David Cox (artist)

| David Cox | |

|---|---|

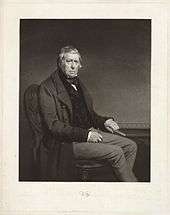

David Cox (1830) by William Radclyffe, oil on canvas. | |

| Born |

29 April 1783 Birmingham, England |

| Died |

7 June 1859 (aged 76) Birmingham, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | landscape, watercolour, oil painting |

| Notable work | Rhyl Sands (1854) |

David Cox (29 April 1783 – 7 June 1859) was an English landscape painter, one of the most important members of the Birmingham School of landscape artists[1] and an early precursor of impressionism.[2]

He is considered one of the greatest English landscape painters, and a major figure of the Golden age of English watercolour.[3]

Although most popularly known for his works in watercolour, he also painted over 300 works in oil towards the end of his career,[4] now considered "one of the greatest, but least recognised, achievements of any British painter."[5]

Early life in Birmingham, 1783–1804

Cox was born on 29 April 1783 on Heath Mill Lane in Deritend, then an industrial suburb of Birmingham.[6] His father was a blacksmith and whitesmith about whom little is known,[6] except that he supplied components such as bayonets and barrels to the Birmingham gun trade.[7] Cox's mother was the daughter of a farmer and miller from Small Heath to the east of Birmingham.[6] Early biographers record that "she had had a better education than his father, and was a woman of superior intelligence and force of character".[6] Cox was initially expected to follow his father into the metal trade and take over his forge, but his lack of physical strength led his family to seek opportunities for him to develop his interest in art,[8] which is said to have first become apparent when the young Cox started painting paper kites while recovering from a broken leg.[6]

By the late 18th century Birmingham had developed a network of private academies teaching drawing and painting, established to support the needs of the town's manufacturers of luxury metal goods,[9] but also encouraging education in fine art,[10] and nurturing the distinctive tradition of landscape art of the Birmingham School.[1] Cox initially enrolled in the academy of Joseph Barber in Great Charles Street, where fellow students included the artist Charles Barber and the engraver William Radclyffe, both of whom would become important lifelong friends.[9]

At the age of about 15 Cox was apprenticed to the Birmingham painter Albert Fielder, who produced portrait miniatures and paintings for the tops of snuffboxes from his workshop at 10 Parade in the northwest of the town.[11] Early biographers of Cox record that he left his apprenticeship after Feidler's suicide, with one reporting that Cox himself discovered his master's hanging body, but this is probably a myth as Fielder is recorded at his address in Parade as late as 1825.[12] At some time during mid-1800 Cox was given work by William Macready the elder at the Birmingham Theatre, initially as an assistant grinding colours and preparing canvases for the scene painters, but from 1801 painting scenery himself and by 1802 leading his own team of assistants and being credited in plays' publicity.[12]

London, 1804–1814

In 1804 Cox was promised work by the theatre impresario Philip Astley and moved to London, taking lodgings in 16 Bridge Row, Lambeth.[13] Although he was unable to get employment at Astley's Amphitheatre it is likely that he had already decided to try to establish himself as a professional artist, and apart from a few private commissions for painting scenery his focus over the next few years was to be on painting and exhibiting watercolours.[14] While living in London, Cox married his landlord's daughter, Mary Agg and the couple moved to Dulwich in 1808.

In 1805 he made his first of many trips to Wales, with Charles Barber, his earliest dated watercolours are from this year. Throughout his lifetime he made numerous sketching tours to the Home Counties, North Wales, Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Devon.

Cox exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy from 1805. His paintings never reached high prices, so he earned his living mainly as a drawing master. His first pupil, Colonel the Hon.H. Windsor (the future Earl of Plymouth) engaged him in 1808, Cox went on to acquire several other aristocratic and titled pupils. He also went on to write several books, including: Ackermanns' New Drawing Book (1809); A Series Of Progressive Lessons (1811); Treatise on Landscape Painting (1813); and Progressive Lessons on Landscape (1816). The ninth and last edition of his series Progressive Lessons, was published in 1845.

