Dick Turpin

| Richard "Dick" Turpin | |

|---|---|

|

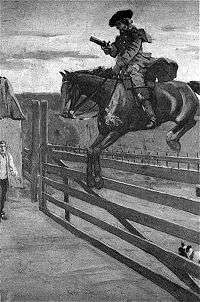

As imagined in William Harrison Ainsworth's novel Rookwood | |

| Born |

Richard Turpin bapt. 21 September 1705 Hempstead, Essex |

| Died |

7 April 1739 (aged 33) Knavesmire, York |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Other names | John Palmer |

| Occupation | Butcher, poacher, burglar, horse thief, highwayman |

| Criminal charge | Horse theft |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Millington |

| Children | One (uncertain)[1][2] |

| Parent(s) |

John Turpin Mary Elizabeth Parmenter |

| Conviction(s) | Guilty |

Richard "Dick" Turpin (bapt. 1705 – 7 April 1739) was an English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. Turpin may have followed his father's trade as a butcher early in life, but, by the early 1730s, he had joined a gang of deer thieves and, later, became a poacher, burglar, horse thief and killer. He is also known for a fictional 200-mile (320 km) overnight ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess, a story that was made famous by the Victorian novelist William Harrison Ainsworth almost 100 years after Turpin's death.

Turpin's involvement in the crime for which he is most closely associated—highway robbery—followed the arrest of the other members of his gang in 1735. He then disappeared from public view towards the end of that year, only to resurface in 1737 with two new accomplices, one of whom he may have accidentally shot and killed. Turpin fled from the scene and shortly afterwards killed a man who attempted his capture. Later that year, he moved to Yorkshire and assumed the alias of John Palmer. While he was staying at an inn, local magistrates became suspicious of "Palmer" and made enquiries as to how he funded his lifestyle. Suspected of being a horse thief, "Palmer" was imprisoned in York Castle, to be tried at the next assizes. Turpin's true identity was revealed by a letter he wrote to his brother-in-law from his prison cell, which fell into the hands of the authorities. On 22 March 1739, Turpin was found guilty on two charges of horse theft and sentenced to death; he was executed on 7 April 1739.

Turpin became the subject of legend after his execution, romanticised as dashing and heroic in English ballads and popular theatre of the 18th and 19th centuries and in film and television of the 20th century.

Early life

Richard "Dick" Turpin was born at the Blue Bell Inn (later the Rose and Crown) in Hempstead, Essex, the fifth of six children to John Turpin and Mary Elizabeth Parmenter. He was baptised on 21 September 1705, in the same parish where his parents had been married more than ten years earlier.[3]

Turpin's father was a butcher and inn-keeper. Several stories suggest that Dick Turpin may have followed his father into these trades; one hints that as a teenager he was apprenticed to a butcher in the village of Whitechapel, while another proposes that he ran his own butcher's shop in Thaxted. Testimony from his trial in 1739 suggests that he had a rudimentary education and, although no records survive of the date of the union,[4] that in about 1725 he married Elizabeth Millington.[nb 1] Following his apprenticeship they moved north to Buckhurst Hill, Essex, where Turpin opened a butcher's shop.[3]

Essex gang

Turpin most likely became involved with the Essex gang of deer thieves in the early 1730s. Deer poaching had long been endemic in the Royal Forest of Waltham, and in 1723 the Black Act (so called because it outlawed the blackening or disguising of faces while in the forests) was enacted to deal with such problems.[6] Deer stealing was a domestic offence that was judged not in civil courts, but before Justices of the peace; it was not until 1737 that the more severe penalty of seven years' transportation was introduced.[7] However, in 1731 seven verderers became so concerned by the increase in activity that they signed an affidavit which demonstrated their worries. The statement was lodged with Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle, who responded by offering a £10 reward to anyone who helped identify the thieves, plus a pardon for those thieves who gave up their colleagues. Following a series of nasty incidents, including the threatened murder of a keeper and his family, in 1733 the government increased the reward to £50 (about £7,100 as of 2016).[8][9]

The Essex gang (sometimes called the Gregory Gang), which included Samuel Gregory, his brothers Jeremiah and Jasper, Joseph Rose, Mary Brazier (the gang's fence), John Jones, Thomas Rowden and a young John Wheeler,[10] needed contacts to help them to dispose of the deer. Turpin, a young butcher who traded in the area, almost certainly became involved with their activities. By 1733 the changing fortunes of the gang may have prompted him to leave the butchery trade, and he became the landlord of a public house, most likely the Rose and Crown at Clay Hill. Although there is no evidence to suggest that Turpin was directly involved in the thefts, by summer 1734 he was a close associate of the gang, which may indicate that he had been known to them for some time.[11]

By October 1734 several in the gang had either been captured or had fled,[12] and the remaining members moved away from poaching, raiding the home of a chandler and grocer named Peter Split, at Woodford.[nb 2] Although the identities of the perpetrators are unknown, Turpin may have been involved.[nb 3] Two nights later they struck again, at the Woodford home of a gentleman named Richard Woolridge, a Furnisher of Small Arms in the Office of Ordnance at the Tower of London. In December Jasper and Samuel Gregory, John Jones, and John Wheeler, attacked the home of John Gladwin (a higler) and John Shockley, in Chingford.[15] On 19 December Turpin and five other men raided the home of Ambrose Skinner, a 73-year-old farmer from Barking, leaving with an estimated £300.[16]

