Charles Starkweather

| Charles Starkweather | |

|---|---|

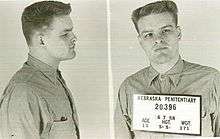

Mug shots of Starkweather | |

| Born |

Charles Raymond Starkweather November 24, 1938 Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died |

June 25, 1959 (aged 20) Lincoln, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Electrocution via electric chair |

| Nationality | American |

| Criminal charge | First degree murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Partner(s) | Caril Ann Fugate |

Time at large | 60 days |

| Killings | |

| Victims |

|

Span of killings | December 1, 1957–January 29, 1958 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | Nebraska, Wyoming |

| Location(s) |

Lincoln and Bennet, Nebraska Douglas, Wyoming |

| Killed | 11 |

| Weapons |

Winchester Model 1906 .410 Stevens Model 59A .38-caliber revolver Knife |

Date apprehended | January 29, 1958 |

| Imprisoned at | Nebraska State Penitentiary |

Charles Raymond "Charlie" Starkweather (November 24, 1938 – June 25, 1959)[1] was an American teenaged spree killer[2] who murdered eleven people in the states of Nebraska and Wyoming in a two-month murder spree between December 1957 and January 1958. All but one of Starkweather's victims were killed between January 21 and January 29, 1958, the date of his arrest. During the murders committed in 1958, Starkweather was accompanied by his 14-year-old girlfriend, Caril Ann Fugate.

Starkweather was executed 17 months after the events, and Fugate served 17 years in prison before her release in 1976.[3] The Starkweather-Fugate spree has inspired several films, including The Sadist (1963), Badlands (1973), Kalifornia (1993), and Natural Born Killers (1994). Starkweather's electrocution in 1959 was the last execution in Nebraska until 1994.

Early life

Starkweather was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, the third of seven children of Guy and Helen Starkweather.[4] The Starkweathers were a poor but respectable family of working-class background. Guy Starkweather was by all accounts a mild-mannered man; he was a carpenter who was often unemployed due to rheumatoid arthritis in his hands. During Guy's periods of unemployment, Helen Starkweather supplemented the family's income as a waitress.

Starkweather attended Saratoga Elementary School, Irving Junior High School, and Lincoln High School. In contrast to his family life, Starkweather remembered nothing positive of his time at school.[5] Starkweather was born with genu varum, a mild birth defect that caused his legs to be misshapen. He also suffered from a speech impediment, which led to constant teasing by classmates.[5]

The only subject which Starkweather excelled at was gym.[4] It was in gym class where he found a physical outlet for his growing rage against those who bullied him. Starkweather used his newfound physicality to begin bullying those who had once bullied him,[6] and soon his rage stretched beyond those who had bullied him to anyone whom he happened to dislike. Starkweather soon went from being considered one of the most well-behaved teenagers in the community to one of the most troubled. His high school friend Bob von Busch would later recall:

| “ | He could be the kindest person you've ever seen. He'd do anything for you if he liked you. He was a hell of a lot of fun to be around, too. Everything was just one big joke to him. But he had this other side. He could be mean as hell, cruel. If he saw some poor guy on the street who was bigger than he was, better looking, or better dressed, he'd try to take the poor bastard down to his size.[7] | ” |

Relationship with Caril Ann Fugate

In 1956, eighteen-year-old Charles Starkweather was introduced to thirteen-year-old Caril Ann Fugate. Starkweather had dropped out of Lincoln High School in his senior year and became employed at a Western Union newspaper warehouse.[4][6] He sought employment there because the warehouse was located near Whittier Junior High School in Lincoln, where Caril was a student. His employment allowed him to visit her every day after school. Starkweather was considered a poor worker and his employer later recalled, "Sometimes you'd have to tell him something two or three times. Of all the employees in the warehouse, he was the dumbest man we had."

Starkweather taught Fugate how to drive, and one day she crashed his 1949 Ford into another car. Starkweather's father paid the damages, as he was the owner of the vehicle. This caused an altercation between Starkweather and his father. Refusing to condone his son's behavior, he banished his son from the family home. Starkweather quit his job at the warehouse and became employed as a garbage collector for minimum wage.[4] Starkweather began progressing towards his nihilistic views on life, believing that his current situation was the final determinant of how he would live the rest of his life. He used the garbage route to begin plotting bank robberies and finally conceived his own personal philosophy by which he lived the remainder of his life: "Dead people are all on the same level".

