Dementia praecox

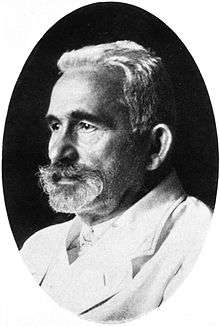

Dementia praecox (a "premature dementia" or "precocious madness") is a chronic, deteriorating psychotic disorder characterized by rapid cognitive disintegration, usually beginning in the late teens or early adulthood. Schizophrenia is the new word describing this disease. The term was first used in 1891 by Arnold Pick (1851–1924), a professor of psychiatry at Charles University in Prague.[1] His brief clinical report described the case of a person with a psychotic disorder resembling hebephrenia. German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) popularised it in his first detailed textbook descriptions of a condition that eventually became a different disease concept and relabeled as schizophrenia.[2] Kraepelin reduced the complex psychiatric taxonomies of the nineteenth century by dividing them into two classes: manic-depressive psychosis and dementia praecox. This division, commonly referred to as the Kraepelinian dichotomy, had a fundamental impact on twentieth-century psychiatry, though it has also been questioned.[3]

The primary disturbance in dementia praecox is a disruption in cognitive or mental functioning in attention, memory, and goal-directed behaviour. Kraepelin contrasted this with manic-depressive psychosis, now termed bipolar disorder, and also with other forms of mood disorder, including major depressive disorder. He eventually concluded that it was not possible to distinguish his categories on the basis of cross-sectional symptoms.[4]

Kraepelin viewed dementia praecox as a progressively deteriorating disease from which no one recovered. However, by 1913, and more explicitly by 1920, Kraepelin admitted that while there may be a residual cognitive defect in most cases, the prognosis was not as uniformly dire as he had stated in the 1890s. Still, he regarded it as a specific disease concept that implied incurable, inexplicable madness.

History

[T]he history of dementia praecox is really that of psychiatry as a whole— Adolf Meyer[5]

First use of the term

.gif)

Dementia is an ancient term which has been in use since at least the time of Lucretius in 50 B.C.E. where it meant "being out of one's mind".[6] Until the seventeenth century dementia referred to states of cognitive and behavioural deterioration leading to psychosocial incompetence. This condition could be innate or acquired and the concept had no reference to a necessarily irreversible condition. It is the concept in this popular notion of psychosocial incapacity that forms the basis for the idea of legal incapacity.[7] By the eighteenth century, at the period when the term entered into European medical discourse, clinical concepts were added to the vernacular understanding such that dementia was now associated with intellectual deficits arising from any cause and at any age.[8] By the end of the nineteenth century the modern 'cognitive paradigm' of dementia was taking root.[9] This holds that dementia is understood in terms of criteria relating to aetiology, age and course which excludes former members of the family of the demented such as adults with acquired head trauma or children with cognitive deficits. Moreover, it was now understood as an irreversible condition and a particular emphasis was placed on memory loss in regard to the deterioration of intellectual functions.[10]

The term démence précoce was used in passing to describe the characteristics of a subset of young mental patients by the French physician Bénédict Augustin Morel in 1852 in the first volume of his Études cliniques.[11] and the term is used more frequently in his textbook Traité des maladies mentales which was published in 1860.[12] Morel, whose name will be forever associated with religiously inspired concept of degeneration theory in psychiatry, used the term in a descriptive sense and not to define a specific and novel diagnostic category. It was applied as a means of setting apart a group of young men and women who were suffering from "stupor."[13] As such their condition was characterised by a certain torpor, enervation, and disorder of the will and was related to the diagnostic category of melancholia. He did not conceptualise their state as irreversible and thus his use of the term dementia was equivalent to that formed in the eighteenth century as outlined above.[14]

While some have sought to interpret, if in a qualified fashion, the use by Morel of the term démence précoce as amounting to the "discovery" of schizophrenia,[13] others have argued convincingly that Morel's descriptive use of the term should not be considered in any sense as a precursor to Kraepelin's dementia praecox disease concept.[10] This is due to the fact that their concepts of dementia differed significantly from each other, with Kraepelin employing the more modern sense of the word and that Morel was not describing a diagnostic category. Indeed, until the advent of Pick and Kraepelin, Morel's term had vanished without a trace and there is little evidence to suggest that either Pick or indeed Kraepelin were even aware of Morel's use of the term until long after they had published their own disease concepts bearing the same name.[15] As Eugène Minkowski succinctly stated, 'An abyss separates Morel's démence précoce from that of Kraepelin.'[16]

Morel described several psychotic disorders that ended in dementia, and as a result he may be regarded as the first alienist or psychiatrist to develop a diagnostic system based on presumed outcome rather than on the current presentation of signs and symptoms. Morel, however, did not conduct any long-term or quantitative research on the course and outcome of dementia praecox (Kraepelin would be the first in history to do that) so this prognosis was based on speculation. It is impossible to discern whether the condition briefly described by Morel was equivalent to the disorder later called dementia praecox by Pick and Kraepelin.

