Dutch Formosa

| Government of Formosa | ||||||||||

| Gouvernement Formosa | ||||||||||

| Dutch colony | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

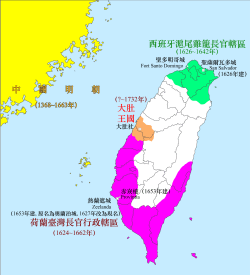

The locations of Dutch Formosa (in magenta), Kingdom of Middag (in orange) and the Spanish Possessions (in green) on Taiwan, overlapping a map of the present-day island. | ||||||||||

| Capital | Zeelandia (now Anping, Tainan) | |||||||||

| Languages | Dutch, Formosan languages, Hokkien | |||||||||

| Religion | Protestantism (Dutch Reformed Church) native animistic religion Chinese folk religion | |||||||||

| Government | Colony | |||||||||

| Governor | ||||||||||

| • | 1624–1625 | Marten Sonk | ||||||||

| • | 1656–1662 | Frederick Coyett | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Discovery | |||||||||

| • | Established | 1624 | ||||||||

| • | Siege of Fort Zeelandia | 1661–1662 | ||||||||

| • | Surrender of Fort Zeelandia | February 1, 1662 1662 | ||||||||

| Currency | Spanish real | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The island of Taiwan, known historically as Formosa, was under colonial Dutch rule from 1624 to 1662. In the context of the Age of Discovery, the Dutch East India Company established its presence on Taiwan to trade with the Ming Empire and Japan, and also to interdict Portuguese and Spanish trade and colonial activities in East Asia.

The time of Dutch rule saw economic development in Taiwan, including both large-scale hunting of deer and the cultivation of rice and sugar by imported Han labour from the Ming Empire. The Dutch also attempted to convert the aboriginal inhabitants to Christianity, and suppress aspects of traditional culture that they found disagreeable, such as head hunting, forced abortion and public nakedness.[1]

The Dutch were not universally welcomed and uprisings by both aborigines and recent Han arrivals were quelled by the Dutch military on more than one occasion. The colonial period was brought to an end by the 1661 invasion of Koxinga's army after 37 years.

History

Background

At the beginning of the 17th century, the forces of Catholic Spain and Portugal were in opposition to those of the Netherlands and England, both mainly Protestant, often resulting in open warfare in Europe and in their possessions in Asia. The Dutch first attempted to trade with China in 1601[2] but were rebuffed by the Chinese authorities, who were already engaged in trade with the Portuguese at Macau from 1535.

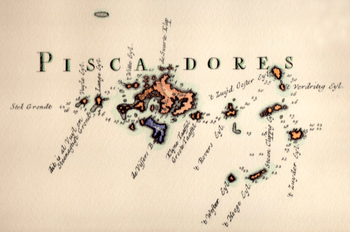

In a 1604 expedition from Batavia (the central base of the Dutch in Asia), Admiral van Warwijk set out to attack Macau, but his force was waylaid by a typhoon, driving them to the Pescadores (now known as Penghu), a group of islands 30 miles (50 km) west of Formosa (Taiwan). Once there, the admiral attempted to negotiate trade terms with the Chinese on the mainland, but was asked to pay an exorbitant fee for the privilege of an interview. Surrounded by a vastly superior Chinese fleet, he left without achieving any of his aims.[3]

The Dutch East India Company tried to use military force to make China open up a port in Fujian to trade and demanded that China expel the Portuguese, whom the Dutch were fighting in the Dutch–Portuguese War, from Macau. The Dutch raided Chinese shipping after 1618 and took junks hostage in an unsuccessful attempt to get China to meet their demands.[4][5][6]

In 1622, after another unsuccessful Dutch attack on Macau (trade post of Portugal from 1557), the fleet sailed to the Pescadores, this time intentionally, and proceeded to set up a base there at Makung. They built a fort there with forced labour recruited from the local Chinese population. Their oversight was reportedly so severe and rations so short that 1,300 of the 1,500 Chinese enslaved died in the process of construction.[7] The same year a ship named the Golden Lion (Dutch: Gouden Leeuw) was wrecked at Lamey just off the southwest coast of Formosa; the survivors were slaughtered by the native inhabitants.[8] The following year, 1623, Dutch traders in search of an Asian base first arrived on the island, intending to use the island as a station for Dutch commerce with Japan and the coastal areas of China.

The Dutch demanded that China open up ports in Fujian to Dutch trade. China refused, warning the Dutch that the Pescadores were Chinese territory. The Chinese Governor of Fujian (Fukien), Shang Zhouzuo (Shang Chou-tso), demanded that the Dutch withdraw from the Pescadores to Formosa, where the Chinese would permit them to engage in trade. This led to a war between the Dutch and China between 1622-1624 which ended with the Chinese being successful in making the Dutch abandon the Pescadores and withdraw to Formosa.[9][10] The Dutch threatened that China would face Dutch raids on Chinese ports and shipping unless the Chinese allowed trading on the Pescadores and that China not trade with Manila but only with the Dutch in Batavia and Siam and Cambodia. However, the Dutch found out that, unlike tiny Southeast Asian Kingdoms, China could not be bullied or intimidated by them. After Shang ordered them to withdraw to Formosa on September 19, 1622, the Dutch raided Amoy on October and November.[11] The Dutch intended to "induce the Chinese to trade by force or from fear." by raiding Fujian and Chinese shipping from the Pescadores.[12] Long artillery batteries were erected at Amoy in March 1622 by Colonel Li-kung-hwa as a defence against the Dutch.[13]