1957: First murder

Late on November 30, 1957, in Lincoln, Starkweather became angry at service station attendant Robert Colvert for refusing to sell him a stuffed animal on credit. He returned several times during the night to purchase small items, then finally, brandishing a shotgun, forced Colvert to hand over $100, then drove him to a remote area. After Colvert was injured during a struggle over the gun, Starkweather killed him with a shot to the head.[5] Leaving the service station, he immediately confessed to Fugate that he had only robbed Colvert but that someone else had killed him. Fugate later told police that she did not believe Starkweather's story, but pretended to go along out of fear. Starkweather later claimed that after this first murder, he believed he had transcended his former self, reaching a new plane of existence in which he was outside the law and could commit any crime without guilt or fear of repercussion.

1958 murder spree

On January 21, 1958, Starkweather went to Fugate's home.[1] Fugate was not there, and after Fugate's mother and stepfather, Velda and Marion Bartlett, told him to stay away, Starkweather killed them with his shotgun, then killed their two-year-old daughter Betty Jean by strangling and stabbing her.[5] After Fugate arrived, they hid the bodies behind the house. They remained in the house until shortly before the police, alerted by Fugate's suspicious grandmother, arrived on January 27.[5]

Starkweather and Fugate drove to the Bennet, Nebraska, farmhouse of seventy-year-old August Meyer, a family friend. Starkweather killed him with a shotgun blast to the head.[5] He also killed Meyer's dog.[8]

Fleeing the area, Starkweather and Fugate drove their car into mud and abandoned the vehicle. When Robert Jensen and Carol King, two local teenagers, stopped to give them a ride, Starkweather forced them to drive back to an abandoned storm shelter in Bennet, where he shot Jensen in the back of the head. He then attempted to rape King but was unable to. He became angry with her and shot her to death. Starkweather later admitted shooting Jensen, but claimed that Fugate shot King. The two fled Bennet in Jensen's car.

Starkweather and Fugate drove to a wealthy section of Lincoln, Nebraska where they entered the home of industrialist C. Lauer Ward and his wife Clara.[5] Both Clara and maid Lillian Fencl were fatally stabbed, and Starkweather snapped the neck of the family dog. Starkweather later admitted throwing a knife at Clara; however, he accused Fugate of inflicting the multiple stab wounds that were found on her body. When Lauer Ward returned home that evening, Starkweather shot and killed him. Starkweather and Fugate filled Ward's black 1956 Packard with stolen jewelry from the house and fled Nebraska.

The murders of the Wards and Fencl caused an uproar within Lancaster County,[5] with all law enforcement agencies in the region thrown into a house-by-house search for the killers. Governor Victor E. Anderson contacted the Nebraska National Guard, and the Lincoln chief of police called for a block-by-block search of the city. Several sightings of Starkweather and Fugate were reported, with charges of incompetence against the Lincoln Police Department for their inability to capture the two.

Needing a new car because of the high profile of Ward's Packard, they found traveling salesman Merle Collison sleeping in his Buick along the highway outside Douglas, Wyoming. After they woke Collison, they shot him. Starkweather later accused Fugate of performing a coup-de-grace after his shotgun jammed. Starkweather claimed Fugate was the "most trigger happy person" he had ever met. The salesman's car had a push-pedal emergency brake, which was something new to Starkweather. While attempting to drive away, the car stalled. He tried to restart the engine and a passing motorist stopped to help. Starkweather threatened him with the rifle, and an altercation ensued. At that moment, a deputy sheriff arrived on the scene. Fugate ran to him, yelling something to the effect of: "It's Starkweather! He's going to kill me!" Starkweather tried to evade the police, exceeding speeds of 100 miles per hour (160 km/h). A bullet shattered the windshield and flying glass cut Starkweather deep enough to cause bleeding. He then stopped and surrendered. Converse County Sheriff Earl Heflin said, "He thought he was bleeding to death. That's why he stopped. That's the kind of yellow son of a bitch he is."[9]

Trial and execution

Starkweather chose to be extradited to Nebraska and he and Fugate arrived there in late January 1958. He believed that either state would have executed him. He was not aware that the Governor of Wyoming at the time was an opponent of the death penalty.[10] Starkweather first claimed Fugate was captured by him and had nothing to do with the murders; however, he changed his story several times, finally testifying at Fugate's trial that she was a willing participant. Fugate has always maintained that Starkweather was holding her hostage by threatening to kill her family, claiming she was unaware they were already dead. Judge Harry A. Spencer did not believe Fugate was held hostage by Starkweather, as she had had numerous opportunities to escape. When Starkweather was first brought in to the Nebraska penitentiary he stated that he believed that he was supposed to die and that if he was executed, then Fugate should be too.