Time component

Psychiatric nosology in the nineteenth-century was chaotic and characterised by a conflicting mosaic of contradictory systems.[17] Psychiatric disease categories were based upon short-term and cross-sectional observations of patients from which were derived the putative characteristic signs and symptoms of a given disease concept.[18] The dominant psychiatric paradigms which gave a semblance of order to this fragmentary picture were Morelian degeneration theory and the concept of "unitary psychosis" (Einheitspsychose).[19] This latter notion, derived from the Belgian psychiatrist Joseph Guislain (1797–1860), held that the variety of symptoms attributed to mental illness were manifestations of a single underlying disease process.[20] While these approaches had a diachronic aspect they lacked a conception of mental illness that encompassed a coherent notion of change over time in terms of the natural course of the illness and based upon an empirical observation of changing symptomatology.[21]

In 1863, the Danzig-based psychiatrist Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum (1828–1899) published his text on psychiatric nosology Die Gruppierung der psychischen Krankheiten (The Classification of Psychiatric Diseases).[22] Although with the passage of time this work would prove profoundly influential, when it was published it was almost completely ignored by German academia despite the sophisticated and intelligent disease classification system which it proposed.[23] In this book Kahlbaum categorized certain typical forms of psychosis (vesania typica) as a single coherent type based upon their shared progressive nature which betrayed, he argued, an ongoing degenerative disease process.[24] For Kahlbaum the disease process of vesania typica was distinguished by the passage of the sufferer through clearly defined disease phases: a melancholic stage; a manic stage; a confusional stage; and finally a demented stage.[25]

In 1866 Kahlbaum became the director of a private psychiatric clinic in Görlitz (Prussia, today Saxony, a small town near Dresden). He was accompanied by his younger assistant, Ewald Hecker (1843–1909), and during a ten-year collaboration they conducted a series of research studies on young psychotic patients that would become a major influence on the development of modern psychiatry.

Together Kahlbaum and Hecker were the first to describe and name such syndromes as dysthymia, cyclothymia, paranoia, catatonia, and hebephrenia.[26] Perhaps their most lasting contribution to psychiatry was the introduction of the "clinical method" from medicine to the study of mental diseases, a method which is now known as psychopathology.

When the element of time was added to the concept of diagnosis, a diagnosis became more than just a description of a collection of symptoms: diagnosis now also defined by prognosis (course and outcome). An additional feature of the clinical method was that the characteristic symptoms that define syndromes should be described without any prior assumption of brain pathology (although such links would be made later as scientific knowledge progressed). Karl Kahlbaum made an appeal for the adoption of the clinical method in psychiatry in his 1874 book on catatonia. Without Kahlbaum and Hecker there would be no dementia praecox.[27]

Upon his appointment to a full professorship in psychiatry at the University of Dorpat (now Tartu, Estonia) in 1886, Kraepelin gave an inaugural address to the faculty outlining his research programme for the years ahead. Attacking the "brain mythology" of Meynert and the positions of Griesinger and Gudden, Kraepelin advocated that the ideas of Kahlbaum, who was then a marginal and little known figure in psychiatry, should be followed. Therefore, he argued, a research programme into the nature of psychiatric illness should look at a large number of patients over time to discover the course which mental disease could take.[28] It has also been suggested that Kraepelin's decision to accept the Dorpat post was informed by the fact that there he could hope to gain experience with chronic patients and this, it was presumed, would facilitate the longitudinal study of mental illness.[29]

Quantitative component

Understanding that objective diagnostic methods must be based on scientific practice, Kraepelin had been conducting psychological and drug experiments on patients and normal subjects for some time when, in 1891, he left Dorpat and took up a position as professor and director of the psychiatric clinic at Heidelberg University. There he established a research program based on Kahlbaum's proposal for a more exact qualitative clinical approach, and his own innovation: a quantitative approach involving meticulous collection of data over time on each new patient admitted to the clinic (rather than only the interesting cases, as had been the habit until then).