On the Dutch attempt in 1623 to force China to open up a port, five Dutch ships were sent to Liu-ao and the mission ended in failure for the Dutch, with a number of Dutch sailors taken prisoner and one of their ships lost. In response to the Dutch using captured Chinese for forced labor and strengthening their garrison in the Pescadores with five more ships in addition to the six already there, the new Governor of Fujian, Nan Juyi (Nan Chü-i), was permitted by China to begin preparations to attack the Dutch forces in July 1623. A Dutch raid was defeated by the Chinese at Amoy on October 1623, with the Chinese taking the Dutch commander Christian Francs prisoner and burning one of the four Dutch ships. The Chinese began an offensive in February 1624 with warships and troops against the Dutch in the Pescadores with the intent of expelling them.[14] The Chinese offensive reached the Dutch fort on July 30, 1624, with 5,000 Chinese troops (or 10,000) and 40-50 warships under General Wang Mengxiong surrounding the fort commanded by Marten Sonck, and the Dutch were forced to sue for peace on August 3 and folded before the Chinese demands, withdrawing from the Pescadores to Formosa. The Dutch admitted that their attempt at military force to coerce China into trading with them had failed with their defeat in the Pescadores. At the Chinese victory celebrations over the "red-haired barbarians," as the Dutch were called by the Chinese, Nan Juyi (Nan Chü-yi) paraded twelve Dutch soldiers who were captured before the Emperor in Beijing.[15][16][17][18] The Dutch were astonished that their violence did not intimidate the Chinese and at the subsequent Chinese attack on their fort in the Pescadores, since they thought them as timid and a "faint-hearted troupe," based on their experience with them in Southeast Asia.[19]

Early years (1624–1625)

On deciding to set up in Taiwan and in common with standard practice at the time, the Dutch built a defensive fort to act as a base of operations. This was built on the sandy peninsula of Tayouan[20] (now part of mainland Taiwan, in current-day Anping District). This temporary fort was replaced four years later by the more substantial Fort Zeelandia.[21]

Growing control, pacification of the aborigines (1626–1636)

The first order of business was to punish villages that had violently opposed the Dutch and unite the aborigines in allegiance with the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The first punitive expedition was against the villages of Bakloan and Mattau, north of Saccam near Tayowan. The Mattau campaign was easier than expected, and the tribe submitted after having their village razed by fire. The campaign also served as a threat to other villages from Tirosen (Chiayi) to Longkiau (Hengchun).

While the pacification campaign continued in Formosa, at sea, relations with the Chinese were strained by the Dutch attempts to tax ships in the Taiwan Strait. War eventually broke out between the Ming and the Dutch, and the Chinese Admiral Zheng Zhilong defeated the Dutch at the Battle of Liaoluo Bay in 1633.

Some Dutch missionaries were killed by aboriginals whom they had tried to convert: "The catechist, Daniel Hendrickx, whose name has been often mentioned, accompanied this expedition to the south, as his great knowledge of the Formosa language and his familiar intercourse with the natives, rendered his services very valuable. On reaching the island of Pangsuy, he ventured—perhaps with overweening confidence in himself— too far away from the others, and was suddenly surrounded by a great number of armed natives, who, after killing him, carried away in triumph his head, arms, legs, and other members, even his entrails, leaving the mutilated trunk behind."[22]

Pax Hollandica and the ousting of the Spanish (1636–1642)

Following the pacification campaigns of 1635–1636, more and more villages came to the Dutch to swear allegiance, sometimes out of fear of Dutch military action, and sometimes for the benefits which Dutch protection could bring (food and security). These villages stretched from Longkiau in the south (125 km from the Dutch base at Fort Zeelandia to Favorlang in central Taiwan, 90 km to the north of Fort Zeelandia. The relative calm of this period has been called the Pax Hollandica (Dutch Peace) by some commentators[23] (a reference to the Pax Romana).

One area not under their control was the north of the island, which from 1626 had been under Spanish sway, with their two settlements at Tamsui and Keelung. The fortification at Keelung was abandoned because the Spanish lacked the resources to maintain it, but Fort Santo Domingo in Tamsui was seen as a major obstacle to Dutch ambitions on the island and the region in general.

In 1642, the Dutch sent an expedition of soldiers and aboriginal warriors in ships to Tamsui, managing to dislodge the small Spanish contingent from their fortress and drive them from the island. Following this victory, the Dutch set about bringing the northern villages under their banner in a similar way to the pacification campaign carried out in the previous decade in the south.