Starkweather was found guilty and received the death penalty for the murder of Robert Jensen, the only murder for which he was tried. He was executed by electric chair at the Nebraska State Penitentiary in Lincoln, Nebraska, at 12:04 a.m. on June 25, 1959.[11] He is buried in Wyuka Cemetery in Lincoln along with five of his victims, including Mr. and Mrs. Ward.[12][13]

Fugate received a life sentence on November 21, 1958. She was paroled in June 1976 after serving 17 1/2 years at the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women in York, Nebraska. She settled in Lansing, Michigan, where she changed her name and worked as a janitor at a Lansing hospital. Fugate married in 2007 and, apart from a radio interview in 1996, has refused to speak of the murder spree.[14]

Upon marrying Frederick Clair, she changed her name to Caril Ann Clair and was living in Stryker, Ohio when she was seriously injured and her husband killed in a car crash on August 5, 2013.[15]

Victims

- Robert Colvert (21), gas station attendant

- Marion Bartlett (58), Fugate's stepfather

- Velda Bartlett (36), Fugate's mother

- Betty Jean Bartlett (2), Velda and Marion Bartlett's daughter; Fugate's half sister

- August Meyer (70), Starkweather's friend

- Robert Jensen (17), boyfriend to Carol King

- Carol King (16), girlfriend to Robert Jensen

- C. Lauer Ward (47), wealthy industrialist

- Clara Ward (46), C. Lauer Ward's wife

- Lillian Fencl (51), Clara Ward's maid

- Merle Collison (34), traveling salesman

Depictions in media

Film and television

The Starkweather–Fugate case inspired the films The Sadist (1963), Badlands (1973), Kalifornia (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994) and Starkweather (2004). "A Case Study of Two Savages," a 1962 episode of the TV series Naked City was also inspired by the Starkweather killings. The made-for-TV movie Murder in the Heartland (1993) is a biographical depiction of Starkweather with Tim Roth in the starring role, while Stark Raving Mad (1983), a film starring Russell Fast and Marcie Severson, provides a fictionalized account of the Starkweather–Fugate murder spree.

The 1996 Peter Jackson film The Frighteners features a central plot elements with a Starkweather-inspired killer who goes on a similar murder spree complete with a kidnapped female accomplice. The fourth episode, "Dangerous Liaisons," of season three from the ID series, Deadly Women (aired September 2, 2010) covers the Starkweather–Fugate murders.

"The Thirteenth Step", the January 11, 2011 episode of Criminal Minds, depicts newlyweds on a North Dakota/Montana killing spree similar to the Starkweather–Fugate case.[16] On the Fox Files episode "Mass Murder on the Great Plains" (aired August 26, 2013), Claudia Cowan interviews Del Harding, who covered the story for the Lincoln Star.

Literature

The 1974 book Caril is an unauthorized biography of Caril Ann Fugate written by Ninette Beaver. Liza Ward, the granddaughter of victims C. Lauer and Clara Ward, wrote the 2004 novel Outside Valentine, based on the events of the Starkweather–Fugate murders.

The 1997 novel Not Comin' Home to You by Lawrence Block fictionally parallels the Starkweather and Fugate spree. Horror author Stephen King was strongly influenced by reading about the Starkweather murders when he was a youth, keeping a scrapbook about them[17] and later creating many variations on Starkweather in his work.

Visual arts

In 2011, art photographer Christian Patterson released Redheaded Peckerwood,[18] a collection of photos made each January from 2005 to 2010 along the 500-mile route traversed by Starkweather and Fugate. The book includes reproductions of documents and photographs of objects that belonged to Starkweather, Fugate, and their victims, several of which Patterson discovered while making his photographs and had never been seen publicly before.[19] Comic book series Northlanders referenced the story in its 2010 story arc Metal.[20]

Music

The Philadelphia band Starkweather, formed in 1989, is named for Charles Starkweather.

