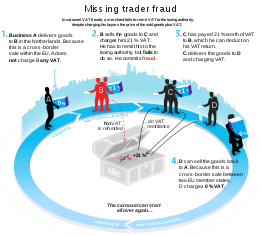

Missing trader fraud

Missing trader fraud (also called missing trader intra-community, MTIC, or carousel fraud) is the theft of Value Added Tax (VAT) from a government by organised crime gangs who exploit the way VAT is treated within multi-jurisdictional trading where the movement of goods between jurisdictions is VAT-free. This allows the fraudster (person who commits fraud) to charge VAT on the sale of goods, and then instead of paying this over to the government's collection authority, to simply abscond, taking the VAT with him. The term "missing trader" refers to the fact that the trader goes missing with the VAT. "Carousel" refers to a more complex type of fraud in which VAT and goods are passed around between companies and jurisdictions, similar to how a carousel goes round and round.

European Union

In the European Union (EU) the European Union Value Added Tax ("EU VAT") allows merchants to charge VAT on the sale of goods when they sell goods to another member state.

Figures released in September 2006 by Eurocanet, a project sponsored by the European Commission, appear to show that the United Kingdom is the main victim of this fraud – the UK lost an estimated €12.6 billion during 2005–6 – followed by Spain and Italy, which each lost over €2 billion.[1] From 1 June 2007, the UK introduced changes to the way that VAT is charged on mobile phones and computer chips to help combat fraud.[2][3] UK plans to introduce changes to the way VAT is charged on a wide range of goods from December 2006 were aborted because of failure to reach an agreement with other EU member states.

Operation of the VAT system

In brief, a business that buys and sells goods charges VAT to those to whom it sells ('output tax'), and is charged VAT by those from whom it purchases ('input tax'). It can reclaim (subject to various rules) the VAT it pays, and so passes to the Government the net VAT it collects (being output tax less input tax). In this way, a business acts as a tax collector on behalf of the Government.

Within the EU VAT, member states charge VAT at differing rates on goods as a form of indirect taxation. All exports of goods however are tax free. This leads to the situation where an exporter will be able to reclaim VAT from the Government, as it will have been charged VAT by the business from which it purchased the goods, and will owe the Government nothing because it has sold the goods tax free.

Operation of the fraud

The fraud exploits this reclamation of tax. It lends itself to small, high value items, such as microchips and mobile telephones.

Missing trader fraud

The simplest missing trader fraud is where a fraudster imports some goods. The goods were zero-rated in the country of origin, and VAT on the goods should be paid in the country where they have been imported. However, the fraudster charges a buyer the price of the goods plus VAT, but doesn't pass on the VAT to the Government. He becomes a "missing trader". Because the goods were zero-rated for export, the Government has lost the entire VAT that should be paid on the goods, rather than the fraction of it that would be paid for just one stage of the production process. This situation, where the goods are made available for consumers in the importer's home market is often known as 'acquisition fraud'.

Carousel fraud

The imported goods may be sold from one trader to another, and eventually exported. When this happens, the exporter can claim back from the government the whole of the VAT that should have been paid on the goods (as exports are zero-rated). However, if there is a "missing trader" further back in the chain of sales, part of this VAT was never paid in the first place. Hence, there is a loss to the government.

This can repeat many times, with the goods going round in a 'carousel'.

Example

Consider a trader based in the UK. He buys from France a consignment of mobile telephones for £1,000,000. He pays the French telephone manufacturer for the goods. The goods are then shipped to a dock in the UK. No VAT is charged on that shipment.

The trader now sells those telephones to a conspirator, for £1,100,000. He charges 20% VAT and the conspirator sends £1,320,000 (being the price of the goods plus the tax) to the trader.

This conspirator then sells the goods to a third conspirator for £1,200,000, charging VAT on that sale. The third conspirator pays £1,440,000 to the second. This may continue for many conspirators; however, three will suffice for an example. The third trader now sells the telephones to a German company, which may well be innocent. No VAT is charged on the export, and the sales price of £1,500,000 is paid by the German company without VAT. So far the conspirators have made a profit of £500,000 perfectly legitimately on buying and selling mobile telephones. In an honest operation, the first trader would pay £220,000 to HM Revenue and Customs (the UK's VAT collection agency). The second trade has collected £240,000 in VAT but paid £220,000 in VAT and therefore has to pay only the difference (£20,000) to HM Revenue and Customs. The third trader has charged no tax on its sale but has paid £240,000 in VAT and can therefore reclaim £240,000 from HM Revenue and Customs. In the fraud, the first business vanishes without paying the VAT to HM Revenue and Customs. When the last business in the chain collects £240,000 on the export, all of the businesses can vanish, £220,000 better off at the expense of HM Revenue and Customs. As this business is removed from the vanishing party, it is difficult for HM Revenue and Customs to show the links in the chain and thereby refuse to refund the VAT on the export.

