Carl Schurz

| Carl Schurz | |

|---|---|

| |

| 13th United States Secretary of the Interior | |

|

In office March 12, 1877 – March 7, 1881 | |

| President |

Rutherford B. Hayes James A. Garfield |

| Preceded by | Zachariah Chandler |

| Succeeded by | Samuel J. Kirkwood |

| United States Senator from Missouri | |

|

In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | John B. Henderson |

| Succeeded by | Francis M. Cockrell |

| United States Ambassador to Spain | |

|

In office July 13, 1861 – December 18, 1861 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | William Preston |

| Succeeded by | Gustav Körner |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Carl Christian Schurz March 2, 1829 Liblar, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died |

May 14, 1906 (aged 77) New York City, New York |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Margarethe Meyer |

| Alma mater | University of Bonn |

| Profession |

Politician Lawyer Journalist |

| Religion | Catholic |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

Forty-Eighters United States of America |

| Service/branch |

United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service |

1848 1862–1865 |

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars |

Revolutions of 1848 American Civil War |

Carl Christian Schurz (German: [ˈkaʁl ˈʃʊʁts]; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary, American statesman and reformer, U.S. Minister to Spain, Union Army General in the American Civil War, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of the Interior. He was also an accomplished journalist, newspaper editor and orator, who in 1869 became the first German-born American elected to the United States Senate.[1]

Early life

Carl Christian Schurz was born on March 2, 1829 in Liblar (now part of Erftstadt), in Rhenish Prussia, the son of Marianne (née Jussen), a public speaker and journalist, and Christian Schurz, a schoolteacher.[2] He studied at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne, and learned piano under private instructors. Financial problems in his family obligated him to leave school a year early, without graduating. Later he graduated from the gymnasium by passing a special examination and then entered the University of Bonn.[3]

Revolution of 1848

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors, Gottfried Kinkel. He joined the nationalistic Studentenverbindung Burschenschaft Franconia at Bonn, which at the time included among its members Friedrich von Spielhagen, Johannes Overbeck, Julius Schmidt, Carl Otto Weber, Ludwig Meyer and Adolf Strodtmann.[4][5] In response to the early events of the revolutions of 1848, Schurz and Kinkel founded the Bonner Zeitung, a paper advocating democratic reforms. At first Kinkel was the editor and Schurz a regular contributor.

These roles were reversed when Kinkel left for Berlin to become a member of the Prussian Constitutional Convention.[6] When the Frankfurt rump parliament called for people to take up arms in defense of the new German constitution, Schurz, Kinkel, and others from the University of Bonn community did so. During this struggle, Schurz became acquainted with Franz Sigel, Alexander Schimmelfennig, Fritz Anneke, Friedrich Beust, Ludwig Blenker and others, many of whom he would meet again in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War.

During the 1849 military campaign in Palatinate and Baden, he joined the revolutionary army, fighting in several battles against the Prussian Army.[3] Schurz was adjunct officer of the commander of the artillery, Fritz Anneke, who was accompanied on the campaign by his wife, Mathilde Franziska Anneke. The Annekes would later move to the U.S., where each became Republican Party supporters. Anneke's brother, Emil Anneke, was a founder of the Republican party in Michigan.[7] Fritz Anneke achieved the rank of colonel and became the commanding officer of the 34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War; Mathilde Anneke contributed to both the abolitionist and suffrage movements of the United States.

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to Zürich. In 1850, he returned secretly to Prussia, rescued Kinkel from prison at Spandau and helped him to escape to Edinburgh, Scotland.[3] Schurz then went to Paris, but the police forced him to leave France on the eve of the coup d'état of 1851, and he migrated to London. Remaining there until August 1852, he made his living by teaching the German language.

Emigration to America

While in London, Schurz married fellow revolutionary Johannes Ronge's sister-in-law, Margarethe Meyer, in July 1852 and then, like many other Forty-Eighters, emigrated to the United States.[3] Living initially in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Schurzes moved to Watertown, Wisconsin, where Carl nurtured his interests in politics and Margarethe began her seminal work in early childhood education.