Growing Chinese presence and the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion (1643–1659)

The Dutch began to encourage large-scale Chinese immigration to the island, mainly from Fujian. Most of the immigrants were young single males who were discouraged from staying on the island often referred to by Han as "The Gate of Hell" for its reputation in taking the lives of sailors and explorers.[24] After one uprising by Han Chinese in 1640, the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652 saw an organised insurrection against the Dutch, fuelled by anger over punitive taxes and corrupt officials. The Dutch again put down the revolt hard, with fully 25% of those participating in the rebellion being killed over a period of a couple of weeks.[23]

Aboriginal rebellions in other areas of Taiwan (1650s)

Multiple Aboriginal villages rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s due to oppression like when the Dutch ordered aboriginal women for sex, deer pelts, and rice be given to them from aborigines in the Taipei basin in Wu-lao-wan village which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. Two Dutch translators were beheaded by the Wu-lao-wan aborigines and in a subsequent fight 30 aboriginals and another two Dutch people died. After an embargo of salt and iron on Wu-lao-wan the aboriginals were forced to sue for peace on February 1653.[25]

Siege of Zeelandia and the end of Dutch government on Formosa (1660–1662)

In 1661, a naval fleet of 200 ships, led by the Ming loyalist Koxinga, landed at Lakjemuyse with the intention of ousting the Dutch from Zeelandia and making the island a base for Ming loyalists. Following a nine-month siege, Koxinga captured Zeelandia. Koxinga then forced the local representatives of the Dutch East India Company to sign a peace treaty at Zeelandia on February 1, 1662, and leave the island. From then on, the island became Koxinga's base for the Kingdom of Tungning.

Coda: The Dutch retake Keelung (1664–1668)

After being ousted from Taiwan, the Dutch allied with the new Qing dynasty in China against the Zheng regime in Taiwan. Following some skirmishes the Dutch retook the northern fortress at Keelung in 1664.[26] Zheng Jing sent troops to dislodge the Dutch, but they were unsuccessful. The Dutch held out at Keelung until 1668, when aborigine resistance (likely incited by Zheng Jing),[27] and the lack of progress in retaking any other parts of the island persuaded the colonial authorities to abandon this final stronghold and withdraw from Taiwan altogether.[28][29][30][31][32]

Government

The Dutch claimed the entirety of the island, but because of the inaccessibility of the central mountain range the extent of their control was limited to the plains on the west coast, plus isolated pockets on the east coast. This territory was acquired from 1624 to 1642, with most of the villages being required to swear allegiance to the Dutch and then largely being left to govern themselves.

The manner of acknowledging Dutch lordship was to bring a small native plant (often betel nut or coconut) planted in earth from that particular town to the Governor, signifying the granting of the land to the Dutch. The Governor would then award the village leader a robe and a staff as symbols of office and a Prinsenvlag ("Prince's Flag", the flag of William the Silent) to display in their village.

Governor of Formosa

The Governor of Formosa (Dutch: Gouverneur van Formosa; Chinese: 台灣長官) was the head of government. Appointed by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia), the Governor of Formosa was empowered to legislate, collect taxes, wage war and declare peace on behalf of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and therefore by extension the Dutch state.

He was assisted in his duties by the Council of Tayouan, a group made up of the various worthies in residence in Tayouan. The President of this council was the second-in-command to the Governor, and would take over his duties if the Governor died or was incapacitated. The Governor's residence was in Fort Zeelandia on Tayouan (then an island, now the Anping District of Tainan City). There were a total of twelve Governors during the Dutch colonial era.[33]

Economy

The Tayouan factory (as VOC trading posts were called) was to become the second-most profitable factory in the whole of the Dutch East Indies (after the post at Hirado/Dejima),[34] although it took 22 years for the colony to first return a profit.[35] Benefitting from triangular trade between themselves, the Chinese and the Japanese, plus exploiting the natural resources of Formosa, the Dutch were able to turn the malarial sub-tropical bay into a lucrative asset. A cash economy was introduced (using the Spanish real, which was used by the VOC) and the period also saw the first serious attempts in the island's history to develop it economically.[36]

Trade

The original intention of setting up Fort Zeelandia at Tayowan (Anping) in southern Formosa was to provide a base for trading with China and Japan, as well as interfering with Portuguese and Spanish trade in the region. Goods traded included silks from China and silver from Japan, among many other things.

After establishing their fortress, the Dutch realised the potential of the vast herds of the native Formosan sika deer (Cervus nippon taioanus) roaming the western plains of the island. The tough deer skins were highly prized by the Japanese, who used them to make samurai armour. Other parts of the deer were sold to Chinese traders for meat and medical use. The Dutch paid aborigines for the deer brought to them and tried to manage the deer stocks to keep up with demand. Unfortunately the deer the aborigines had relied on for their livelihoods began to disappear, forcing the aborigines to adopt new means of survival.[37] However, the subspecies was kept alive in captivity and subsequent reintroduction of the subspecies into the wild has been successful.[38]

Later the Dutch also traded in the agricultural produce of the island (including sugar and rice) after large-scale cultivation was implemented by the colonists utilising imported labour from Fujian.

