Commonwealth v. Abu-Jamal

| Commonwealth vs. Abu-Jamal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County Criminal Trial Division |

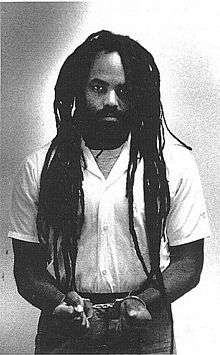

| Full case name | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook |

| Decided | July 3, 1982 |

| Transcript(s) | http://danielfaulkner.com/transcripts/ |

| Case history | |

| Subsequent action(s) | Abu-Jamal vs. Horn et al. |

| Case opinions | |

| Mumia Abu-Jamal convicted of the murder of Daniel Faulkner | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Albert F. Sabo |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Mumia Abu-Jamal was a 1982 murder trial in which Mumia Abu-Jamal was tried for the first-degree murder of police officer Daniel Faulkner. A jury convicted Abu-Jamal on all counts and sentenced him to death.

Appeal of the conviction was denied by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1989, and in the following two years the Supreme Court of the United States denied both Abu-Jamal's petition for writ of certiorari, and his petition for rehearing. Abu-Jamal pursued state post-conviction review, the outcome of which was a unanimous decision by six judges of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania that all issues raised by him, including the claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, were without merit. The Supreme Court of the United States again denied a petition for certiorari in 1999, after which Abu-Jamal pursued federal habeas corpus review.

In December 2001 Judge William H. Yohn, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania affirmed Abu-Jamal's conviction but quashed his original punishment and ordered resentencing. Both Abu-Jamal and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania appealed. On March 27, 2008, a three-judge panel in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit issued its opinion upholding the decision of the District Court.[1] In April 2009, the case was declined by the United States Supreme Court, allowing the July 1982 conviction to stand.[2]

On December 7, 2011, District Attorney of Philadelphia R. Seth Williams announced that prosecutors, with the support of the victim's family, would no longer seek the death penalty for Abu-Jamal.[3]

Figures involved

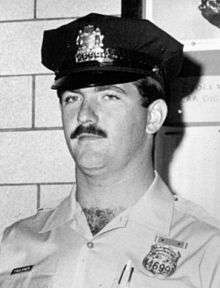

Shooting victim

Daniel J. Faulkner (December 21, 1955 – December 9, 1981): Faulkner was the youngest of seven children in an Irish Catholic family from Southwest Philadelphia. Faulkner's father, a trolley car driver, died of a heart attack when Faulkner was five. Faulkner's mother went to work and relied on her older children to help raise him. He dropped out of high school, but earned his diploma and an associate's degree in criminal justice while serving in the United States Army.[4] In 1975, Faulkner left the army, worked briefly as a corrections officer, and then joined the Philadelphia Police Department. Faulkner got married in 1979. Aspiring to attend law school and ultimately become a city prosecutor, Faulkner was enrolled in college and working toward earning a bachelor's degree in criminal justice administration when he was shot and killed.[4]

Defense

- Anthony E. Jackson – Defense counsel at the 1982 trial.

- Leonard Weinglass – Defense counsel at the 1995 hearing.

- Rachael Wolkenstein – Defense counsel at the 1995 hearing.

- Daniel R. Williams – Defense counsel at the 1995 hearing.

Prosecution

- Ed Rendell – Philadelphia District Attorney from 1977 to 1986. DA at the time in question. Philadelphia Mayor 1992–1999. PA Governor 2003–2011.

- Joseph McGill – Assistant District Attorney for the Commonwealth, prosecutor at the 1982 trial.

- Ronald D. Castille – Philadelphia District Attorney from 1986 to 1991. Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania 1993–present, (Chief Justice 2008–present).

- Lynne Abraham – Philadelphia District Attorney from 1991 to 2010. Supervised some aspects of the case.

- Charles Grant (lawyer) – Assistant District Attorney for the Commonwealth, present at the 1995 hearing.

- Arlene Fisk – Assistant District Attorney for the Commonwealth, present at the 1995 hearing.

- Linda Perkins – Assistant District Attorney for the Commonwealth, present at the 1995 hearing.

Witnesses

- Robert Chobert – Cab driver and eyewitness. Testified for the prosecution at the 1982 trial.

- Cynthia White – Prostitute and eyewitness. Testified for the prosecution at the 1982 trial.

