Break bulk cargo

In shipping, break bulk cargo or general cargo are goods that must be loaded individually, and not in intermodal containers nor in bulk as with oil or grain. Ships that carry this sort of cargo are often called general cargo ships. The term break bulk derives from the phrase breaking bulk—the extraction of a portion of the cargo of a ship or the beginning of the unloading process from the ship's holds. These goods may not be in shipping containers. Break bulk cargo is transported in bags, boxes, crates, drums, or barrels. Unit loads of items secured to a pallet or skid are also used.[1]

A break-in-bulk point is a place where goods are transferred from one mode of transport to another, for example the docks where goods transfer from ship to truck.

Break bulk was the most common form of cargo for most of the history of shipping. Since the late 1960s the volume of break bulk cargo has declined dramatically worldwide as containerization has grown. Moving cargo on and off ship in containers is much more efficient, allowing ships to spend less time in port. Break bulk cargo also suffered from greater theft and damage.

Loading and unloading

Although cargo of this sort can be delivered straight from a truck or train onto a ship, the most common way is for the cargo to be delivered to the dock in advance of the arrival of the ship and for the cargo to be stored in warehouses. When the ship arrives the cargo is then taken from the warehouse to the quay and then lifted on board by either the ship's gear (derricks or cranes) or by the dockside cranes. The discharge of the ship is the reverse of the loading operation.

Loading and discharging by break bulk is labour-intensive. The cargo is brought to the quay next to the ship and then each individual item is lifted on board separately. Some items such as sacks or bags can be loaded in batches by using a sling or cargo net and others such as cartons can be loaded onto trays before being lifted on board. Once on board each item must be stowed separately.

Before any loading takes place, any signs of the previous cargo are removed. The holds are swept, washed if necessary and any damage to them repaired. Dunnage is laid ready for the cargo or is just be put in bundles ready for the stevedores to lay out as the cargo is loaded.

There are many sorts of break bulk cargo but amongst them are:

Bagged cargo

Bagged cargo (e.g. coffee in sacks) is stowed on double dunnage and kept clear of the ship's sides and bulkheads. Bags are kept away from pillars and stanchions by covering it with matting or waterproof paper.[2]

Baled goods

Baled goods are stowed on single dunnage at least 50 mm (1.97 in) thick. The bales must be clean with all the bands intact. Stained or oily bales are rejected. All fibres can absorb oil and are liable to spontaneous combustion. As a result, they are kept clear of any new paintwork. Bales close to the deckhead are covered to prevent damage by dripping sweat.[3]

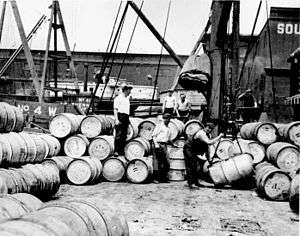

Barrels and casks

Wooden barrels are stowed on their sides on "beds" of dunnage which keeps the middle of the side (the bilge) off the deck and they are stowed with the bung at the top. To prevent movement wedges called quoins are put in on top of the "beds". Barrels should be stowed fore and aft and not athwart ships. Once the first tier has been loaded the next tier of barrels fits into the hollows between the barrels, this is known as stowing "bilge and cantline".[4] Barrels which are also known as casks or tuns are primarily use for transporting liquids such as wine, water, brandy, whiskey, and even oil. They are usually built in spherical shape to make it easier to roll and have less friction when changing direction.

Corrugated boxes

Corrugated boxes are stowed on a good layer of dunnage and kept clear of any moisture. Military and weather resistant grades of corrugated fiberboard are available. They are not overstowed with anything other than similar boxes. They are frequently loaded on pallets to form a unit load; if so the slings that are used to load the cargo are frequently left on to facilitate discharge.[5]

Wooden shipping containers

Wooden boxes or crates are stowed on double dunnage in the holds and single dunnage in the 'tween decks. Heavy boxes are given bottom stowage. The loading slings are often left on to aid discharge.[5]

Drums

_March_2016.jpg)

Metal drums are stowed on end with dunnage between tiers, in the longitudinal space of the ship [6]

Paper reels

Reels or rolls are generally stowed on their sides and care is taken to make sure they are not crushed.[7]

Motor vehicles

Automobiles are lifted on board and then secured using lashings. A great deal of care is taken to make sure they do not get damaged.[8] Vehicles are also prepared by ensuring potentially hazardous liquids (gasoline, etc.) have been removed. (This is in contrast to Ro-ro (Roll-on/roll-off) vessels where vehicles are driven on and off the ship on their own wheels.)

Steel girders

Any long heavy items are stowed fore and aft. If they are stowed athwart ships they are liable to shift if the ship rolls heavily and pierce the side of the ship.

Advantages and disadvantages

The biggest disadvantage with break bulk is that it requires more resources at the wharf at both ends of the transport—longshoremen, loading cranes, warehouses, transport vehicles—and often takes up more dock space due to multiple vessels carrying multiple loads of break bulk cargo. Indeed, the decline of break bulk did not start with containerisation; rather, the advent of tankers and bulk carriers reduced the need for transporting liquids in barrels and grains in sacks. Such tankers and carriers use specialised ships and shore facilities to deliver larger amounts of cargo to the dock and effect faster turnarounds with fewer personnel once the ship arrives; however, they do require large initial investments in ships, machinery, and training, slowing their spread to areas where funds to overhaul port operations and/or training for dock personnel in the handling of cargo on the newer vessels may not be available. As modernization of ports and shipping fleets spreads across the world, the advantages of using containerization and specialized ships over break-bulk has sped the overall decline of break-bulk operations around the world. In all, the new systems have reduced costs as well as spillage and turnaround times; in the case of containerisation, damage and pilfering as well.

Break bulk continues to hold an advantage in areas where port development has not kept pace with shipping technology; break-bulk shipping requires relatively minimal shore facilities—a wharf for the ship to tie to, dock workers to assist in unloading, warehouses to store materials for later reloading onto other forms of transport. As a result, there are still some areas where break-bulk shipping continues to thrive. Goods shipped break-bulk can also be offloaded onto smaller vessels and lighters for transport into even the most minimally-developed port where the normally large container ships, tankers, and bulk carriers might not be able to access due to size and/or water depth. In addition, some ports capable of accepting larger container ships/tankers/bulk transporters still require goods to be offloaded in break-bulk fashion; for example, in the outlying islands of Tuvalu, fuel oil for the power stations is delivered in bulk but has to be offloaded in barrels.[9]

References

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 31. ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 32: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 33: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 35: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- 1 2 Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 37: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 38: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 39: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Notes on Cargo Work by J. F. Kemp and Peter Young, 1971 (3rd edition); page 40: ISBN 0-85309-040-8.

- ↑ Tuvalu Electricity Corporation Presentation, Taaku Sekielu and Polu Tanei (PDF)

Further reading

- Marc Levinson, The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger (Princeton Univ. Press 2006).

- Sauerbier, Charles L.; Meurn, Robert J. (2004). Marine cargo operations: a guide to stowage. Cambridge, Md: Cornell Maritime Press. ISBN 0-87033-550-2.