Carlos Brewer

| Carlos Brewer | |

|---|---|

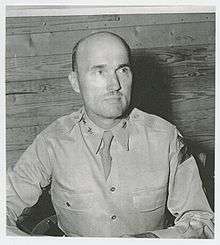

Major Gen. Carlos Brewer (c. 1943–1944) | |

| Born |

5 December 1890 Golo, Kentucky |

| Died |

29 September 1976 (aged 85) Columbus, Ohio |

| Place of burial | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1913–1950 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | Field Artillery Branch |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

Legion of Merit Bronze Star |

Carlos Brewer (5 December 1890 – 29 September 1976) was a United States Army Major General who commanded the 6th Armored Division (United States) and the 12th Armored Division (United States) during World War II. After training the 12th Armored Division, he was not permitted to command the division in combat due to his age, so he requested his rank be reverted from Major General to Colonel so that he could become an artillery officer in the European Theater of Operations.[1][2] He innovated the method of field artillery targeting used in World War II, and implemented triangular organization of divisions.

Early life

Carlos Brewer was born on 5 December 1890 in Golo, Kentucky[3] and attended West Kentucky College in Mayfield, Kentucky, until he entered United States Military Academy at West Point in 1909, graduating 15th in his class in 1913.[4] Many of the graduates of the West Point Class of 1913 later became general officers, including Alexander Patch, Douglass T. Greene, Geoffrey Keyes, Willis D. Crittenberger, Charles H. Corlett, Paul Newgarden, William R. Schmidt, Robert L. Spragins, Louis A. Craig, Selby H. Frank, Henry B. Lewis, John E. McMahon, Jr., Richard U. Nicholas, Robert H. Van Volkenburgh, Robert M. Perkins, William A. McCulloch, Francis K. Newcomer, Lunsford E. Oliver and Henry B. Cheadle.

After graduation, Brewer went onto the Field Artillery branch of service.[5]

Military career

Upon graduation from West Point in 1913, Brewer was commissioned as a Second lieutenant and was assigned to the 3rd Field Artillery at Fort Sam Houston, serving along the Texas border until 1916 during the Mexican Revolution. In March 1916, he went with the 4th Field Artillery to the Panama Canal Zone. From August 1916 through 1921, he taught in the Department of Mathematics at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.[2][5] In 1920, he was promoted to Major.[6] From 1921 through 1924, he went to the 8th Field Artillery in Hawaii.[5]

Brewer studied at the Advanced Course at the Field Artillery School at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, in 1926–1927, and then graduated at the top of his class at the Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth (1927–1928). He went back to the Field Artillery School in 1928 and taught in the Gunnery Department, becoming the Director of the department.[4][5] His immediate predecessor as head of the Department of Gunnery, who was also an instructor when Brewer took advanced coursework there, was Jacob Devers, who would remain a lifelong friend and later prove providential in the course of his career.

The Artillery School's most innovative work came with the creation of the fire direction center during the 1930s under the leadership of its Director of Gunnery, Carlos Brewer and his instructors, who abandoned massing fire by a described terrain feature or grid coordinate reference. They introduced a firing chart, adopted the practice of locating battery positions by survey, and designated targets with reference to the base point on the chart. In the spring of 1931, the Gunnery Department successfully demonstrated massing battalion fire using this method.[7]

"During his period as Director of the Department of Gunnery, [Brewer] developed the technique of fire direction with a central fire direction center in the battalion which proved very effective in World War II. This procedure permitted the massing of fire of all the divisional artillery on a target that one battery had adjusted on, or on a target that the division commander had designated, in a matter of minutes. One big advantage of this central fire control is that a few specialists can perform the necessary technical operations for the entire battalion. As a result of this development, the division commanders were generally well pleased with the artillery support in World War II."[5]

Brewer graduated from the Army War College in 1934 with a superior rating. While his wife was convalescing due to tuberculosis, he became head of the Military Science Department of the ROTC Program at Purdue University, the largest field artillery unit in the Army at the time. In 1939, he was assigned to command the 25th Field Artillery Battalion at Madison Barracks, NY. In 1941, he was then transferred to Fort Benning, GA to command the 7th Field Artillery Regiment, where he developed the triangular division organization that was adopted during World War II. After 2 months of courses at the Naval War College, he served as Assistant, then Chief of Staff (G-3) for the newly activated 9th Infantry Division, now commanded by his mentor Gen. Jacob Devers at Fort Bragg, NC from August 1940 to Feb. 1942. In June 1941, he was promoted to Colonel[5][6] Brewer planned and implemented the triangular division organization for the 9th Infantry Division consisting of 3 infantry regiments and 4 artillery battalions, constituting 9,000 soldiers, with an additional 5,000 draftees completing the ranks, beginning in 1941.[8]

On 16 Feb 1942, Brewer was promoted to Brigadier General and given command of the 6th Armored Division.[6] On 7 August 1942, he was promoted to Major General, and assumed command of the new 12th Armored Division on 19 August 1942, which was activated at Camp Campbell, Kentucky, on 2 September 1942. He oversaw their training through the Tennessee Maneuvers, from September into November 1943 and re-organization from a heavy to a medium tank division. He continued to supervise the training of the 12th Armored Division at Camp Barkeley, near Abilene, Texas, from November, 1943, until August 1944 when the Division prepared to depart for the European Theater of Operations.[1]

