Borrowing base

| Accounting |

|---|

|

|

Major types |

|

Selected accounts |

|

People and organizations

|

|

Development |

|

|

Borrowing base is an accounting metric used by financial institutions to estimate the available collateral on a borrower's assets in order to evaluate the size of the credit that may be extended.[1] Typically, the calculation of borrowing base is used for revolving loans, and the borrowing base determines the maximum credit line available to the borrower.[2][3] Occasionally, borrowing base is also used to determine the maximum size of a term loan. Depending on the contractual terms of the loan, the assets included in the calculation of the borrowing base may be used as collateral for the loan.[4]

Borrowing base calculation

For corporations and small businesses

Borrowing base is frequently used for asset-based commercial loans offered by banks to corporations and small businesses.[5] In this case, borrowing base of a business is typically calculated of corporation's accounts receivable and of its inventory.[6] Work in process is excluded from borrowing base.[7] In addition, also excluded are the accounts receivable from bankrupt customers[8] and accounts receivable that are too old[9] — usually over 90 days past due[10] (in some cases over 120 days past due.[11])

Different proportions (or 'advance rates') of accounts receivable and of the inventory are included into borrowing base. Typical industry standards are 75%—85% for accounts receivable[1][12] and 25%—60% for inventory,[7] and the advance rates can vary dramatically depending on the circumstances.[1]

Lenders' methods of assessment of the inventory value vary. A lender can hire an independent contractor to evaluate borrower's inventory[13] or use averaging, adjusted for a particular industry. For example, Moody's is reportedly applying Monte-Carlo method over inventory price fluctuations within each industry to determine risk free advance rates.[14]

| Assets | Typical advance rate | Factors that increase advance rate | Factors that decrease advance rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accounts receivable | 75%—85%[1][12] | diversification of accounts receivable[1] | errors in borrower's reports;[15] bad credit history of the payees;[6] |

| Inventory | 25%—60%[7] (or up to 85% of its net liquidation value.[12]) | errors in borrower's reports;[15] inventory aged, out of date, or unpacked[6] | |

| Commodities | Up to 90%[1] | volatility of the commodity price[16] |

Past due accounts payable are typically subtracted from the borrowing base.[17]

In case of revolving loans, lenders demand periodic recalculations of borrowing base and subsequently adjust the credit limit. Traditionally, banks recalculated borrowing base for businesses yearly, biannually, or monthly.[18] In recent years, however, such 'fixed' borrowing base is deemed risky, as company's assets fluctuate in time.[1][19] This consideration and the advancement of computer technology prompted weekly[20] and daily[21] recalculations of borrowing base.[22] Regardless of the need of a loan, recurrent calculations of its own borrowing base is currently one of the accounting best practices.[23]

For financial institutions

Borrowing base of financial institutions who themselves apply for asset-based revolving loans is calculated by summing up all tangible working assets (typically cash, bonds, stocks, etc.) and subtracting from it all senior debt, i.e. all other accumulated debt that does not rank behind other debt for repayment in the event of a liquidation.[24]

For government organizations

Borrowing base of government organizations is calculated similar to that of corporations. However, in many cases there are government restrictions on pledges of some or all of the accounts receivable. Such accounts receivable are excluded from the borrowing base.[6]

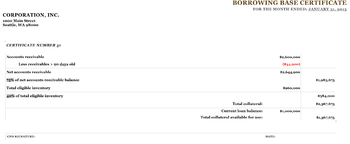

Borrowing base certificates

Borrowing base certificate is the official accounting document prepared by the borrower that certifies the size of the borrowing base of an organization with the previously agreed advance rates.[11] Borrowing base certificate includes a summary calculation sheet. In its paper form, a borrowing base certificate is signed by the authorized representative of the organization, typically by the organization's CFO, as errors in the calculation of borrowing base can result in various penalties (loan interest rate increase, demand of early loan repayment, etc.)[25][26]

As lenders demand the submission of borrowing base certificates more frequently (weekly[20] or even daily[21]), software applications become available that can automate these submissions. For example, BBC Easy application automates these submissions for small businesses.[27]

Junior and senior borrowing bases

Junior borrowing base and senior borrowing base are calculated for the financial institutions and large corporations which have structured debt. In these cases, senior borrowing base is associated with senior debt and calculated of all assets. On the other hand, junior borrowing base is associated with junior debt and calculated of assets that are not already pledged for senior debts.[28][29] Thus junior borrowing base is always smaller than senior borrowing base.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kazemi, Black & Chambers 2016, p. 825.

- ↑ Taylor & Sansone 2006, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Marks et al. 2005, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Koch & MacDonald 2014, p. 569.

- ↑ Taylor & Sansone 2006, pp. 254, 272.

- 1 2 3 4 Marks et al. 2005, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 Wiersema 2006, p. 29.03.

- ↑ Bragg 2010, p. 161.

- ↑ Whitney 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ Wiersema 2006, p. 29.01.

- 1 2 Marks et al. 2005, p. 203.