In Wisconsin, Schurz soon became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the Republican Party. In 1857, he was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for lieutenant-governor. In the Illinois campaign of the next year between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln—mostly in German—which raised Lincoln's popularity among German-American voters (though it should be remembered that Senators were not directly elected in 1858, the election being decided by the Illinois General Assembly).

In 1858, he was admitted to the Wisconsin bar and began to practice law in Milwaukee. In the state campaign of 1859, he made a speech attacking the Fugitive Slave Law, arguing for states' rights. In Faneuil Hall, Boston, on April 18, 1859,[8] he delivered an oration on "True Americanism," which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of "nativism". Wisconsin Germans unsuccessfully urged his nomination for governor in 1859. In the 1860 Republican National Convention, Schurz was spokesman of the delegation from Wisconsin, which voted for William H. Seward; despite this, Schurz was on the committee which brought Lincoln the news of his nomination.

In spite of Seward's objection, grounded on Schurz's European record as a revolutionary, after his election President Lincoln sent him in 1861 as ambassador to Spain,[9] where he succeeded in quietly dissuading Spain from supporting the South.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Schurz served with distinction as a general in the Union Army. Persuading Lincoln to grant him a commission in the Union army, Schurz was commissioned brigadier general of Union volunteers in April 1862. In June, he took command of a division, first under John C. Frémont, and then in Franz Sigel's corps, with which he took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. He was promoted major general in 1863 and was assigned to lead a division in the XI Corps at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, both under General Oliver O. Howard. A bitter controversy began brewing between Schurz and Howard over the strategy employed at Chancellorsville, resulting in the routing of the XI Corps by the Confederate corps led by Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Two months later, the XI Corps again broke during the first day of Gettysburg. Containing several German-American units, the XI Corps performance during both battles was heavily criticized by the press, fueling anti-immigrant sentiments.

Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker, John Patterson Rea, and Luther Morris Buchwalter, brother to Morris Lyon Buchwalter. Senator Charles Sumner (R-MA) was a Congressional observer during the Chattanooga Campaign. Later, he was put in command of a Corps of Instruction at Nashville. He briefly returned to active service, where in the last months of the war when he was with Sherman's army in North Carolina as chief of staff of Henry Slocum's Army of Georgia. He resigned from the army after the war ended in April 1865.

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Schurz through the South to study conditions; they then quarrelled because Schurz supported General H.W. Slocum's order forbidding the organization of militia in Mississippi. Schurz's report, suggesting the readmission of the states with complete rights and the investigation of the need of further legislation by a Congressional committee, was ignored by the President.

Newspaper career

In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit, where he was chief editor of the Detroit Post. The following year, he moved to St. Louis, becoming editor and joint proprietor with Emil Preetorius of the German-language Westliche Post (Western Post), where he hired Joseph Pulitzer as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867-1868, he traveled in Germany – the account of his interview with Otto von Bismarck is one of the most interesting chapters of his Reminiscences. He spoke against "repudiation" (of war debts) and for "honest money" (the gold standard) during the Presidential campaign of 1868.

U.S. Senator

In 1868, he was elected to the United States Senate from Missouri, becoming the first German American in that body. He earned a reputation for his speeches, which advocated fiscal responsibility, anti-imperialism, and integrity in government. During this period, he broke with the Grant administration, starting the Liberal Republican movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected B. Gratz Brown governor.

After Fessenden's death, Schurz was a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs where Schurz opposed Grant's Southern policy as well as his bid to annex Santo Domingo. Schurz was identified with the committee's investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1869, he became the first U.S. Senator to offer a Civil Service Reform bill to Congress. During Reconstruction, Schurz was opposed to federal military enforcement and protection of African American civil rights, and held nineteenth century ideas of European superiority and fears of miscegenation.[10][11]