Despite the 12th Armored Division receiving excellent ratings in its final evaluation of readiness for combat service, Brewer was relieved of command and assigned to training replacement troops at Camp Wheeler, Georgia.[1][5][6] U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall informed Brewer that Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) General Dwight D. Eisenhower had requested that only commanders of Divisions younger than 50 years old be sent to command soldiers in the European Theater of Operations, and Brewer was 54 years old at the time.[1] Brewer was replaced as Commanding General of the 12th Armored Division by Douglass T. Greene, who had been in his 1913 graduating class at West Point.[9]

World War II combat

Brewer had missed combat duty during World War I because he had been on the faculty teaching at West Point and was not enamored with having a non-combat command again. He requested termination of his rank of Major General and permanent reversion to the rank of Colonel, [1][2] then he wrote to Gen. Jacob Devers who had been his instructor at Field Artillery School, whom he replaced as its director, and for whom he served as Chief of Staff with the 9th Infantry Division. Devers was in command of the newly formed Sixth United States Army Group leading the Allied invasion in the south of France, which consisted of the 7th Army under Gen. Alexander Patch and the First French Army under Gen. Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. His former command, the 12th Armored Division was assigned to the 7th Army. Brewer asked Devers if as a Colonel he could command the newly formed 46th Group Heavy Army Artillery assigned to the 7th Army, commanded by Patch who had been in the same graduating class at West Point and with whom he served under Jacob Devers with the 9th Infantry Division.[8] The 46th Field Artillery Group under Col. Brewer began its combat operations in January 1945 in the Vosges Mountains, providing heavy artillery support for the VI Corps, commanded by Major General Edward H. Brooks. They continued support of the Corps through its advance into Germany through the Siegfried Line, across the Rhine river, through the Black Forest and into Bavaria. Their combat ended at Garmisch when the Germans surrendered on 8 May 1945.

Post-World War II

Brewer served in the Army of Occupation under the command of General Geoffrey Keyes as the Seventh Army Artillery Officer and as Headquarters Commandant & Commander of the Heidelberg Area Command in Germany from 1946–47.[2][4] From 1947–50, he was Professor of Military Science & Tactics at Ohio State University where he ran the ROTC Program. He retired from the military in 1950, but continued working for the Ohio State Research Foundation from 1950 – 1960 as a consultant on classified military research contracts.[3][5]

Personal life

He married Grace Moore (1891–1956) on 20 December 1913. They had four children: Carlos Jr., Edward, Robert, and Grace Elizabeth Brewer Schulten.[3][10] After the death of his first wife from tuberculosis in 1956, he married Mary Taylor Williams in 1959.[5]

At West Point, he was on the polo team, was an expert marksman, and was on the broadsword team.[11]

He also was an avid chess player, and was one of twenty players at West Point who played simultaneous games against nine-year old Polish chess prodigy Samuel Reshevsky in 1920. Reshevsky won 19 of the 20 games, including the game against Brewer, which lasted just under two hours.[12]

Awards

Major General Brewer´s ribbon bar[4][13]

See also

- 12th Armored Division (United States)

- 6th Armored Division (United States)

- Sixth United States Army Group

- 7th Army (United States)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradstreet, Ken (1987). 12th Armored Division History Book Vol. 1 (PDF). Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company. p. 11. ISBN 0-938021-09-5. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Carlos Bruo'er Brewer, Major General, United States Army". Arlington National Cemetery Website. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Brewer, Ted. "Memorial Service for Maj. Gen Carlos Brewer" (Vol. 31, No. 3, Ed. 1). (Kirkland, Wash.): Hellcat News. p. 5. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullum, George Washington (1940). Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from its establishment, in 1802 : [Supplement, volume VIII 1930–1940. R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company, The Lakeside Press Chicago, Illinois, and Crawfodsville, Indiana. p. 261.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Carlos Brewer 1913". West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Generals of WWII – Brewer, Carlos". Generals.dk. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Dastrup, Boyd (January 2011). "History of the US Army Field Artillery School from birth to the eve of World War II: Part I of II" (PDF). Fires. A Joint Publication for U.S. Artillery Professionals: 7–11. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 Wheeler, James Scott (21 September 2015). Jacob L. Devers: A General's Life. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-8131-6603-2.

- ↑ "Douglass T. Greene 1913". West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "MG Carlos Brewer". Find A Grave. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ "Major General Carlos Brewer". Hellcat News (Vol. 33, No. 1). Springfield, Ill. The Portal to Texas History. September 1978. p. 18. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Hartwig Cassell; Hermann Helms (1920). American Chess Bulletin. H. Cassell and H. Helms. pp. 169–.

- ↑ "Brewer, Carlos, MG". Together We Served. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

External links

- Brewer, Carlos "Flash-Sound Ranging" The Field Artillery Journal, vol. XXI, no. 4: 345–53, July – August 1931

- Brewer, Carlos "Recommendations for Changes in Gunnery Instruction and Battalion Organization," June 2, 1932, Field Artillery School Archives, Morris Swett Technical Library, Fort Sill, Oklahoma, 1.316

- Calhoun, Mark T. "General Lesley J. McNair: Little-Known Architect of the U.S. Army" Ph.D. Dissertation, Dept. of History, University of Kansas, 2012

- Walker, John R. "Bracketing the Enemy: Forward Observers and Combined Arms Effectiveness During The Second World War" Ph.D. Dissertation, Kent State University, August 2009, p. 67 et. seq.