- Michael Scanlan (witness) – Motorist and eyewitness. Testified for the prosecution at the 1982 trial.

- Albert Magilton – Pedestrian and witness of part of the events. Testified for the prosecution at the 1982 trial.

- Dessie Hightower – Testified for the defense at the 1982 trial.

- Veronica Jones – Prostitute and eyewitness. Testified for the defense at the 1982 trial.

- Joseph Grimes – Latent Print Examiner for the Identification Unit of the Philadelphia Police Department; testified at the 1982 trial.

- Priscilla Durham – Security officer at the hospital. Testified for the prosecution.

- Garry Bell (police officer) – Police officer. Testified for the prosecution.

- William "Dales" Singletary – Witness. Testified at the 1995 review hearing.

- Vernon Jones (police officer) – Police officer. Testified at the 1995 review hearing.

- Robert Harkins – Witness. Testified at the 1995 review.

- George Fassnacht – Firearms expert, testified at 1995 hearing.

- Robert Harkens (spelled Harkins in the transcript) – cab-driver, eyewitness for the defense at the 1995 hearing.

Other figures

- William Cook – Abu-Jamal's younger brother, street vendor. His VW Beetle was stopped by Faulkner on the night in question.

- Deborah Kordansky – Potential witness for the defense. Refused to come to court.

- Kenneth Freeman (W. Cook's partner) – Friend and business partner to William Cook.

- George Michael Newman – Private investigator. Claimed Chobert had recanted his testimony.

- Arnold Beverly – Claimed in 1999 to have been hired by the mob to assassinate Faulkner on the night in question.

- Gary Wakshul – Police officer who accompanied Abu-Jamal to and at the hospital.

- Arnold Howard – Close friend of Abu-Jamal. His duplicate driver's license application was found on Faulkner's person on the night in question.

- Terri Maurer-Carter – Court stenographer for 1982 trial. In 2001, made an affidavit claiming Judge Sabo said "Yeah, and I'm going to help them fry the nigger" at the time of the 1982 trial.

- Kenneth Pate – Stepbrother of Priscilla Durham. Claimed his step sister told him she did not actually hear what she testified to hearing.

- Yvette Williams (witness) – In police custody with Cynthia White at the time of the incident.

- Pamela Jenkins (witness) – Prostitute, police informant. Made a statement in 1997.

Timeline

- 1981, December 9: Faulkner shot and killed.

- 1982, June 17 – July 3: Trial of Mumia Abu-Jamal. Convicted and sentenced to death.

- 1989, March 6: Supreme Court of Pennsylvania considers and denies the appeal of the sentence.

- 1990, October 1: Supreme Court of the United States denies petition for writ of certiorari.

- 1995, June 1: Death warrant signed by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge. Suspended pending review.

- 1995–6: Post-conviction review hearings.

- 1998: Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled unanimously that all issues were without merit.

- 1999, October 4: Supreme Court of the United States denied a petition for certiorari against that decision.

- 1999, October 13: Second death warrant signed by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge. It was stayed while Abu-Jamal sought habeas corpus review.

- 2001, December 18: United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania upheld the conviction but voided the sentence of death. Both parties appealed.

- 2005, December 6: U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit admitted four issues for appeal of the ruling of the District Court.

- 2008, March 27: Third Circuit Court upholds decision of the District Court by a 2–1 majority.

- 2008, July 22: Third Circuit Court denies petition to rehear.

- 2009, April 6: United States Supreme Court denies petition to rehear.

1982 trial

On December 9, 1981, around 3:51 a.m. near the intersection of 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia, Philadelphia Police Department officer Daniel Faulkner was conducting a traffic stop of William Cook, Abu-Jamal's younger brother. Faulkner and Cook became engaged in a physical confrontation.[5] Abu-Jamal's taxi was parked across the street, from which he ran towards Cook's car and shot Faulkner in the back and then in the face. During the encounter, Faulkner shot Abu-Jamal in the stomach. Faulkner died at the scene from the head shot. Police arrived and arrested Abu-Jamal, who was wearing a shoulder holster. His revolver was beside him and had five spent cartridges. Abu-Jamal was taken directly from the scene of the shooting to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, where he received treatment for his wound. He was charged with the first-degree murder of Daniel Faulkner, and initially retained the services of criminal defense attorney Anthony Jackson.[6]

