It's worth to notice, that the whole conflict was seen as Polish-Czech issue rather than Polish-Slovak, with phrases like "Czech invasion" in common use . The Committee organized a delegation, whose members - Ferdynand Machay, a priest born in Jabłonka (Orava), Piotr Borowy from Rabče (Orava) and Wojciech Halczyn from Lendak (Spiš) went to Paris and, during a personal audience, talked to president Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

Czechoslovak-Polish conflict in 1919

In January 1919 a war erupted between Second Polish Republic and First Czechoslovak Republic over the Cieszyn Silesia area in Silesia. The Czechoslovak government in Prague requested that the Poles cease their preparations for national parliamentary elections in the area that had been designated Polish in the interim agreement as no sovereign rule was to be executed in the disputed areas. The Polish government declined and the Czechoslovak side decided to stop the preparations by force. Czechoslovak troops entered area managed by Polish interim body on January 23. Czechoslovak troops gained the upper hand over the weaker Polish units. The majority of Polish forces were engaged in fighting with the West Ukrainian National Republic over eastern Galicia at that time. Czechoslovakia was forced to stop the advance by the Entente, and Czechoslovakia and Poland were compelled to sign a new demarcation line on February 3, 1919 in Paris.

At the Paris Peace Conference (1919), Poland requested northwesternmost Spiš (including the region around Javorina).

Negotiations of the 1920s

A final line was set up at the Spa Conference in Belgium. On July 28, 1920, the western part of the disputed territory was given to Czechoslovakia while Poland received the eastern part, thus creating a Zaolzie with a substantial Polish minority.

Edvard Beneš also agreed to cede to Poland 13 villages (especially Nowa Biała, Jurgów and Niedzica; 195 km²; pop. 8747) in northwestern Spiš and 12 villages in northeastern Orava (around Jabłonka; 389 km²; pop. 16133), in matter of fact the Czechoslovak authorities officially regarded their inhabitants as exclusively Slovak, while Poles pointed out that the dialect used there belonged to Polish language. The Polish government was not satisfied with this result.

The conflict was only resolved by the Council of the League of Nations (International Court of Justice) on 12 March 1924, which decided that Czechoslovakia should retain the territory of Javorina and Ždiar and which entailed (in the same year) an additional exchange of territories in Orava - the territory around Nižná Lipnica went to Poland, the territory around Suchá Hora and Hladovka went to Czechoslovakia. The new frontiers were confirmed by a Czechoslovak-Polish Treaty on 24 April 1925 and are identical with present-day borders.

Annexations by Poland in 1938

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was an important railway junction city of Bohumín. The Poles regarded the city as of crucial importance to the area and to Polish interests. On 28 September, Beneš composed a note to the Polish administration offering to reopen the debate surrounding the territorial demarcation in Těšínsko in the interest of mutual relations, but he delayed in sending it in hopes of good news from London and Paris, which came only in a limited form. Beneš then turned to the Soviet leadership in Moscow, which begun a partial mobilisation in eastern Belarus and the Ukrainian SSR and threatened Poland with the dissolution of the Soviet-Polish non-aggression pact.[4]

Nevertheless, the Polish leader, Colonel Józef Beck believed that Warsaw should act rapidly to forestall the German occupation of the city. At noon on 30 September, Poland gave an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government. It demanded the immediate evacuation of Czechoslovak troops and police and gave Prague time until noon the following day. At 11:45 a.m. on 1 October the Czechoslovak foreign ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that Poland could have what it wanted. The Polish Army, commanded by General Władysław Bortnowski, annexed an area of 801.5 km² with a population of 227,399 people.

The Germans were delighted with this outcome. They were happy to give up a provincial rail centre to Poland; it was a small sacrifice indeed. It spread the blame of the partition of Czechoslovakia, made Poland a seeming accomplice in the process and confused the issue as well as political expectations. Poland was accused of being an accomplice of Nazi Germany – a charge that Warsaw was hard put to deny.[5]

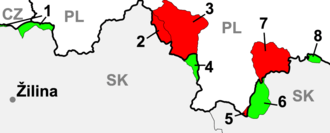

Poland occupied some northern parts of Slovakia and received from Czechoslovakia Zaolzie, territories around Suchá Hora and Hladovka, around Javorina, and in addition the territory around Lesnica in the Pieniny Mountains, a small territory around Skalité and some other very small border regions (they officially received the territories on 1 November 1938 (see also Munich Agreement and First Vienna Award).

