Damascus Protocol

The Damascus Protocol was a document given to Faisal bin Hussein on 23 May 1915 by the Arab secret societies al-Fatat and Al-'Ahd[1] on his second visit to Damascus during a mission to consult Turkish officials in Constantinople.

The secret societies declared they would support Faisal's father Hussein bin Ali's revolt against the Ottoman Empire, if the demands in the protocol were submitted to the British. These demands, defining the territory of an independent Arab state to be established in the Middle East that would encompass all of the lands of Ottoman Western Asia south of the 37th parallel north.[2]

Crucially, this became the basis of the Arab understanding of the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence.

The Text

The text was first translated into English by George Antonius in 1938, based on a copy of the protocol given to him by Faisal:[3]

"The recognition by Great Britain of the independence of the Arab countries lying within the following frontiers:

North: The Line Mersin-Adana to parallel 37N. and thence along the line Birejek-Urga-Mardin-Midiat-Jazirat (Ibn 'Unear)-Amadia to the Persian frontier;

The grant of economic preference to Great Britain."

East: The Persian frontier down to the Persian Gulf;

South: The Indian Ocean (with the exclusion of Aden, whose status was to be maintained).

West: The Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea back to Mersin.

The abolition of all exceptional privileges granted to foreigners under the capitulations.

The conclusion of a defensive alliance between Great Britain and the future independent Arab State.

Background

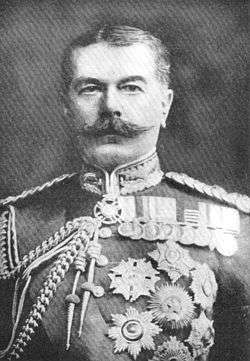

Negotiations with Kitchener

On 5 February 1914 the Sharif's son Abdullah met Herbert Kitchener, British Governor General of Egypt and the Sudan, in Cairo and asked him whether Hussein could rely on British support in the event of Turkish moves against the Hejaz. At this point Kitchener could offer no encouragement, but two months later Abdullah met with Kitchener's Oriental Secretary, Sir Ronald Storrs, and was given the assurance that Great Britain would guarantee the status quo in Arabia against "wanton Turkish aggression".[4]

British reluctance to oppose the Turks evaporated following the onset of war in August 1914. Kitchener, now Secretary of State for War, sent a message to Abdullah asking whether the Arabs would support Great Britain if Turkey joined the war on the side of Germany. Abdullah responded that the Sharif would support Britain in return for British support against the Turks.[4]

By the time of Kitchener's reply in October the Turks had joined the Germans,

Kitchener now stated that if the Amir and the 'Arab Nation' supported Britain in the war, the British would recognise and support the independence of the Amirate and of the Arabs and, further, would guarantee Arabia against external aggression. And then Kitchener gratuitously and on his own authority added a phrase that would generate controversy in London and the Middle East for years to come. 'It may be,' he concluded, 'that an Arab of the true race will assume the Caliphate at Mecca or Medina and so good may come by the help of God out of all the evil that is now occurring'.[5]

In his reply Hussein did not mention the Caliphate but said that he could not immediately break with the Turks because of his position in Islam.

The Turks declare Jihad

On 11 November 1914 the Turks declared a jihad against the Entente (Allies of World War I) and urged the Arab leader Husayn bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, to support the call and to contribute troops to their forces.[5]

Shortly after this declaration Hussein was approached by a representative of the Arab secret societies al-Fatat and Al-'Ahd who came to Mecca in January 1915 with the aim of persuading the Sharif to become leader of a revolt against the Ottomans. At the same time Hussein's eldest son Ali bin Hussein uncovered a Turkish plot to depose the Sharif in favour of Ali Haidar,[5] head of the dispossessed Motallib branch of the Sharifian family.[6] Hussein ordered his son Faisal to confront the Grand Vizier in Constantinople with evidence of the plot, but also to stop in Damascus to explore the viability of a revolt with the leaders of the secret socieities, which he did on 26 March 1915. After a month of talks Faisal was unconvinced of the strength of the Arab movement and concluded that a revolt would not succeed without the assistance of one of the Great Powers. On reaching Constantinople in April and receiving the news that an Arab declaration of jihad was viewed as essential by the Turks Faisal became equally concerned about his family's position in the Hejaz.[5]

On his return journey Faisal visited Damascus to resume talks with al-Fatat and Al-'Ahd and joined their revolutionary movement. It was during this visit that Faisal was presented with the document that became known as the 'Damascus Protocol'. The document declared that the Arabs would revolt in alliance with Great Britain in return for recognition of Arab independence in an area running from the 37th parallel north on the southern border of Turkey, bounded in the east by Persia and the Persian Gulf, in the west by the Mediterranean Sea and in the south by the Arabian Sea.[7]

Meeting at Ta'if

Following deliberations at Ta'if between Hussein and his sons in June 1915, during which Faisal counselled caution, Ali argued against rebellion and Abdullah advocated action, the Sharif set a tentative date for armed revolt for June 1916 and commenced negotiations with the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon via the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Herzog, 1975, p. 213.

- ↑ Ismael, 1991, p. 65.

- ↑ Antonius, George (1938). The Arab Awakening: The Story of the Arab National Movement. H. Hamilton. p. 157.

- 1 2 Paris, 2003, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Paris, 2003, p. 23.

- ↑ British Imperial Connexions to the Arab National Movement, 1912-1914, accessed 8 April 2007.

- 1 2 Paris, 2003, p. 24.

References

- Fromkin, David (1990). A Peace To End All Peace. Avon Books, New York. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8

- Herzog, Jacob David (1975). A People That Dwells Alone: Speeches and Writings of Yaacov Herzog. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Ismael, Tareq Y. (1991). Politics and Government in the Middle East and North Africa. University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-1043-8

- Paris, Timothy J. (2003). Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule, 1920-1925: The Sherifian Solution. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5451-5