Classe, ancient port of Ravenna

Classe was a military port located 4 km (2.5 mi) east south east from Ravenna, Italy.[1] It was near the head of the Adriatic coast.[2] For almost five hundred years it was an important strategic military port. When it was not being used as a military port, it was an important commercial port for the imperial capital of Ravenna in the Roman Empire.[3] Classe comes from the Latin word classis, meaning fleet.

Republican Period

There was a small port and harbor for commercial trade.[4] The city of Ravenna, north of the harbor, was founded in the late 3rd or early 2nd century BC.

Early Roman Imperial Period

Origins of Classe

Sometime between 35 and 12 BCE,[5] Octavian (later known as Augustus) established Ravenna's harbor as one of the home ports for his new Roman navy. South of the harbor, the area was occupied mainly by cemeteries, but by the 2nd century AD a town, later known as Classe, had grown up.

Augustus may have chosen this site because of its strategic position. The area in which Augustus wanted to construct Classe was in a lagoon.[6] It was impregnable from land and surrounded by marshes. The base was artificially constructed in this lagoon.[7] Unlike the ports of Portus or Ostia, Classe did not feature a hexagonal basin. Instead the base installations were built on stilts.[8] Once those were in place the port was made of large oak beams. By the 1st century CE the builders had incorporated ceramic fragments. By the 2nd century, it was redone with bricks.[9] Augustus designed the port for military purposes only.[10] The town had only one weakness, access to fresh water. This obstacle was overcome by the Emperor Trajan who built a 35 km (22 mi) long aqueduct to Ravenna, that might also have supplied Classe.[11] After the fleet was built, the population of the soldiers and their families living there grew slowly but steadily.[12] For the next three hundred years, Classe would be one of Rome’s most important naval bases, the home of the eastern Mediterranean fleet[13] The 3rd-century historian Cassius Dio states that the fleet had two hundred and fifty ships. This is the only account that survived to this day and it is only because it was quoted by Jordanes, a 6th-century historian.[9]

Society

Before Augustus' establishment of the fleet, there is no evidence of any habitation in the area that became Classe. As of today, archeologists have only found remains of cemeteries from this time period. It is unknown if these cemeteries were pagan or Christian. However, they were most likely pagan because archeologists do not find evidence of a population returning until the 2nd century. This coincides with the rise of Christianity in Classe.[14]

Later Roman Imperial Period

Due to the crisis of the third century, Ravenna and the port began to decline.[15] The city of Ravenna was sacked at least twice in the 250s and 260s, and the harbor was no longer maintained; it started drying out and began filling with silt.[16] Despite this, as early as 306, Roman emperors started staying at Ravenna in order to watch the harbor to see if any enemies were close.[17] When Ravenna was chosen as an official western imperial capital in 402, Classe became more prosperous than ever, and the residential area to the south of the harbor was surrounded by a wall in the late 4th century[18] A vital part of the royal administration was its grain warehouse and distribution.[19] Even after 476, when Ravenna was no longer a Roman imperial capital, it and its port survived, and the town of Classe was restored under the Ostrogothic king Theodoric.

Society

While Ravenna was an imperial capital some sailors and their families lived there. However, the majority of the sailors and their families lived in the vast barracks of the imperial fleet.[20] Because there were no other large cities in the area, families stayed, putting down roots in Ravenna and Classe.[21] (note that sailors were not legally allowed to be married while enlisted in the fleet).[12] As for the government of Classe, it was overruled by the imperial prefect of the imperial fleet.[22] However, once Ravenna became the imperial capital in 402, it appears Classe fell under its jurisdiction.

