Dorian mode

Dorian mode or Doric mode can refer to three very different but interrelated subjects: one of the Ancient Greek harmoniai (characteristic melodic behaviour, or the scale structure associated with it), one of the medieval musical modes, or, most commonly, one of the modern modal diatonic scales, corresponding to the white notes from D to D, or any transposition of this, for example the scale from C to C with both E and B flattened.

Greek Dorian mode

The Dorian mode (properly harmonia or tonos) is named after the Dorian Greeks. Applied to a whole octave, the Dorian octave species was built upon two tetrachords (four-note segments) separated by a whole tone, running from the hypate meson to the nete diezeugmenon. In the enharmonic genus, the intervals in each tetrachord are quarter-tone–quarter-tone–major third; in the chromatic genus, semitone-semitone-minor third; in the diatonic genus, semitone-tone-tone. In the diatonic genus, the sequence over the octave is the same as that produced by playing all the white notes of a piano ascending from E to E: E F G A | B C D E,[1] a sequence equivalent to the modern Phrygian mode. Placing the single tone at the bottom of the scale followed by two conjunct tetrachords (that is, the top note of the first tetrachord is also the bottom note of the second), produces the Hypodorian ("below Dorian") octave species: A | B C D E | (E) F G A. Placing the two tetrachords together and the single tone at the top of the scale produces the Mixolydian octave species, a note sequence equivalent to modern Locrian mode.[2]

Medieval and modern Dorian modes

Medieval Dorian mode

The early Byzantine church developed a system of eight musical modes (the octoechoi), which served as a model for medieval European chant theorists when they developed their own modal classification system starting in the 9th century.[3] The success of the Western synthesis of this system with elements from the fourth book of De institutione musica of Boethius, created the false impression that the Byzantine oktōēchos were inherited directly from ancient Greece.[4] Originally used to designate one of the traditional harmoniai of Greek theory (a term with various meanings, including the sense of an octave consisting of eight tones), the name was appropriated (along with six others) by the 2nd-century theorist Ptolemy to designate his seven tonoi, or transposition keys. Four centuries later, Boethius interpreted Ptolemy in Latin, still with the meaning of transposition keys, not scales. When chant theory was first being formulated in the 9th century, these seven names plus an eighth, Hypermixolydian (later changed to Hypomixolydian), were again re-appropriated in the anonymous treatise Alia Musica. A commentary on that treatise, called the Nova expositio, first gave it a new sense as one of a set of eight diatonic species of the octave, or scales. In medieval theory, the authentic Dorian mode could include the note B♭ "by licence", in addition to B♮.[5] The same scalar pattern, but starting a fourth or fifth below the mode final D, and extending a fifth above (or a sixth, terminating on B♭), was numbered as mode 2 in the medieval system. This was the plagal mode corresponding to the authentic Dorian, and was called the Hypodorian mode.[6] In the untransposed form on D, in both the authentic and plagal forms the note C is often raised to C♯ to form a leading tone, and the variable sixth step is in general B♮ in ascending lines and B♭ in descent.[7]

Modern Dorian mode

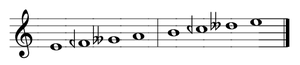

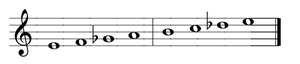

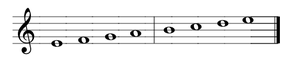

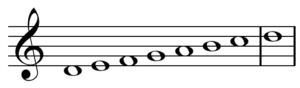

The modern Dorian mode (also called "Russian minor" by Balakirev[9]), by contrast, is a strictly diatonic scale corresponding to the white keys of the piano from "D" to "D", or any transposition of its interval pattern, which has the ascending pattern of:

or abbreviated:

Alternatively:

or

It can also be thought of as a scale with a minor third and seventh, a major second and sixth, and a perfect fourth and fifth.

It may be considered an "excerpt" of a major scale played from the pitch a whole tone above the major scale's tonic (in the key of C major it is D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D), i.e., a major scale played from its second scale degree up to its second degree again. The resulting scale is, however, minor in quality, because, as the "D" becomes the new tonal centre, the F a minor third above the D becomes the new mediant, or third degree. When a triad is built upon the tonic, it is a minor triad.

Examples of the Dorian mode include:

- The D Dorian mode, which contains all notes the same as the C major scale starting on D.

- The G Dorian mode, which contains all notes the same as the F major scale starting on G.

- The A♭ Dorian mode, which contains all notes the same as the G♭ major scale starting on A♭.

- The B Dorian mode, which contains all notes the same as the A major scale starting on B.

The Dorian mode is a symmetric scale, meaning that the pattern of whole and half notes (W-H-W-W-W-H-W) is the same ascending or descending.

The modern Dorian mode is equivalent to the natural minor scale (or the Aeolian mode) but with a major sixth. The modern Dorian mode resembles the Greek Phrygian harmonia in the diatonic genus. (The diatonic genus of the Greek Dorian harmonia resembles the modern Phrygian mode.)

The only difference between the Dorian and Aeolian scales is whether or not the sixth is major (in the Aeolian it is minor, in the Dorian it is major). The I, IV, and V triads of the Dorian mode are minor, major, and minor, respectively (i-IV-v), instead of all minor (i-iv-v) as in Aeolian. In both the Dorian and Aeolian, strictly applied, the dominant triad is minor, in contrast to the tonal minor scale, where it is normally major (see harmonic minor). Also, the sixth scale degree is often raised in minor music, just as it is often lowered in the Dorian mode (see melodic minor). The major subdominant chord gives the Dorian mode a brighter tonality than natural minor; the raised sixth is a tritone away from the minor third of the tonic. The subdominant also has a mixolydian ("dominant") quality.