The case went to trial in June 1982 at Philadelphia's City Hall. Judge Albert F. Sabo initially agreed to Abu-Jamal's request to represent himself, with Jackson acting as his legal advisor. During the first day of the trial, however, this decision was reversed and Jackson was ordered to resume acting as Abu-Jamal's sole advocate by reason of what the judge deemed to be intentionally disruptive actions by Abu-Jamal,[7] for which he was removed from the courtroom at least 13 times during the course of the legal proceedings and trial.[8]

The jury was initially composed of nine white and three black jurors, after McGill used 11 of 15 peremptory challenges to remove blacks from the jury pool. Another black juror was later removed by Sabo, leaving two black jurors out of twelve hearing the case.[9]

Prosecution case

The prosecution maintained that:[6]

- During the traffic stop, Cook assaulted Faulkner, who in turn attempted to subdue Cook.

- Abu-Jamal emerged from a nearby parking lot, crossed the street, and shot Faulkner in the back.

- Faulkner was able to return fire, seriously wounding Abu-Jamal.

- Abu-Jamal then advanced on Faulkner and fired additional shots at close range, one of which struck Faulkner in the face causing his death.

- Abu-Jamal was unable to flee due to his own gunshot wound, collapsed on a nearby curb, and was taken into custody by other police officers who had been summoned by Faulkner at the time of the traffic stop.

Eyewitnesses

The four prosecution eyewitnesses were:

- Robert Chobert, a cab driver

- Cynthia White, a prostitute.

- Michael Scanlan, a motorist.

- Albert Magilton, a pedestrian.

Robert Chobert said he was in his cab parked directly behind Faulkner's police car. He positively identified Abu-Jamal as the shooter, testifying: "I heard a shot. I looked up, I saw the cop fall to the ground, and then I saw Jamal standing over him and firing some more shots into him...Then I saw him [Jamal] walking back about ten feet and he just fell by the curb."[10] During cross-examination, Chobert admitted that he had originally told the police that the shooter had moved 30 rather than 10 ft away from Faulkner, and had been 30-to-50 pounds heavier than Abu-Jamal. He explained, "I'm not good at weight. Do you think I'm going to stand there for a couple of minutes and ask him how much he weighs?"[11] Chobert was a disqualified/unlicensed cab driver on parole for arson.[12] He had two prior arrests for drunk-driving,[13] and admitted in 1995 to having sought the advice of the trial prosecutor as to how he could reclaim his driving privileges.[14]

Cynthia White testified to witnessing the shootings from a nearby corner. She said: "[Abu-Jamal] was running out of the parking lot...he shot two times at the police officer...he came on top of the police officer and shot some more times. After that he went over and he slouched down and he sat on the curb."[15] Dessie Hightower stated that he observed her to be at least half a block further away.[16] Prostitute Veronica Jones said later that she had been offered favorable treatment by police on condition that she corroborate Cynthia White.[16] Yvette Williams later claimed that while incarcerated with White in December 1981 she was told by her that she had not seen who shot Faulkner and that she had entirely fabricated a witness account identifying Abu-Jamal out of fear of the Philadelphia police.[17] Police informant Pamela Jenkins testified at a post-conviction relief hearing in 1997, that she had been pressured by Philadelphia police to falsely state that she had witnessed the killing of Faulkner and identify Abu-Jamal as the murderer. She also testified that she thought White was in fear of her life from police after the shooting of Faulkner, and that she had seen Ms White in the company of Philadelphia police as recently as March 1997.[18] However, the prosecution produced Cynthia White's death certificate showing that she had died in 1992.[19]

Scanlan testified that he saw Faulkner assaulted in front of his police car shortly before another man ran across the street from a parking lot and shot Faulkner. Scanlan was not able to identify or describe the shooter. Under cross-examination, which was interrupted by Abu-Jamal being removed from the courtroom for disruption, Scanlan admitted to being mildly under the influence of alcohol.[20]

Magilton testified to witnessing Faulkner pull over Cook's car but, at the point of seeing Abu-Jamal start to cross the street toward them from the parking lot, he turned away and lost sight of what happened next until he heard gunshots. He did not see any shooting, or Chobert's vehicle parked behind Faulkner's.[21]