Christian presence

Archeological remains show Christianity was an important part of life in Classe. “It became a focus of the earliest Christian community.”[16] Cemeteries from the late 2nd century show the beginning of Christianity in Classe. Starting in the 4th century, Classe acquired several magnificent churches, as well as its own baptistery. “The centerpiece of Christian worship in the Classe region both geographically and symbolically, was the church dedicated to the first bishop of Ravenna, Saint Apollinare”, which was built in the 540s[23] Sant'Apollinare in Classe is the only church from Classe still standing today. Other churches near Sant'Apollinare were dedicated to other early bishops who had been buried there, as this was the region in which cemeteries were located in the Roman period.[24] There is no evidence of Classe ever having its own bishop. This was probably because Classe was so much smaller than Ravenna, there was no need for Classe to have its own bishop.[25]

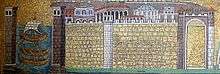

Finally, the church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in the city of Ravenna features a mosaics depicting the harbor of Classe in the 520s. The city of Classe is walled with an amphitheatre, basilica and the entrance of the harbor is flanked by two lighthouses.[10] The remains of the lighthouses have never been found.

Classe Fleet

Western

Classe could hold a fleet of two hundred and fifty ships and could accommodate arsenals, magazines and barracks.[26] The fleet consisted of triremes, quadriremes and liburnians (light vessels). These ships were named after gods, goddesses and rivers. The fleet employed ax makers, carpenters, doctors, flag bearers, horn players, officers, oarsmen, pilots, repair personnel, rhythm keepers for oarsmen, scribes, sailors, and weapons masters. There were as many as ten thousand men connected to the fleet in some way.[12] The fleet was used primarily to keep the peace in the Mediterranean. The fleet's main focuses were the Adriatic Sea and Aegean Sea, though it patrolled the waters of the Mediterranean as far away as Spain.[27] In 24 the fleet was used to put down a slave revolt in Brundisium. When the fleet was not being used for military purposes, it was used to protect merchant ships from pirates.[28] Although little evidence exists, recent scholarly consensus rejects the assumption that there were no pirates in the Mediterranean during the early Empire, preferring to credit the fleet at Classe with their suppression. Tombstones from sailors of the fleet have been unearthed there.[29] By 69 the Classe fleet had five thousand ships.[30] By 324 the western “Augustan navy” was gone. This was most likely because the western half of the empire was preoccupied with civil war. Emperor Constantine was engaged in fighting civil wars with his fellow tetrarch emperors Maxentius and Licinius for sole control of the empire. The empire did not have the means or resources to have a navy at Classe. For further information, there is a detailed article on the Roman navy.

Eastern

The eastern part of the Roman Empire understood how important Classe was as a military port. Scholars are unclear as to when the transition between the western focused navy and the eastern focused navy took place; estimates are between 324 and 383. This new eastern navy was a permanent fleet in Classe. The fleet was used to control the Aegean Sea and the eastern part of the Mediterranean. Later it was used to help reclaim the lost Roman territory in the west, such as Italy.[31] However, between 383 and 450 the standing fleet disappeared.[32]

Ostrogothic Period

Roman imperial rule came to an end when in 476, Odoacer, a Germanic magister militum, deposed the Western emperor Romulus Augustulus and declared himself king of Italy. By the 480s, the emperor in the east, Zeno, was determined to put an end to Odoacer and his kingdom. Zeno encouraged Theodoric to invade Italy and rule it as a viceroy. Theodoric was successful in destroying Odoacer’s kingdom, but he subsequently declared himself king of Italy, and established his capital at Ravenna. The Ostrogothic Kingdom of Theodoric the Great lasted between 490 and 540.[33] The Classe that Theodoric inherited was no longer a first class military port. Part of the harbor was completely dried up; however, Theodoric worked to repair the harbor and port.[34] Despite this renovation, the port was no longer an important military naval outpost. In fact Classe was taken off of the formal army register.[31] Instead, the port became an important commercial port for all of northern Italy.[34]