Two days later, the gang—minus Turpin—attacked the home of a Keeper, William Mason, at Epping Forest. During the robbery Mason's servant managed to escape, and returned about an hour later with several neighbours, by which time the house was ransacked and the thieves long gone.[17] On 11 January 1735 the gang raided the Charlton home of a Mr. Saunders.[18] For the robbery of a gentleman named Sheldon, one week later at Croydon, Turpin arrived masked and armed with pistols, with four other members of the gang. In the same month two men, possibly from the same gang, raided the home of a Reverend Dyde. The clergyman was absent but the two cut his manservant around the face "in a barbarous manner". Another brutal attack occurred on 1 February 1735 at Loughton:[16]

On Saturday night last, about seven o'clock, five rogues entered the house of the Widow Shelley at Loughton in Essex, having pistols &c. and threatened to murder the old lady, if she would not tell them where her money lay, which she obstinately refusing for some time, they threatened to lay her across the fire, if she did not instantly tell them, which she would not do. But her son being in the room, and threatened to be murdered, cried out, he would tell them, if they would not murder his mother, and did, whereupon they went upstairs, and took near £100, a silver tankard, and other plate, and all manner of household goods. They afterwards went into the cellar and drank several bottles of ale and wine, and broiled some meat, ate the relicts of a fillet of veal &c. While they were doing this, two of their gang went to Mr Turkles, a farmer's, who rents one end of the widow's house, and robbed him of above £20 and then they all went off, taking two of the farmer's horses, to carry off their luggage, the horses were found on Sunday the following morning in Old Street, and stayed about three hours in the house.

The gang lived in or around London. For a time Turpin stayed at Whitechapel, before moving to Millbank.[20] On 4 February 1735 he met John Fielder, Samuel Gregory, Joseph Rose, and John Wheeler, at an inn along The Broadway in London. They planned to rob the house of Joseph Lawrence, a farmer at Earlsbury Farm in Edgware. Late that afternoon, after stopping twice along the way for food and drink, they captured a shepherd boy and burst into the house, armed with pistols. They bound the two maidservants, and brutally attacked the 70-year-old farmer. They pulled his breeches around his ankles, and dragged him around the house, but Lawrence refused to reveal the whereabouts of his money. Turpin beat Lawrence's bare buttocks with his pistols, badly bruising him, and other members of the gang beat him around the head with their pistols. They emptied a kettle of water over his head, forced him to sit bare-buttocked on the fire, and pulled him around the house by his nose, and hair. Gregory took one of the maidservants upstairs and raped her. For their trouble, the gang escaped with a haul of less than £30.[21]

Three days later Turpin, accompanied by the same men along with William Saunders and Humphrey Walker, brutally raided a farm in Marylebone. The attack netted the gang just under £90. The next day the Duke of Newcastle offered a reward of £50 in exchange for information leading to the conviction of the "several persons" involved in the two Woodford robberies, and the robberies of the widow Shelley and Reverend Dyde. On 11 February Fielder, Saunders, and Wheeler, were apprehended. Two accounts of their capture exist. One claims that on their way to rob the Lawrence household the gang had stopped at an alehouse in Edgware, and that on 11 February, while out walking, the owner noticed a group of horses outside an alehouse in Bloomsbury. He recognised these horses as those used by the same group of men who had stopped at his alehouse before the Lawrence attack, and called for the parish constable. Another account claims that two of the gang were spotted by a servant of Joseph Lawrence.[22] Regardless, the three, who were drinking with a woman (possibly Mary Brazier) were promptly arrested and committed to prison.[nb 4] Wheeler, who may have been as young as 15, quickly betrayed his colleagues, and descriptions of those yet to be captured were circulated in the press. In the London Gazette Turpin was described as "Richard Turpin, a butcher by trade, is a tall fresh coloured man, very much marked with the small pox, about 26 years of age, about five feet nine inches high, lived some time ago in Whitechapel and did lately lodge somewhere about Millbank, Westminster, wears a blue grey coat and a natural wig".[24]

Breakup of the Essex gang

Once Wheeler's confession became apparent, the other members of the gang fled their usual haunts. Turpin informed Gregory and the others of Wheeler's capture, and left Westminster.[26] On 15 February 1735, while Wheeler was busy confessing to the authorities, "three or four men" (most likely Samuel Gregory, Herbert Haines, Turpin, and possibly Thomas Rowden) robbed the house of a Mrs St. John at Chingford. On the following day Turpin (and Rowden, if present) parted company with Gregory and Haines, and headed for Hempstead to see his family. Gregory and Haines may have gone looking for Turpin, because on 17 February they stopped at an alehouse in Debden and ordered a shoulder of mutton, intending to stay for the night. However, a man named Palmer recognised them, and called for the parish constable. A fracas ensued, during which the two thieves escaped. They rejoined Turpin, and along with Jones and Rowden may have travelled to Gravesend[nb 5] before returning to Woodford.[28] Another robbery was reported at Woodford toward the end of February—possibly by Gregory and his cohorts—but with most avenues of escape cut off, and with the authorities hunting them down, the remaining members of the Essex gang kept their heads down and remained under cover, probably in Epping Forest.[29]