Hospital confession

Two witnesses, security officer Priscilla Durham and Police Officer Garry Bell, testified that while Abu-Jamal was at hospital, he acknowledged that he had shot Faulkner by proclaiming, "I shot the motherfucker, and I hope the motherfucker dies."[22] The hospital doctors have claimed that Abu-Jamal was not capable of making such a statement during that time.[23] The original report of Gary Wakshul, a police officer who accompanied Abu-Jamal to and at the hospital, relates that "the negro male made no comments".[24] Over two months afterwards, when interviewed by police Internal Affairs officers, Wakshul claimed to have remembered hearing Abu-Jamal's alleged confession. He blamed "emotional trauma" for the delay.[24] When the defense attempted to call Wakshul for cross-examination, it was reported that he was on vacation and unavailable. Wakshul never testified in court and his original statement that "the negro male made no comments" was never admitted as evidence.[24]

Physical evidence

A .38 caliber Charter Arms revolver registered to Abu-Jamal was found at the scene next to him with 5 spent shell casings.[25] Tests performed with the physical evidence verify that Faulkner was killed by a .38 caliber bullet. The extracted slugs were identified as Federal brand .38 Special +P bullets with hollow bases, which matched the shell casings in Abu-Jamal's handgun retrieved at the scene. Rifling characteristics evident on the bullet fragments extracted from Faulkner's body matched those of the handgun. Anthony L. Paul, Supervisor of the Firearms Identification Unit, testified that the type of bullet was rare at the time, with only one manufacturer, though he could name two other manufacturers which produced weapons bearing the same rifling characteristics.[26] Experts testified that the bullet taken from Abu-Jamal was fired from Faulkner's service weapon. George Fassnacht, the defense's ballistics expert, did not dispute the findings of the prosecution's experts.[27]

Amnesty International, with reference to the physical evidence, has expressed the view that "...the police failed to conduct tests to ascertain whether the weapon had been fired in the immediate past...Compounding this error, the police also failed to conduct chemical tests on Abu-Jamal's hands to find out if he had fired a gun recently."[24] In a 1995 hearing, a defense ballistics expert testified that due to Abu-Jamal's struggle with the police during his arrest, such a test would have been difficult to accomplish and, due to the gunpowder residue possibly being shaken or rubbed off, would not have been scientifically reliable.[28] A note written by coroner Dr. Paul Hoyer, who autopsied Daniel Faulkner, states that he extracted a .44 caliber bullet from Faulkner. This has led to claims that Faulkner was shot by a .44 caliber rather than a .38 caliber weapon. Hoyer admitted in 1995 that this was an "intermediate note" that was not supposed to be published, and that the note had been a "lay guess" based on his own observations, that he was not a firearms expert and that he had not received any training in weapons ballistics.[29]

Defense case

Defense witness Dessie Hightower described a man running along the street shortly after the shooting.[30] This became known as the "running man theory", based on the possibility that a "running man" may have been the actual shooter. Another witness, Veronica Jones, said "All I seen was two men and a policeman on the ground and what else can I say? I was kind of intoxicated." In reply to the question, "Did you see anyone running away from the scene?" She replied, "I didn't see anyone do nothing. No one moved."[31] The defense claimed to have a third witness, Deborah Kordansky, but she refused to appear in court.[32]

The defense presented character witnesses including poet Sonia Sanchez. Sanchez testified that Abu-Jamal was "viewed by the black community as a creative, articulate, peaceful, genial man".[33] During cross examination the prosecution raised her association with convicted felon and Black Panther activist Joanne Chesimard; Sanchez was also asked over defense objections whether she supported other blacks who had killed police, to which she replied she had.[34]

Witnesses speaking after the trial

Abu-Jamal did not state his version of the events during the initial police investigation nor did he testify in his own defense at trial. Nearly 20 years later, a man named Arnold Beverly submitted an affidavit stating that he was the person who killed Officer Faulkner. Beverly wrote that while "wearing a green (camouflage) army jacket", he had run across the street and shot Daniel Faulkner as part of a contract killing because Faulkner was interfering with graft and payoff to corrupt police.[35] Abu-Jamal subsequently provided his own statement in which he said he had been sitting in his cab across the street when he heard shouting, then saw a police vehicle, then heard the sound of gunshots. Upon seeing his brother appearing disoriented across the street, Abu-Jamal ran to him and was shot by a police officer. He maintains to have no memory of the events between being shot and the arrival of officers at the scene. He also claims been abused by the police while he was still in need of medical assistance for his wound. He explained, "At my trial I was denied the right to defend myself. I had no confidence in my court-appointed attorney, who never even asked me what happened the night I was shot and the police officer was killed; and I was excluded from at least half the trial ... Since I was denied all my rights at my trial I did not testify. I would not be used to make it look like I had a fair trial ... I never said I shot the policeman. I did not shoot the policeman ... I never said I hoped he died. I would never say something like that."[36]