Exarchate of Ravenna

The eastern half of the empire had been connected to Classe since 324 through the navy. By the first half of the 6th century, the empire had its sights on claiming the port city for its own. Emperor Justinian I opposed the Ostrogothic rule of Italy on the grounds that the Arian sect constituted a heresy. He sent his general Belisarius to recapture Italy, including Ravenna and Classe, for the eastern half of the empire. In 540 Classe was reconquered by Belisarius in the Gothic Wars (535-554). It stayed under eastern control until 751. This time is known as the Exarchate of Ravenna. Justinian, understanding the strategic importance of Classe, once again refurbished the harbor. Classe became the second most important port after Constantinople.[35] Classe in the early 6th century became a prosperous cosmopolitan naval and trading center.[36] Because of this, there was an increase in population. New churches and basilicas were built for the new population, including Sant'Apollinare in Classe, mentioned above.[37] Another major church of this time was the San Severo. Construction on it began in 570 by Archbishop Peter III and was completed Archbishop John II in 582. Upon completion it was dedicated to Ravenna’s 4th-century bishop, Saint Severus.[38]

Lombard War

During the late 6th century, the barbarian group known as the Lombards invaded Ravenna and plundered Classe in 579. The raid was led by Faroald, the Duke of Spoleto, who controlled the cities for a short time. However, Drocdulf, a Sueve who fought for the eastern Empire regained Classe and forced the Lombards to give the cities back to the Eastern Empire.[39] In 717-8 the Lombard duke Faroald captured Classe, but was ordered to withdraw by King Liutprand, who himself captured Classe a few years later and again returned it to the Byzantines. In 751, another king, Aistulf, succeeded in conquering Ravenna. This ended the Exarchate of Ravenna. During the Lombard Wars, while Ravenna was spared for the most part, Classe seems to have been completely destroyed. By this time the harbor had completely dried up. Because of the Lombard Wars and the decay of the harbor, the city of Classe dramatically shrank.[40] After this event, Classe was never again an important port militarily or commercially.

Middle Ages

The Frankish king Pepin the Short drove the Lombards out of Ravenna and Classe in 756; following this, the territory was briefly ruled by the archbishops of Ravenna. Pepin's son Charlemagne's conquest of the Lombard kingdom in 774 saw the two cities turned over to the Pope and they became part of the newly formed Papal States. In the mid-9th century, Classe was raided and sacked by Muslims.[41] Also, sometime in the Middle Ages, the Po River completely destroyed the port. Because of this, archeologists are forced to use other evidence to reconstruct how the port may have looked.[42]

Modern Era

Today Classe is an archaeological site. The main excavation sites are: Podere Chiavichetta, San Severo, Podere Marabina and Saint Probus.[43] The ground under Ravenna and Classe has been sinking for centuries. In fact, it sinks about 16–23 cm (6–9 in) every century. This makes excavating extremely difficult. When archeologists dig they find artifacts at various levels. From 3–6 m (10–20 ft) below the surface there is material dating from Imperial rule; from 2–4 m (6 ft 7 in–13 ft 1 in), material from the Ostrogothic Kingdom; and from 4–8 m (13–26 ft), material from the Republic. Due to the accumulation of silt, the coastline has moved 9 km (5.6 mi) to the east.[44] If visiting Classe, one has to climb to the top of the last watch tower to see the ocean.[45] On 16 July 2015 the archeological site became a museum which is open for visitors.[46]

Main Sites

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe

San Severo

See also

References

Ancient sources

Because of the tumultuous times, few firsthand accounts survive to this day. There are two main sources: Appian, the historian who in 39 BCE stated that: Augustus ordered new buildings at Classe. There is also Cassius Dio who is referenced by Jordanes. This means that archeologists are forced to rely on epigraphic evidence such as wall carvings, mosaics and tombstones when trying to reconstruct what life was like in Classe.

Modern sources

Finding scholarly information on Classe in English is extremely challenging. The most comprehensive book is Ravenna in Late Antiquity by Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis. In it, she discusses the various stages of the port and also gives the most up to date archeological information as of January 2010. Another book in English is Edward Hutton’s The Story of Ravenna, published in 1926. Most of the latest information on Ravenna and Classe can be found in Italian academic journals.

Bibliography

- Appian, Book II of Civil Wars. 2.41

- Bowerstock, G.W., Brown, Peter and Grabored, Olge. "Ravenna" In Late Antiquity: a Guide to the Postclassical World. Cambridge, MA: The Belknop Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Cassius Dio. See Jordanes.

