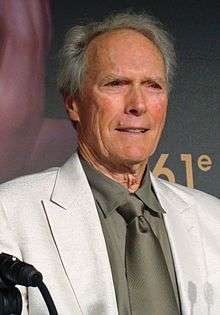

Clint Eastwood in the 1990s

a series on Clint Eastwood |

|---|

Clint Eastwood rose to prominence again in the early 1990s, starting with the film White Hunter Black Heart, an adaptation of Peter Viertel's roman à clef about John Huston and the making of the classic film The African Queen. The film was shot on location in Zimbabwe in the summer of 1989,[1] with some interiors shot in and around Pinewood Studios in England. The small steamboat used in the whitewater scene is the same boat Humphrey Bogart's character captained in The African Queen. The film was closely based on the book, but the ending was changed to the killing of an elephant, in spite of Huston's assertion in his memoir An Open Book (1980) that he had never killed an elephant and believed it was "a sin".[2] The film received some critical attention but only had a limited release and earned just $8.4 million.[3]

Later in 1990, Eastwood directed and co-starred with Charlie Sheen in The Rookie, a buddy cop action film. Raúl Juliá and Sônia Braga play German villains engaged in a luxury car theft operation. The film, shot in San Jose, California, features an unusual female-on-male rape scene. Critics found the macho jiving between Eastwood and Sheen unconvincing and scenario improbable, and believed that many of the actors were miscast.[4] Vincent Canby of The New York Times described the film as "astonishingly empty" while Glenn Lovell of the San Jose Mercury News strongly criticized what he called "blatant racial stereotyping" of the Hispanic car thieves, the Puerto Rican with a comic German accent, and the Brazilian sex kitten bodyguard.[5] Released in December of that year, the film was a commercial success, earning $43 million at the U.S. box office.[3] 1991 was only the third year in Eastwood's career where he did not have a film showing in the cinemas.[6] The reason was an ongoing lawsuit filed by Stacy McLaughlin; Eastwood had rammed her car while backing out of his parking space in the Malpaso parking lot.[7] Eastwood won the suit, and agreed to pay McLaughlin's court fees if she agreed not to appeal.[6]

In 1992, Eastwood revisited the western genre in the self-directed film Unforgiven, where he played an aging ex-gunfighter long past his prime. The film was written by David Webb Peoples, who had written the Oscar-nominated film The Day After Trinity and co-wrote Blade Runner.[6] The concept for the film dated as far back as 1976 under the titles The Cut-Whore Killings and The William Munny Killings.[6] The project was delayed, partly because Eastwood wanted to wait until he was old enough to play his character and to savor it as the last of his western films.[6] The film also starred Gene Hackman, Morgan Freeman, and Richard Harris and then-girlfriend Frances Fisher. By re-envisioning established genre conventions in a more ambiguous and unromantic light, the picture laid the groundwork for later westerns such as Deadwood. Much of the cinematography for the film was shot in Alberta in August 1991 by director of photography Jack Green.[8] Production designer Henry Bumstead, who had worked with Eastwood on High Plains Drifter, was hired to create the "drained, wintry look" of the western.[8]

Unforgiven was a great success at the box office and critically. Its earnings of over $15 million on its opening weekend was the best ever opening for an Eastwood film.[9] It eventually earned $101 million in North American ticket sales.[10] The film was hailed by many critics as one of the best of 1992. Jack Methews of the Los Angeles Times described it as "The finest classical western to come along since perhaps John Ford's 1956 The Searchers.[9] Richard Corliss in Time wrote that the film was "Eastwood's meditation on age, repute, courage, heroism—on all those burdens he has been carrying with such grace for decades".[9] The film was nominated for nine Academy Awards,[11] including Best Actor for Eastwood and Best Original Screenplay for David Webb Peoples. It won four, including Best Picture and Best Director for Eastwood. Eastwood also garnered the Best Director Award from the National Society of Film Critics.[12] As of 2012, Unforgiven is the last of Eastwood's westerns.

In 1993, Eastwood played Frank Horrigan, a guilt-ridden Secret Service agent in the CIA thriller In the Line of Fire, co-starring John Malkovich and Rene Russo and directed by Wolfgang Petersen. Eastwood's character, Horrigan, is haunted by his failure to react in time to save John F. Kennedy's life.[13] Eastwood first received the script in the spring of 1992 and remarked that "Its almost as if it's written for me".[14] As of 2012, it is the last time he acted in a film he did not direct himself. The film was among the top 10 box office performers in that year, earning $102 million in North American ticket sales.[15] Later in 1993, Eastwood directed and co-starred with Kevin Costner in A Perfect World. Set in the 1960s, similar to Lonely Are the Brave, it relates the story of a doomed character pursued by state police using modern transportation and communication.[16] It grossed $31 million in North American box office receipts, with an overseas gross of over $100 million, making it a financial success. The film received largely positive reviews, although some critics believed that the film, at 138 minutes, was too long. Janet Maslin of The New York Times remarked that the film was the highest point of Eastwood's directing career: "It gives real meaning to the subject of men's legacies to their children".[17][18] It has an 85% score on Rotten Tomatoes.[19] In the years since its release, the film has been acclaimed by critics as one of Eastwood's most underrated directorial achievements.[20] Cahiers du cinéma selected A Perfect World as the best film of 1993.

