Columbia (name)

"Columbia" (/kəˈlʌmbiə/; kə-LUM-bee-ə) is a historical and poetic name used for the United States of America and also as one of the names of its female personification. It has given rise to the names of many persons, places, objects, institutions, and companies; e.g., Columbia University, the District of Columbia (the national capital), and the ship Columbia Rediviva, which would give its name to the Columbia River. Images of the Statue of Liberty largely displaced Columbia as the female symbol of the U.S. by around 1920.[1]

Columbia is a New Latin toponym, in use since the 1730s for the Thirteen Colonies. It originated from the name of Christopher Columbus and from the ending -ia, common in Latin names of countries (paralleling Britannia, Gallia etc.).

History

%2C_by_Thomas_Nast.png)

%2C_by_Thomas_Nast.jpg)

%2C_by_Thomas_Nast.jpg)

-%240.15-Fr.1269.jpg)

Massachusetts Chief Justice Samuel Sewall used the name Columbina (not Columbia) for the New World in 1697.[4] The name Columbia for "America" first appeared in 1738[5][6] in the weekly publication of the debates of the British Parliament in Edward Cave's The Gentleman's Magazine. Publication of Parliamentary debates was technically illegal, so the debates were issued under the thin disguise of Reports of the Debates of the Senate of Lilliput, and fictitious names were used for most individuals and placenames found in the record. Most of these were transparent anagrams or similar distortions of the real names; some few were taken directly from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels; and a few others were classical or neoclassical in style. Such were Ierne for Ireland, Iberia for Spain, Noveborac for New York (from Eboracum, the Roman name for York), and Columbia for America—at the time used in the sense of "European colonies in the New World".[7]

The name was perhaps first coined by Samuel Johnson, thought to have been the author of an introductory essay (in which "Columbia" already appears) which explained the conceit of substituting "Lilliputian" for English names; Johnson also wrote down the Debates from 1740 to 1743. The name continued to appear in The Gentleman's Magazine until December 1746. Columbia is an obvious calque on America, substituting the base of the surname of the discoverer Christopher Columbus for the base of the given name of the somewhat less well-known Americus Vespucius.

As the debates of Parliament, many of whose decisions directly affected the colonies, were distributed and closely followed in the British colonies in America, the name "Columbia" would have been familiar to the United States' founding generation.

In the second half of the 18th century, the American colonists were beginning to acquire a sense of having an identity distinct from that of their British cousins on the other side of the ocean. At that time, it was common for European countries to use a Latin name in formal or poetical contexts to confer an additional degree of respectability on the country concerned.[8] In many cases, these nations were personified as pseudo-classical goddesses named with these Latin names. Located on a continent unknown to and unnamed by the Romans, "Columbia" was the closest that the Americans could come to emulating this custom.

By the time of the Revolution, the name Columbia had lost the comic overtone of its "Lilliputian" origins and had become established as an alternative, or poetic name for America. While the name America is necessarily scanned with four syllables, according to 18th-century rules of English versification Columbia was normally scanned with three, which is often more metrically convenient. The name appears, for instance, in a collection of complimentary poems written by Harvard graduates in 1761, on the occasion of the marriage and coronation of King George III.[9]

- Behold, Britannia! in thy favour'd Isle;

- At distance, thou, Columbia! view thy Prince,

- For ancestors renowned, for virtues more;[10]

The name "Columbia" rapidly came to be applied to a variety of items reflecting American identity. A ship built in Massachusetts in 1773, received the name Columbia; it later became famous as an exploring ship, and lent its name to new "Columbias."

No serious consideration was given to using the name Columbia as an official name for the independent United States, but with independence the name became popular and was given to many counties, townships, and towns, as well as other institutions, e.g.:

- In 1784, the former King's College in New York City had its name changed to Columbia College, which became the nucleus of the present-day Columbia University.

- In 1786, South Carolina gave the name "Columbia" to its new capital city. Columbia is also the name of at least nineteen other towns in the United States.

- In 1791, three commissioners appointed by President Washington named the area destined for the seat of the U.S. government "the Territory of Columbia"; it was subsequently (1801) organized as the District of Columbia.

- In 1792, the Columbia Rediviva sailing ship gave its name to the Columbia River in the American Northwest (much later, the Rediviva would give its name to the Space Shuttle Columbia)

- In 1798, Joseph Hopkinson wrote lyrics for Philip Phile's 1789 inaugural "President's March" under the new title of "Hail, Columbia." Once used as de facto national anthem of the United States, it is now used as the entrance march of the Vice President of the United States.

- In 1865 Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon, the spacecraft to the moon was fired from a giant Columbiad cannon.

In part, the more frequent usage of the name Columbia reflected a rising American neoclassicism, exemplified in the tendency to use Roman terms and symbols. The selection of the eagle as the national bird, the use of the term Senate to describe the upper house of Congress, and the naming of Capitol Hill and the Capitol building were all conscious evocations of Roman precedents.

The adjective Columbian has been used to mean "of or from the United States of America", for instance in the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago, Illinois. Occasionally proposed as an alternative word for "American".

Early in World War I (1914–1918) the image of Columbia standing over a kneeling "Doughboy" was issued in lieu of the Purple Heart Medal. She gave "to her son the accolade of the new chivalry of humanity" for injuries sustained in "the" World War.

Columbian should not be confused with the adjective "Pre-Columbian", referring to a time period before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492.