In terminology, each business described above is called a "buffer". In a real case there can be many buffers, all helping to blur the link between the final reclaim and the original importer, which will vanish. Buffer is what these companies are, but they are actually referred to as a number. A number 1 is always the importer. In addition banks are used to make 3rd party payments. These obscure banks are called "platforms" and work on the escrow principle. This means money is uploaded and transferred immediately through the client accounts and it takes a day for the money to come out of the platform. The biggest platform was First Curaçao International Bank (FCIB) which was closed by the Netherlands authorities in 2006. Using these offshore platforms means that authorities cannot trace the money until they inspect books and as the missing trader has already fled they don't get to see where the money has been routed.

This entire series of transactions can occur without the goods ever leaving the dock in the UK before being re-exported. Furthermore, the same goods can be used again and again going through the various buffers, each pass around the 'carousel' bringing reclaimed VAT to the fraudsters.

Contra-trading

Contra-trading fraud is the further evolution of carousel fraud, and evades government detection by using two carousels of traded goods where one carousel is legitimate and the other is not thereby allowing an accounting scheme where the input and output VATs neutralize each other thereby concealing the fraud.[4] Jaswant Ray Kanda, of Sutton Coldfield, West Midlands and his gang were key players in this type of carousel fraud.[5] Customs Officials who were investigating them called their operation Maypole as they had clear evidence that Kanda and his gang sent the same lot of goods round and round again.

"Innocent parties" - the 'Bond House' decision

Although the example above referred to all the links being co-conspirators in the fraud, according to a decision in the European Court of Justice it is possible that innocent parties also become involved by simply buying and selling on goods. If it is the first party in the chain who is the absconding fraudster, the goods can continue to be sold-on by innocent parties.

In the UK, the position until 2006 was that HM Customs and Excise withheld VAT repayments to others later on in the chain, on the basis that the transactions were lacking in economic substance and so should be outside the scope of the VAT regime.

Bond House Systems Limited was one such "innocent trader", who was owed £13,200,000 in VAT repayments by HM Customs and Excise. It challenged the UK Government's stance, taking the case eventually to the European Court of Justice. In January 2006 the ECJ found in favour of Bond House and ordered that the VAT owed to Bond House be repaid by HM Revenue & Customs. It is estimated the decision will cost the UK government hundreds of millions of pounds as other companies make their claims.

Cost of the fraud

According to the case Federation of Technological Industries v Customs and Excise Commissioners [2004] EWCA Civ 1020 in 2002-03 the estimated cumulative cost of such frauds to the UK alone was between £1.65 and £2.64 billion (US$2.9 to $4.62).

According to the BBC, "So-called 'missing trader' or 'carousel' fraud is estimated to cost European governments up to £170bn a year – twice the European Union's annual budget."[6]

The fraud has evolved and now can incorporate all high value goods such as designer goods, health products, jewellery etc.

References

- ↑ Oliver, James (2006-09-22). "VAT scams hit UK taxpayers hard". BBC News.

- ↑ "Clampdown on VAT fraud". BBC News. 2006-09-18.

- ↑ "New anti-fraud VAT rules come in". BBC News. 2007-03-19.

- ↑ Olympia Technologies Ltd. VAT Tribunal #20570 (2-15-08)

- ↑ "£54 million VAT fraud gang is jailed". Birmingham Mail. 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Phil Kemp (2008-10-04). "Fraudster's 'pop star' lifestyle". BBC News.

- Federation of Technological Industries v Customs and Excise Commissioners ([2004] EWCA Civ 1020)

- European Court of Justice decision EUECJ/2006/C35403

- HM Revenue & Customs PN03 2006 Budget Release

- Successful Prosecutions in £138m "Carousel" Frauds – 21 Convicted, Sentences of 202 Years

- The Fraudsters – How Con Artists Steal Your Money Chapter 7 – The Cash Carousel (ISBN 978-1-903582-82-4) by Eamon Dillon, published September 2008 by Merlin Publishing

External links

- Experts stumped by leap in trade gap, Guardian, September 10, 2005, discusses "missing trader fraud" and "carousel fraud".

- EU clampdown spawns new carousel fraud, Guardian, May 29, 2007, discusses "contra trading" in the EU and "flipping" in Canada.