The Dorian mode is harmonically similar to the ascending melodic minor scale, except for the major seventh degree in minor. This means that the dominant chord is a minor triad in the Dorian but a major one in minor keys. A second harmonic difference is the subdominant chord, which is major in the Dorian mode but minor in minor keys, because of the minor sixth scale degree. It is because of the similarity that the Dorian is also known as the jazz minor scale.

|

"The Modern Dorian Mode, in A"

An acoustic guitar playing the basic Dorian mode pattern up and down. The recording is in the key of A. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Notable compositions in Dorian mode

Traditional

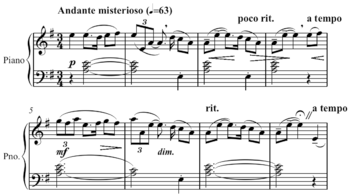

Classical

- Large portions of the Symphony No. 6 by Jean Sibelius are in the Dorian mode.[11]

- The "Et incarnatus est" in the Credo movement of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis.[12]

Jazz

- "Maiden Voyage" by Herbie Hancock[13] – The composition takes an AABBA form with the "A" sections in G Dorian and the "B" sections in A Aeolian.[14]

- "Milestones" by Miles Davis[13]

- "Oye Como Va" by Tito Puente, popularized by Santana[15]

- "So What" by Miles Davis[13] - The composition takes an AABA form with the "A" sections in D Dorian and the "B" section in E♭ Dorian.[16]

Popular

- "Born Under a Bad Sign" written by Booker T. Jones & William Bell. The song is a simple but atypical I7-V7-IV7 12-bar progression with a key signature corresponding to C♯ major but with every B♯ and E♯ lowered to B♮ and E♮, making the song C♯ Dorian.[17]

- "Eleanor Rigby" by The Beatles[18] is often cited as a Dorian modal piece, and while the melody line in places uses the major sixth scale degree, the chord progression is in Aeolian (I–♭VI and ♭VI–I).[19]

- "Wake Me Up When September Ends" by Green Day uses a Dorian vocal melody.

See also

- Kafi, the name used in Hindustani music for the equivalent scale.

- Kharaharapriya, the name used in Carnatic music for the equivalent scale.

References

- ↑ Thomas J. Mathiesen, "Greece, §I: Ancient: 6. Music Theory: (iii) Aristoxenian Tradition: (d) Scales". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ↑ Thomas J. Mathiesen, "Greece, §I: Ancient: 6. Music Theory: (iii) Aristoxenian Tradition: (e) Tonoi and Harmoniai". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001).

- ↑ Harold S. Powers, "Mode, §II: Medieval modal theory, 2: Carolingian synthesis, 9th–10th centuries", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publications; New York: Grove’s Dictionaries of Music, 2001). ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5

- ↑ Peter Jeffery, "Oktōēchos", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publications; New York: Grove’s Dictionaries of Music, 2001). ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5

- ↑ Harold S. Powers, "Dorian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publishers, 2001): 7:507. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5

- ↑ Harold S. Powers, "Hypodorian", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, 29 vols., edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell (London: Macmillan Publications, 2001): 12:36–37. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5

- ↑ Felix Salzer and Carl Schachter, Counterpoint in Composition: The Study of Voice Leading (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989): 10. ISBN 0-231-07039-X.

- ↑ Bruce Benward and Marilyn Nadine Saker, Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, eighth edition (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2009): 243–44. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ↑ Richard Taruskin, "From Subject to Style: Stravinsky and the Painters", in Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist, edited by Jann Pasler, 16–38 (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1986): 33. ISBN 0-520-05403-2.

- 1 2 Ger Tillekens, "Marks of the Dorian Family" Soundscapes, no. 5 (November 2002) (Accessed 30 June 2009).

- ↑ Lionel Pike, "Sibelius's Debt to Renaissance Polyphony", Music & Letters 55, no. 3 (July 1974): 317–26 (citation on 318–19).

- ↑ Michael Steinberg, "Notes on the Quartets", in The Beethoven Quartet Companion, edited by Robert Winter and Robert Martin, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994): 270. ISBN 978-0-520-20420-1; OCLC 27034831.

- 1 2 3 Ronald Herder, 1000 Keyboard Ideas, (Katonah, NY: Ekay Music, 1990): 75. ISBN 978-0-943748-48-1.

- ↑ Barry Dean Kernfeld, The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (New York: Macmillan Publishers, 2002): 785. ISBN 1-56159-284-6 OCLC 46956628.

- ↑ Wayne Chase, "How Keys and Modes REALLY Work". (Vancouver, BC: Roedy Black Publishing, Inc.). Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Richard Lawn and Jeffrey L. Hellmer, Jazz: Theory and Practice (Los Angeles: Alfred Publishing, 1996): 190. ISBN 0-88284-722-8.

- ↑ Transcription in "R&B Bass Bible" (Milwaukee: Hal Leonard, 2005). ISBN 0-634-08926-9.

- ↑ Alan W. Pollack. "Notes on "Eleanor Rigby"". Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Bill T. Roxler. "Thoughts on Eleanor Rigby" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-25.