In 1870, Schurz formed the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed President Ulysses S. Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo, and his use of the military to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in the South under the Enforcement Acts. Schurz lost the 1874 Senatorial election to Democratic Party challenger and former Confederate, Francis Cockrell. After leaving office, he worked as an editor for various newspapers. In 1877, Schurz was appointed Secretary of Interior by President Rutherford B. Hayes. Although Schurz honestly attempted to reduce the effects of racism toward Native Americans and was partially successful at cleaning up corruption, his solutions towards American Indians "in light of late twentieth-century developments", were repressive.[12] Indians were forced to move into low quality reservation lands that were unsuitable for tribal economic and cultural advancement.[12] Promises made to Indian chiefs at White House meetings with President Rutherford B. Hayes and Schurz were not always kept.[12]

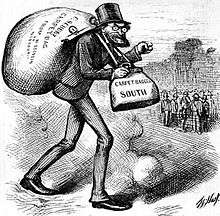

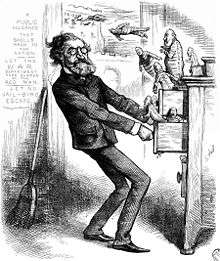

In 1872, he presided over the Liberal Republican Party convention, which nominated Horace Greeley for President. Schurz's own choice was Charles Francis Adams or Lyman Trumbull, and the convention did not represent Schurz's views on the tariff. Schurz campaigned for Greeley anyway. Especially in this campaign, and throughout his career as a Senator and afterwards, he was a target for the pen of Harper's Weekly artist Thomas Nast, usually in an unfavorable way.[13] The election was a debacle for the Greeley supporters: Grant won by a landslide, and Greeley died shortly after the election.

In 1875, he campaigned for Rutherford B. Hayes, as the representative of sound money, in the Ohio governor's campaign.

Secretary of the Interior

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him Secretary of the Interior, following much of his advice in other cabinet appointments and in his inaugural address. In this department, Schurz put in force his theories in regard to merit in the Civil Service, permitting no removals except for cause, and requiring competitive examinations for candidates for clerkships. His efforts to remove political patronage met with only limited success, however. As an early conservationist, he prosecuted land thieves and attracted public attention to the necessity of forest preservation.

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, there was a movement, strongly supported by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the War Department.[14] Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its "pacification" program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department. The Indian Office had been the most corrupt of the Interior Department. Positions therein were based on political patronage and were seen as granting license to use the reservations for personal enrichment. Schurz realized that the service would have to be cleansed of such corruption before anything positive could be accomplished, so he instituted a wide-scale inspection of the service, dismissed several officials, and began civil service reforms, whereby positions and promotions were to be based on merit not political patronage.[15]

Schurz's leadership of the Indian Affairs Office was not uncontroversial. While certainly not an architect of the campaign to push Native Americans off their lands and into tribal reservations, he continued the practice of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of resettling tribes on reservations. In response to several nineteenth-century reformers, however, he later changed his mind and promoted an assimilationist policy.[16][17]

Later life

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to New York City. That year German-born Henry Villard, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, acquired the New York Evening Post and The Nation and turned the management over to Schurz, Horace White and Edwin L. Godkin.[19] Schurz left the Post in the autumn of 1883 because of differences over editorial policies regarding corporations and their employees.[20]

In 1884, he was a leader in the Independent (or Mugwump) movement against the nomination of James Blaine for president and for the election of Grover Cleveland. From 1888 to 1892, he was general American representative of the Hamburg American Steamship Company. In 1892, he succeeded George William Curtis as president of the National Civil Service Reform League and held this office until 1901. He also succeeded Curtis as editorial writer for Harper's Weekly in 1892 and held this position until 1898. In 1895 he spoke for the Fusion anti-Tammany Hall ticket in New York City. He opposed William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896, speaking for sound money and not under the auspices of the Republican party; he supported Bryan four years later because of anti-imperialism beliefs, which also led to his membership in the American Anti-Imperialist League.

True to his anti-imperialist convictions, Schurz exhorted McKinley to resist the urge to annex land following the Spanish–American War.[21] In the 1904 election he supported Alton B. Parker, the Democratic candidate. Carl Schurz lived in a summer cottage in Northwest Bay on Lake George, New York which was built by his good friend Abraham Jacobi.