Kraepelin believed that by thoroughly describing all of the clinic's new patients on index cards, which he had been using since 1887, researcher bias could be eliminated from the investigation process.[30] He described the method in his posthumously published memoir:

... after the first thorough examination of a new patient, each of us had to throw in a note [in a "diagnosis box"] with his diagnosis written on it. After a while, the notes were taken out of the box, the diagnoses were listed, and the case was closed, the final interpretation of the disease was added to the original diagnosis. In this way, we were able to see what kind of mistakes had been made and were able to follow-up the reasons for the wrong original diagnosis.[31]

The fourth edition of his textbook, Psychiatrie, published in 1893, two years after his arrival at Heidelberg, contained some impressions of the patterns Kraepelin had begun to find in his index cards. Prognosis (course and outcome) began to feature alongside signs and symptoms in the description of syndromes, and he added a class of psychotic disorders designated "psychic degenerative processes", three of which were borrowed from Kahlbaum and Hecker: dementia paranoides (a degenerative type of Kahlbaum's paranoia, with sudden onset), catatonia (per Kahlbaum, 1874) and dementia praecox, (Hecker's hebephrenia of 1871). Kraepelin continued to equate dementia praecox with hebephrenia for the next six years.[30]

In the March 1896 fifth edition of Psychiatrie, Kraepelin expressed confidence that his clinical method, involving analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data derived from long term observation of patients, would produce reliable diagnoses including prognosis:

What convinced me of the superiority of the clinical method of diagnosis (followed here) over the traditional one, was the certainty with which we could predict (in conjunction with our new concept of disease) the future course of events. Thanks to it the student can now find his way more easily in the difficult subject of psychiatry.[32]

In this edition dementia praecox is still essentially hebephrenia, and it, dementia paranoides and catatonia are described as distinct psychotic disorders among the "metabolic disorders leading to dementia".[33]

Kraepelin's influence on the next century

In the 1899 (6th) edition of Psychiatrie, Kraepelin established a paradigm for psychiatry that would dominate the following century, sorting most of the recognized forms of insanity into two major categories: dementia praecox and manic-depressive illness. Dementia praecox was characterized by disordered intellectual functioning, whereas manic-depressive illness was principally a disorder of affect or mood; and the former featured constant deterioration, virtually no recoveries and a poor outcome, while the latter featured periods of exacerbation followed by periods of remission, and many complete recoveries. The class, dementia praecox, comprised the paranoid, catatonic and hebephrenic psychotic disorders, and these forms were found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until the fifth edition was released, in May 2013. These terms, however, are still found in general psychiatric nomenclature. The ICD-10 still uses "hebephrenic" to designate the third type.[34]

Change in prognosis

In the seventh, 1904, edition of Psychiatrie, Kraepelin accepted the possibility that a small number of patients may recover from dementia praecox. Eugen Bleuler reported in 1908 that in many cases there was no inevitable progressive decline, there was temporary remission in some cases, and there were even cases of near recovery with the retention of some residual defect. In the eighth edition of Kraepelin's textbook, published in four volumes between 1909 and 1915, he described eleven forms of dementia, and dementia praecox was classed as one of the "endogenous dementias". Modifying his previous more gloomy prognosis in line with Bleuler's observations, Kraepelin reported that about 26% of his patients experienced partial remission of symptoms. Kraepelin died while working on the ninth edition of Psychiatrie with Johannes Lange (1891–1938), who finished it and brought it to publication in 1927.[35]

Etiology

Though his work and that of his research associates had revealed a role for heredity, Kraepelin realized nothing could be said with certainty about the aetiology of dementia praecox, and he left out speculation regarding brain disease or neuropathology in his diagnostic descriptions. Nevertheless, from the 1896 edition onwards Kraepelin made clear his belief that poisoning of the brain, "auto-intoxication," probably by sex hormones, may underlie dementia praecox – a theory also entertained by Eugen Bleuler. Both theorists insisted dementia praecox is a biological disorder, not the product of psychological trauma. Thus, rather than a disease of hereditary degeneration or of structural brain pathology, Kraepelin believed dementia praecox was due to a systemic or "whole body" disease process, probably metabolic, which gradually affected many of the tissues and organs of the body before affecting the brain in a final, decisive cascade.[36] Kraepelin, recognizing dementia praecox in Chinese, Japanese, Tamil and Malay patients, suggested in the eighth edition of Psychiatrie that, "we must therefore seek the real cause of dementia praecox in conditions which are spread all over the world, which thus do not lie in race or in climate, in food or in any other general circumstance of life..."[37]