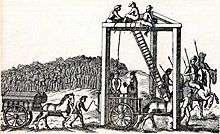

Six days after the arrest of Fielder, Saunders, and Wheeler, just as Turpin and his associates were returning from Gravesend, Rose, Brazier, and Walker were captured at a chandler's shop in Westminster, while drinking punch.[30] Fielder, Rose, Saunders and Walker were tried at the Middlesex General Session between 26 February and 1 March 1735.[31] Turpin and Gregory were also named on the indictments for burglary.[32][33] Walker died while still in Newgate Prison, but the remaining three were hanged at Tyburn gallows on 10 March, before their bodies were hung to rot in gibbets on Edgware Road. Walker's body was hung in chains.[34] Two days before the hanging, a report of "four suspicious men" being driven away from an alehouse at East Sheen appeared in a newspaper, and was likely describing Gregory and his companions,[35] but the remaining members of the Essex gang were not reported again until 30 March, when three of them (unsuccessfully) tried to steal a horse from a servant of the Earl of Suffolk. Turpin was present with four of the gang at another robbery, reported on 8 March.[36] Jasper Gregory meanwhile was captured, and then executed late in March. His brothers were arrested on 9 April[37] in Rake, West Sussex, after a struggle during which Samuel lost the tip of his nose to a sword, and Jeremy was shot in the leg. He died in Winchester gaol; Samuel was tried in May,[38] and executed on 4 June. His body was later moved, to hang in chains alongside those of his colleagues at Edgware. Mary Brazier was transported to the Thirteen Colonies.[39] Herbert Haines was captured on 13 April, and executed in August.[40] John Wheeler, who had been instrumental in proving the cases against his former colleagues, and who was freed, died at Hackney in January 1738. The reason for his death is not recorded, but is assumed to be natural causes.[41]

Highwayman

With the Essex gang now smashed by the authorities, Turpin turned instead to the crime he became most noted for — highway robbery. Although he may have been involved in earlier highway robberies on 10 and 12 April,[37] he was first identified as a suspect in one event on 10 July, as "Turpin the butcher", along with Thomas Rowden, "the pewterer". Several days later the two struck at Epping Forest, depriving a man from Southwark of his belongings. With a further bounty of £100 on their heads they continued their activities through the latter half of 1735. In August they robbed five people accompanying a coach on Barnes Common, and shortly after that they attacked another coach party, between Putney and Kingston Hill. On 20 August the pair relieved a Mr Godfrey of six guineas and a pocket book, on Hounslow Heath. Fearing capture, they moved on to Blackheath in Hertfordshire, and then back to London.[42] On 5 December the two were seen near Winchester, but in late December, following the capture of John Jones, they separated.[43] Rowden had previously been convicted of counterfeiting, and in July 1736 he was convicted of passing counterfeit coin, under the alias Daniel Crispe.[44] Crispe's true name was eventually discovered and he was transported in June 1738.[41] Jones also suffered transportation, to the Thirteen Colonies.[39]

[...] King immediately drew a Pistol, which he clapp'd to Mr Bayes's Breast; but it luckily flash'd in the Pan; upon which King struggling to get out his other, it had twisted round his pocket and he could not. Turpin, who was waiting not far off on Horseback, hearing a Skirmish came up, when King cried out, Dick, shoot him, or we are taken by G—d; at which Instant Turpin fir'd his Pistol, and it mist Mr. Bayes, and shot King in two Places, who cried out, Dick, you have kill'd me; which Turpin hearing, he rode away as hard as he could. King fell at the Shot, though he liv'd a Week after, and gave Turpin the Character of a Coward [...]

Richard Bayes[45]

Little is known of Turpin's movements during 1736. He may have travelled to Holland, as various sightings were reported there, but he may also have assumed an alias and disappeared from public view. In February 1737 though, he spent the night at Puckeridge, with his wife, her maid and a man called Robert Nott.[46] Turpin arranged the meeting by letter, which was intercepted by the authorities.[47] While Turpin eluded his enemies, making his escape to Cambridge, the others were arrested on charges of "violent suspicion of being dangerous rogues and robbing upon the highway". They were imprisoned at Hertford gaol, although the women were later acquitted (Nott was released at the next Assize). Although one report late in March suggests, unusually, that Turpin alone robbed a company of higlers, in the same month he was reported to be working alongside two other highwaymen, Matthew King (then, and since, incorrectly identified as Tom King), and Stephen Potter. The trio were responsible for a string of robberies between March and April 1737,[48] which ended suddenly in an incident at Whitechapel, after King (or Turpin, depending upon which report is read) had stolen a horse near Waltham Forest. Its owner, Joseph Major, reported the theft to Richard Bayes, landlord of the Green Man public house at Leytonstone. Bayes (who later wrote a biography of Turpin), tracked the horse to the Red Lion at Whitechapel. Major identified the animal, but as it was late evening and the horses had not yet been collected by their "owners", they elected to hold a vigil. John King (Matthew King's brother) arrived late that night, and was quickly apprehended by the party, which included the local constable. John King told him the whereabouts of Matthew King, who was waiting nearby.[nb 6][49] During the resulting mêlée, King was wounded by gunfire,[46] and died on 19 May.[50] Potter was later caught, but at his trial was released for lack of evidence against him.[51]