For a similar period, William Cook also did not testify at the trial or make any statement about events that night other than saying to police at the crime scene: "I ain't got nothing to do with this."[37] In 2001, Cook belatedly declared that he would be willing to testify and that both he and his brother "had nothing do with shooting or killing the policeman". He stated that another man, Kenneth Freeman, was in his car at the time. According to Cook, Freeman was sitting in the front passenger seat, armed with a .38, wearing a green army jacket, knowing of a plan to kill Faulkner, and participating in the shooting.[38] Freeman's handcuffed and naked corpse was discovered in North Philadelphia on the night of the police bombing of the MOVE communal residence in 1985 and neither his name nor the fact of his presence at the crimescene was raised at any stage during the course of the trial and sentencing in 1982.[39] At the time of his death, Daniel Faulkner was in possession of the replacement temporary driver license of Arnold Howard which the latter had recently "loaned" to Freeman for unspecified purposes.[40]

Several others have made statements in support of Abu-Jamal. At a post-conviction review hearing in 1995, William "Dales" Singletary testified that he witnessed the shooting and that the gunman was the passenger in Cook's car wearing an army overcoat. Singletary said that police tore up his written statements and that he was prevailed upon to sign a different statement which they dictated.[41] Singletary's account was deemed "not credible" and "medically impossible" (he claimed that Faulkner spoke after being shot in the eye at point blank range, which would have been instantaneously lethal, and that a police helicopter was in attendance, which no other witnesses described).[27] Police officer Vernon Jones testified that at the crime scene Singletary had said that he had not witnessed any shooting other than hearing some shots that he thought were firecrackers.[42] William Harmon, who had convictions for forgery, fraud and theft by deception, testified that he had seen a man other than Abu-Jamal kill Faulkner and flee in a car which pulled up at the crimescene.[43]

Court stenographer Terri Maurer-Carter stated in a 2001 affidavit that the presiding Judge had exclaimed, "Yeah, and I'm going to help them fry the nigger", in the course of a conversation regarding Abu-Jamal's case.[44][45] Judge Sabo denied making such a comment.[46] Kenneth Pate, a stepbrother of Priscilla Durham with a history of imprisonment, swore a declaration that he asked her in a telephone conversation whether she had heard Abu-Jamal confess and that she had answered, "All I heard him say was: 'Get off me, get off me, they're trying to kill me'".[47] Pate reported the conversation to Abu-Jamal while they were serving in the same prison.[47]

In corroboration of the four prosecution eyewitnesses, Robert Harkins testified in 1995, that he had witnessed a man stand over Faulkner as the latter lay wounded on the ground, who shot him point-blank in the face and who then "walked and sat down on the curb".[48][49] In media coverage, a volunteer named Phillip Bloch claimed that he visited Abu-Jamal in prison in 1992 and asked him whether he regretted killing Faulkner, to which Abu-Jamal replied, "Yes."[50] Bloch, otherwise a supporter of Abu-Jamal's case, stated he came forward after he grew concerned about the vilification of Daniel Faulkner.[50] In response, Abu-Jamal is reported to have said "A lie is a lie, whether made today or 10 years later", and thanked the media "...not for their work but for stoking this controversy, because controversy leads to questioning, and one can only question this belated confession."[51]

Verdict, death sentence, and reactions

The jury delivered a unanimous guilty verdict after three hours of deliberations. In the sentencing phase of the trial Abu-Jamal read to the jury from a prepared statement and was then sworn and cross-examined about issues relevant to the assessment of his character by Joseph McGill, the prosecuting attorney.[52] In his statement Abu-Jamal criticized his attorney as a "legal trained lawyer" who was imposed on him against his will who "knew he was inadequate to the task and chose to follow the directions of this black-robed conspirator, [Judge] Albert Sabo, even if it meant ignoring my directions". He claimed that his rights had been "deceitfully stolen" from him by the Judge, particularly focusing on the denial of his request to receive defense assistance from John Africa (who was not an attorney) and his being prevented from proceeding pro se. He quoted remarks of John Africa and declared himself "innocent of these charges".[53]