Agriculture

The Dutch also employed Chinese to farm sugarcane and rice for export; some of this rice and sugar was exported as far as the markets of Persia.[39] Attempts to persuade aboriginal tribesmen to give up hunting and adopt a sedentary farming lifestyle were unsuccessful because "for them, farming had two major drawbacks: first, according to the traditional sexual division of labor, it was women's work; second, it was labor-intensive drudgery."[40]

The Dutch therefore imported labour from China, and the era was the first to see mass Chinese immigration to the island, with one commentator estimating that 50–60,000 Chinese settled in Taiwan during the 37 years of Dutch rule.[41] These settlers were encouraged with free transportation to the island, often on Dutch ships, and tools, oxen and seed to start farming.[36] In return, the Dutch took a tenth of agricultural production as a tax.[36]

Head tax

A head tax was levied on all Chinese residents over the age of six.[42] This tax was considered particularly burdensome by the Chinese as there had been no taxation prior to Dutch occupation of the island. Coupled with restrictive land tenancy policies and extortion by Dutch soldiers, the tax provided grounds for the major insurrections of 1640 and 1652.[42]

Demographics

.jpg)

Prior to the arrival of the Dutch colonists, Taiwan was almost exclusively populated by Taiwanese aborigines; Austronesian peoples who lived in a hunter-gatherer society while also practicing swidden agriculture. It is difficult to arrive at an estimate of the numbers of these native Formosans when the Dutch arrived, as there was no island-wide authority in a position to count the population, while the aborigines themselves did not keep written records. Even at the extent of greatest Dutch control in the 1650s there were still large regions of the island outside the pale of Dutch authority, meaning that any statistics given necessarily relate only to the area of Dutch suzerainty.

Ethnicity

The population of Dutch Formosa was composed of three main groups; the aborigines, the Dutch contingent, and the Chinese. There were also a number of Spanish people resident in the north of the island between 1626 and 1642 in the area around Keelung and Tamsui. At times there were also a handful of Korean-Japanese trader-pirates known as Wakō operating out of coastal areas outside Dutch control.

The Aborigines

The native Formosan peoples had been in Taiwan for thousands of years before the Dutch arrived. Estimates of the total numbers of aborigines in Taiwan are difficult to come by, but one commentator suggests that there were 150,000 over the entire island during the Dutch era. They lived in villages with populations ranging from a couple of hundred up to around 2,000 people for the biggest towns, with different groups speaking different Formosan languages which were not mutually intelligible.

The Dutch

The Dutch contingent was initially composed mostly of soldiers, with some slaves and other workers from the other Dutch colonies, particularly the area around Batavia (current day Jakarta). The number of soldiers stationed on the island waxed and waned according to the military needs of the colony, from a low of 180 troops in the early days to a high of 1,800 shortly before Koxinga's invasion. There were also a number of other personnel, from traders and merchants to missionaries and schoolteachers, plus the Dutch brought with them slaves from their other colonies, who mainly served as personal slaves for important Dutch people.

Dutch women were kept as sexual partners by the Chinese after the Dutch were expelled from Taiwan in 1662. During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia, in which Chinese Ming loyalist forces commanded by Koxinga besieged and defeated the Dutch East India Company and conquered Taiwan, the Chinese took Dutch women and children prisoner. The Dutch missionary Antonius Hambroek, two of his daughters, and his wife were among the Dutch prisoners of war with Koxinga. Koxinga sent Hambroek to Fort Zeelandia demanding that he persuade them to surrender or else Hambroek would be killed when he returned. Hambroek returned to the Fort, where two of his other daughters were. He urged the Fort not to surrender, assuring them that Koxinga's troops were growing hungry and rebellious, and returned to Koxinga's camp. He was then executed by decapitation. In addition to this, a rumor was spread among the Chinese that the Dutch were encouraging the native Taiwan aboriginals to kill Chinese, so Koxinga ordered the mass execution of Dutch male prisoners in retaliation. A few women and children were also killed. The surviving Dutch women and children were then turned into slaves. Koxinga took Hambroek's teenage daughter as a concubine;[43][44][45][46] she was described by the Dutch commander Caeuw as "a very sweet and pleasing maiden".[47] The other Dutch women were distributed to Koxinga's commanders, who used them as concubines.[48][49][50][51] The daily journal of the Dutch fort recorded that "the best were preserved for the use of the commanders, and then sold to the common soldiers. Happy was she that fell to the lot of an unmarried man, being thereby freed from vexations by the Chinese women, who are very jealous of their husbands."[52]

Some Dutch physical characteristics such as auburn and red hair among people in regions of south Taiwan are a consequence of this episode of Dutch women becoming concubines to the Chinese commanders.[53] The Dutch women who were taken as slave concubines and wives were never freed. In 1684 some were reported to be living in captivity.[54] A Dutch merchant in Quemoy was contacted with an arrangement, proposed by a son of Koxinga's, to release the prisoners, but it came to nothing.[55]

Dutch language accounts record this incident of Chinese taking Dutch women as concubines and the date of Hambroek's daughter[56][57][58][59]

The Han people

When the Dutch arrived in Taiwan there was already a network of Han traders living on the island, buying merchandise (particularly deer products) from the native Formosans. This network has been estimated at some 1,000–1,500 people, almost all male, most of whom were seasonal residents in Taiwan, returning to Fujian in the off-season.