In May 1994, Eastwood attended the 1994 Cannes Film Festival and was presented with France's medal of Comandeur de L' Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Jeanne Moreau commented, "Its remarkable that a man so important in European cinema has found the time to come here and spend twelve days watching movies with us".[21] On the jury at Cannes that year were two people very familiar to Eastwood: Catherine Deneuve, with whom he had an affair back in the mid-1960s, and Lalo Schifrin, who had composed most of the jazz tracks to his Dirty Harry films.[21]

Eastwood continued to expand his repertoire by playing opposite Meryl Streep in the love story The Bridges of Madison County (1995). Based on a best-selling novel by Robert James Waller,[22] it relates the story of Robert Kincaid (Eastwood), a photographer working for National Geographic, who has a love affair with a middle-aged Italian farm wife in Iowa named Francesca (Streep). Eastwood and Streep got along famously during production and such was their on-screen chemistry that a number of people believed that the two were having an affair off-camera, although this was denied by both.[23] The film was a hit at the box office and grossed $71 million in North America.[24] The film, unlike the novel, surprised film critics and was warmly received. Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote that Clint had managed to create "a moving, elegiac love story at the heart of Mr. Waller's self-congratulatory overkill", while Joe Morgenstern of The Wall Street Journal described The Bridges of Madison County as "one of the most pleasurable films in recent memory".[24] Eastwood then directed and starred in the well-received political thriller Absolute Power. The film's ensemble cast featured Gene Hackman, Ed Harris, Laura Linney, Scott Glenn, Dennis Haysbert, Judy Davis, and E. G. Marshall. Eastwood played a veteran thief who witnesses the Secret Service cover up a murder the President was responsible for.

"The roles that Eastwood has played, and the films that he has directed, cannot be disentangled from the nature of the American culture of the last quarter century, its fantasites and its realities."

Edward Gallafent, author, commenting on Eastwood's impact on film from the 1970s to 1990s.[25]

Eastwood directed Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, which starred John Cusack, Kevin Spacey, and Jude Law, based on the novel by John Berendt. Several changes were made from the book. Many of the more colorful characters were eliminated or made into composite characters. The reporter, played by John Cusack, was based upon Berendt, but was given a love interest not featured in the book, played by Eastwood's daughter, Alison Eastwood. The multiple Williams trials were combined into one on-screen trial. Jim Williams's real life attorney, Sonny Seiler, appeared in the film in the role of Judge White, the presiding judge at the trial. The film received a mixed response from critics. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times wrote, "I enjoyed the movie at a certain level simply as illustration: I was curious to see the Lady Chablis, and the famous old Mercer House where the murders took place, and the Spanish moss. But the movie never reaches takeoff speed; its energy was dissipated by being filtered through the deadpan character of Kelso."[26]

In 1999, Eastwood directed True Crime. Clint Eastwood plays Steve Everett, a journalist recovering from alcoholism, given the task of covering the execution of murderer Frank Beechum (played by Isaiah Washington). Everett discovers that Beechum might be innocent, but has only a few hours to prove it and save Beechum's life. The film was a box office bomb domestically, easily his worst performing film of the 1990s.[27] It had an opening weekend gross of $5,276,109 in the United States and grossed $16,649,768 total domestically, out of a budget of $55 million. It received mixed reactions from critics, with a score of 51% on Rotten Tomatoes. James Berardinelli wrote, "True Crime has the potential to be a truly memorable film, and, for more than three-quarters of its running time, it is poised to live up to that potential. But then there are the final twenty minutes, which proffer the almost-painful experience of watching compelling drama devolve into mindless action. True Crime's denouement is perplexing and exasperating, because, aside from generating some artificial tension, it contributes nothing to the story as a whole, and, consequently, serves only to cheapen it."[28]

References

- ↑ McGilligan, p.452

- ↑ McGilligan, p.454

- 1 2 McGilligan, p.461

- ↑ Schickel, p.450

- ↑ McGilligan, p.460

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGilligan, p.467

- ↑ McGilligan, p.466

- 1 2 McGilligan, p.469

- 1 2 3 McGilligan, p.473

- ↑ McGilligan, p.476

- ↑ McGilligan, p.475

- ↑ McGilligan, p.474

- ↑ Schickel, p.471

- ↑ Schickel, p.475

- ↑ McGilligan, p.480

- ↑ McGilligan, p.481

- ↑ McGilligan, p.485-6

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (November 24, 1993). "A Perfect World; Where Destiny Is Sad and Scars Never Heal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.

- ↑ "A Perfect World (1993)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Hinson, Hall (November 24, 1993). "'A Perfect World' by Hal Hinson". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.

- 1 2 McGilligan, p.491

- ↑ McGilligan, p.492

- ↑ McGilligan, p.499

- 1 2 McGilligan, p.503

- ↑ Gallafent, p.10

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (November 21, 1997). "Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2009.

- ↑ McGilligan, p.539

- ↑ Berardinelli, James. "True Crime". Reel Views. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010.