Chicago Portage

| Chicago Portage | |

|---|---|

|

Maps of the Chicago Portage, on a sign at Chicago Portage National Historic Site | |

| Elevation | 589 ft (180 m)[1] |

| Traversed by |

Mud Lake (historic), Illinois and Michigan Canal (historic), Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, several railroads, numerous roads including |

| Location | (historic) 3100 West 31st Street, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, US |

| Range | Valparaiso Moraine |

| Coordinates | 41°50′14″N 87°42′8″W / 41.83722°N 87.70222°W |

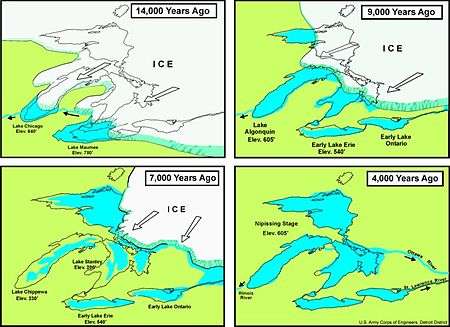

The Chicago Portage is a water gap connecting the watersheds (BrE: drainage basins) and the navigable waterways of the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes. It cuts through the Valparaiso Moraine, crossing the Saint Lawrence River Divide that separates the Great Lakes and Gulf of St. Lawrence watersheds from the Gulf of Mexico watershed, making it one of the most strategic points in the interior of the North American continent. The saddle point of the gap is within the City of Chicago, and the Chicago Portage is a reason Chicago exists and has developed to become the immensely important city that it is,[2] ranking 7th in the world in the 2014 Global Cities Index. The official flag of the City of Chicago is a stylized map of the Chicago Portage, with four red stars symbolizing city history, separating two blue stripes symbolizing the two great waters that meet at the city.[3]

Flow direction

A principal feature of the Chicago Portage water gap is that water can flow through it in either direction across the continental divide. It has flowed from east to west, west to east, or not at all. There have been two long-term reversals, and short-term reversals still happen today. Initially, water flowed from east to west starting about 10,000 years ago. About 3,000 years ago, this flow mostly stopped, and the Chicago Portage became a wind gap, except during floods when it flowed from west to east. In the year 1900, it was reversed to again flow continuously from east to west, except during floods when it can be reversed to flow from west to east.[4]

History

The Chicago Portage was formed as the Wisconsin glaciation retreated northward about 10,000 years ago, leaving behind Lake Chicago consisting of its meltwater. Lake Chicago found its only outlet at its southwestern edge, where it overflowed the Valparaiso Moraine which encircles the southern half of the Lake Chicago/Lake Michigan basin, creating the Chicago Outlet River. This was a substantial river, carving the channel later used by the main and south branches of the Chicago River, and the Des Plaines River.[5] Eventually the glaciers melted far enough northward that Lake Chicago was connected to Lake Huron, a combination sometimes called Lake Michigan-Huron, resulting in a significant drop in the water level. Until perhaps 3,000 years ago, the combined lakes had two outlets, one at Chicago, and the other via the St. Clair River at Port Huron, Michigan. Eventually the St. Clair River outlet eroded slightly more quickly, resulting in stream capture of the Chicago Outlet River as the water level of Lake Michigan-Huron gradually declined. However, until man-made canals and levees were built within the past 170 years, during periods of heavy rain or downstream ice dams, the Des Plaines River could still flood eastward through a marshy area of the bed of the former Chicago Outlet River known as Mud Lake, across the continental divide into the Chicago River and then into Lake Michigan.

The saddle point of the gap, where the continental divide crossed the water course, was historically at the eastern end of Mud Lake, where Native Americans portaging their canoes across the low point of the divide carved a slight gouge. This location is now 3100 West 31st Street in Chicago.[1] However, the alterations reversing the flow of the Chicago River in 1900 moved the continental divide to pass through the heart of Downtown Chicago, and moved the saddle point to the Chicago Locks at the mouth of the Chicago River on the Lake Michigan shore. When heavy rain causes the Chicago River to flood, the Chicago Locks can still be opened to release floodwater across the continental divide into Lake Michigan, similar to the historic Des Plaines River floods through Mud Lake across the divide.[4]