Beginning in the 1640s the Dutch began to encourage large-scale immigration of Han people to Formosa, providing not only transportation from Fujian, but also oxen and seed for the new immigrants to get started in agriculture. Estimates of the numbers of Han people in Taiwan at the end of the Dutch era vary widely, from 10–15,000 up to 50–60,000, although the lower end of that scale seems more likely.

Others

The Dutch had Pampang and Quinamese slaves on their colony in Taiwan, and in 1643 offered rewards to aboriginal allies who would recapture the slaves for them when they ran away.[60] 18 Quinamese and Java slaves were involved in a Dutch attack against the Tammalaccouw aboriginals, along with 110 Chinese and 225 troops under Governor Traudenius on January 11, 1642.[61] 7 Quinamese and 3 Javanese were involved in a gold hunting expedition along with 200 Chinese and 218 troops under Sernior Merchant Cornelis Caesar from November 1645 to January 1646.[62] "Quinam" was the Dutch name for the Vietnamese Nguyen Lord ruled Cochinchina (which used in the 17th century to refer to the area around Quang Nam in central Vietnam, (Annam) until in 1860 the French shifted the term Cochinchina to refer to the Mekong Delta in the far south,[63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70] and Pampang was a place in Java which was ruled by the Dutch East India Company in the East Indies. The Dutch sided with the Trịnh lords of Tonkin (Northern Vietnam) against the Nguyen Lords of Quinam (Cochinchina) during the Trịnh–Nguyễn War and were therefore hostile to Quinam.[71][72][73]

Taiwanese natives under Dutch Formosa

Background

Before Dutch settlement in the seventeenth century, Taiwanese aborigines lived in numerous tribal systems uniquely autonomous of each other; with populations between a thousand and a hundred, a census conducted by Dutch colonizers in 1650 surmised that there were below 50,000 natives in the plains area. Despite temporary alliances, similar agricultural practices and few inter-marriages, there also exhibited distinct linguistic and internal structure differences of the tribes. These differences coupled with the widespread practice of head-hunting caused Formosan groups to be suspicious and cautious of strangers.[74]

Upon arrival, the first indigenous groups the Dutch made contact with were the Sinkang (新港), Backloan (目加溜灣), Soelangh (蕭), and Mattauw (麻豆). The native Taiwanese tribes’ antagonistic predispositions lead to an initial hostile relationship with the colonizers, involving several uprisings including the Hamada Yahei incident of 1628 involving the Sinkang people, and the killing of 20 Dutch soldiers in 1629 by the Mattauw tribe.[75] VOC eventually transitioned into a divide-and-conquer strategy, and went on to create an alliance with the Sinkang and Seolangh tribes against Mattauw, simultaneously conquering numerous tribes that did not comply with these commands.[76]

This interventionist process included the massacre of the indigenous people inhabiting Lamay Island in 1642 by Dutch forces led by Officer Francois Caron.[77] After these events, the native aborigines eventually were forced into pacification under military domination and were used for a variety of labor activities during the span of Dutch Formosa. According to documents in 1650, Dutch settlers ruled “315 tribal villages with a total population of around 68,600, estimated 40-50% of the entire indigenes of the island”.[78][79]

Religion

One of the key pillars of the Dutch colonial era was conversion of the natives to Christianity. From the descriptions of the early missionaries, the native religion was animist in nature, in one case presided over by priestesses called Inibs.

The Formosans also practiced various activities which the Dutch perceived as sinful or at least uncivilised, including mandatory abortion (by massage) for women under 37,[80] frequent marital infidelity,[80] non-observation of the Christian Sabbath and general nakedness. The Christian Bible was translated into native aboriginal languages and evangelised among the tribes. This marks the first recorded instance of Christianity entering into Taiwanese history, and preludes to the active Christian practices experienced in Taiwan in modern times.[78]

Education

The missionaries were also responsible for setting up schools in the villages under Dutch control, teaching not only the religion of the colonists but also other skills such as reading and writing. Prior to Dutch arrival the native inhabitants did not use writing, and the missionaries created a number of romanization schemes for the various Formosan languages. This is the first record in history of a written language in Taiwan.[81]

Experiments were made with teaching native children the Dutch language, however these were abandoned fairly rapidly after they failed to produce good results. At least one Formosan received an education in the Netherlands; he eventually married a Dutch woman and was apparently well integrated into Dutch society.[82]

Technology

The unique variety of trading resources (in particular, deerskins, venison and sugarcane), as well as the untouched nature of Formosa led to an extremely lucrative market for VOC. A journal record written by the Dutch Governor Pieter Nuyts holds that "Taiwan was an excellent trading port, enabling 100 per cent profits to be made on all goods".[83] In monopolizing on these goods, Taiwanese natives were used as manual labor, whose skills were honed in the employment on sugarcane farms and deer hunting.

Similarly, Dutch colonizers upheaved the traditional agricultural practices in favor of more modern systems. The native tribes in the field-regions were taught how to use Western systems of crop management that used more sustainable and efficient ecological technologies, albeit attributed mostly to the fact that due to the increased exploitation of the land, alternative means of management were needed to veer off the extinction of deer and sugar resources.