Abu-Jamal was subsequently sentenced to death by the unanimous decision of the jury.[54] The date of the sentence is recorded as May 25, 1983.[55] Judicial execution in Pennsylvania is by means of lethal injection and would occur at the State Correctional Institution - Rockview.[56]

The Philadelphia Office of the District Attorney, Daniel Faulkner's family, including his wife Maureen, the Fraternal Order of Police, and other law-enforcement-related organizations have expressed approval of the conviction and sentence—being of a view that Abu-Jamal murdered Faulkner while the latter was making a lawful arrest in the line of police duty, and that Abu-Jamal had received a fair trial.[57] District Attorney Lynne Abraham, who at times has supervised aspects of the Abu-Jamal case, is on record stating that it was the "most open-and-shut murder case" she had ever tried, and that Abu-Jamal:

"Never produced his own brother, who was present at the time of the murder, (yet) he has offered up various individuals who would claim that one trial witness or another must have lied; or that some other individual has only recently been discovered who has special knowledge about the murder; or that someone has fallen out of the skies, who is supposedly willing to confess to the murder of Officer Faulkner."[58]

Appeals and legal developments

1983–1999 State appeals

Direct appeal of his conviction was considered and denied by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on March 6, 1989,[59] subsequently denying rehearing.[60] On October 1, 1990, the Supreme Court of the United States denied his petition for writ of certiorari,[61] and his petition for rehearing twice up to June 10, 1991.[27][62]

On June 1, 1995 his death warrant was signed by Pennsylvania Governor Tom Ridge.[27] Its execution was suspended while Abu-Jamal pursued state post-conviction review, the outcome of which was a unanimous decision by six judges of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on October 31, 1998 that all issues raised by him, including the claim of ineffective assistance of counsel, were without merit.[63] The Supreme Court of the United States denied the petition for certiorari against that decision on October 4, 1999, enabling Governor Ridge to sign a second death warrant on October 13, 1999. Its execution in turn was stayed as Abu-Jamal commenced his pursuit of federal habeas corpus review.[27]

2001 Federal ruling directing resentencing

Judge William H. Yohn Jr. of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania upheld the conviction but voided the sentence of death on December 18, 2001, citing irregularities in the original process of sentencing.[27] Particularly,

"...the jury instructions and verdict sheet in this case involved an unreasonable application of federal law. The charge and verdict form created a reasonable likelihood that the jury believed it was precluded from considering any mitigating circumstance that had not been found unanimously to exist."[27]

He ordered the State of Pennsylvania to commence new sentencing proceedings within 180 days[64] and ruled that it was unconstitutional to require that a jury's finding of circumstances mitigating against determining a sentence of death be unanimous.[65] Eliot Grossman and Marlene Kamish, attorneys for Abu-Jamal, criticized the ruling on the grounds that it denied the possibility of a trial de novo at which they could introduce evidence that their client had been the subject of a frameup.[66] Prosecutors also criticized the ruling; Maureen Faulkner described Abu-Jamal as a "remorseless, hate-filled killer" who would "be permitted to enjoy the pleasures that come from simply being alive" on the basis of the judgement.[67] Both parties appealed.

2005 Federal higher appeal

On December 6, 2005, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit admitted four issues for appeal of the ruling of the United States District Court:[68]

- in relation to sentencing, whether the jury verdict form had been flawed and the judge's instructions to the jury had been confusing;

- in relation to conviction and sentencing, whether racial bias in jury selection existed to an extent tending to produce an inherently biased jury and therefore an unfair trial (the Batson claim);

- in relation to conviction, whether the prosecutor improperly attempted to reduce jurors' sense of responsibility by telling them that a guilty verdict would be subsequently vetted and subject to appeal;

- in relation to post-conviction review hearings in 1995–6, whether the presiding Judge—who had also presided at the trial—demonstrated unacceptable bias in his conduct.