In World War I the name "Liberty Bond" for savings bonds was heavily publicized, often with images from the Statue of Liberty. The personification of Columbia fell out of use, and she was largely replaced by Lady Liberty as a feminine symbol of the United States.[11] When Columbia Pictures adopted Columbia as its logo in 1924, she appeared (and still appears) bearing a torch—similar to the Statue of Liberty, and unlike 19th-century depictions of Columbia.

Personification

As a quasi-mythical figure, Columbia first appears in the poetry of African-American Phillis Wheatley starting in 1776 during the revolutionary war:

- One century scarce perform'd its destined round,

- When Gallic powers Columbia's fury found;

- And so may you, whoever dares disgrace

- The land of freedom's heaven-defended race!

- Fix'd are the eyes of nations on the scales,

- For in their hopes Columbia's arm prevails.[12]

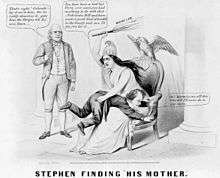

Especially in the 19th century, Columbia would be visualized as a goddess-like female national personification of the United States and of Liberty itself, comparable to the British Britannia, the Italian Italia Turrita, and the French Marianne, often seen in political cartoons of the 19th-early 20th century. This personification was sometimes called "Lady Columbia" or "Miss Columbia". Such iconography usually personified America in the form of an Indian queen or Native American princess[13]

The image of the personified Columbia was never fixed, but she was most often presented as a woman between youth and middle age, wearing classically draped garments decorated with the stars and stripes; a popular version gave her a red-and-white striped dress and a blue blouse, shawl, or sash spangled with white stars. Her headdress varied; sometimes it included feathers reminiscent of a Native American headdress, sometimes it was a laurel wreath, but most often it was a cap of liberty.

Statues of the personified Columbia may be found in the following places:

- The 1863 Statue of Freedom atop the United States Capitol building, though not actually called "Columbia", shares many of her iconic characteristics.[14][15]

- Atop Philadelphia's Memorial Hall, built 1876

- The replica Statue of the Republic ("Golden Lady") in Chicago's Jackson Park is often understood to be Columbia. It is one of the remaining icons of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

- In the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, dedicated 1949.

Modern appearances

Since 1800, the name Columbia has been used for a wide variety of items:

- Columbia University, an Ivy League university in New York City, which first adopted the name 'Columbia College' in 1784.

- The song Hail, Columbia, an American patriotic song. It was considered, with several other songs, one of the unofficial national anthems of the United States until 1931, when "The Star-Spangled Banner" was officially named the national anthem

- The song "Columbia, Gem of the Ocean" (1843) commemorates the United States under the name Columbia.

- Columbia Records, founded in 1888, took its name from its headquarters in the District of Columbia.

- Columbia Pictures, named in 1924, uses a version of the personified Columbia as its logo after a great deal of experimentation.[16]

- CBS's former legal name was the Columbia Broadcasting System, first used in 1928. The name derived from an investor, the Columbia Phonograph Manufacturing Company, owner of Columbia Records.

- The Command Module of the Apollo 11 spacecraft, the first manned mission to land on the Moon, was called Columbia (1969).

- The Space Shuttle Columbia, built 1975–1979, was named for the exploring ship Columbia.

- A personified Columbia appears in Uncle Sam, a graphic novel about American history (1997).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columbia. |

- National personification, contains the list of personifications for various nations and territories.

- The goddess Liberty

- Goddess of Democracy

- Lady Justice

- Our Lady of Guadalupe, a similar symbol for Mexico, albeit of religious nature

- Athena

- Colombia

- Bavaria, a symbol for the German state of Bavaria (Bayern)

Notes

- ↑ Donald Dewey (2007). The Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons. NYU Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Kennedy, Robert C. (November 2001). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner, Artist: Thomas Nast". On This Day: HarpWeek. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on November 23, 2001. Retrieved November 23, 2001.

- ↑ Walfred, Michele (July 2014). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner: Two Coasts, Two Perspectives". Thomas Nast Cartoons. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ↑ Thomas J. Schlereth, "Columbia, Columbus, and Columbianism" in The Journal of American History, v. 79, no. 3 (1992), 939

- ↑ The Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 8, June 1738, p. 285

- ↑ Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Dec. 1885, pp. 159–65

- ↑ Debates in Parliament, Samuel Johnson.

- ↑ E.g. "Gallia" for France, "Helvetia" for Switzerland, "Lusitania" for Portugal, "Caledonia" for Scotland, "Hibernia" for Ireland, "Polonia" for Poland etc.

- ↑ Hoyt, Albert. The Name 'Columbia' , The New England Historical & Genealogical Register, July 1886, pp. 310–13.

- ↑ Pietas et Gratulatio Collegii Cantabrigiensis apud Novanglos, no. xxix. Boston, Green and Russell, 1761.

- ↑ David E. Nye (1996). American Technological Sublime. MIT Press. p. 266.

- ↑ Selections from Phillis Wheatley Poems and Letters

- ↑ "Origins: The Female Form as Allegory".

- ↑ "Hail Columbia". Hail Columbia. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ↑ Literata (2011). "Columbia". The Order of the White Moon Goddess Gallery. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ↑ Bernard F. Dick. The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row: Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 40–42.

References

- George R. Stewart. Names on the Land. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston (1967).