Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge

The Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge was a bridge chapel built near the centre of "Old" London Bridge in the City of London and was completed by 1209. In 1548, during the Reformation, it was dissolved as a place of worship and soon afterwards converted to secular use. The building survived as a dwelling and warehouse until 1747 when the upper storey at street level was removed; the lower storey, which was built into the structure of one of the piers, remained in use as a store until Old London Bridge was demolished in 1832.

Background

Wooden bridges crossing the River Thames between Southwark and the City of London had existed at various times since the Roman occupation, but had always utilised the same site. The last wooden London Bridge was built from elm in about 1163, under the direction of Peter de Colechurch, the priest of the parish church of St Mary Colechurch in Cheapside. This came at a period of growth and prosperity for the City, and it is likely that the wooden bridge soon proved to be inadequate.[1]

Work on the foundations for the first pier of a news stone London Bridge began in 1176, also under Peter de Colechurch. The construction may have been instigated by King Henry II who levied a tax on wool, sheepskin and leather to help pay for the bridge. The eleventh pier from the Southwark side was built as the largest of the nineteen piers, specifically to accommodate a chapel dedicated to the popular saint and martyr, Thomas à Becket, who had been murdered by Henry's followers in 1170 and for whom the king had since performed extensive public penance. The building of bridge chapels was common in the high medieval period, as the construction of bridges was considered an act of religious piety.[2]

Description

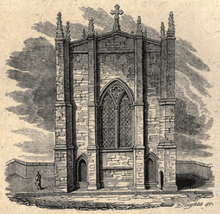

Most of our knowledge of the design of St Thomas on the Bridge comes from a survey by the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661 – 1736), made while the chapel was still standing and published in a pamphlet called A Short Historical Account of London Bridge in 1736. Based on this data, a series of engravings were made by George Vertue (1684 – 1756), giving an impression of how the building would have appeared before it was modified for secular use.[3]

The chapel was built on two levels; the Lower Chapel, variously described as a crypt or undercroft, was integral to the structure of the pier itself, which projected 65 feet (20 metres) out from the centre line of the bridge on the downstream or eastern side. The Upper Chapel was entered from the street which passed it on the upstream or western side. The building was 60 feet (18 m) long and 20 feet (6 m) wide. The plain façade, pierced by two doors and a pointed arched window divided by a single mullion, stood 40 feet (12 m) above street level. The high interior of the Upper Chapel was supported by fourteen clustered columns and lit by eight large arched windows. The Lower Chapel could be accessed either directly from the street or from the Upper Chapel via a spiral staircase; also from a door in the lower part of the pier opened onto the starling, the small artificial island on which each of the piers was built, which allowed entry by fishermen and watermen directly from the river. The Lower Chapel had a rib vaulted ceiling about 20 feet (6 m) high and was paved in black and white marble flagstones. Both chapels terminated in a three sided apse at the eastern end.[4]

History of the chapel

The Chapel of St Thomas seems to have been actually founded before 1205 with two priests or chaplains and four clerks. The chapel was burnt down in a fire on the bridge in 1212 but was rebuilt soon afterwards. The clergy of the chapel, referred to as the "Brethren of the Bridge", lived together in accommodation called the Bridge House, the location of which is uncertain, but was later on the Southwark bank and became the governing institution of London Bridge. The chapel was enriched by bequests establishing chantries for the saying of masses for the repose of the souls of the benefactors. Relics held there included what was believed to be a fragment of the True Cross. Between 1384 and 1397, the chapel was rebuilt and enlarged.

Lying within the parish of the City church of St Magnus the Martyr, there were constant disputes between the brethren, the bridge masters and the parish rector over who should benefit from donations made at the chapel. In 1466, a papal bull confirmed the chapel's privileges and at the same time, the pope granted an indulgence of forty days to those who visited the chapel on the feast of Saint Thomas, 29 December. As the Reformation in England began, so the fortunes of the chapel waned; there being only one priest and one clerk by 1541, instead of the five priests who had been employed there in the previous century.[5] King Henry VIII was keen to end the veneration of saints, in many cases removing the valuable decoration of shrines for the enrichment of the Treasury. In particular, the king was determined to end the cult of Thomas à Becket, who had upheld the privileges of the church against royal authority. An order was issued in 1538 to change the dedication to Saint Thomas the Apostle and in the following year, a painter from Southwark was employed to cover over images of Becket on the chapel walls. This was not enough to ensure the chapel's survival however.[6]

In 1548, the last chaplain was ordered to deliver the chapel's goods and ornaments to the bridge-master and lock the doors.[5] In the following year, it was ordered that "the chapell upon the same bridge be defaced, and be translated into a dwellyng-house, with as moche spede as they convenyentlye may".[6]

Later use and demolition

A watchman was employed as caretaker until 1553, when the chapel was finally leased to a grocer, the Upper Chapel becoming his house and shop and the Lower Chapel his warehouse.[6] An extra floor was created in the Upper Chapel by inserting stout wooden beams at the level of the top of the columns.[7]

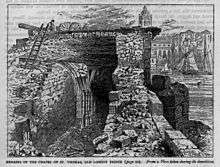

During repairs to the spiral staircase in 1737, an unmarked tomb was discovered and the remains inside were assumed to be those of Peter de Colechurch.[8] A box containing some bones which were said to come from this tomb was preserved in the London Museum, however when the bones were analysed in 1997, only one fragment was human, the others were from a cow and a goose.[9] In 1751, the Chapel House, as it became known, passed into the hands of a firm of stationers, run by partners Thomas Wright and William Gill, who later both became Lord Mayors of London.[10] Due to the congestion of the narrow street and the decrepit condition of the various buildings on the bridge - even newly built houses quickly began to subside - it was decided to clear away all these structures and redevelop the roadway. The London Bridge Act 1756 allowed the City Corporation to buy the leases of all the properties on the bridge,[11] and work on dismantling the houses in the centre section, including the Chapel House, started in February 1757.[12] However, the cellar that had once been the Lower Chapel continued in use as a store for paper and other stationery, being reported in a newspaper in 1798 to be "safe and dry".[10] A new London Bridge was eventually built alongside the old and was opened with great ceremony on 1 August 1831; the demolition of the old bridge commenced straight away. During the first half of 1832, the arches and then the piers were dismantled, exposing the vaults and columns of the Lower Chapel, an event that was recorded by Edward William Cooke in an engraving published in 1833.[13]

References

Bibliography

- Page, William (editor) 1909, A History of the County of London: Volume 1, London Within the Bars, Westminster and Southwark, Victoria County History, London

- Pierce, Patricia (2001), Old London Bridge, Headline Book Publishing, ISBN 9780747234937

- Thomson, Richard (1827), Chronicles of London Bridge, Smith, Elder & Co, London