The Third Circuit Court heard oral arguments in the appeals on May 17, 2007, at the United States Courthouse in Philadelphia. The appeal panel consisted of Chief Judge Anthony Joseph Scirica, Judge Thomas Ambro, and Judge Robert Cowen. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania sought to reinstate the sentence of death, on the basis that Yohn's ruling was flawed, as he should have deferred to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court which had already ruled on the issue of sentencing, and the Batson claim was invalid because Abu-Jamal made no complaints during the original jury selection. Abu-Jamal's counsel told the Third Circuit Court that Abu-Jamal did not get a fair trial because the judge was a racist and the jury was both racially biased and misinformed.[69] On March 27, 2008, the three-judge panel issued its opinion upholding Abu-Jamal's conviction while ordering a new sentencing hearing. Should the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania choose not to hold a new hearing, Abu-Jamal will be automatically sentenced to life in prison.[1] On July 7, 2008, appellate counsel petitioned the court for rehearing en banc, seeking reconsideration of the decision by the full Third Circuit panel of 12 judges. The petition was denied on July 22, 2008,[70] and on April 6, 2009, the United States Supreme Court also refused to hear Abu-Jamal's appeal, letting the 1982 conviction stand.[2] On January 19, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the appeals court to reconsider its decision to rescind the death sentence.[71]

2011 Death penalty dropped

On December 7, 2011, District Attorney of Philadelphia R. Seth Williams announced that prosecutors, with the support of the victim's family, would no longer seek the death penalty for Abu-Jamal.[3][72] Faulkner had indicated she did not wish to relive the trauma of another trial, and that it would be extremely difficult to present the case against Abu-Jamal again, after the passage of 30 years and the deaths of several key witnesses. Williams, the prosecutor, said that Abu-Jamal will spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole,[73] a sentence that was reaffirmed by the Superior Court of Pennsylvania on July 9, 2013.[74] After the press conference, Maureen Faulkner made an emotional statement condemning Abu-Jamal.[75]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Mumia Abu-Jamal v. Horn et al." (pdf). U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. March 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- 1 2 "Supreme Court lets Mumia Abu-Jamal's conviction stand". CNN. April 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- 1 2 "Death Penalty Dropped Against Mumia Abu-Jamal". Associated Press. NPR. December 7, 2011.

- 1 2 "The Danny Faulkner Story". Fraternal Order of Police. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ Wisenberg Brin, Dinah (2 July 1995). "Death-Row Clock Ticking for Activist Convicted of Killing Officer". Los Angelos Times. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Trial and Post-Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) hearing transcripts" (pdf). Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §1.72–§1.73". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 17, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "danielfaulkner.com summary of case facts (p. 2)" (pdf). Justice for P/O Daniel Faulkner. 1998. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Lindorff, Dave (7 December 2006). "Mumia Abu-Jamal Case Goes to Third Circuit". Counterpunch. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §3.210–§3.211". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 19, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §3.235–§3.247". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 19, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §3.216". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 19, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript §3.226". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 19, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp. 5–6". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 15, 1995. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp. 94–95". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 21, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- 1 2 Mumia Abu-Jamal (1997). Mumia Abu-Jamal: A Case for Reasonable Doubt? (DVD of HBO TV Special). London, UK: Otmoor Productions.

- ↑ Williams, Yvette (January 28, 2002). "Declaration of Yvette Williams". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing testimony of Pamela Jenkins.". Commonwealth v Mumia Abu-Jamal, Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. June 26, 1997. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript p.144". Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. June 26, 1997. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp. 5–75". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 25, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.75 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 25, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp.29, 31, 34, 137, 162 and 164". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 24, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Smith, Laura (October 27, 2007). "'I spend my days preparing for life, not for death'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Life in the Balance: The Case of Mumia Abu-Jamal". Amnesty International. February 17, 2000. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Developments in the Mumia Abu-Jamal case". CNN.com. December 18, 2001. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.169". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 23, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Yohn, William H., Jr. (December 2001). "Memorandum and Order" (pdf). Mumia Abu-Jamal, Petitioner, vs. Martin Horn, Commissioner, Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, et al., Respondents. US District Court for the Eastern District of Philadelphia. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript, pp. 118–122". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 2, 1995. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp. 191–192". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 9, 1995. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.127". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 28, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp. 99–100". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 29, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Post-Trial Motions transcript p.29". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. May 25, 1983. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ↑ "Trial transcript p.19". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 30, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ "Trial transcript pp. 19–30". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, Philadelphia County, Criminal Trial Division. June 30, 1982. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ↑ Beverly, Arnold (June 8, 1999). "Affidavit of Arnold Beverly". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Abu-Jamal, Mumia (May 3, 2001). "Declaration of Mumia Abu-Jamal". Chicago Committee to Free Mumia Abu-Jamal. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Lopez, Steve (July 23, 2000). "Wrong Guy, Good Cause". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Cook, William (April 29, 2001). "Declaration of William Cook". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Jurors Never Saw Earliest Photos at Abu-Jamal's 1982 Trial" (Press release). Educators for Mumia Abu-Jamal. September 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Asher, Robert; Goodheart, Lawrence B.; Rogers, Alan (2005). Murder on Trial: 1620–2002. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-7914-6378-8.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.204 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 11, 1995. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.16 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 14, 1995. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript pp.45 ff.". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trial Division. August 10, 1995. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Maurer-Carter, Terri (August 21, 2001). "Declaration of Terri Maurer-Carter". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Bryan, Robert R.; Judith L. Ritter (July 20, 2006). "Brief on behalf of Mumia Abu-Jamal to the US Court of Appeal" (PDF). Law Offices of Robert R. Bryan. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Conroy, Theresa (September 4, 2001). "She's 'scared' by impact of her allegation – Says Mumia judge made a racist remark". Philadelphia Daily News.