Death and legacy

Schurz died at age 77 on May 14, 1906 in New York City and is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Sleepy Hollow, New York.[22]

Schurz's wife, Margarethe Schurz, was instrumental in establishing the kindergarten system in the United States.[23] Schurz is famous for saying: "My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right."[24]

Works

Schurz published a number of writings, including a volume of speeches (1865), a two-volume biography of Henry Clay (1887), essays on Abraham Lincoln (1899) and Charles Sumner (posthumous, 1951), and his Reminiscences (posthumous, 1907–09). His later years were spent writing the memoirs recorded in his Reminiscences which he was not able to finish — he only reached the beginnings of his U.S. Senate career. Schurz was a member of the Literary Society of Washington from 1879 to 1880.[25]

Memorials

Schurz is commemorated in numerous places around the United States:

- Carl Schurz Park, a 14.9 acre (60,000 m²) park in New York City, adjacent to Yorkville, Manhattan, overlooking the waters of Hell Gate. Named for Schurz in 1910, it is the site of Gracie Mansion, the residence of the Mayor of New York since 1942

- Karl Bitter's 1913 monument to Schurz outside Morningside Park, at Morningside Drive and 116th Street in New York City

- Carl Schurz and Abraham Jacobi Memorial Park in Bolton Landing, New York

- Schurz, Nevada named after him

- Carl Schurz Drive, a residential street in the northern end of his former home of Watertown, Wisconsin

- Schurz Elementary School, in Watertown, Wisconsin

- Carl Schurz Park, a private membership park in Stone Bank (Town of Merton), Wisconsin, on the shore of Moose Lake

- Carl Schurz Forest, a forested section of the Ice Age Trail near Monches, Wisconsin

- Schurz Monument ("Our Greatest German American") in Menominee Park, Oshkosh, Wisconsin[26]

- Carl Schurz High School, a historic landmark in Chicago, built in 1910.

- Schurz Hall, a student residence at the University of Missouri.

- Carl Schurz Elementary School in New Braunfels, Texas

- Mount Schurz, a mountain in eastern Yellowstone, north of Eagle Peak and south of Atkins Peak, named in 1885 by the United States Geological Survey, to honor Schurz's commitment to protecting Yellowstone National Park

- In 1983, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 4-cent Great Americans series postage stamp with his name and portrait

- In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Carl Schurz was named in his honor.

- The USS Schurz was commissioned in 1917 as a Patrol Gun Boat. Formerly the small unprotected cruiser SMS Geier of the German Imperial Navy, the ship had been taken over by the U.S. Navy when hostilities between Germany and the U.S. commenced, after having been interned in Honolulu in 1914. The Schurz sank after a collision on 21 June 1918 off Beaufort Inlet, Florida.

Several memorials in Germany also commemorate the life and work of Schurz, including:

- Streets named after him in Berlin-Spandau, Bremen, Stuttgart, Erftstadt-Liblar, Giessen, Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, Köln, Neuss, Rastatt, Paderborn, Pforzheim, Pirmasens, Leipzig, Wuppertal

- Schools in Bonn, Bremen, Berlin-Spandau, Frankfurt am Main, Rastatt and his place of birth, Erftstadt-Liblar

- The Carl-Schurz-Haus Freiburg, in Freiburg im Breisgau is an innovative institute (formerly Amerika-Haus) fostering German-American cultural relations

- an urban area in Frankfurt am Main

- the Carl Schurz Bridge over the Neckar River[27]

- a memorial fountain as well as the house where Lt. Schurz was billeted in 1849 in Rastatt

- German Armed Forces barracks in Hardheim

- German federal stamps in 1952 and 1976

Harper's Weekly gallery

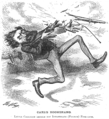

Schurz and other anti-Grant "conspirators" – March 16, 1872

Schurz and other anti-Grant "conspirators" – March 16, 1872 French Arms investigation – May 11, 1872

French Arms investigation – May 11, 1872 Schurz and his victims – September 7, 1872

Schurz and his victims – September 7, 1872 Schurz is depicted as a carpetbagger - November 9, 1872.