By 1810 he was elected President of the Associated Artists in Water Colour. In 1812, following the demise of the Associated Artists, he was elected as associate of the Society of Painters in Water Colour (the old Water Colour Society). He was elected a Member of the Society in 1813, and exhibited there every year (except 1815 and 1817) until his death.

Hereford, 1814–1827

In the summer of 1813 Cox was appointed as the drawing master of the Royal Military College in Farnham, Surrey, but he resigned shortly afterwards, finding little sympathy with the atmosphere of a military institution.[15] Soon after that he applied to a newspaper advertisement for a position as drawing master for Miss Crouchers' School for Young Ladies in Hereford and in Autumn 1814 moved to the town with his family.[15] Cox taught at the school in Widemarsh Street until 1819, his substantial salary of £100 per year requiring only two day's work per week, allowing time for painting and the taking of private pupils.[6]

Cox's reputation as both a painter and a teacher had been building over previous years, as indicated by his election as a member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours and his inclusion in John Hassell's 1813 book Aqua Pictura, which claimed to present works by "all of the most approved water coloured draftsmen".[15] The depression that accompanied the end of the Napoleonic Wars had caused a contraction in the art market, however, and by 1814 Cox had been very short of money, requiring a loan from one of his pupils to pay even for the move to Hereford.[15] Despite its financial advantages and its proximity to the scenery of North Wales and the Wye Valley, the move to Hereford marked a retreat in terms of his career as a painter: he sent few works to the annual exhibition of the Society of Painters in Water Colours during his first years away from London and not until 1823 would he again contribute more than 20 pictures.[16]

Between 1823 and 1826 he had Joseph Murray Ince as a pupil.[17]

London, 1827–1841

He made his first trip to the Continent, to Belgium and the Netherlands in 1826 and subsequently moved to London the following year.

He exhibited for the first time with the Birmingham Society of Artists in 1829, and with the Liverpool Academy in 1831. In 1839, two of Cox's watercolours were bought from the Old Water Colour Society exhibition by the Marquis of Conynha for Queen Victoria.

Birmingham, 1841–1859

In May 1840 Cox wrote to one of his Birmingham friends: "I am making preparations to sketch in oil, and also to paint, and it is my intention to spend most of my time in Birmingham for the purpose of practice".[18] Cox had been considering a return to painting in oils since 1836 and in 1839 had taken lessons in oil painting from William James Müller, to whom he had been introduced by mutual friend George Arthur Fripp.[19] Hostility between the Society of Painters in Water Colours and the Royal Academy made it difficult for an artist to be recognised for work in both watercolour and oil in London, however,[4] and it is likely that Cox would have preferred to explore this new medium in the more supportive environment of his home town.[18] By the early 1840s his income from sales of his watercolours was sufficient to allow him to abandon his work as a drawing master, and in June 1841 he moved with his wife to Greenfield House in Harborne, then a village on Birmingham's south western outskirts.[20] It was this move that would enable the higher levels of freedom and experimentation that were to characterise his later work.[21]

In Harborne Cox established a steady routine – working in watercolour in the morning and oils in the afternoon.[22] He would visit London every spring to attend the major exhibitions, followed by one or more sketching excursions, continuing the pattern that he had established in the 1830s.[21] From 1844 these tours evolved into a yearly trip to Betws-y-Coed in North Wales to work outdoors in both oil and watercolour, gradually becoming the focus for an annual summer artists colony that continued until 1856 with Cox as its "presiding genius".[23]

Cox's experience of trying to exhibit his oils in London was short and unsuccessful: in 1842 he made his only submission to the Society of British Artists; one oil painting was exhibited at each of the British Institution and the Royal Academy in 1843; and two oil paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844 – the last that would be exhibited in London during his lifetime.[24]

Cox showed regularly at the Birmingham Society of Arts and its successor, the Birmingham Society of Artists, becoming a member in 1842.[25]

Cox suffered a stroke on 12 June 1853 that temporarily paralysed him, and permanently affected his eyesight, memory and coordination.[26]

By 1857 however, his eyesight had deteriorated. An exhibition of his work was arranged in 1858 by the Conversazione Society Hampstead, and in 1859 a retrospective exhibition was held at the German Gallery Bond Street, London. Cox died several months later. He was buried in the churchyard of St Peters, Harborne, Birmingham, under a chestnut tree, alongside his wife Mary.