Treatment

Kraepelin had experimented with hypnosis but found it wanting, and disapproved of Freud's and Jung's introduction, based on no evidence, of psychogenic assumptions to the interpretation and treatment of mental illness. He argued that, without knowing the underlying cause of dementia praecox or manic-depressive illness, there could be no disease-specific treatment, and recommended the use of long baths and the occasional use of drugs such as opiates and barbiturates for the amelioration of distress, as well as occupational activities, where suitable, for all institutionalized patients. Based on his theory that dementia praecox is the product of autointoxication emanating from the sex glands, Kraepelin experimented, without success, with injections of thyroid, gonad and other glandular extracts.[37]

Use of term spreads

Kraepelin noted the dissemination of his new disease concept when in 1899 he enumerated the term's appearance in almost twenty articles in the German-language medical press.[37] In the early years of the twentieth century the twin pillars of the Kraepelinian dichotomy, dementia praecox and manic depressive psychosis, were assiduously adopted in clinical and research contexts among the Germanic psychiatric community.[37] German-language psychiatric concepts were always introduced much faster in America (than, say, Britain) where émigré German, Swiss and Austrian physicians essentially created American psychiatry. Swiss-émigré Adolf Meyer (1866–1950), arguably the most influential psychiatrist in America for the first half of the 20th century, published the first critique of dementia praecox in an 1896 book review of the 5th edition of Kraepelin's textbook. But it was not until 1900 and 1901 that the first three American publications regarding dementia praecox appeared, one of which was a translation of a few sections of Kraepelin's 6th edition of 1899 on dementia praecox.

Adolf Meyer was the first to apply the new diagnostic term in America. He used it at the Worcester Lunatic Hospital in Massachusetts in the fall of 1896. He was also the first to apply Eugen Bleuler's term "schizophrenia" (in the form of "schizophrenic reaction") in 1913 at the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The dissemination of Kraepelin's disease concept to the Anglophone world was facilitated in 1902 when Ross Diefendorf, a lecturer in psychiatry at Yale, published an adapted version of the sixth edition of the Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. This was republished in 1904 and with a new version, based on the seventh edition of Kraepelin's Lehrbuch appearing in 1907 and reissued in 1912.[38][39] Both dementia praecox (in its three classic forms) and "manic-depressive psychosis" gained wider popularity in the larger institutions in the eastern United States after being included in the official nomenclature of diseases and conditions for record-keeping at Bellevue Hospital in New York City in 1903. The term lived on due to its promotion in the publications of the National Committee on Mental Hygiene (founded in 1909) and the Eugenics Records Office (1910). But perhaps the most important reason for the longevity of Kraepelin's term was its inclusion in 1918 as an official diagnostic category in the uniform system adopted for comparative statistical record-keeping in all American mental institutions, The Statistical Manual for the Use of Institutions for the Insane. Its many revisions served as the official diagnostic classification scheme in America until 1952 when the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Mental Disorders, or DSM-I, appeared. Dementia praecox disappeared from official psychiatry with the publication of DSM-I, replaced by the Bleuler/Meyer hybridization, "schizophrenic reaction".

Schizophrenia was mentioned as an alternate term for dementia praecox in the 1918 Statistical Manual. In both clinical work as well as research, between 1918 and 1952 five different terms were used interchangeably: dementia praecox, schizophrenia, dementia praecox (schizophrenia), schizophrenia (dementia praecox) and schizophrenic reaction. This made the psychiatric literature of the time confusing since, in a strict sense, Kraepelin's disease was not Bleuler's disease. They were defined differently, had different population parameters, and different concepts of prognosis.

The reception of dementia praecox as an accepted diagnosis in British psychiatry came more slowly, perhaps only taking hold around the time of World War I. There was substantial opposition to the use of the term "dementia" as misleading, partly due to findings of remission and recovery. Some argued that existing diagnoses such as "delusional insanity" or "adolescent insanity" were better or more clearly defined.[40] In France a psychiatric tradition regarding the psychotic disorders predated Kraepelin, and the French never fully adopted Kraepelin's classification system. Instead the French maintained an independent classification system throughout the 20th century. From 1980, when DSM-III totally reshaped psychiatric diagnosis, French psychiatry began to finally alter its views of diagnosis to converge with the North American system. Kraepelin thus finally conquered France via America.

