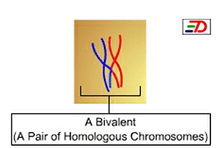

Bivalent (genetics)

A bivalent, sometimes referred to as a tetrad, is the association of a pair of homologous chromosomes physically held together by at least one DNA crossover. This physical attachment allows for alignment and segregation of the homologous chromosomes in the first meiotic division.

Formation

The formation of a bivalent occurs during the first division of meiosis (in the pachynema stage of Meiotic prophase 1). In most organisms, each replicated chromosome (composed of two identical sister chromatids[1][2]) elicits formation of DNA double-strand breaks during the leptotene phase.[3] These breaks are repaired by homologous recombination, that uses the homologous chromosome as a template for repair. The search for the homologous target, helped by numerous proteins collectively referred as the synaptonemal complex, cause the two homologs to pair, between the leptotene and the pachytene phases of Meiosis I.[4] Resolution of the DNA recombination intermediate into a crossover exchanges DNA segments between the two homologous chromosomes at a site called chiasma (or chiasmata). This physical strand exchange and the cohesion between the sister chromatids along each chromosome ensure robust pairing of the homologs in Diplotene phase. The structure, visible by microscopy, is called a bivalent.[5]

Structure

A bivalent is the association of two replicated homologous chromosomes having exchanged DNA strand in at least one site called chiasmata. Each bivalent contains a minimum of one chiasmata and rarely more than three. This limited number (much lower than the number of initiated DNA breaks) is due to crossover interference, a poorly understood phenomenon that limits the number of resolution of repair events into crossover in the vicinity of another pre-existing crossover outcome, thereby limiting the total number of crossovers per homologs pair.[4]

Function

At the meiotic metaphase I, the cytoskeleton put the bivalents under tension by pulling each homolog in opposite direction (contrary to mitotic division where the forces are exerted on each chromatid). The anchorage of the cytoskeleton to the chromosomes takes place at the centromere thanks to a protein complex called kinetochore. This tension results in the alignment of the bivalent at the center of the cell, the chiasmata and the distal cohesion of the sister chromatids being the anchor point sustaining the force exerted on the whole structure. Impressively, human female primary oocytes remains in this tension state for decades (from the establishment of the oocyte in metaphase I during embryonic development, to the ovulation event in adulthood that resume the meiotic division), highlighting the robustness of the chiasma and the cohesion that hold the bivalents together.[6]

References

- ↑ Lefers, Mark. "Northwestern University Department of Molecular Biosciences". Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ "University of Arizona Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics". The Biology Project. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- ↑ Padmore, R.; Cao, L.; Kleckner, N. (1991-09-20). "Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae". Cell. 66 (6): 1239–1256. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90046-2. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 1913808.

- 1 2 Zickler, Denise; Kleckner, Nancy (2015-06-01). "Recombination, Pairing, and Synapsis of Homologs during Meiosis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (6). doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016626. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 4448610

. PMID 25986558.

. PMID 25986558. - ↑ Jones, Gareth H.; Franklin, F. Chris H. (2006-07-28). "Meiotic crossing-over: obligation and interference". Cell. 126 (2): 246–248. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.010. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 16873056.

- ↑ Herbert, Mary; Kalleas, Dimitrios; Cooney, Daniel; Lamb, Mahdi; Lister, Lisa (2015-04-01). "Meiosis and maternal aging: insights from aneuploid oocytes and trisomy births". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 7 (4): a017970. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a017970. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 4382745

. PMID 25833844.

. PMID 25833844.