Fatal shooting

Bayes' statement regarding the death of Matthew King may have been heavily embellished. Several reports, including Turpin's own account,[52] offer different versions of what actually happened on that night early in May 1737; early reports claimed that Turpin had shot King, however by the following month the same newspapers retracted this claim, and stated that Bayes had fired the fatal shot.[53] The shooting of King, however, preceded an event that changed Turpin's life completely. He escaped to a hideaway in Epping Forest, where he was seen by Thomas Morris, a servant of one of the Forest's Keepers. Turpin shot and killed Morris on 4 May with a carbine when, armed with pistols, Morris attempted to capture him.[54] The shooting was reported in The Gentleman's Magazine:

It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, Servant to Henry Tomson, one of the Keepers of Epping-Forest, and commit other notorious Felonies and Robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious Pardon to any of his Accomplices, and a Reward of 200l. to any Person or Persons that shall discover him, so as he may be apprehended and convicted. Turpin was born at Thacksted in Essex, is about Thirty, by Trade a Butcher, about 5 Feet 9 Inches high, brown Complexion, very much mark'd with the Small Pox, his Cheek-bones broad, his Face thinner towards the Bottom, his Visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the Shoulders.— The Gentleman's Magazine (June 1737), [55]

Several newspapers suggested that on 6 and 7 May, he committed two highway robberies near Epping.[nb 7] Turpin may also have lost his mount; on 7 May an Elizabeth King attempted to secure two horses left by Matthew King, at an inn called the Red Lion. The horses were suspected as belonging to "highwaymen" and King was arrested for questioning, but was later released without charge. Morris's killing unleashed a flood of Turpin reports, and a reward of £200 was offered for his capture.[56]

As John Palmer

Sometime around June 1737 Turpin boarded at the Ferry Inn at Brough, under the alias of John Palmer (or Parmen). Travelling across the River Humber between the historic counties of the East Riding of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, he posed as a horse trader, and often hunted alongside local gentlemen. On 2 October 1738 Turpin shot another man's game cock in the street. While being rebuked by John Robinson, he then threatened to shoot him also. Three East Riding justices (JP), George Crowle (Member of Parliament for Hull), Hugh Bethell, and Marmaduke Constable, travelled to Brough and took written depositions about the incident. They threatened to bind him over, but Turpin refused to pay the required surety, and was committed to the House of Correction at Beverley. Turpin was escorted to Beverley by the parish constable, Carey Gill.[57] Incomprehensibly, he made no attempt at escape;[58] Barlow (1973) surmises that at this point in his life, Turpin may have been wallowing in self-pity, depressed that his life had thus far been a failure.[59]

Robert Appleton, Clerk of the Peace for the East Riding, and the man whose account details the above incident, later reported that the three JPs made enquiries as to how "Palmer" had made his money, suspecting that his lifestyle was funded by criminal activities. Turpin claimed that he was a butcher who had fallen into debt, and that he had levanted from his home in Long Sutton, Lincolnshire. When contacted, the JP at Long Sutton (a Mr Delamere) confirmed that John Palmer had lived there for about nine months,[60] but that he was suspected of stealing sheep, and had escaped the custody of the local constable. Delamere also suspected that Palmer was a horse-thief and had taken several depositions supporting his view, and told the three JPs that he would prefer him to be detained.[60] The three JPs now presumed that the case was too serious for Palmer to remain at Beverley House of Correction, and demanded sureties for his appearance at York Assizes. Turpin refused, and so on 16 October he was transferred to York Castle in handcuffs.[61]

Horse theft became a capital offence in 1545, punishable by death.[62] During the 17th and 18th centuries, crimes in violation of property rights were some of the most severely punished; most of the 200 capital statutes were property offences.[63] Robbery combined with violence was "the sort of offence, second only to premeditated murder (a relatively uncommon crime), most likely to be prosecuted and punished to [the law's] utmost rigour".[64][nb 8] Turpin had stolen several horses while operating under the pseudonym of Palmer. In July 1737 he stole a horse from Pinchbeck in Lincolnshire, and took it to visit his father at Hempstead. When Turpin returned to Brough (stealing three horses along the way) he left the gelding with his father. The identity of John Turpin's son was well known, and the horse's identity was soon discovered. On 12 September 1738 therefore, John Turpin was committed to gaol in Essex on charges of horse theft, but following his help in preventing a jailbreak, the charges were dropped on 5 March 1739. About a month after "Palmer" had been moved to York Castle,[60] Thomas Creasy, the owner of the three horses stolen by Turpin, managed to track them down and recover them, and it was for these thefts that he was eventually tried.[66]

