Diablo Range

| Diablo Range | |

|---|---|

The Diablo Range in the vicinity of San Benito Mountain | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,597 m (5,240 ft) |

| Geography | |

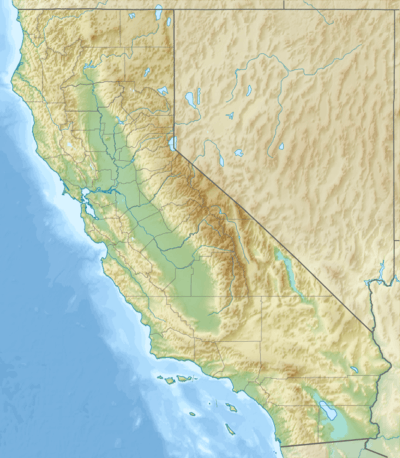

Location of the Diablo Mountain Range in California, U.S.[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Central California |

| Range coordinates | 36°22′11″N 120°38′39″W / 36.3697°N 120.6443°WCoordinates: 36°22′11″N 120°38′39″W / 36.3697°N 120.6443°W |

| Topo map | USGS San Benito Mountain |

The Diablo Range is a mountain range in the California Coast Ranges subdivision of the Pacific Coast Ranges. It is located in the eastern San Francisco Bay area south to the Salinas Valley area of northern California, the United States.

Geography

The Diablo Range extends from the Carquinez Strait in the north to Orchard Peak in the south, near the point where State Route 46 crosses over the Coast Ranges at Cholame, as described by the USGS. It is bordered on the northeast by the San Joaquin River, on the southeast by the San Joaquin Valley, on the southwest by the Salinas River, and on the northwest by the Santa Clara Valley.[1] The USGS designation is somewhat ambiguous north of the Santa Clara Valley, but on their maps, the range is shown as the ridgeline which runs between its namesake Mount Diablo southeastward past Mount Hamilton. Geologically, the range corresponds to the California Coast Ranges east of the Calaveras Fault in this northern section.

For much of the length of the Diablo Range, it is paralleled by other sections of the California Coast Ranges to the west, the Santa Cruz Mountains across the southern San Francisco Bay and Santa Clara Valley, and the Santa Lucia Range across the Salinas Valley.

The range passes through Contra Costa, Alameda, San Joaquin, Santa Clara, Stanislaus, Merced, San Benito, Fresno, Monterey, and Kings Counties, and ends in the northwesternmost extremity of Kern County.

Topography

Though the average elevation is about 3,000 feet (910 m), a summit at over 2,300 feet (700 m) is considered high, mainly because the range is mostly rolling grasslands and plateaus, punctuated by sudden peaks. The plateaus are usually at about 2,000–3,000 feet (610–910 m). The hills (not including foothills) rising out of valleys rise to about 1,000 feet (300 m) at most, and the hills rolling around inland plateaus go from 1,500–2,500 feet (460–760 m). Foothills, such as the which are found near the Santa Clara Valley, Livermore Valley and San Joaquin Valley, are lowest, from 400–1,000 feet (120–300 m).

Canyons usually are 300–400 feet (91–122 m) deep and valleys are deeper but gentler. The peaks often have high topographic prominence because they are typically surrounded by hills, valleys, or lower plateaus. Some streams draining the eastern slopes of the Diablo Range include Alameda Creek, Coyote Creek (Santa Clara County), Hospital Creek, and Ingram Creek.

Peaks

The Diablo Range's following peaks and ridges are between 2,517–5,241 feet (767–1,597 m) and are distinct landmarks. Mount Diablo (3,889 feet (1,185 m)), San Benito Mountain (5,241 feet (1,597 m)), Mount Hamilton Ridge (4,230–4,260 feet (1,290–1,300 m)), and Mount Stakes (3,804 feet (1,159 m)).

Human elements

The Diablo Range is paralleled for much of its distance by U.S. Route 101 to the west and by I-5 to the east.

Major routes of travel through the range include:

- North of the range

- Willow Pass (State Route 4)

- Altamont Pass

- Pacheco Pass

- State Route 198

- Cottonwood Pass (State Route 41)

- Polonio Pass (State Route 46)

A sparsely used gravel road is the highest road in the range, with its highest point being on San Benito Mountain at over 5,000 feet.

The Diablo Range is largely unpopulated outside of the San Francisco Bay Area. Major nearby communities include Antioch, Concord, Walnut Creek, San Ramon, Pleasanton, Livermore, Fremont and the Central Valley city of Tracy.

In the South Bay, communities near (though not in) the range are Milpitas, eastern San Jose, Morgan Hill, and Gilroy. South of Pacheco Pass, the only major nearby communities (those with a population over 15,000) are Los Baños, and Hollister. The small town of Coalinga may also be notable for its location on State Route 198, one of the few routes through the mountains.

Parks

Most of the range consists of private ranchland, limiting recreational use. However, the range does contain several areas of parkland, including Mount Diablo State Park, Alum Rock Park, Grant Ranch Park, Henry W. Coe State Park, Laguna Mountain Recreation Area, and the BLM's Clear Creek Management Area. In addition, some private land is held in conservation easements by the California Rangeland Trust.