Schurz is depicted as a carpetbagger - November 9, 1872. Schurz leaves the U.S. Senate – March 20, 1875

Schurz leaves the U.S. Senate – March 20, 1875 Schurz reforms the Indian Bureau – January 26, 1878

Schurz reforms the Indian Bureau – January 26, 1878 Schurz counsels a wounded settler – December 28, 1878

Schurz counsels a wounded settler – December 28, 1878 Schurz and Wilhelm II – July 14, 1900

Schurz and Wilhelm II – July 14, 1900 Schurz and Emilio Aguinaldo – August 9, 1902

Schurz and Emilio Aguinaldo – August 9, 1902 - February 26, 1881

- February 26, 1881

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- Forty-Eighters

- German Americans in the Civil War

- German American

- German-American Heritage Foundation of the USA

-

Letter from Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, November 8, 1862.

Letter from Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, November 8, 1862.

Notes

- ↑ "404 Error: File Not Found - Wisconsin Historical Society". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Greasley, Philip A. (30 May 2001). "Dictionary of Midwestern Literature, Volume 1: The Authors". Indiana University Press. Retrieved 2 November 2016 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 Dictionary Of American Biography (1935), Carl Schurz, p. 466.

- ↑ Schurz, Carl. Reminiscences, Vol. 1, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Van Cleve, Charles L. (1902). Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity From Its Foundation In 1852 To Its Fiftieth Anniversary. p. 209: Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company.

- ↑ Schurz, Reminiscences, Vol. 1, Chap. 6, pp. 159.

- ↑ W. R. Mc Cormick: BAY COUNTY Memorial Report: Emil Anneke: in: Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan, Vol. XIV, 1890, Lansing, Michigan, W. S. George & Co., State Printers & Binders, Page 57–58

- ↑ Hirschhorn, p. 1713.

- ↑ Dictionary Of American Biography (1935), Carl Schurz, p. 467

- ↑ Mejías-López (2009), The Inverted Conquest, p. 132.

- ↑ Brands (2012), The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace, p. 489.

- 1 2 3 Fishel-Spragens (1988), Popular Images of American Presidents, p. 121

- ↑ This story, and the conflict between Nast and Harper's editorial writer George William Curtis, is related by Albert Bigelow Paine in Thomas Nast: His Period and His Pictures, 1904.

- ↑ "Army charges answered". The New York Times: 5. December 7, 1878.

ARMY CHARGES ANSWERED; THE INDIAN SERVICE UPHELD BY MR. SCHURZ. WHY IT WOULD BE UNWISE TO TRANSFER THE INDIAN BUREAU TO THE WAR DEPARTMENT--INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY MILITARY OFFICERS--LOOSE MANAGEMENT UNDER THE ARMY. INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY ARMY OFFICERS. ALLEGED ARMY DISHONESTY. MEASURES OF IMPORTANCE. MR. SCHURZ CROSS-EXAMINED. OTHER WITNESSES

- ↑ Trefousse, Hans L., Carl Schurz: A Biography, (U. of Tenn. Press, 1982)

- ↑ Hoxie, Frederick E. A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

- ↑ "Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, November 1, 1880," In Prucha, Francis Paul, ed., Documents of United States Indian Policy, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. See Google Books.

- ↑ Sturm und Drang Over a Memorial to Heinrich Heine. The New York Times, May 27, 2007.

- ↑ Villard, Oswald Garrison (1936). "White, Horace". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ↑ "No Longer an Editor; Carl Schurz Severs his Connection with the 'Evening Post'." The New York Times, December 11, 1883

- ↑ Tucker (1998), p. 114.

- ↑ Carl Schurz at Find a Grave

- ↑ "404 Error: File Not Found - Wisconsin Historical Society". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Schurz, Carl, remarks in the Senate, February 29, 1872, The Congressional Globe, vol. 45, p. 1287. See Wikisource for the complete speech.

- ↑ Spauling, Thomas M. (1947). The Literary Society in Peace and War. Washington, D.C.: George Banta Publishing Company.

- ↑ "Schurz Monument - Postcard - Wisconsin Historical Society". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "Schurz Bridge". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

References

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Schurz, Carl". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Schurz, Carl". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Tucker, David M. (1998). Mugwumps: public moralists of the gilded age. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1187-9.