From dementia praecox to schizophrenia

Due to the influence of alienists such as Adolf Meyer, August Hoch, George Kirby, Charles Macphie Campbell, Smith Ely Jelliffe and William Alanson White, psychogenic theories of dementia praecox dominated the American scene by 1911. In 1925 Bleuler's schizophrenia rose in prominence as an alternative to Kraepelin's dementia praecox. When Freudian perspectives became influential in American psychiatry in the 1920s schizophrenia became an attractive alternative concept. Bleuler corresponded with Freud and was connected to Freud's psychoanalytic movement,[41] and the inclusion of Freudian interpretations of the symptoms of schizophrenia in his publications on the subject, as well as those of C.G. Jung, eased the adoption of his broader version of dementia praecox (schizophrenia) in America over Kraepelin's narrower and prognostically more negative one.

The term "schizophrenia" was first applied by American alienists and neurologists in private practice by 1909 and officially in institutional settings in 1913, but it took many years to catch on. It is first mentioned in The New York Times in 1925. Until 1952 the terms dementia praecox and schizophrenia were used interchangeably in American psychiatry, with occasional use of the hybrid terms "dementia praecox (schizophrenia)" or "schizophrenia (dementia praecox)".

Diagnostic manuals

Editions of the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders since the first in 1952 had reflected views of schizophrenia as "reactions" or "psychogenic" (DSM-I), or as manifesting Freudian notions of "defense mechanisms" (as in DSM-II of 1969 in which the symptoms of schizophrenia were interpreted as "psychologically self-protected"). The diagnostic criteria were vague, minimal and wide, including either concepts that no longer exist or that are now labeled as personality disorders (for example, schizotypal personality disorder). There was also no mention of the dire prognosis Kraepelin had made. Schizophrenia seemed to be more prevalent and more psychogenic and more treatable than either Kraepelin or Bleuler would have allowed.

Conclusions

As a direct result of the effort to construct Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) in the 1970s that were independent of any clinical diagnostic manual, Kraepelin's idea that categories of mental disorder should reflect discrete and specific disease entities with a biological basis began to return to prominence. Vague dimensional approaches based on symptoms—so highly favored by the Meyerians and psychoanalysts—were overthrown. For research purposes, the definition of schizophrenia returned to the narrow range allowed by Kraepelin's dementia praecox concept. Furthermore, after 1980 the disorder was a progressively deteriorating one once again, with the notion that recovery, if it happened at all, was rare. This revision of schizophrenia became the basis of the diagnostic criteria in DSM-III (1980). Some of the psychiatrists who worked to bring about this revision referred to themselves as the "neo-Kraepelinians".

Footnotes

- ↑ Hoenig 1995, p. 337.

- ↑ Yuhas, Daisy. "Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Has Remained a Challenge (Timeline)". Scientific American Mind (March 2013). Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Greene 2007, p. 361.

- ↑ Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 134.

- ↑ Sass 1994, p. .

- ↑ Berrios 1996, p. 172; Malgorzata 2004, p. 2; Bourgeois 2005, p. 199; Adams 1997, p. 183

- ↑ Berrios 1996, p. 172; Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 116

- ↑ Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 116.

- ↑ Burns 2009, pp. 199–200.

- 1 2 Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 117.

- ↑ Hoenig 1995, p. 337; Boyle 2002, p. 46. Berrios, Luque and Villagran contend in their 2003 article on schizophrenia that Morel's first use dates to the publication in 1860 of Traité des maladies mentales (Berrios & Luque Villagran2003, p. 117; Morel 1860). Dowbiggin inaccurately states that Morel used the term on page 234 of the first volume of his 1852 publication Etudes cliniques (Dowbiggin 1996, p. 388; Morel 1852, p. 234). On page 235] Morel does refer to démence juvénile in positing that senility is not an age specific affliction and he also remarks that at his clinic he sees almost as many young people suffering from senility as old people (Morel 1852, p. 235). Also, as Hoenig accurately states, Morel uses the term twice in his 1852 text on pages 282 and 361 (Hoenig 1995, p. 337; Morel 1852, pp. 282, 361). In the first instance the reference is made in relation to young girls of asthenic build who have often also suffered from typhoid. It is a description and not a diagnostic category (Morel 1852, p. 282). In the next instance the term is used to argue that the illness course for those who suffer mania does not normally terminate in an early form of dementia (Morel 1852, p. 361).