Work

Early work

In the spring of 1811 Cox made a small number of notable works in oils during a visit to Hastings with his family.[19] It is not known why he didn't continue working in this medium at the time, but the five known surviving examples were described in 1969 as "surely some of the most brilliant examples of the genre in England".[27]

Mature work

Cox reached artistic maturity after his move to Hereford in 1814.[6] Although only two major watercolours can confidently be traced to the period between Cox's arrival in the town and the end of the decade, both of these – Butcher's Row, Hereford of 1815 and Lugg Meadows, near Hereford of 1817 – mark advances on his earlier work.[28]

Later work

Cox's later work produced after his move to Birmingham in 1841 was marked by simplification, abstraction and a stripping down of detail.[29] His art of the period combined the breadth and weight characteristic of the earlier English watercolour school, together with a boldness and freedom of expression comparable to later impressionism.[30] His concern with capturing the fleeting nature of weather, atmosphere and light was similar to that of John Constable, but Cox stood apart from the older painter's focus on capturing material detail, instead employing a high degree of generalisation and a focus on overall effect.[31]

The quest for character over precision in representing nature was an established characteristic of the Birmingham School of landscape artists with which Cox had been associated early in his life,[32] and as early as 1810 Cox's work had been criticised for its "sketchiness of finish" and "cloudy confusion of objects", which were held to betray "the coarseness of scene-painting".[33] During the 1840s and 1850s Cox took this "peculiar manner" to new extremes, incorporating the techniques of the sketch into his finished works to a far greater degree.[34]

Cox's watercolour technique of the 1840s was sufficiently different from his earlier methods to need explanation to his son in 1842, despite the fact that his son had been helping him teach and paint since 1827.[35] The materials used for his later works in watercolour also differed from his earlier periods: he used black chalk instead of graphite pencil as his primary drawing medium, and the rough and absorbent "Scotch" wrapping paper for which he became well-known – both of these were related to his development of a rougher and freer style.[36]

Influence and legacy

By the 1840s Cox, alongside Peter De Wint and Copley Fielding, had become recognised as one of the leading figures of the English landscape watercolour style of the first half of the 19th century.[37] This judgement was complicated by reaction to the rougher and bolder style of Cox's later Birmingham work, which was widely ignored or condemned.[38] While by this time De Wint and Fielding were essentially continuing in a long-established tradition, Cox was creating a new one.[39]

A group of young artists working in Cox's watercolour style emerged well before his death, including William Bennett, David Hall McKewan and Cox's son David Cox Jr..[40] By 1850 Bennett in particular had become recognised as "perhaps the most distinguished among the landscape painters" for his Cox-like vigorous and decisive style.[41] Such early followers concentrated on the example of Cox's more moderate earlier work and steered clear of what were then seen as the excesses of Cox's later years.[41] During a period dominated by sleek and detailed picturesque landscape, however, they were still condemned by publications such as The Spectator as "the 'blottesque' school", and failed to establish themselves as a cohesive movement.[41]

John Ruskin in 1857 condemned the work of the Society of Painters in Water-colours as "a kind of potted art, of an agreeable flavour, suppliable and taxable as a patented commodity", excluding only the late work of Cox, about which he wrote "there is not any other landscape which comes near these works of David Cox in simplicity or seriousness".[42]

An 1881 book, A Biography of David Cox: With Remarks on His Works and Genius, was based on a manuscript by Cox's friend William Hall, edited and expanded by John Thackray Bunce, editor of the Birmingham Daily Post.[43]

There are two Blue Plaque memorials commemorating him at 116 Greenfield Road, Harborne, Birmingham, , and at 34 Foxley Road, Kennington, London, SW9, where he lived from 1827. . It can also be seen at the David Cox exhibition in Birmingham.

