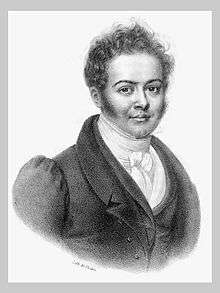

Cyrille Bissette

Cyrille Bissette or in English also Cyril Bissette (1795–1858) was a free person of color (homme de couleur) from Martinique who was a radical abolitionist.[1] He served in the French National Assembly from 1848 to 1851.

Life

Bissette was born July 9, 1795 in Fort Royal (now Fort-de-France), Martinique. In the racial categorization of the time, he was considered a mulatto.[2] He was said to be related to Josephine, the wife of Napoleon I.[3] Sources vary on the exact family relationship: he may have been the child of an illegitimate son of Joseph Tascher de la Pagerie, Josephine's father,[4] or his mother may have been the illegitimate daughter of a member of the Tascher de la Pagerie family.[5]

Bissette was a merchant and a slaveholder early in his career, but became radicalized by his own arrest and sentencing for rights advocacy, a controversy that became known as l'affaire Bissette.[6]

Bissette died in Paris January 22, 1858.

Political activities

Bissette was a leader of efforts to abolish slavery in the French Colonies. He was involved in the so-called "Bissette affaire," whose anti-slavery activities begin to be radicalized about this time.

The aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars jeopardized the status of freed slaves and free persons of color in the French colonies. Some Black men and mulattos had been manumitted in order to serve in the militia in the first decade of the 19th century. But men of color later might find themselves impressed into service or re-enslaved because they failed to prove their status to the satisfaction of current authorities attempting to reinstate the former colonial regime. In 1822, these circumstances led to a slave revolt in Martinique, and in turn to stricter "security measures" that affected both free persons of color as well as those who had been questionably enslaved.[7] The homes of free people were searched for anti-slavery materials.[8] Bissette was one of three free men of color who were arrested during the crackdown for possessing a political pamphlet agitating against the loss of rights for their people.[9]

Following their conviction in 1824, Bissette and his two friends had their property confiscated, were sentenced to life as a galley slave, and were branded with the letters GAL[10] They were then deported to Paris.[11] The savagery of the sentence shocked liberal sensibilities in the metropolis, and the case became a cause célèbre.[12] The legal case continued in the courts until 1827, when a final verdict exculpated the participants other than Bissette.[13] A campaign of support eventually obtained his pardon and release from prison.[14]

Bissette was a leading figure throughout the 1840s in the movement that led to France abolishing slavery in 1848.[15] But while active in the cause of abolition, Bissette did not belong to the Société pour l'Abolition de l'Esclavage (Society for the Abolition of Slavery), perhaps because he felt unwelcome or because he could not afford the subscription fee that the society's wealthy members paid.[16] He was barred from testifying before the Parliamentary Commission on Emancipation, evidently because of his color.[17]

In August 1848, Bissette was one of two men of color elected to represent the Caribbean colonies in the French Parliament.[18] The French colonies were given representation in the National Assembly by the French Constitution of 1848, on the principle of universal suffrage (which in fact excluded women). Bissette represented Martinique.[19] The mulatto artillery officer François Perrinon represented Guadeloupe.[20]

Literary activities

Bissette founded the journal Revue des Colonies in 1834 in Paris[21]—perhaps the first journal published in Europe by a person of African descent.[22] He reported on anti-slavery and civil rights activism in the French Antilles and militant activities in Martinique.[23] In the first issue, Bissette praised the Charte des Îles, an 1833 law through which "free men of all colors" were granted full political and civil rights, while noting that "the colonies have as yet encountered the grand principles of philanthropy only as a theory; as for the actual practice of freedom, forget it."[24] In addition to abolitionist arguments, Bissette published news on the horrors of slavery, profiles of high-achieving men of African descent, and eulogies of the Haitian Revolution.[25] He helped further the literary careers of black intellectuals such as the Haitian writers Ignace Nau and Beauvais Lespinasse; the Martiniquais poet and politician Pierre Maria Pory-Papy; and the New Orleanian playwright Victor Séjour.[26] Joseph Saint-Rémy, born in Guadeloupe, wrote biographical sketches of Haitian writers for the journal. After the Revue folded in 1842, Bissette continued to write and make public statements on behalf of his cause.[27]

References

- ↑ Shirley Elizabeth Thompson, Exiles at Home: The Struggle to Become American in Creole New Orleans (Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 153; Carolyn Vellenga Berman, Creole Crossings: Domestic Fiction and the Reform of Colonial Slavery (Cornell University Press, 2006), p. 111.

- ↑ Robin Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848 (Verso, 1988), p. 492.

- ↑ Thompson, Exiles at Home, p. 153.

- ↑ Sugar and Slavery, Family and Race: The Letters and Diary of Pierre Dessalles, Planter in Martinique, 1808-1856 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 52.

- ↑ Sara E. Johnson, The Fear of French Negroes: Transcolonial Collaboration in the Revolutionary Americas (University of California Press, 2012), p. 237, note 8.

- ↑ Johnson, The Fear of French Negroes, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Berman, Creole Crossings, p. 111; Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 477.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 477.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 477; Berman, Creole Crossings, p. 111. The pamphlet was De la situation des gens de couleur libres aux Antilles françaises ("On the situation of free people of color in the French Antilles").

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 478.

- ↑ Thompson, Exiles at Home, p. 153.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 478.

- ↑ Berman, Creole Crossings, p. 111.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 484.

- ↑ Caryn Cossé Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana 1718–1868 (Louisiana State University Press, 1997), p. 96.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 492.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 514, note 26.

- ↑ Marika Sherwood, "Africans in Europe," in Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities, edited by Carl Skutsch (Routledge, 2005), p. 33.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 499.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 499.

- ↑ Thompson, Exiles at Home, p. 153.

- ↑ Sherwood, "Africans in Europe," p. 33.

- ↑ Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, p. 485.

- ↑ Berman, Creole Crossings, p. 112.

- ↑ Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, p. 95.

- ↑ Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, p. 96.

- ↑ Bell, Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition, p. 96.

Further reading

- Lawrence C. Jennings, "Cyril Bissette, Radical Black French Activist," French History 9 (1995).