Military

Taiwanese aborigines became an important part of maintaining a stable milieu and eliminating conflicts during the latter half of Dutch rule. According to the Daily Journals of Fort Zeelandia (Dutch: De dagregisters van het kasteel Zeelandia), Dutch colonizers frequently employed males from nearby indigenous tribes, including Hsin-kang (新港) and Mattau (麻豆) as foot-soldiers in the general militia, to heighten their numbers when quick action was needed during rebellions or uprisings. Such was the case during that of the Guo Huaiyi Revolt in 1652, where the conspirators were eventually bested and subdued by the Dutch through the sourcing of over a hundred native Taiwanese aborigines.[76]

However, the Taiwanese Aboriginal tribes who were previously allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi Rebellion in 1652 turned against the Dutch during the later Siege of Fort Zeelandia and defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces.[84] The Aboriginals (Formosans) of Sincan defected to Koxinga after he offered them amnesty, the Sincan Aboriginals then proceeded to work for the Chinese and behead Dutch people in executions, the frontier aboriginals in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on May 17, 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under the Dutch rule by hunting down Dutch people and beheading them and trashing their Christian school textbooks.[85]

Legacy and Contributions

Today, their legacy in Taiwan is visible in Anping District of Tainan City where the remains of their Castle Zeelandia are preserved, in Tainan City itself where their Fort Provintia is still the main structure of what is now called Red-topped Tower, and finally in Tamsui where Fort Anthonio[86] (part of the Fort San Domingo museum complex) still stands as the best preserved redoubt (minor fort) of the Dutch East India Company anywhere in the world. The building was later used by the British consulate[87] until the United Kingdom severed ties with the KMT (Chinese Nationalist Party or Kuomintang) regime and its formal relationship with Taiwan.

Similarly, much of the economic policies driven by the Dutch during the colonial period were subsequently used as a basis for the beginnings of Taiwan’s modern international trade; the beginnings of Taiwan’s mercantile history and contemporary economy can be attributed to the port systems that were facilitated during the Dutch Formosa period.[76]

However, perhaps the most lasting result of Dutch rule is the immigration of Chinese to the island. At the start of the Dutch era, there were estimated to be between 1,000–1,500 Chinese in Taiwan, mostly traders living in aboriginal villages.[74] During Dutch Formosa rule, Dutch colonial policies encouraged the active immigration of Han Chinese in order to solidify the ecological and agricultural trade establishments, and help maintain control over the area. Because of these reasons, by the end of the colonial period, Taiwan had many Chinese villages holding tens of thousands of people in total, and the ethnic balance of the island was already well on the way to favouring the newly arrived Chinese over the aboriginal tribes.[23] Furthermore, Dutch settlers opened up communication between both peoples, and set about maintaining relationships with both Han Chinese and native Taiwanese – which were non-existent beforehand.[88]

See also

- History of Taiwan

- Eighty Years' War

- Fort Zeelandia

- Taiwanese aborigines: The European period

- Han Taiwanese: Influence of the Dutch language

- Dutch East India Company

- Koxinga

- Kingdom of Tungning

- Spanish Formosa

- Dutch pacification campaign on Formosa

- Landdag

Notes

- ↑ Hsu, Mutsu (1991). Culture, Self and Adaptation: The Psychological Anthropology of Two Malayo-Polynesian Groups in Taiwan. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica. ISBN 9789579046794. OCLC 555680313. OL 1328279M.

- ↑ Ts'ao (2006), p. 28.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), p. 10.

- ↑ Cooper (1979), p. 658.

- ↑ Freeman (2003), p. 132.

- ↑ Thomson (1996), p. 39.

- ↑ Davidson (1903), p. 11.

- ↑ Blussé (2000), p. 144.

- ↑ Covell (1998), p. 70.

- ↑ Wright (1908), p. 817.

- ↑ Twitchett & Mote (1998), p. 368.

- ↑ Shepherd (1993), p. 49.

- ↑ Hughes (1872), p. 25.

- ↑ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 1086.

- ↑ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 1087.

- ↑ Twitchett & Mote (1998), p. 369.

- ↑ Deng (1999), p. 191.

- ↑ Parker (1917), p. 92.

- ↑ Idema (1981), p. 93.

- ↑ Valentijn (1903), p. 52: quoting Nuyts, Pieter (February 10, 1629)

- ↑ Davidson (1903), p. 13.

- ↑ Campbell, William (1889). An account of missionary success in the island of Formosa: translated from the original Dutch version by Caspar Sibelius, published in London in 1650 and now reprinted with copious appendices, Volume 1. VOL. 1. LONDON 57 LUDGATE HILL: Trübner. pp. 197–198. OCLC 607710307. OL 25396942M. Retrieved Dec 20, 2011.

20 November. – The catechist, Daniel Hendrickx, whose name has been often mentioned, accompanied this expedition to the south, as his great knowledge of the Formosa language and his familiar intercourse with the natives, rendered his services very valuable. On reaching the island of Pangsuy, he ventured—perhaps with overweening confidence in himself— too far away from the others, and was suddenly surrounded by a great number of armed natives, who, after killing him, carried away in triumph his head, arms, legs, and other members, even his entrails, leaving the mutilated trunk behind.

