Combined DNA Index System

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

| Physiological sciences |

| Social sciences |

| Forensic criminalistics |

| Digital forensics |

| Related disciplines |

| Related articles |

Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) is the United States national DNA database created and maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. CODIS consists of three levels of information; Local DNA Index Systems (LDIS) where DNA profiles originate, State DNA Index Systems (SDIS) which allows for laboratories within states to share information, and the National DNA Index System (NDIS) which allows states to compare DNA information with one another.

The CODIS software contains multiple different databases depending on the type of information being searched against. Examples of these databases include, missing persons, convicted offenders, and forensic samples collected from crime scenes. Each state, and the federal system, has different laws for collection, upload, and analysis of information contained within their database. However, for privacy reasons, the CODIS database does not contain any personal identifying information, such as the name associated with the DNA profile. The uploading agency is notified of any hits to their samples and are tasked with the dissemination of personal information pursuant to their laws.

Origins

CODIS was an outgrowth of the Technical Working Group on DNA Analysis Methods (TWGDAM, now SWGDAM) which developed guidelines for standards of practice in the United States and Canadian crime laboratories as they began DNA testing in the late 1980s.

TWGDAM was sponsored by the FBI Laboratory which hosted several scientific meetings a year at Quantico, Virginia, to accelerate development of laboratory guidelines and peer-reviewed papers to support forensic DNA testing which was, to some, an unproven forensic tool. TWGDAM completed a white paper in October 1989 which provided conceptual and operational concepts for a Combined DNA Index System to share DNA profiles among crime laboratories similarly to automated fingerprint identification which had become commonplace in law enforcement during the 1980s.

The FBI Laboratory began a pilot project with six state and local crime laboratories to develop software to support each laboratory's DNA testing and allow sharing of DNA profiles with other crime laboratories.

The DNA Identification Act of 1994 (42 U.S.C. §14132) authorized the establishment of this National DNA Index. The DNA Act specifies the categories of data that may be maintained in NDIS (convicted offenders, arrestees, legal, detainees, forensic (casework), unidentified human remains, missing persons and relatives of missing persons) as well as requirements for participating laboratories relating to quality assurance, privacy and expungement.

The DNA Identification Act, §14132(b)(3), specifies the access requirements for the DNA samples and records “maintained by federal, state, and local criminal justice agencies (or the Secretary of Defense in accordance with section 1565 of title 10, United States Code)” …and “allows disclosure of stored DNA samples and DNA analyses only— (A) to criminal justice agencies for law enforcement identification purposes; (B) in judicial proceedings, if otherwise admissible pursuant to applicable statutes or rules; (C) for criminal defense purposes, to a defendant, who shall have access to samples and analyses performed in connection with the case in which such defendant is charged; or (D) if personally identifiable information is removed, for a population statistics database, for identification research and protocol development purposes, or for quality control purposes.”

Federal law requires that laboratories submitting DNA data to NDIS are accredited by a nonprofit professional association of persons actively engaged in forensic science that is nationally recognized within the forensic science community. The following entities have been determined to satisfy this definition: the American Society of Crime Laboratory Directors/Laboratory Accreditation Board (ASCLD/LAB) and Forensic Quality Services (ANSI-ASQ National Accreditation Board FQS).

Scientific basis

Identification using CODIS relies on short tandem repeats (STR) that are present in the human genome. These two to six nucleotides are highly susceptible to copy-number variation polymorphisms.[1] STR loci can be amplified using PCR, and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The size of the DNA fragment is proportional to the number of repeats. Therefore, the number of repeats can be quantified, and the combination of repeats at each locus provides a distinctive genetic fingerprint for each individual.[2]

Markers

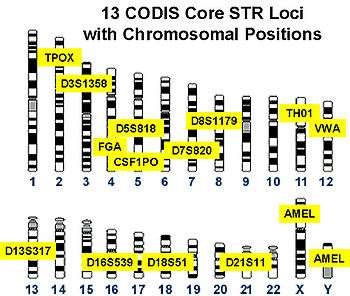

CODIS identifies genetic markers at 13 STR loci, plus Amelogenin (AMEL) to determine sex.

- CSF1PO

- D3S1358

- D5S818

- D7S820

- D8S1179

- D13S317

- D16S539

- D18S51

- D21S11

- FGA

- THO1

- TPOX

- vWA

These markers do not overlap with the ones commonly used for genealogical DNA testing. Some may be indicative of genetic diseases.[3]

Indices and database structure

CODIS is an index of pointers to assist US public crime laboratories to compare and exchange DNA profiles. A record in the CODIS database, known as a CODIS DNA profile, consists of an individual's DNA profile, together with the sample's identifier and an identifier of the laboratory responsible for the profile. CODIS is not a criminal history database, like the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), and does not contain any personal identity information, such as names, dates of birth, and social security numbers.