From his cell, Turpin wrote to his brother-in-law, Pompr Rivernall, who also lived at Hempstead. Rivernall was married to Turpin's sister, Dorothy. The letter was kept at the local post office, but seeing the York post stamp Rivernall refused to pay the delivery charge, claiming that he "had no correspondent at York". Rivernall may not have wanted to pay the charge for the letter, or he may have wished to distance himself from Turpin's affairs, and so the letter was moved to the post office at Saffron Walden where James Smith, who had taught Turpin how to write while the latter was at school, recognised the handwriting. He alerted JP Thomas Stubbing, who paid the postage and opened the letter. Smith travelled to York Castle and on 23 February identified Palmer as Turpin.[67] He received the £200 (about £29,000 as of 2016)[8] reward originally offered by the Duke of Newcastle following Turpin's murder of Thomas Morris.[68]

Trial

a great concourse of people flock to see him, and they all give him money. He seems very sure that nobody is alive that can hurt him [...]

Anonymous letter, General Evening Post (8 March 1739)[69]

Although there was some question as to where the trial should be held—the Duke of Newcastle wanted him tried in London—Turpin was tried at York Assizes.[71] Proceedings began three days after the winter Assizes opened, on 22 March. Turpin was charged with the theft of Creasy's horses: a mare worth three pounds, a foal worth 20 shillings, and a gelding worth three pounds. The indictments stated that the alleged offences had occurred at Welton on 1 March 1739, and described Turpin as "John Palmer alias Pawmer alias Richard Turpin ... late of the castle of York in the County of York labourer".[nb 9] Technically the charges were invalid—the offences had occurred at Heckington, not Welton, and the date was also incorrect; the offences were in August 1738.[72]

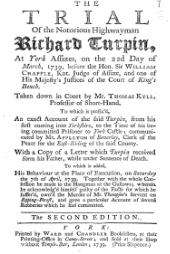

Presiding over the trial was Sir William Chapple, a senior and respected judge in his early sixties. The prosecution was directed by King's Counsel Thomas Place and Richard Crowle (brother of George), and proceedings were recorded by a York resident, Thomas Kyll. Turpin had no defence barrister; during this period of English history, those accused had no right to legal representation, and their interests were cared for by the presiding judge. Among the seven witnesses called to testify were Thomas Creasy, and James Smith, the man who had recognised Turpin's handwriting. Turpin offered little in the way of questioning his accusers; when asked if he had anything to ask of Creasy, he replied "I cannot say anything, for I have not any witnesses come this day, as I have expected, and therefore beg of your Lordship to put off my trial 'till another day", and when asked about Smith, he claimed not to know him. When questioned himself, Turpin told the court that he had bought the mare and foal from an inn-keeper near Heckington. He repeated his original story of how he had come to use the pseudonym Palmer, claiming that it was his mother's maiden name. When asked by the judge for his name before he came to Lincolnshire, he said "Turpin".[73] Without leaving the courtroom the jury found Turpin guilty of the first charge of stealing the mare and foal, and following further proceedings, guilty of stealing the gelding.[74] Throughout the trial Turpin had repeatedly claimed that he had not been allowed enough time to form his defence, that proceedings should be delayed until he could call his witnesses, and that the trial should be held at Essex. Before sentencing him, the judge asked Turpin if he could offer any reason why he should not be sentenced to death; Turpin said: "It is very hard upon me, my Lord, because I was not prepar'd for my Defence." The judge replied: "Why was you not? You knew the Time of the Assizes as well as any Person here." Despite Turpin's pleas that he had been told the trial would be held in Essex, the judge replied: "Whoever told you so were highly to blame; and as your country have found you guilty of a crime worthy of death, it is my office to pronounce sentence against you",[1] sentencing him to death.[75]

Execution

Before his execution, Turpin frequently received visitors (the gaoler was reputed to have earned £100 from selling drinks to Turpin and his guests),[77] although he refused the efforts of a local clergyman who offered him "serious remonstrances and admonitions".[78] John Turpin may have sent his son a letter,[nb 10] dated 29 March, urging him to "beg of God to pardon your many transgressions, which the thief upon the cross received pardon for at the last hour".[80] Turpin bought a new frock coat and shoes, and on the day before his execution hired five mourners for three pounds and ten shillings (to be shared between them). On 7 April 1739, followed by his mourners, Turpin and John Stead (a horse thief) were taken through York by open cart to Knavesmire, which was then the city's equivalent of London's Tyburn gallows. Turpin "behav'd himself with amazing assurance", and "bow'd to the spectators as he passed".[81] He climbed a ladder to the gallows and spoke to his executioner. York had no permanent hangman, and it was the custom to pardon a prisoner on condition that he acted as executioner. On this occasion, the pardoned man was a fellow highwayman, Thomas Hadfield.[76] An account in The Gentleman's Magazine for 7 April 1739 notes Turpin's brashness: "Turpin behaved in an undaunted manner; as he mounted the ladder, feeling his right leg tremble, he spoke a few words to the topsman, then threw himself off, and expir'd in five minutes."[82]