- ↑ Berrios & Luque Villagran2003, p. 117. The term Démence précoce is used by Morel once in his 1857 text Traité des dégénérescence physiques, intellectuelles, et morales de l'espèce humaine (Morel 1857, p. 391) and seven times in his 1860 book Traité des maladies mentales (Morel 1860, pp. 119, 279, 516, 526, 532, 536, 552).

- 1 2 Dowbiggin 1996, p. 388.

- ↑ Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 118.

- ↑ While Berrios, Luque and Villagran argue this point forcefully (Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 117), others baldly state that Kraepelin was clearly inspired by Morel's lead. Yet no evidence of this claim is offered. For example, Stone 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Quoted in Berrios, Luque & Villagran 2003, p. 117.

- ↑ Kraam 2008, p. 77; Jablensky 1999, p. 96; Scharfetter 2001, p. 34; Engstrom 2003, p. 27

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. 145; Hoenig 1995, pp. 337–8; Kraam 2009, p. 88

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. 145; Engstrom 2003, p. 27

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. 145

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. 242.

- ↑ Engstrom 2003, p. 263; Pillmann & Marneros 2003, p. 163; Kahlbaum 1863

- ↑ Kraam 2009, p. 87.

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. 242; Pillmann & Marneros 2003, p. 163

- ↑ Kraam 2009, p. 105; Kahlbaum 1863, p. 135

- ↑ Porter 1999, p. 512.

- ↑ Hoenig 1995, pp. 337–8.

- ↑ Steinberger & Angermeyer 2001, pp. 297–327.

- ↑ Berrios 1996, p. 23.

- 1 2 Noll 2007a, p. xiv.

- ↑ Kraepelin 1987, p. 61

- ↑ Kraepelin 1896, p. v quoted in Noll 2007a, p. xiv

- ↑ Noll 2007a, p. xiv

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association 2000, p. 303.

- ↑ Noll 2007a, pp. 126–7

- ↑ Noll, Richard. "Whole Body Madness". Psychiatric times. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Noll 2007a, p. 127.

- ↑ Dain 1980, pp. 34, 341 n. 38.

- ↑ Diefendorf 1912, pp. 219–75.

- ↑ Ion & Beer 2002a, pp. 285–304; Ion & Beer 2002b, pp. 419–31

- ↑ Makari, George. Revolution in Mind: The Creation of Psychoanalysis, Harper Perennial: New York, 2008.

Bibliography

- Adams, Trevor (1997). "Dementia". In Norman, Ian J.; Redfern, Sally J. Mental Health Care for Elderly People. London. pp. 183–204. ISBN 9780443051739.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- American Psychiatric Association (2011). "B00 Schizophrenia: Proposed Revision". DSM-5 Development. American Psychiatric Association.

- Berrios, German E.; Hauser, R. (1995). "Kraepelin. Clinical Section — Part II". In Berrios, German E.; Porter, Roy. A History of Clinical Psychiatry: The Origin and History of Psychiatric Disorders. London. pp. 280–92.

- Berrios, German E. (1996). The History of Mental Symptoms: Descriptive Psychopathology since the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge.

- Berrios, German E.; Luque, Rogelio; Villagran, Jose M. (2003). "Schizophrenia: a conceptual history" (PDF). International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 3: 111–140.

- Bourgeois, Michelle S. (2005). "Dementia". In La Pointe, Leonard L. Aphasia and Related Neurogenic Language Disorders. New York. pp. 199–212. ISBN 9781588902269.

- Boyle, Mary (2002). Schizophrenia: A Scientific Delusion? (2nd ed.). London. ISBN 9780415227186.

- Burns, Alastair (2009). "Another nail in the coffin for the cognitive paradigm of dementia". British Journal of Psychiatry. 194 (3): 199–200. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058537. PMID 19252143.

- Dain, Norman (1980). Clifford W. Beers, advocate for the insane. Pittsburgh PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-3419-1.

- Diefendorf, A. Ross (1912). Clinical Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians Abstracted and Adapted from the Seventh German Edition of Kraepelin's "Lehrbuch Der Psychiatrie". London.

- Dowbiggin, Ian (1996). "Back to the future: Valentin Magnan, French psychiatry, and the classification of mental diseases, 1885–1925'". Social History of Medicine. 9 (3): 383–408. doi:10.1093/shm/9.3.383. PMID 11618728.