Originally, CODIS consisted of the Convicted Offender Index and the Forensic Index, but in recent years, the Arrestee Index, the Missing or Unidentified Persons Index, and the Missing Persons Reference Index have been added. The Convicted Offender Index contains profiles of individuals convicted of crimes. State law governs which specific crimes are eligible for CODIS. (All 50 states have passed DNA legislation authorizing the collection of DNA profiles from convicted offenders for submission to CODIS.) The Forensic Index contains profiles developed from biological material found at crime-scenes.

CODIS has a matching algorithm that searches the various indexes against one another according to strict rules that protect personal privacy. In solving rapes and homicides, for example, CODIS searches the Forensic Index against itself and against the Offender Index. A Forensic to Forensic match provides an investigative lead that connects two or more previously unlinked cases. A Forensic to Offender match actually provides a suspect for an otherwise unsolved case. It is important to note that the CODIS matching algorithm only produces a list of candidate matches. Each candidate match is confirmed or refuted by a Qualified DNA Analyst. (To become Qualified, a DNA Analyst must meet specific education and experience requirements and undergo semi-annual proficiency tests administered by a third party.)

CODIS databases exist at the local, state, and national levels. This tiered architecture allows crime laboratories to control their own data—each laboratory decides which profiles it will share with the rest of the country. As of 2006, approximately 180 laboratories in all 50 states participate in CODIS. At the national level, the National DNA Index System, or NDIS, is operated by the FBI at an undisclosed location.

Relative size

The National DNA Index (NDIS) contains over 12,010,904 offender profiles, 2,157,394 arrestee profiles and 663,191 forensic profiles as of October 2015. Ultimately, the success of the CODIS program will be measured by the crimes it helps to solve. CODIS’ primary metric, the “Investigation Aided,” tracks the number of criminal investigations where CODIS has added value to the investigative process. As of October 2015, CODIS has produced over 300,050 hits assisting in more than 285,447 investigations.

Controversies

Privacy concerns

The CODIS database originally was primarily used to collect DNA of convicted sex offenders. Over time, this has expanded. Currently all fifty states have mandatory DNA collection from certain felony offenses such as sexual assault and homicide. Other states have gone further in collecting DNA samples from juveniles and all suspects arrested.[4] In California, as a result of Proposition 69 in 2004, all suspects arrested for a felony, as well as some individuals convicted of misdemeanors, had their DNA collected starting in 2009. In addition to this, all members of the US Armed Services who are convicted at a Special court martial and above are ordered to provide DNA samples, even if their crime has no civilian equivalent (for example adultery).

Currently, the ACLU is concerned with the increased use of collecting DNA from arrested suspects rather than DNA testing for convicted felons. Along with the ACLU, civil libertarians oppose the use of a DNA database for privacy concerns as well as possible institutionalized discrimination policies in collection.

In popular culture

In forensics television series such as CSI, Bones, NCIS, Numb3rs, Criminal Minds, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, Rizzoli & Isles and Dexter, the investigators often match DNA with the CODIS database. These media representations have had a considerable effect on how members of the public, but also professionals within the criminal justice system, and even prisoners, view the utility of DNA databases.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Repnikova, Elena A.; Rosenfeld, Jill A.; Bailes, Andrea; Weber, Cecilia; Erdman, Linda; McKinney, Aimee; Ramsey, Sarah; Hashimoto, Sayaka; Lamb Thrush, Devon; Astbury, Caroline; Reshmi, Shalini C.; Shaffer, Lisa G.; Gastier-Foster, Julie M.; Pyatt, Robert E. "Characterization of copy number variation in genomic regions containing STR loci using array comparative genomic hybridization". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 7 (5): 475–481. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2013.05.008.

- ↑ Butler, John M. "Genetics and Genomics of Core Short Tandem Repeat Loci Used in Human Identity Testing". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 51 (2): 253–265. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00046.x.

- ↑ "Association of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene polymorphism with schizophrenia in the population of central Poland". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. August 26, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ↑ http://moritzlaw.osu.edu/students/groups/osjcl/files/2013/12/16.-Roth.pdf

- ↑ Machado H, Prainsack B (2012): Tracing Technologies: Prisoners’ Views in the Era of CSI. Farnham: Ashgate

External links

- CODIS page on FBI.gov. Accessed May 27, 2015.

- "ACLU Warns of Privacy Abuses in Government Plan to Expand DNA Databases". ACLU. March 1, 1999.

- A Not So Perfect Match, CBS, 2007

- "Anne Pressly: Detailed Cases and Informed Opinions On DNA". December 4, 2008.

- "DNA didn't prove anything, as it only had five points out of 13. Juror Explains Verdict In Double Murder". November 13, 2008.