- Charles, Michael. "Transporting the Troops in Late Antiquity: Naves Onerariae, Claudian

and the Gildonic War" In The Classical Journal Volume 100, Number 3 (February/March, 2005) Pages 275-299, published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South.

- Christie, Neil. The City Walls of Ravenna: The Defence of a Capital, A.D. 402-750. In Ravenna e l’Italia fra Goti e Longobardi XXXVI Corso di Cultura sull’Arte Ravennate e Bizantina:(Ravenna), 1989, pp. 113–138.

- Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, January 2010.

- Hassall, Mark. " The Army" in The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 11 The High Emprire A.D. 70 - 192 2nd edition, edited by Alan K. Bowman, Edward Champlin and Andrew Lintott, 9. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Hownblower, Simmon and Spawforth, Antony, eds. "Ravenna" In The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 3rd. edition. New York,NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Hutton, Edward. The Story of Ravenna. Great Britain: J.M. Dent and Sons Limited, 1926.

- Jordanes. 29.151 of Getica. Translated by Charles C. Mierow.

- Kazhdan, Alexander P. and Talbot, Alice-Mary eds. "Ravenna" In The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. 3. New York,NY: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Keppie, Lawrence. "The Army and the Navy: The Navy." In The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 10 The Augustan Empire 43 B.C. - A.D. 69. 2nd edition, edited by Alan K. Bowman, Edward Champlin and Andrew Lintott, 11. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Lewis, Archibald R and Timothy J. Runyan. European Naval and Maritime History 300-1500. Indiana University Press, 1985.

- Pitassi, Michael. The Navies of Rome. United Kingdom: The Boydell Press Woodbridge, March 19, 2009.

- Starr, Chester G. The Influence of Sea Power on Ancient History. New York,NY: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Starr, Chester G. The Roman Imperial Navy 31 B.C. - A.D. 324. Great Britain: Lowe and Brydone Limited 1941.

Citations

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 26.

- ↑ Keppie, The Army and the Navy, 383.; Hornblower, Ravenna, 1294.

- ↑ Bowerstock, Ravenna, 662.

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 27, 30; Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 26.

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 26; Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 229.

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 26; Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 27

- ↑ Starr, Influence of Sea Power, 68

- ↑ Pitassi, Navies of Rome, 206

- 1 2 Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 28

- 1 2 Starr, Roman Imperial Navy, 21

- ↑ Deliyannis,Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 34; in fact, the path of the aqueduct is uncertain, since it brought water from south of the harbor all the way to Ravenna.

- 1 2 3 Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 30

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 26

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity,30, 38

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 36

- 1 2 Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 37

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 30, 34

- ↑ Christie, City Walls of Ravenna, 114; Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 37

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 118

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 229; but there is no evidence at all for this

- ↑ Starr, Royal Imperial Navy, 23

- ↑ Starr, Roman Imperial Navy, 22

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 259

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 38

- ↑ All information on Classe's lack of bishop is in Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 197

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 28-29;Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 28; Charles, Transporting the Troops, 279.

- ↑ Keppie, The Army and the Navy, 383.

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 27

- ↑ Starr, Roman Imperial Navy, 189

- ↑ Pitassi, Navies of Rome, 222

- 1 2 Starr, Roman Imperial Navy, 198

- ↑ Charles, Transporting the Troops, 276

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 137

- 1 2 Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 117

- ↑ Lewis, European Naval, 22

- ↑ Kazhdan, Ravenna, 1773.

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 196, 257

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 274

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 206

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 289

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 260

- ↑ Starr, Roman Imperial Navy, 21 ?? the Po River was nowhere near Classe

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 12

- ↑ Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity, 13

- ↑ Hutton, Story of Ravenna, 230

- ↑

External links

- Appian on Octavian. See section 32

- Jordanes quoting Cassius Dio in Getica. See chapter 29.151

- Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

- Andrea Augenti's official site (Italian)

- Book Augenti contributed to

- 44°23′43.44″N 12°13′8.94″E / 44.3954000°N 12.2191500°E