Bruce Springsteen's 1982 song "Nebraska" is a first-person narrative based on the Starkweather events; likewise "Badlands" is full of themes regarding alienation and resentment by the protagonist. The song "Badlands" by Church of Misery on their album Houses of the Unholy centers on the murders and is told from a first-person perspective.

The Del Shannon song "Keep Searchin' (We'll Follow The Sun)" was a fictional love-letter written from Charles Starkweather and is based on testimony from his trial.

Starkweather was also featured in Billy Joel's "We Didn't Start the Fire", referenced in the first part of the line "Starkweather homicide, children of Thalidomide."

The San Francisco pop-punk Band J Church's 1994 song "Hate So Real" is a first-person tale of the murders, including the names of several of the victims and the line "Now Caril can't deny me/ and to this day I swear/ she should be sittin' on my lap when I go to the chair." Also, their song "In Vain" from their 1993 release Yellow, Blue and Green features themes from the Starkweather/Fugate saga and pictures of the two featured in the artwork.

A photo of Starkweather is used as the cover of hardcore punk band Blood for Blood's 1997 7" record Enemy.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 Wishart, David J. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. U of Nebraska Press. p. 462. ISBN 978-0-8032-4787-1. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ↑ Rule, Ann (2004). Kiss Me, Kill Me: Ann Rule's Crime Files. Simon and Schuster. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-671-69139-4. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ↑ Flowers, R. Barri; H. Loraine Flowers (April 2005). Murders In The United States: Crimes, Killers And Victims Of The Twentieth Century. McFarland. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7864-2075-9. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Charles Starkweather Archived November 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., biography.com; accessed June 21, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, retrieved (December 9, 2009)

- 1 2 World of Criminal Justice on Charles Starkweather, BookRags.com; accessed June 21, 2015.

- ↑ Allen, William. Starkweather: The Story of a Mass Murderer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976. Print.

- ↑ Leyton, Elliot. Hunting Humans (p. 205); Pocket Books (1988); ISBN 9780671659615

- ↑ Joe McGowan, "Youth Who Slew Ten Captured in Wyoming", Associated Press report in Alton (IL) Evening Telegraph, January 30, 1958, p. 1.

- ↑ Profile, trutv.com; accessed June 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Starkweather Executed: Calm To The End, No Final Words". The Miami News. June 25, 1959. p. 1-A. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ↑ Zimmer, Ed. "Wyuka Cemetery: A Driving & Walking Tour", nebraskahistory.org; accessed June 21, 2015.

- ↑ Nebraska State Historical Society website, nebraskahistory.org; retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ Lee, Melissa (April 1, 2009). "Starkweather's family still lives with legacy". Lincoln Journal-Star. Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Starkweather's girlfriend in critical condition". Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Criminal Minds Recap: The Thirteenth Step". CBS.com. October 14, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ↑ Stephen King interview, uncut and unpublished. guardian.co.uk; accessed June 21, 2015.

- ↑ Sante, Luc (September 8, 2012). "Violence, Dissected". The New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ Mack Publishing

- ↑ "Brian Wood On Northlanders: Metal". Warren Ellis. June 10, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

References

- Allen, William. Starkweather: Inside the Mind of a Teenage Killer. 2004, Emmis Books, 240 pages. ISBN 978-1-57860-151-6

- Del Harding, reporter for the Lincoln, Nebr., Star, who covered the murders, the Starkweather and Fugate trials, and Starkweather's execution.

- Newton, Michael (February 1998). Waste Land: The Savage Odyssey of Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-00198-8. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- O'Donnell, Jeff (1993). Starkweather: A Story Of Mass Murder On The Great Plains. J & L Lee Publishers. ISBN 978-0-934904-31-5. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

External links

- Bardsley, Marilyn. Charles Starkweather & Caril Fugate. Crime Library. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- Charles Starkweather at Find a Grave

- Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate Trials: 1958 at law.jrank.com

- "Redheaded Peckerwood" on Christian Patterson web site.

- Nebraska State Historical Society