- 1 2 3 Andrade (2005).

- ↑ Keliher (2003), p. 32.

- ↑ Shepherd1993, p. 59.

- ↑ Wills (2000), p. 276.

- ↑ Shepherd 1993, p. 95.

- ↑ Wills (2000), pp. 288-289.

- ↑ Blussé, Leonard (1 January 1989). "Pioneers or cattle for the slaughterhouse? A rejoinder to A.R.T. Kemasang". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 145 (2): 357. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003260.

- ↑ Wills (2010), p. 71.

- ↑ Cook (2007), p. 362.

- ↑ Li (2006), p. 122.

- ↑ Valentijn (1903), p. 75.

- ↑ Knapp (1995), p. 14.

- ↑ van Veen (2003).

- 1 2 3 Roy (2003), p. 15.

- ↑ Hsu, Minna J.; Agoramoorthy, Govindasamy; Desender, Konjev; Baert, Leon; Bonilla, Hector Reyes (August 1997). "Wildlife conservation in Taiwan". Conservation Biology. 11 (4): 834–836. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.011004834.x. JSTOR 2387316.

- ↑ 台灣環境資訊協會-環境資訊中心 (June 30, 2010). "墾丁社頂生態遊 梅花鹿見客 | 台灣環境資訊協會-環境資訊中心". E-info.org.tw. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Glamann (1958).

- ↑ Shepherd (1993), p. 366.

- ↑ Knapp (1995), p. 18.

- 1 2 Roy (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Moffett, Samuel H. (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500-1900. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner Studies in North American Black Religion Series. Volume 2 of A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500-1900. Volume 2 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 1570754500. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Moffett, Samuel H. (2005). A history of Christianity in Asia, Volume 2 (2 ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 1570754500. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Free China Review, Volume 11. W.Y. Tsao. 1961. p. 54. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Newman, Bernard (1961). Far Eastern Journey: Across India and Pakistan to Formosa. H. Jenkins. p. 169. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Wright, Arnold, ed. (1909). Twentieth century impressions of Netherlands India: Its history, people, commerce, industries and resources (illustrated ed.). Lloyd's Greater Britain Pub. Co. p. 67. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Heaver, Stuart (26 February 2012). "Idol worship" (PDF). South China Morning Post. p. 25. Archived from the original on Feb 26, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 4: East Asia. Asia in the Making of Europe Volume III (revised ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 1823. ISBN 0226467694. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 0230614248. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 0230614248. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 0230614248. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 0230614248. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. p. 96. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. p. 96. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Muller, Hendrik Pieter Nicolaas (1917). Onze vaderen in China (in Dutch). P.N. van Kampen. p. 337. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Potgieter, Everhardus Johannes; Buijis, Johan Theodoor; van Hall, Jakob Nikolaas; Muller, Pieter Nicolaas; Quack, Hendrik Peter Godfried (1917). De Gids, Volume 81, Part 1 (in Dutch). G. J. A. Beijerinck. p. 337. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ de Zeeuw, P. (1924). De Hollanders op Formosa, 1624-1662: een bladzijde uit onze kolonialeen zendingsgeschiedenis (in Dutch). W. Kirchner. p. 50. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Algemeene konst- en letterbode, Volume 2 (in Dutch). A. Loosjes. 1851. p. 120. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Volume 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 124. ISBN 900416507X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Volume 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 84. ISBN 900416507X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Volume 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 105. ISBN 900416507X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: Expansion and crisis. Volume 2 of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680 (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0300054122. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hoang, Anh Tuan (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Rerlations ; 1637 - 1700. Volume 5 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 239. ISBN 9004156011. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Kleinen, John; Osseweijer, Manon, eds. (2010). Pirates, Ports, and Coasts in Asia: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. IIAS/ISEAS Series on Maritime Issues and Piracy in Asia (illustrated ed.). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 71. ISBN 9814279072. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Li, Tana (1998). Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. G - Reference,Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series (illustrated ed.). SEAP Publications. p. 173. ISBN 0877277222. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1993). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia. Volume 3 of Asia in the making of Europe: A century of advance (illustrated ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 1380. ISBN 0226467554. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Mazumdar, Sucheta (1998). Sugar and Society in China: Peasants, Technology, and the World Market. Volume 45 of Harvard Yenching Institute Cambridge, Mass: Harvard-Yenching Institute monograph series. Volume 45 of Harvard-Yenching Institute monograph series (illustrated ed.). Harvard Univ Asia Center. p. 90. ISBN 067485408X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2011). History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000-1800 (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9888083341. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Lombard, Denys; Ptak, Roderich, eds. (1994). Asia maritima. Volume 1 of South China and maritime Asia (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 123. ISBN 344703470X. ISSN 0945-9286. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Volker, T. (1954). Porcelain and the Dutch East India Company: As Recorded in the Dagh-Registers of Batavia Castle, Those of Hirado and Deshima and Other Contemporary Papers ; 1602-1682. Volume 11 of Leiden. Rijksmuseum voor volkenkunde. Mededelingen (illustrated ed.). Brill Archive. p. 11. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hoang, Anh Tuan (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Rerlations ; 1637 - 1700. Volume 5 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 210. ISBN 9004156011. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Cheng, Weichung (2013). War, Trade and Piracy in the China Seas (1622-1683). TANAP Monographs on the History of Asian-European Interaction. BRILL. p. 133. ISBN 900425353X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- 1 2 Shepherd (1993).