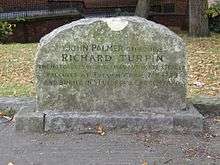

The short drop method of hanging meant that those executed were killed by slow strangulation, and so Turpin was left hanging until late afternoon, before being cut down and taken to a tavern in Castlegate.[83] The next morning, the body was buried in the graveyard of St George's Church, Fishergate, opposite what is now the Roman Catholic St George's Church. On the Tuesday following the burial, the corpse was reportedly stolen by body-snatchers. The theft of cadavers for medical research was a common enough occurrence, and was likely tolerated by the authorities in York. The practice was however unpopular with the general public, and the body-snatchers, together with Turpin's corpse, were soon apprehended by a mob. The body was recovered and reburied, supposedly this time with quicklime. Turpin's body is purported to lie in St George's graveyard, although some doubt remains as to the grave's authenticity.[84]

Modern view

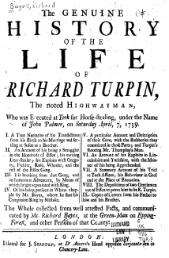

Some of the Turpin legend can be sourced directly to Richard Bayes' The Genuine History of the Life of Richard Turpin (1739), a mixture of fact and fiction hurriedly put together in the wake of the trial, to satisfy a gullible public.[85] The speeches of the condemned, biographies of criminals, and trial literature, were popular genres during the late 17th and early 18th centuries; written for a mass audience and a precursor to the modern novel, they were "produced on a scale which beggars comparison with any period before or since".[86] Such literature functioned as news and a "forum in which anxieties about crime, punishment, sin, salvation, the workings of providence and social and moral transgression generally could be expressed and negotiated."[87]

Bayes' document contains elements of conjecture; for instance, his claim that Turpin was married to a Miss Palmer (and not Elizabeth Millington) is almost certainly incorrect,[5] and the date of Turpin's marriage, for which no documentary evidence has been found, appears to be based solely on Bayes' claim that in 1739 Turpin had married 11 or 12 years earlier.[85] His account of those present during the robberies committed by the Essex Gang often contains names that never appeared in contemporary newspaper reports, suggesting, according to author Derek Barlow, that Bayes embellished his story. Bayes' description of Turpin's relationship with "King the Highwayman" is almost certainly fictional. Turpin may have known Matthew King as early as 1734,[nb 11] and had an active association with him from February 1737, but the story of the "Gentleman Highwayman" may have been created only to link the end of the Essex gang with the author's own recollection of events.[89] Barlow also views the account of the theft of Turpin's corpse, appended to Thomas Kyll's publication of 1739, as "handled with such delicacy as to amount almost to reverence", and therefore of suspect provenance.[2]

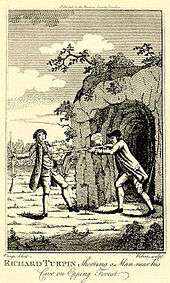

No contemporary portrait exists of Turpin, who as a notorious but unremarkable figure was not considered sufficiently important to be immortalised. An engraving in one edition of Bayes' 1739 publication, of a man hiding in a cave, is sometimes supposed to be him,[90] but the closest description that exists is that given by John Wheeler, of "a fresh coloured man, very much marked with the small pox, about five feet nine inches high ... wears a blue grey coat and a light coloured wig".[24] An E-FIT of Turpin, created from such reports, was published by the Castle Museum in York in 2009.[91]

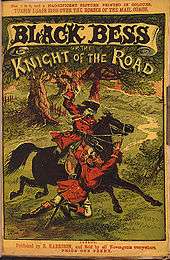

Turpin is best known for his exploits as a highwayman, but before his execution the only contemporary report of him as such was in June 1737, when a broadsheet entitled "News news: great and wonderful news from London in an uproar or a hue and cry after the Great Turpin, with his escape into Ireland" was published.[92] Although some of his contemporaries became the subject of chapbooks, names such as James Hind, Claude Duval and William Nevison, are not nearly as well-known today as the legend of Dick Turpin,[93] whose fictionalised exploits first began to appear around the turn of the 19th century. It was, however, the story of a fabled ride from London to York that provided the impetus for 19th-century author William Harrison Ainsworth to include and embellish the exploit in his 1834 novel Rookwood.[3] Ainsworth used Turpin as a plot device, describing him in a manner that makes him more lively than the book's other characters. Turpin is introduced with the pseudonym Palmer, and is later forced to escape on his horse, Black Bess. Although fast enough to keep ahead of those in pursuit, Black Bess eventually dies under the stress of the journey. This scene appealed more to readers than the rest of the work, and as Turpin was depicted as a likeable character who made the life of a criminal seem appealing, the story came to form part of the modern legend surrounding Turpin.[94] The artist Edward Hull capitalised on Ainsworth's story, publishing six prints of notable events in Turpin's career.[3]

Rash daring was the main feature of Turpin's character. Like our great Nelson, he knew fear only by name; and when he thus trusted himself in the hands of strangers, confident in himself and in his own resources, he felt perfectly easy as to the result [...] Turpin was the ultimus Romanorum, the last of a race, which—we were almost about to say we regret—is now altogether extinct. Several successors he had, it is true, but no name worthy to be recorded after his own. With him expired the chivalrous spirit which animated successively the bosoms of so many knights of the road; with him died away that passionate love of enterprise, that high spirit of devotion to the fair sex, which was first breathed upon the highway by the gay, gallant Claude Du-Val, the Bayard of the road—Le filou sans peur et sans reproche—but which was extinguished at last by the cord that tied the heroic Turpin to the remorseless tree.