- Engstrom, Eric J. (2003). Clinical Psychiatry in Imperial Germany: A History of Psychiatric Practice. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4195-1.

- Greene, Tayla (2007). "The Kraepelinian dichotomy: twin pillars crumbling?". History of Psychiatry. 18 (3): 361–79. doi:10.1177/0957154X07078977.

- Hippius, Hanns; Muller, Norbert (2008). "The work of Emil Kraepelin and his research group in Munchen". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 258 (Suppl. 2): 3–11. doi:10.1007/s00406-008-2001-6. PMID 18516510.

- Hoenig, J (1995). "Schizophrenia: clinical section". In Berrios, German E.; Porter,Roy. A History of Clinical Psychiatry: The Origin and History of Psychiatric Disorders. London. pp. 336–48. ISBN 0-485-24011-4.

- Ion, R.M.; Beer, M.D. (2002a). "The British reaction to dementia praecox 1893–1913. Part 1". History of Psychiatry. 13 (51 Pt 3): 285–304. doi:10.1177/0957154X0201305103. PMID 12503573.

- Ion, R.M.; Beer, M.D. (2002b). "The British reaction to dementia praecox 1893–1913. Part 2". History of Psychiatry. 13 (52 Pt 4): 419–31. doi:10.1177/0957154X0201305204. PMID 12645570.

- Kahlbaum, Karl Ludwig (1863). Die Gruppierung der psychischen Krankheiten und die Eintheilung der Seelenstörungen: Entwurf einer historisch-kritischen Darstellung der bisherigen Eintheilungen und Versuch zur Anbahnung einer empirisch-wissenschaftlichen Grundlage der Psychiatrie als klinischer Disciplin. Danzig: Kafemann.

- Kraam, Abdullah (2008). "Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum by Dr. Ewald Hecker (1899)". History of Psychiatry. 19 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1177/0957154X07084879.

- Kraam, Abdullah (2009). "'Hebephrenia. A contribution to clinical psychiatry.' By Dr. Ewald Hecker in Görlitz". History of Psychiatry. 20 (1): 87–106. doi:10.1177/0957154X08099416.

- Kraepelin, Emil (1896). Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. Funfte, vollstandig umgearbeitete Auflage. Leipzig.

- Kraepelin, Emil (1987). Memoirs. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Kraepelin, Emil (1990). Quen, Jacques, ed. Psychiatry: A Textbook for Students and Physicians. Trans. Metoui, Helga; Ayed, Sabine. Canton, MA: Science History Publications.

- Malgorzata, B. Franczak, M.D.; Rama Maganti, M.D. (2004). "Neurodegenerative disorders: dementia" (PDF). Hospital Physician Neurology Board Review Manual. 8 (4): 2.

- Morel, B.A. (1852). Études cliniques: traité, théorique et pratique des maladies mentales. Vol. 1. Nancy.

- Morel, B.A. (1857). Traité des dégénérescence physiques, intellectuelles, et morales de l'espèce humaine. Paris: J.B. Balliere. ISBN 9780405074462.

- Morel, B.A. (1860). Traité des maladies mentales. Paris.

- Noll, Richard (2011). American Madness: The Rise and Fall of Dementia Praecox. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04739-6.

- Noll, Richard (2007a). The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders (3rd ed.). New York. ISBN 9780816075089.

- Noll, Richard (2007b). "Kraepelin's 'lost biological psychiatry'? Autointoxication, organotherapy and surgery for dementia praecox". History of Psychiatry. 18 (3): 301–19. doi:10.1177/0957154X07078705.

- Noll, Richard (2007c). "History of Psychiatry". 18 (4): 483–502.

- Noll, Richard (2006a). "History of * Psychiatry". 17 (2): 183–204.

- Noll, Richard (2006b). "Infectious insanities, surgical solutions: Bayard Taylor Holmes, dementia praecox and laboratory science in early twentieth-century America. Part 2". 17 (3): 299–311.

- Noll, Richard (2006c). "The blood of the insane". History of Psychiatry. 17 (4): 395–418. doi:10.1177/0957154X06059440. PMID 17333671.

- Noll, Richard (2006d). "Chicago's Dr. Bayard Taylor Holmes: A forgotten pioneer in the history of biological psychiatry". Chicago Medicine. 109: 28–32.

- Noll, Richard (2004a). "Historical Review: Autointoxication and focal infection theories of dementia praecox". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 5 (2): 66–72. doi:10.1080/15622970410029914. PMID 15179665.

