Corruption in Malaysia

| Political corruption |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

| Corruption by country |

| Europe |

| Asia |

| Africa |

| North America |

| South America |

| Oceania and the Pacific |

| Transcontinental countries |

According to a 2013 public survey in Malaysia by Transparency International, a majority of the surveyed households perceived Malaysian political parties to be highly corrupt.[1] A quarter of the surveyed households consider the government's efforts in the fight against corruption to be ineffective.[1]

Business executives surveyed in the World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report 2013-2014 reveal that unethical behaviours of companies constitute a disadvantage for doing business in Malaysia.[2] Government contracts are sometimes awarded to well-connected companies, and the policies of awarding huge infrastructure projects to selected Bumiputera companies without open tender continue to exist.[3]

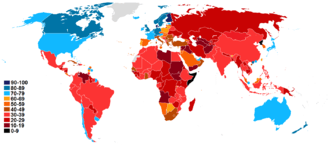

Corruption Perceptions Index

Corruption is a problem. Malaysia had a corruption score of 52 out of 100 (high scores are less corrupt); this makes Malaysia the 2nd "cleanest" country in SE Asia, 9th out of 28 in APAC and 50th of the 175 countries assessed worldwide.

Transparency International list Malaysia's key corruption challenges as:

- Political and Campaign Financing: Donations (e.g.: USD700Million) from both corporations and individuals to political parties and candidates are not limited in Malaysia. Political parties are also not legally required to report on what funds are spent during election campaigns. Due in part to this political landscape, Malaysia’s ruling party for over 55 years has funds highly disproportionate to other parties. This unfairly impacts campaigns in federal and state elections and can disrupt the overall functioning of a democratic political system.

- “Revolving door”: Individuals regularly switch back and forth between working for both the private and public sectors in Malaysia. Such circumstances – known as the ‘revolving door’ – allow for active government participation in the economy and public-private relations to become elusive. The risk of corruption is high and regulating public-private interactions becomes difficult, also allowing for corruption to take place with impunity. Another factor which highlights the extent of ambiguity between the public sector and private corporate ownership is that Malaysia is also a rare example of a country where political parties are not restricted in possessing corporate enterprises.

- Access to information: As of April 2013, no federal Freedom of Information Act exists in Malaysia. Although, Selangor and Penang are the only Malaysian states out of thirteen to pass freedom of information legislation, the legislation still suffers from limitations. Should a federal freedom of information act be drafted it would conflict with the Official Secrets Act – in which any document can be officially classified as secret, making it exempt from public access and free from judicial review. Additional laws such as the Printing Presses and Publications Act, the Sedition Act 1949 (subsequently replaced with the National Harmony Act), and the Internal Security Act 1969 also ban the dissemination of official information and offenders can face fines or imprisonment.TI).[4] Malaysia suffers from corporate fraud in the form of intellectual property theft.[5] Counterfeit production of several goods including IT products, automobile parts, etc., are prevalent.[5]

In 2013, Malaysia was identified in a survey by Ernst and Young as one of the most corrupt countries in the region according to the perceptions of foreign business leaders, along with neighbouring countries and China. The survey asked whether it was likely that each country would take shortcuts to achieve economic targets.[6]

Anti-corruption bodies

Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission

The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) (Malay: Suruhanjaya Pencegahan Rasuah Malaysia, (SPRM)) (formerly Anti-Corruption Agency (ACA) or Badan Pencegah Rasuah (BPR)) is a government agency in Malaysia that investigates and prosecutes corruption in the public and private sectors. The MACC was modelled after top anti-corruption agencies, such as the Hong Kong's Independent Commission Against Corruption and the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption, Australia.[7]

The MACC is currently headed by Chief Commissioner Datuk Abu Kassim Bin Mohamed. He was appointed in January 2010 to replace former Chief Commissioner Datuk Seri Ahmad Said Bin Hamdan. Similarly, the agency is currently under the Prime Minister's Department.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Global Corruption Barometer 2013". Transparency International. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Global Competitiveness Report 2013-2014". The World Economic Forum. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysia Country Profile". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Darryl S. L. Jarvis (2003). International Business Risk: A Handbook for the Asia-Pacific Region. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 0-521-82194-0.

- 1 2 Darryl S. L. Jarvis (2003). International Business Risk: A Handbook for the Asia-Pacific Region. Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0-521-82194-0.

- ↑ http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/malaysia-one-of-the-most-corrupt-nations-survey-shows

- 1 2 "Government Directory: Prime Minister's Department". Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

External links