World War II

The First Slovak Republic received back both the territories lost in 1938 and annexed the territories "lost" in 1920–1924. This re-annexation happened in October 1939 (officially confirmed on 24 November 1939) when Slovakia supported Nazi Germany's attack on Poland in September 1939. The annexation by the puppet state of Slovakia saved the population of the area from the naked terror of Nazi Germany as it was practised in the General Government until Slovakia agreed to take part in the Holocaust, but even then the genocidal policy was directed exclusively against the Jews and Gypsies.[6]

In January 1945, these border territories were liberated by the Soviet Red Army. The inhabitants of Orava and Spiš (including the territories "lost" by Czechoslovakia in 1920–1924) created authorities similar to those in the remaining Czechoslovakia (Slovakia ceased to exist as an independent state) and sought to prevent Polish authorities, which were trying to recover the territories they had before World War II, from entering the region .. The Czechoslovak President Beneš, however, decided to give the territories regained during World War II (i. e. northern Spiš and northern Orava) to Poland again (the corresponding formal act was signed on 20 May 1945), although Slovak organised poll on the territories showed support of the population in favour of Czechoslovakia. There were many protests in the form of delegations visiting the president, petitions to Prague and Poland, protests by American Slovaks and protests by the Slovak clergy.[7] Despite these, on 20 May 1945, the pre-World War II borders between Czechoslovakia and Poland were restored.

Aftermath

In 1945 the border between Poland and Czechoslovakia was set at the 1920 line.[8]

Polish troops then occupied northern Orava and Spiš on 17 July 1945. There were armed clashes and fatalities in some villages over the following two years. Slovaks from the Polish part of Spiš settled mainly in the newly created industrial town of Svit near Poprad, Kežmarok, Poprad, and in depopulated German villages (from which the German inhabitants had been previously expelled) near Kežmarok. Slovaks from the Polish part of Orava settled mainly in Czech Silesia, and in depopulated German villages in the Czech lands (Sudetenland).

On 10 March 1947 a treaty guaranteeing basic rights for Slovaks in Poland was signed between Czechoslovakia and Poland. As a result, 41 Slovak basic schools and 1 high school were opened in Poland. Most of these however were shut down in the early sixties because of lack of Slovakian teachers.

On June 13, 1958, in Warsaw, the two countries signed a treaty confirming the border at the line of January 1, 1938 (that is, returning to the situation before the Nazi-imposed Munich Agreement transferred territory from Czechoslovakia to Poland), and since then there have been no conflicts regarding this matter.

In March 1975 Czechoslovakia and Poland modified their border along the Dunajec to permit Poland to construct a dam in the Czorsztyn region, southeast of Kraków.[9]

The present era

In 2002, Poland and Slovakia made some further minor border adjustments:

Territory of the Republic of Poland with a total area of 2,969 m2, including:

a) in the area of a viewing tower on the surface of the saddle Dukielskie about 376 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 2

b) unnamed area on the island with an area of 2,289 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 3

c) in the Polish village Jaworzynka region with an area of 304 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 4, including real estate, equipment and plants are transferred to the ownership of the Slovak Republic.

Territory of the Slovak Republic with an area of 2,969 m2, including:

a) in the area of a viewing tower on Dukielskie enters an area of 376 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 2

b) Nokiel on the island with an area of 2,289 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 3c) in the Slovak village Skalité region with an area of 304 m2, according to documents limit referred to in Article 1, paragraph 4, including real estate, equipment and plants are transferred to the ownership of the Republic of Poland.

— Dziennik Ustaw z 2005 r. Nr 203 poz. 1686.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Zahradnik 1992, 178-179.

- 1 2 Gawrecká 2004, 21.

- ↑ Zahradnik 1992, 52.

- ↑ The Munich Crisis, 1938 by Igor Lukes and Erik Goldstein, page 61

- ↑ Watt 1998, 386.

- ↑ See, Stanley S.Seidner, Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz Rydz and the Defense of Poland, New York, 1978, 134.

- ↑ Irene Matasovsky Matuschak, The Abandoned Ones: The Tragic Story of Slovakia's Spis and Orava Regions, 1919-1948

- ↑ http://ioh.pl/artykuly/pokaz/konflikt-graniczny-polskoczechosowacki-w-latach,1076/

- ↑ "Dunajec River". britannica.com. 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ↑ "Official text of the treaty". Retrieved 2007-09-26. Dziennik Ustaw z 2005 r. Nr 203 poz. 1686 (Polish)

Further reading

- Gąsiorowski, Zygmunt J. "Polish-Czechoslovak Relations, 1918-1922," Slavonic and East European Review (1956) 35#84 pp. 172–193 in JSTOR

- Gawrecká, Marie (2004). Československé Slezsko mezi světovými válkami 1918-1938. Opava: Silesian University in Ostrava. ISBN 80-7248-233-5.

- Gromada, Thaddeus V. "Slovak Nationalists and Poland during the Interwar Period, Jednota Annual Furdek (1979), Vol. 18, pp 241-253.

- Volokitina, T. V. "The Polish--Czechoslovak Conflict over Teschen: The Problem of Resettling Poles and the Position of the USSR," Journal of Communist Studies & Transition Politics (2000) 16#1 pp 46–63

- Woytak, Richard A. "Polish Military Intervention into Czechoslovakian Teschen and Western Slovakia in September–November 1938," East European Quarterly (1972) 6#3 pp 376–387.

- Zahradnik, Stanisław; Marek Ryczkowski (1992). Korzenie Zaolzia. Warszawa - Praga - Trzyniec: PAI-press. OCLC 177389723.