As the first Americans extended their settlement northward following the retreating glaciers, they found the Chicago Portage to be a convenient transportation route between the shores of Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River in the interior. The portage was revealed to Europeans in 1673 when the French explorers, Louis Joliet (Jolliet) and Father Jacques Marquette, were canoeing upstream on the Mississippi River. They were guided to the portage by local Native Americans and continued along the Illinois and Des Plaines Rivers. Near where the Des Plaines was separated from the Chicago River they encountered a swampy area known as Mud Lake. Seasonally, this was a shallow waterway or a muddy slough of 8 miles (13 km). This connected the Des Plaines to the Chicago River, which then flowed into Lake Michigan. When French explorer Robert de La Salle surveyed the strategic importance of this connection, he is said to have stood at that point on the shore of Lake Michigan and stated, "This will be the gate of empire, this the seat of commerce."[6]

At the time, the Chicago Portage was the most strategic location in the interior of the North American continent and in particular between the French cities of Montreal and New Orleans. Control of the Portage was critical if the French were to contain English expansion in the New World. According to Joliet, a canal of "half a league'' (about 2 miles (3.2 km)) across the Chicago Portage would allow easy navigation from Lake Erie to the Gulf of Mexico.[7]

In 1848, the Illinois and Michigan Canal was opened, breaching the water divide and enabling navigation between the two waterways. In 1900 it was replaced by the larger Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal. After the Chicago River was reversed and diverted to the new canal, the Mississippi watershed is now separated from the Great Lakes by only the Chicago Locks. The quantity of water allowed to pass (and thus diverted from the St. Lawrence River) is regulated by the U.S. and Canadian International Joint Commission.

Mud Lake

From about 3,000 years ago until the year 1900, the Des Plaines River and the Chicago River were connected in the ancient stream bed of the Chicago Outlet River by a slough or swampy area known as Mud Lake. This remnant was left behind when the water level of Lake Michigan-Huron dropped as the St. Clair River captured the flow of the Chicago Outlet River. Mud Lake could be wet, dry, marshy, or frozen, depending on the season and the weather, making it a difficult, albeit very valuable, transportation route. It was drained in several stages, starting with the construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1848, which bisected it. Several other attempts were made to drain Mud Lake, with the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal finally accomplishing this in 1900.

A small remnant of Mud Lake still exists as a wetland area in Forest View, between the Stevenson Expressway, railroad tracks, and West 51st Street, near the Forest View water tower.[1] This isolated remnant of Mud Lake has been prevented from draining into the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal by the levees of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, the railroad lines, and later the Stevenson Expressway which was built on top of the old I&M Canal in 1964. The rest of Mud Lake is today covered by industrial areas of the City of Chicago.

Chicago Portage National Historic Site

The Chicago Portage National Historic Site is a National Historic Site [8] in Lyons, Cook County, Illinois, United States. Preserved within the park is the western end of the historic portage linking the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River, thereby linking the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. The wild onion that gave Chicago its name thrives here. The site is the only part of the historic Chicago Portage that remains in a natural and protected state more or less as it existed when revealed to French explorers Louis Joliet (Jolliet) and Father Jacques Marquette by Native Americans.[9]

Gallery

|

See also

- Chicago River

- Geography of Chicago

- Valparaiso Moraine

- Lake Chicago

- Saint Lawrence River Divide

- Laurentian Divide

- Eastern Continental Divide

- Stevenson Expressway

- Illinois and Michigan Canal

- Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal

References

- 1 2 3 Vierling, Phillip E. "Mud Lake - I, Chicago Portage Ledger, Vol II No. 1, January/April 2001.". Carnegie Mellon University Libraries. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- ↑ "The Chicago Portage National Historic Site". Friends of the Chicago Portage. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "Chicago Facts: Municipal Flag". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- 1 2 Gallardo, Michelle. "2 locks opened during record rainfall, July 25, 2011". WLS-TV. Retrieved 2012-07-30.

- ↑ Alden, William C. (1902). "Epoch of Glacial Retreat: Lake Chicago, Geologic Atlas of the United States, Number 81". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ Chicago Today and Tomorrow, by William Joseph Showalter, Nationional Gerographic Magazine, January 1, 1919

- ↑ Solzman, David M. "Encyclopedia of Chicago: Portage". Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

- ↑ "CHICAGO PORTAGE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE". Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

- ↑ "The Future of The Past". Friends of the Chicago Portage. Retrieved 2012-08-23.

External links

- Friends of the Chicago Portage official site

- National Park Service

- Stateparks.com

- Carnegie Mellon University Libraries: Chicago Portage Ledger

- 3-D Photosynth of the Sculpture

- Jolliet and La Salle's Canal Plans at Encyclopedia of Chicago

- The Continental Divide in Oak Park

- Chicago Portage History