Ainsworth's tale of Turpin's overnight journey from London to York on his mare Black Bess has its origins in an episode recorded by Daniel Defoe, in his 1727 work A tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain. After committing a robbery in Kent in 1676, William Nevison apparently rode to York to establish an alibi, and Defoe's account of that journey became part of folk legend.[96] A similar ride was attributed to Turpin as early as 1808, and was being performed on stage by 1819,[97] but the feat as imagined by Ainsworth (about 200 miles in less than a day) is impossible. Nevertheless, Ainsworth's legend of Black Bess was repeated in works such as Black Bess or the Knight of the Road, a 254-part penny dreadful published in 1867–68. In these tales, Turpin was the hero, accompanied by his trusty colleagues Claude Duval, Tom King, and Jack Rann. These narratives, which transformed Turpin from a pockmarked thug and murderer into "a gentleman of the road [and] a protector of the weak", followed a popular cultural tradition of romanticising English criminals.[98] This practice is reflected in the ballads written about Turpin, the earliest of which, Dick Turpin, would appear to have been published in 1737. Later ballads presented Turpin as an 18th-century Robin Hood figure: "Turpin was caught and his trial was passed, and for a game cock he died at last. Five hundred pounds he gave so free, all to Jack Ketch as a small legacy."[99]

Stories about Turpin continued to be published well into the 20th century, and the legend was also transferred to the stage. In 1845 the playwright George Dibdin-Pitt recreated the most notable "facts" of Turpin's life, and in 1846 Marie Tussaud added a wax sculpture of Turpin to her collection at Madame Tussauds.[100] In 1906 actor Fred Ginnett wrote and starred in the film Dick Turpin's Last Ride to York.[101] Other silent versions appeared for the silver screen, and some adaptations even moulded Turpin into a figure styled on Robin Hood.[102] Sid James appeared as Turpin in the 1974 Carry On film, Carry On Dick, and LWT cast Richard O'Sullivan as Turpin in their eponymous series, Dick Turpin.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Bayes' 1739 account suggests that Turpin married "the daughter of one Palmer" but Barlow (1973) suggests that this is unlikely.[5]

- ↑ Peter Split is often referred to as Peter Strype, but this mis-spelling arises from Bayes' 1739 account of the robbery.[13]

- ↑ While Turpin was on remand in York, Split was mentioned in a letter from the Duke of Newcastle to the Recorder of York, to the end that if Turpin were acquitted, he should remain in prison to stand trial for this and other robberies.[14]

- ↑ Bayes' account states that Turpin escaped through a window. According to Barlow (1973), evidence for his presence there is slight, and Bayes' account of Turpin's actions is most likely an embellishment.[23]

- ↑ A robbery at Gravesend on 17 February may have involved some members of the gang, although not Turpin, as he was with the others in Essex on that day.[27]

- ↑ The contemporary newspaper reports incorrectly identify John King as Matthew King, and Matthew King as Robert King.

- ↑ This may be unlikely; Turpin the Highwayman may have been confident enough to remain in the area, but Turpin the Murderer would, Barlow suggests, be far more likely to put as much distance between himself and the body of Morris as was possible.[56]

- ↑ Scholars have pointed out that what was called the "Bloody Code" valued property over human life, however, very few of those prosecuted for capital crimes were executed. Leniency and discretion became the heart of the English judicial system, fostering patronage and obedience to the ruling class.[65]

- ↑ "Labourer" was a catch-all, accorded to most men accused of a crime.

- ↑ Some doubt exists as to the authenticity of this letter.[79]

- ↑ One of the witnesses to the robbery of Ambrose Skinner was Elizabeth King. King was only a year or two younger than Matthew King, and may have been a relation, especially as an Elizabeth King was arrested shortly after Matthew King and Stephen Potter were apprehended.[88]

Notes

- 1 2 Kyll 1739, p. 21

- 1 2 Barlow 1973, p. 428

- 1 2 3 4 Barlow, Derek (2004), Turpin, Richard (Dick) (bapt. 1705, d. 1739) (Registration required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27892, retrieved 6 November 2009

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 109

- 1 2 Barlow 1973, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Rogers, Pat (September 1974), "The Waltham Blacks and the Black Act", The Historical Journal, 17 (3): 465–486, doi:10.1017/s0018246x00005252, JSTOR 2638385, (registration required (help))

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 18

- 1 2 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 106–109

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 115

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 3, 11

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 34

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 43

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 44

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 43–50

- 1 2 Sharpe 2005, pp. 109–113

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 58–64

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 70–72

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 78–79

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 83

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 116–119

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 111

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 113–114

- 1 2 The London Gazette: no. 7379. p. 1. 22 February 1734. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 39