His pupils included Birmingham architectural artist, Allen Edward Everitt (1824–1882).

A bust of Cox is in the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists' gallery.

Public collections

Several of his works are in Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, having been donated by Joseph Henry Nettlefold, on the condition it opened on Sundays.[44] His work can also be seen at the British Museum, the Tate Gallery, and in Manchester, Newcastle, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Oxford and Cambridge. The Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight shows a number of Cox's watercolours bought by Lever through James Orrock. Some of them have since been confirmed as forgeries. An exhibition of his work was held at the Yale Center for British Art in the USA in 2008, travelling to Birmingham in 2009.[45]

Gallery

|

References

- 1 2 Grant, Maurice Harold (1958), "The Birmingham School of Landscape", A chronological history of the old English landscape painters, in oil, from the 16th century to the 19th century, 2, Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, p. 167, OCLC 499875203

- ↑ Pillement, Georges (1978), "The Precursors of Impressionism", in Sérullaz, Maurice, Phaidon Encyclopedia of Impressionism, Oxford: Phaidon, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-7148-1897-9

- ↑ Barker, Elizabeth E. (2004), Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrieved 2014-06-01

- 1 2 Wildman 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Wilcox, Scott (October 1983), "David Cox. Birmingham", The Burlington Magazine, 125 (967): 638, JSTOR 881452

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wildman 2013.

- ↑ Osborne 2008, p. 69.

- ↑ Osborne 2008, pp. 69-70.

- 1 2 Osborne 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ Hoock, Holger (2003), The King's Artists: The Royal Academy of Arts and the Politics of British Culture 1760-1840, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 91–92, ISBN 0191556106, retrieved 2014-05-26

- ↑ Osborne 2008, pp. 71-72.

- 1 2 Osborne 2008, p. 73.

- ↑ Wildman 2003.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilcox 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ James Murray Ince, Dictionary of National Biography

- 1 2 Wildman 2008, p. 115.

- 1 2 Wildman 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 13.

- 1 2 Wilcox 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Wildman 2008, pp. 116-117.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Wildman 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Flynn, Brendan (2014). A Place for Art: The Story of the RBSA. Royal Birmingham Society of Artists. ISBN 978-0-9930294-0-0.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Gage, John (1969), A decade of English naturalism, 1810-1820, Norwich: University of East Anglia, p. 12, OCLC 6705579, retrieved 2014-06-01

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 53.

- ↑ Wildman, Stephen (1990), The Birmingham school: paintings, drawings and prints by Birmingham artists from the permanent collection, Birmingham: Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-7093-0171-4

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, p. 38.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Wilcox 2008, pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Wilcox & Newall 1992, pp. 17, 20.

- ↑ Wilcox & Newall 1992.

- ↑ Wilcox & Newall 1992, pp. 20-21.

- ↑ Wilcox & Newall 1992, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox & Newall 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Wilcox & Newall 1992, p. 18.

- ↑ Hall, William (1881). A Biography of David Cox: With Remarks on His Works and Genius. Editied with additions, by John Thackray Bunce.

- ↑ Barbara M. D. Smith, ‘Nettlefold, Joseph Henry (1827–1881)’, rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ↑

Bibliography

- Osborne, Victoria (2008), "Cox and Birmingham", in Wilcox, Scott, Sun, Wind, and Rain: the art of David Cox, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 69–83, ISBN 0300117442

- Wilcox, Scott; Newall, Christopher (1992), Victorian Landscape Watercolors, New York: Hudson Hills, ISBN 155595071X, retrieved 2014-06-01

- Wilcox, Scott (2008), "The Work of the Mind", in Wilcox, Scott, Sun, Wind, and Rain: the art of David Cox, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 1–67, ISBN 0300117442

- Wildman, Stephen (2008), "David Cox's Development and Reputation as an Oil Painter", in Wilcox, Scott, Sun, Wind, and Rain: the art of David Cox, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 113–127, ISBN 0300117442

- Wildman, Stephen (2013), "Cox, David (1783–1859), landscape painter", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 2014-05-24

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to David Cox. |

- Paintings by David Cox at the Art UK site