- Yockelson, Mitchell, "Hirschhorn", Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

Further reading

- Schurz, Carl. The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz (three volumes), New York: McClure Publ. Co., 1907–08. Schurz covered the years 1829–1870 in his Reminiscences. He died in the midst of writing them. The third volume is rounded out with A Sketch of Carl Schurz's Political Career 1869–1906 by Frederic Bancroft and William A. Dunning. Portions of these Reminiscences were serialized in McClure's Magazine about the time the books were published and included illustrations not found in the books.

- Bancroft, Frederic, ed. Speeches, Correspondence, and Political Papers of Carl Schurz (six volumes), New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1913.

- Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1971

- Donner, Barbara. "Carl Schurz as Office Seeker," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 20, no.2 (December 1936), pp. 127–142.

- Donner, Barbara. "Carl Schurz the Diplomat," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 20, no. 3 (March 1937), pp. 291–309.

- Fish, Carl Russell. "Carl Schurz-The American," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 12, no. 4 (June 1929), pp. 346–368.

- Fuess, Claude M. Carl Schurz, Reformer, (NY, Dodd Mead, 1932)

- Nagel, Daniel. Von republikanischen Deutschen zu deutsch-amerikanischen Republikanern. Ein Beitrag zum Identitätswandel der deutschen Achtundvierziger in den Vereinigten Staaten 1850-1861. Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2012.

- Schafer, Joseph. "Carl Schurz, Immigrant Statesman," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 11, no. 4 (June 1928), pp. 373–394.

- Schurz, Carl. Intimate Letters of Carl Schurz 1841-1869, Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1928.

- Trefousse, Hans L. Carl Schurz: A Biography, (1st ed. Knoxville: U. of Tenn. Press, 1982; 2nd ed. New York: Fordham University Press, 1998)

- Twain, Mark, "Carl Schurz, Pilot," Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1906.

External links

- United States Congress. "Carl Schurz (id: S000151)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-08-12

- Works by Carl Schurz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl Schurz at Internet Archive

- Works of Carl Schurz, compiled by Bob Burkhardt.

-

The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz at Wikisource.

The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz at Wikisource. -

Twain, Mark. Carl Schurz, Pilot, Harper's Weekly, May 26, 1906, p. 727.

Twain, Mark. Carl Schurz, Pilot, Harper's Weekly, May 26, 1906, p. 727. - Reynolds, Robert L. "A Man of Conscience", American Heritage Magazine, vol. 14, no. 2 (1963).

- "Schurz: The True Americanism" Harper's Magazine, November 1, 2008.

- "Carl Schurz" from Charles Rounds, Wisconsin Authors and Their Works, 1918.

- The Political Graveyard

- Abraham Lincoln's White House - Carl Schurz

- The Carl Schurz Papers, containing materials especially of interest to the examination of Schurz's image in the press and in the German-American community, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- WMF project links

-

Quotations related to Carl Schurz at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Carl Schurz at Wikiquote -

Media related to Carl Schurz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carl Schurz at Wikimedia Commons -

Works related to Carl Schurz at Wikisource

Works related to Carl Schurz at Wikisource -

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Carl Schurz

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Carl Schurz

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Preston |

U.S. Minister to Spain 1861 |

Succeeded by Gustavus Koerner |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by John B. Henderson |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Missouri 1869–1875 Served alongside: Charles D. Drake, Daniel T. Jewett, Francis P. Blair, Jr., Lewis V. Bogy |

Succeeded by Francis M. Cockrell |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Zachariah Chandler |

U.S. Secretary of the Interior Served under: Rutherford B. Hayes 1877–1881 |

Succeeded by Samuel J. Kirkwood |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by John Sedgwick |

Commander of the XI Corps (ACW) January 19, 1863 – February 5, 1863 |

Succeeded by Franz Sigel |

| Preceded by Adolph von Steinwehr |

Commander of the XI Corps (ACW) March 5, 1863 – April 2, 1863 |

Succeeded by Oliver O. Howard |