- 1 2 3 Bagaria 2016, p. 69.

- ↑ Bagaria 2016, pp. 68–70.

- ↑ Fabozzi & Choudhry 2004, p. 266.

- 1 2 Bragg 2010, p. 311.

- ↑ Fabozzi & Choudhry 2004, pp. 266–268.

- ↑ Wiersema 2006, pp. 29.03–29.04.

- ↑ Nassberg 1981, pp. 843–845.

- ↑ Fabozzi & Choudhry 2004, pp. 266–267.

- 1 2 Marks et al. 2005, p. 291.

- 1 2 Schroeder & Tomaine 2007, p. 285.

- ↑ DeYoung & Hunter 2002, p. 210.

- ↑ Bragg 2010, p. 107.

- ↑ Terry 2000, p. 816.

- ↑ Bragg 2012, pp. 260–264, 364–380.

- ↑ Milad 2010, p. 14.

- ↑ Keeton 2013.

- ↑ Marks et al. 2005, p. 208.

- ↑ Whitman & Diz 2013, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Whitman & Diz 2013, p. 51.

Literature cited

- Bagaria, Rajay (March 28, 2016). Buchman, Emil, ed. High Yield Debt: An Insider's Guide to the Marketplace. Wiley Finance. John Wiley & Sons. ASIN 1119134412. ISBN 1119134439. LCCN 2015042482. OCLC 931227000.

- Bragg, Steven M. (29 January 2010) [1999]. Accounting Best Practices. Wiley Best Practices (6th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0470561653. LCCN 2009047249. OCLC 746577431.

- Bragg, Steven M. (2012). Accounting Policies and Procedures Manual: A Blueprint for Running an Effective and Efficient Department (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ASIN B008NC0WC8. ISBN 1118428668. OCLC 864912888.

- DeYoung, Robert; Hunter, William C. (September 30, 2003). "Chapter 10: The Future of Relationship Lending". In Gup, Benton E. The Future of Banking. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 203–228. ISBN 1567204678. LCCN 2002023035.

- Fabozzi, Frank J.; Choudhry, Moorad (March 4, 2004). The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products. Frank J. Fabozzi. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ASIN 0471484156. ISBN 0471662070. LCCN 2004273765. OCLC 54712778.

- Kazemi, Hossein B.; Black, Keith H.; Chambers, Donald R. (October 10, 2016). CAIA Level II: Advanced Core Topics in Alternative Investments (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ASIN 1119016398. ISBN 1119016398. OCLC 918590725.

- Keeton, Ann (April 3, 2013). "Numerica Credit Union Adopts C&I Lending Program". Credit Union Times. ISSN 1058-7764. OCLC 867675674.

- Koch, Timothy W.; MacDonald, S. Scott (September 11, 2014). Bank Management (8th ed.). Australia: Cengage Learning. ISBN 1133494684. LCCN 2014940665.

- Marks, Kenneth H.; Robbins, Larry E.; Fernandez, Gonzalo; Funkhouser, John P. (April 1, 2005). The Handbook of Financing Growth: Strategies and Capital Structure. Wiley Finance (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471726311. LCCN 2004024107. OCLC 56753022.

- Milad, Anis I. (February 18, 2010). Business Management Handbook Paperback. AuthorHouse. ISBN 1449086608.

- Nassberg, Richard T. (1981). "Loan Documentation: Basic But Crucial". The Business Lawyer: a bulletin of the Section on Corporation, Banking, and Mercantile Law. Chicago, IL: American Bar Association. 36 (3): 843–934. ISSN 0007-6899. JSTOR 40686220. LCCN 88019740. OCLC 60617274. (subscription required (help)).

- Schroeder, Gilbert J.; Tomaine, John J. (2007). Loan Loss Coverage Under Financial Institution Bonds. American Bar Association. ISBN 1590319435. LCCN 2007282718. OCLC 182518909.

- Taylor, Allison; Sansone, Alicia (August 18, 2006). The Handbook of Loan Syndications and Trading. McGraw Hill Professional. ASIN 0071468986. ISBN 0071468986. LCCN 2006006606. OCLC 64770803.

- Terry, Brian J. (June 1, 2000) [1997]. The International Handbook of Corporate Finance. Glenlake Business Reference Books (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ASIN 188899830X. ISBN 0814425089. LCCN 00699817. OCLC 48139916.

- Whitman, Martin J.; Diz, Fernando (May 20, 2013). Modern Security Analysis: Understanding Wall Street Fundamentals. Wiley Finance (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ASIN 1118390040. ISBN 1118603389. LCCN 2013000737. OCLC 824120039.

- Whitney, John O. (January 19, 1998) [1987]. Taking Charge: Management Guide to Troubled Companies and Turnarounds. Washington DC: Beard Books. ASIN 1893122034. ISBN 1893122034. OCLC 642999540.

- Wiersema, William (April 14, 2006). Manufacturing, Distribution and Retail Guide. Chicago, IL: CCH. ASIN 0808090240. ISBN 0808090240. OCLC 163811021.