Cape lion

| Cape Lion | |

|---|---|

| |

| Only known photo of a live Cape Lion, ca. 1860 in Jardin des Plantes, Paris, France | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo |

| Subspecies: | †P. l. melanochaitus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera leo melanochaitus Ch. H. Smith, 1858 | |

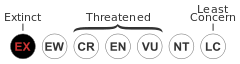

The Cape lion is possibly an extinct subspecies of lion with the taxonomic name Panthera leo melancholaitus, or a former population of Southern African lions, as in Southeast (Panthera leo krugeri) or Southwest African lions (Panthera leo bleyenberghi).[1][2][3]

Taxonomy

As with the Barbary lion, several people and institutions claim to have Cape lions. There is much confusion between Cape lions and other dark-coloured long-maned captive lions. Dark-maned lions in captivity today have been bred and cross-bred from lions captured in Africa long ago, with examples from all of these 'subspecies'. Mixed together, hybridized, most of today's captive lions have a 'soup' of alleles from many different lion subspecies.[4]

Early authors justified 'distinct' subspecific status of the Cape lion because of the seemingly fixed external morphology of the lions. Males had a huge mane extending behind their shoulders and covering the belly, and the lions' ears also had distinctive black tips. However, nowadays it is known that various extrinsic factors, including the ambient temperature, influence the colour and size of a lion's mane.[5] Results of mitochondrial DNA research published in 2006 do not support the 'distinctness' of the Cape lion. It may be that the Cape lion was only the southernmost population of the extant Transvaal lion, or it was closely related to Kalahari lions (either Panthera leo krugeri or Panthera leo bleyenberghi), a number of which had black manes (Rodrigues, 1997).[1][2][3][6]

Physical description

.jpg)

The Cape lion was thought by some people to have been large or heavy compared to other Sub-Saharan African lions,[7] but smaller than the North African lion,[8] though this may not have always been the case.[3][9][10][11] It was distinguished by its thick, black mane with a tawny fringe around the face. The tips of the ears were also black.[7] Besides Atlas lions, they had the "most luxuriant and extensive manes" amongst lions, with "tresses on flanks and abdomen," according to Hepnter and Sludskii (1972).[12]

Lions approaching 272 kg (600 pounds) were shot south of the Vaal River (Pease, 1913, page 91).[13] An emasculated lion in Surrey Zoological Gardens, brought from Kaffraria, was described by Jardine (1834) as being "much larger than either the Barbary or Persian lion."[11]

Behaviour and diet

Cape lions preferred to hunt large ungulates including antelopes, but also zebras, giraffes and buffaloes. They would also kill donkeys and cattle belonging to the European settlers. Man-eating Cape lions appear to have generally been old individuals with bad teeth.[7]

Habitat and extinction

'Black-maned' Cape lions ranged along the Cape of Africa on the southern tip of the continent. The Cape lion was not the only subspecies of lion, or population of Transvaal lions, living in South Africa, and its exact range is unclear. Its stronghold was Cape Province, in the area around Cape Town. One of the last Cape lions seen in the province was killed in 1858; in 1876 Czech explorer Emil Holub bought a young lion who died two years later.[14]

The Cape lion disappeared so rapidly following contact with Europeans that it is unlikely that habitat destruction was a significant factor. The Dutch and English settlers, hunters, and sportsmen simply hunted it into extinction.

Possible descendants and look-alikes

In 2000, specimens asserted to be descendants of Cape lions were found in captivity in Russia and two of them were brought to South Africa.[15] South African zoo director John Spence reportedly was long fascinated by stories of these grand lions scaling the walls of Jan van Riebeeck's castle in the 17th century. He studied van Riebeeck's journals to discern Cape lions' features, which include a long black mane, black in their ears, and larger size. He believed some Cape lions might have been taken to Europe and interbred with other lions. His 30-year search led to his discovery of black-maned lions closely resembling Cape lions at the Novosibirsk Zoo in Siberia, in 2000.[15][16] Besides having a black mane, the specimen that attracted Spence had a "wide face and sturdy legs." Novosibirsk Zoo's population, which had 40 cubs over a 30-year period, continues, and Spence was allowed to bring two cubs back to his zoo in South Africa. Back in South Africa, Spence explained that he hoped to breed lions that at least looked like Cape lions, and also hoped to have DNA testing done to establish whether the cubs were descendants.[17] Spence died in 2010 and the zoo closed in 2012, with the lions expected to go to Drakenstein Lion Park.[18]

References

- 1 2 Yamaguchi, N. (2000). The Barbary lion and the Cape lion: their phylogenetic places and conservation. African Lion Working Group News 1: 9–11.

- 1 2 Barnett, R., Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation" (PDF). Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-24.

- 1 2 3 Haas, S.K.; Hayssen, V.; Krausman, P.R. (2005). "Panthera leo" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 762: 1–11. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)762[0001:PL]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Maas, P.H.J. 2006. Cape lion – Panthera leo melanochaitus. The Extinction Website. Downloaded on 2 July 2006.

- ↑ West P.M.; Packer C. (2002). "Sexual Selection, Temperature, and the Lion's Mane". Science. 297 (5585): 1339–43. doi:10.1126/science.1073257. PMID 12193785.

- ↑ "Kalahari xeric savanna". Worldwildife.org. 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- 1 2 3 "The Extinction Website – Species Info – Cape Lion". Petermaas.nl. 15 November 2005. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ↑ "Lion against tiger". Gettysburg Compiler. 7 February 1899. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- ↑ Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Sterling Pub Co Inc (1983), ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ↑ "African Lion". The Big Zoo.

- 1 2 Jardine, W. (1834). The Naturalist's Library. Mammalia Vol. II: the Natural History of Felinae. W. H. Lizars, Edinburgh.

- ↑ Geptner, V. G., Sludskij, A. A. (1972). Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Vysšaia Škola, Moskva. (In Russian; English translation: Heptner, V.G., Sludskii, A. A., Komarov, A., Komorov, N.; Hoffmann, R. S. (1992). Mammals of the Soviet Union. Vol III: Carnivores (Feloidea). Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, Washington DC).

- ↑ Pease, A. E. (1913). The Book of the Lion John Murray, London.

- ↑ The stuffed lion from the Museum of Emil Holub in Holice was, in 2009, identified as Cape lion (there were only six other exemplars preserved worldwide until then). Holub wrote about the lion in his diaries. News about the Holub's lion in Czech language.

- 1 2 'Extinct' lions (Cape lion) surface in Siberia. BBC News (2000-11-05). Retrieved on 2012-12-31.

- ↑ "Лев". Sibzoo.narod.ru. Archived from the original on March 29, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ↑ "South Africa: Lion Cubs Thought to Be Cape Lions". AP Archive. 8 November 2000. (with 2-minute video of cubs at zoo with John Spence, 3 sound-bites, and 15 photos)

- ↑ Rebecca Davis (4 June 2012). "We lost a zoo: Western Cape's only zoo closes". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera leo melanochaita. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Panthera leo melanochaita |

- The Extinction Website – Cape Lion – Panthera leo melanochaitus

- The Cape Lions of the Museum Wiesbaden, Germany