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 120

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 130–131

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 126–132

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 139

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 119–123

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 145

- ↑ John Field, Joseph Rose, Theft – burglary, Violent Theft – robbery, 26th February 1735, oldbaileyonline.org, 26 February 1735, retrieved 9 November 2009

- ↑ John Field, Joseph Rose, Humphry Walker, William Bush, Theft > burglary, Violent Theft > robbery, Violent Theft > robbery, 26th February 1735, oldbaileyonline.org, 26 February 1735, retrieved 9 November 2009

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 169

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 165

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 169–170

- 1 2 Barlow 1973, p. 182

- ↑ Samuel Gregory, Theft > burglary, Violent Theft > robbery, Sexual Offences > rape, Theft > animal theft, Theft > burglary, Violent Theft > robbery, 22nd May 1735, oldbaileyonline.org, 22 March 1735, retrieved 9 November 2009

- 1 2 Sharpe 2005, pp. 123–127

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 186, p. 219

- 1 2 Sharpe 2005, p. 131

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 222–225

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 232

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 128–130

- ↑ Bayes 1739, p. 12

- 1 2 Sharpe 2005, pp. 131–134

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 258–259

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 262–264

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 272–274

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 292

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 317

- ↑ Kyll 1739, p. 25

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 274–275

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 134–135

- ↑ Urban, Sylvanus (June 1737), The Gentleman's Magazine: For JANUARY, 1737, London: E. Cave at St. John's Gate, p. 370

- 1 2 Barlow 1973, pp. 284–286

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 412

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 10–12, p. 25

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 341

- 1 2 3 Kyll 1739, p. vi

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 11–14

- ↑ Beirne 2009, pp. 40–41

- ↑ McKenzie 2007, pp. 3–4

- ↑ McKenzie 2007, p. 3

- ↑ McKenzie 2007, p. 4

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 14–17

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 19–21

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 24

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 335

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 26–27

- ↑ Kyll 1739, p. 17

- ↑ Kyll 1739, p. 17, p. 20

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 28–33

- 1 2 Sharpe 2005, p. 3

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 84

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 357

- ↑ Kyll 1739, p. viii

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Urban, Sylvanus (7 April 1739), Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, 9, London: Edw Cave, jun, at St. John's Gate, p. 7

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 7

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 33–36

- 1 2 Barlow 1973, pp. 8–9

- ↑ McKenzie 2007, pp. 31–32

- ↑ McKenzie 2007, p. 32

- ↑ Barlow 1973, p. 260

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 233–235

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, pp. 137, 143

- ↑ Wainwright, Martin (17 July 2009), Dick Turpin efit puts face to notorious name, guardian.co.uk, retrieved 3 December 2009

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 307–314

- ↑ Sharpe 2005, p. 209

- ↑ Hollingsworth 1963, pp. 101–103

- ↑ Ainsworth 1834, pp. 234–235

- ↑ Barlow 1973, pp. 442–449

- ↑ Classified Advertising, B (10767), The Times hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 3 November 1819, p. 2, retrieved 8 November 2009, (registration required (help))

- ↑ Seal 1996, p. 188

- ↑ Seal 1996, pp. 54–62

- ↑ Magnificent Addition (19417), The Times hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 11 December 1846, p. 3, column D, retrieved 8 November 2009, (registration required (help))

- ↑ Richards 1977, p. 222

- ↑ Richards 1977, p. 223

Bibliography

- Ainsworth, William Harrison (1834), Rookwood, Philadelphia: The Rittenhouse Press, hosted at gutenberg.org

- Barlow, Derek (1973), Dick Turpin and the Gregory Gang, London and Chichester: Phillimore, ISBN 0-900592-64-8

- Bayes, Richard (1739), The Genuine History of the Life of Richard Turpin, D' Anvers Head, Chancery Lane, London: J Standen

- Beirne, Piers (2009), Confronting Animal Abuse: Law, Criminology, and Human-Animal Relationships (illustrated ed.), Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-4744-2

- Hollingsworth, Keith (1963), The Newgate Novel 1830–1847, Detroit: Detroit: Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-1215-2

- Kyll, Thomas (1739), The Trial of the Notorious Highwayman Richard Turpin, London: Ward and Chandler booksellers

- McKenzie, Andrea (2007), Tyburn's Martyrs: Execution in England, 1675–1775, London: Hambledon Continuum, ISBN 1-84725-171-4

- Richards, Jeffrey (1977), Swordsmen of the screen, from Douglas Fairbanks to Michael York (illustrated ed.), London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-8478-1

- Seal, Graham (1996), The outlaw legend: a cultural tradition in Britain, America and Australia (illustrated ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55740-2

- Sharpe, James (2005), The Myth of the English Highwayman, London: Profile Books, ISBN 1-86197-418-3

External links

- 'The Real Dick Turpin'

- Review of Sharpe's book referenced above, from the London Review of Books

- A stone in Wiltshire with an inscription dedicated to Turpin

- Indictment of Dick Turpin, 1739

- The life of Dick Turpin. Devonport : S. & J. Keys. 1840. p. 8. Retrieved 28 April 2016.