Natural history

Since the range lies around 10 to 50 miles (16 to 80 km) inland from the ocean, and other coastal ranges like the Santa Lucia Range and the Santa Cruz Mountains block incoming moisture, the range gets little precipitation. In addition, the average elevation of 3,000 feet is not high enough to catch most of the incoming moisture at higher altitudes.

Winters are mild with moderate rainfall, but summers are very dry and hot. Areas above 2,500 feet (762 m) get light to moderate snow in the winter, especially at the highest point, the 5,241 ft (1,597 m) San Benito Mountain in the remote southeastern section of the range. However, though sites at the lower end get annual snowfall, it is typically light and melts too fast to be noticed. Once or twice a decade there is seriously deep and long lasting snowfall.

Mercury contamination near the southern end of the range is an ongoing problem, thanks to the New Idria quicksilver mines, which stopped production in the 1970s. Heavy mercury contamination has been documented in the San Carlos and Silver Creeks, which flow into Panoche Creek, and thence into the San Joaquin River. This has resulted in mercury contamination all the way downstream to the San Francisco Bay. Silver and San Carlos creeks provide a wetland environment in an otherwise arid region and are important for the ecology of the region. As of 2011, New Idria has been listed as a Superfund site and scheduled for cleanup.[2]

Flora

The Diablo Range is part of the California interior chaparral and woodlands ecoregion. It is covered mostly by chaparral and California oak woodland communities, with stands of closed-cone pine forests appearing above 4,000 feet (1,219 m). The native bunch grass savanna has been predominantly replaced by annual Mediterranean grasses, except in some rare habitat fragments. The understory is dominated with nonnative invasives. Blooming in spring are such plants as Viola pedunculata, Dodecatheon pulchellum, Fritillaria liliacea, and Ribes malvaceum, which can be viewed in the Blue Oak Ranch Reserve.[3]

The range's riparian zones have such trees as bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), white alder (Alnus rhombifolia), California bay (Umbellularia californica), and California sycamore (Platanus racemosa).[4]

The most common trees are coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) and blue oak (Quercus douglasii), with the largest blue oak growing in Alameda County. There are also good populations of California buckeye (Aesculus californica), and California black oak (Quercus kelloggii). The gray pine (Pinus sabiniana) and rarer Coulter pine (Pinus coulteri) can be found at all elevations, especially between 800 ft. and 3000 ft. Coulter pine reaches its northern limit on northern of Mt. Diablo. The conifers at higher elevations in the Diablo Range include knobcone pine (Pinus attenuata) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa).

Fauna

The Diablo Range attracts far more raptors than coastal forests, such as red tail hawks. Golden eagle nesting sites are found[5] in the Diablo Range, reaching their highest density in southern Alameda County.[6][7][8]

The Bay checkerspot butterfly, a federally listed threatened species, has habitat in the Range, especially at Mount Diablo. The California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense), also a federally threatened species and a vulnerable species of amphibian native to Northern California, lives in ponds in the range.[9] The northern Pacific rattlesnake is thriving, as are many ground squirrels, hares, and various species of native and nonnative rodents.

Tule elk (Cervus canadensis ssp. nannodes) were restored to Mount Hamilton between 1978-1981 and are slowly recovering in several small herds in Santa Clara and Alameda Counties. See Mount Hamilton elk recovery. Black-tailed deer are abundant. Pronghorn, grizzly bears, and wolves were extirpated in the 1800s. There still are numerous coyotes and some of the more vital mountain lion populations in the state. There are excellent populations of bobcats and gray foxes, who depend on the chaparral habitat.

A species of millipede, Illacme plenipes, is endemic to the southern Diablo Range. First described in 1926, then not seen again until 2005, the species has more legs than any other species of millipede, with one specimen having 750.[10]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diablo Range. |

- Mount Diablo

- Mountain ranges of the San Francisco Bay Area

- Rancho Cañada de Pala

- Rancho Santa Teresa

References

- 1 2 "Diablo Range". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ New Idria Mercury Mine, EPA

- ↑ http://www.blueoakranchreserve.org/BORR/Galleries/Galleries.html . accessed 6/28/2010

- ↑ http://www.blueoakranchreserve.org/BORR/Galleries/Pages/Habitat_Highlights%3A_The_Arroyo_Hondo_Survey.html . accessed 6/28/2010

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Paul Hoffey et al. al., Environmental Impact Report for the Aiassa Site off Mount Hamilton Road, Santa Clara County, Ca., Santa Clara County Document EMI 7364W1 SCH88071916, August, 1989

- ↑ Peterson, Hans- Raptors of California

- ↑ Fatal Attraction: Birds and Wind Turbines | QUEST. Kqed.org (2007-06-26). Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ↑ Cool Critters: The Golden Eagle | QUEST. Kqed.org (2009-07-28). Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ↑ http://www.blueoakranchreserve.org/BORR/Galleries/Pages/Species_Highlights%3A_The_California_Tiger_Salamander.html . accessed 6/28/2010

- ↑ 666-Legged Creature Rediscovered. LiveScience (2006-06-07). Retrieved on 2013-07-21.