- 1 2 Pate, Kenneth (April 18, 2003). "Declaration of Kenneth Pate". Free Mumia Coalition. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "PCRA hearing transcript". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of the Common Pleas, First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, Criminal Trials Division. August 2, 1995. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Faulkner, Maureen (December 8–14, 1999). "Running From The Truth". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- 1 2 Bissinger, Buzz (August 1999). "The Famous And The Dead" (PDF). Vanity Fair. pp. 6 and 13. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Mackler, Jeff (August 1999). "Vanity Fair and ABC-TV Stories of Mumia's 'Confession' Collapse". Socialist Action (US). Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp. 3–34". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Please, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp. 10–16". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Please, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Trial transcript, pp. 100–103". Commonwealth vs. Mumia Abu-Jamal aka Wesley Cook. Court of Common Please, Philadelphia Criminal Trial Division. July 3, 1982. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (November 1, 2007). "Persons Sentenced to Execution in Pennsylvania as of November 1, 2007" (pdf). Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "History". Pennsylvania Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ "Justice for Daniel Faulkner". 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Saunders, Debra J. (December 21, 2001). "Mumia finds safety in numbers". Jewish World Review. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 555 A.2d 846 (1989).

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 569 A.2d 915 (1990).

- ↑ Abu-Jamal v. Pennsylvania, 498 U.S. 881 (1990).

- ↑ Abu-Jamal v. Pennsylvania, 501 U.S. 1214 (1991).

- ↑ Pennsylvania v. Abu-Jamal, 720 A.2d 79 (1998).

- ↑ "Abu-Jamal's death sentence overturned". BBC News. December 18, 2001. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ See p.70 of the July 2006 appeal brief for Mumia Abu-Jamal before the US Court of Appeal citing the ruling of Judge Yohn in the US District Court, the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and the United States Supreme Court precedent of Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367 (1988)

- ↑ Piette, Betsey (March 6, 2003). "Mumia still waiting for due process". International Concerned Family and Friends of Mumia Abu-Jamal. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Rimer, Sara (December 19, 2001). "Death sentence overturned in 1981 killing of officer". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ Lindorff, Dave (December 8, 2005). "A victory for Mumia". Salon.com. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Duffy, Shannon P. (May 18, 2007). "Spectators Pack Courtroom as 3rd Circuit Hears Appeal in Mumia Abu-Jamal Case". The Legal Intelligencer. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Sur Petition for Rehearing Abu-Jamal v. Horn et al." (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. July 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

- ↑ "U.S. court sends back Abu-Jamal death penalty case". Reuters.com. January 19, 2010.

- ↑ "D.A.: Abu-Jamal can go rot in cell". philly.com. December 8, 2011.

- ↑ Williams, Timothy (December 7, 2011). "Execution Case Dropped Against Abu-Jamal". New York Times. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ Decision of Appeal upon Judgment of Sentence in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v Mumia Abu-Jamal, Superior Court of Pennsylvania (July 9, 2013)

- ↑ "Widow's Message to Mumia Abu-Jamal". NBC News. December 7, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

Coordinates: 39°56′52″N 75°09′44″W / 39.94783°N 75.16211°W