- Noll, Richard (2004b). "Dementia Praecox Studies". Schizophrenia Research. 68 (1): 103–4. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00219-6. PMID 15037344.

- Noll, Richard (2004c). "The American reaction to dementia praecox, 1900". History of Psychiatry. 15: 127–8. doi:10.1177/0957154X04041832.

- Noll, Richard (1999). "Styles of psychiatric practice: clinical evaluations of the same patient by James Jackson Putnam, Adolf Meyer, August Hoch, Emil Kraepelin and Smith Ely Jelliffe". History of Psychiatry. 10 (38 Pt 2): 145–89. doi:10.1177/0957154X9901003801. PMID 11623876.

- Pillmann, F.; Marneros, A. (2003). "Brief and acute psychoses: the development of concepts". History of Psychiatry. 14 (2): 161–77. doi:10.1177/0957154X030142002.

- Porter, Roy (1999). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. London. ISBN 0-00-637454-9.

- Sass, Louis Arnorsson (1994). The Paradox of Delusion: Wittgenstein, Schreber and the Schizophrenic Mind. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9899-6.

- Scharfetter, C. (2001). "Eugen Bleuler's schizophrenias – synthesis of various concepts" (PDF). Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 152 (1): 34–37.

- Shorter, Edward (1997). A History of Psychiatry: from the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac. New York. ISBN 9780471245315.

- Shorter, Edward (2005). "Schizophrenia/Dementia Praecox: Emergence of the Concept". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 267–79. ISBN 0-19-517668-5.

- Steinberger, Holger; Angermeyer, Matthias C. (2001). "Emil Kraepelin's years at Dorpat as professor of psychiatry in nineteenth-century Russia". History of Psychiatry. 12 (47): 297–327. doi:10.1177/0957154X0101204703. PMID 11951915.

- Stone, Michael H. (2006). "History of schizophrenia and its antecedents". In Lieberman, Jeffrey A.; Stroup, T. Scott; Perkins, Diana O. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Schizophrenia. Arlington. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9781585626465.

- Weber, Matthias M.; Engstrom, Eric J. (1997). "Kraepelin's 'diagnostic cards': the confluence of clinical research and preconceived categories". History of Psychiatry. 8 (31 Pt 3): 375–85. doi:10.1177/0957154X9700803104. PMID 11619584.

Further reading

- Bibliography of scholarly histories on schizophrenia and dementia praecox, part 1 (2000 – mid 2007).

- Burgmair, Wolfgang & Eric J. Engstrom & Matthias Weber, et al., eds. Emil Kraepelin. 8 vols. Munich: Belleville, 2000–2013.

- Vol. VIII. Kraepelin in München, Teil III: 1921–1926 (2013), ISBN 978-3-943157-22-2.

- Vol. VII: Kraepelin in München, Teil II: 1914–1926 (2008).

- Vol. VI: Kraepelin in München, Teil I: 1903–1914 (2006), ISBN 3-933510-95-3

- Vol. V: Kraepelin in Heidelberg, 1891–1903 (2005), ISBN 3-933510-94-5

- Vol. IV: Kraepelin in Dorpat, 1886–1891 (2003), ISBN 3-933510-93-7

- Vol. III: Briefe I, 1868–1886 (2002), ISBN 3-933510-92-9

- Vol. II: Kriminologische und forensische Schriften: Werke und Briefe (2001), ISBN 3-933510-91-0

- Vol. I: Persönliches, Selbstzeugnisse (2000), ISBN 3-933510-90-2

- Engels, Huub (2006). Emil Kraepelins Traumsprache 1908–1926. annotated edition of Kraepelin's dream speech in the mentioned period. ISBN 978-90-6464-060-5.

- Kraepelin, Emil. Psychiatrie: Ein kurzes Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. Vierte, vollstandig umgearbeitete Auflage. Leipzig: Abel Verlag, 1893.

- Kraepelin, Emil. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. Funfte, vollstandig umgearbeitete Auflage. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1896.

- Kraepelin, Emil. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studirende und Aerzte. Sechste, vollstandig umgearbeitete Auflage. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1899.

- Pick, Arnold. Ueber primare chronische Demenz (so. Dementia praecox) im jugendlichen Alter. Prager medicinische Wochenschrift, 1891, 16: 312–315.

See also

- Daniel Paul Schreber, a famous case of dementia praecox.