- ↑ Lee, Yuchung. "荷西時期總論 (Dutch and Spanish period of Taiwan)". Council for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 Chiu (2008), p. 346.

- ↑ Lee, Yuchung. "荷西時期總論 (Dutch and Spanish period of Taiwan)". Council for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- 1 2 Tai (2007), p. 246.

- ↑ Tai, Pao-tsun (2007). The Concise History of Taiwan. Taiwan: Taiwan Historica. ISBN 9789860109504.

- 1 2 Shepherd (1995).

- ↑ Lee, Yuchung. "荷西時期總論 (Dutch and Spanish period of Taiwan)". Council for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Everts (2000), p. 151.

- ↑ Blussé, J.L.; van Opstall, M.E.; Milde, W.E.; Ts'ao, Yung-Ho (1986). De dagregisters van het kasteel Zeelandia, Taiwan 1629-1662 (in Dutch). Den Haag: Inst. voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis. Retrieved December 19, 2014., described in English at "The United East India Company (VOC) in Taiwan 1629-1662". Huygens ING. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ↑ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624 - 1662. Volume 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 222. ISBN 900416507X. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Guo, Elizabeth; Kennedy, Brian. "Tale of Two Towns". News Review. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Sightseeing Introduction to Hongmaocheng" (in Chinese). Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- ↑ Lee, Yuchung. "荷西時期總論 (Dutch and Spanish period of Taiwan)". Council for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2005). How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

- Blussé, Leonard (1984). "Dutch Protestant Missionaries as Protagonists of the Territorial Expansion of the VOC on Formosa". In Kooiman, van den Muijzenburg & van der Veer. Conversion, Competition and Conflict : essays on the role of religion in Asia. Amsterdam: Free University Press. ISBN 9789062560851.

- Blussé, Leonard (1994). "Retribution and Remorse: The Interaction between the Administration and the Protestant Mission in Early Colonial Formosa". In Prakash, Gyan. After Colonialism: Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacement. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691037424.

- Blussé, Leonard (2000). "The Cave of the Black Spirits". In Blundell, David. Austronesian Taiwan. California: University of California. ISBN 9780936127095.

- Blussé, Leonard; Everts, Natalie; Frech, Evelien, eds. (1999). The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa's Aboriginal Society: A Selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources. Vol. I. Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines. ISBN 9579976724.

- Blussé, Leonard; Everts, Natalie, eds. (2000). The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa's Aboriginal Society: A Selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources. Vol. II. Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines. ISBN 9579976775.

- Blussé, Leonard; Everts, Natalie, eds. (2006). The Formosan Encounter: Notes on Formosa's Aboriginal Society: A Selection of Documents from Dutch Archival Sources. Vol. III. Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines. ISBN 9573028735.

- Campbell, William (1996) [1888]. The Gospel of St Matthew in Formosan (Sinkang Dialect) with Corresponding Versions in Dutch and English; Edited from Gravius's Edition of 1661. Taipei, Taiwan: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9576382998. LCCN 2006478012.

- Campbell, William (1903). Formosa under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records. London: Kegan Paul. OCLC 644323041.

- Chiu, Hsin-hui (2008). The Colonial 'Civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa, 1624–1662. Brill. ISBN 9789004165076. OCLC 592756301.

- Cook, Harold John (2007). Matters of Exchange: Commerce, Medicine, and Science in the Dutch Golden Age. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300134926. OCLC 191734183. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Cooper, J. P., ed. (1979). The New Cambridge Modern History IV. The Decline of Spain and the Thirty Years War, 1609-59 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521297134. OCLC 655601868. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Copper, John F. (2003). Taiwan: Nation-State or Province?. Nations of the Modern World (4th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 9780813339559.

- Copper, John F. (2007). Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (3rd ed.). Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810856004.

- Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. ISBN 9780932727909. OCLC 833099470.

- Coyett, Frederick (1675). 't Verwaerloosde Formosa [Neglected Formosa] (in Dutch).

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa Past and Present. London and New York: Macmillan & co. OL 6931635M.

- Deng, Gang (1999). Maritime Sector, Institutions, and Sea Power of Premodern China (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313307126. ISSN 0084-9235. OL 9616521M.

- Everts, Natalie (2000). "Jacob Lamay van Taywan: An Indigenous Formosan Who Became an Amsterdam Citizen". In Blundell, David. Austronesian Taiwan. California: University of California. ISBN 0936127090.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003). Straits of Malacca: Gateway or Gauntlet?. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 077357087X. JSTOR j.ctt7zzph. OCLC 50790090. OL 3357584M. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Goodrich, Luther Carrington; Fang, Chaoying, eds. (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644. 2. Association for Asian Studies. Ming Biographical History Project Committee (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231038331. OCLC 643638442. OL 10195413M.

- Glamann, Kristof (1958). Dutch-Asiatic Trade, 1620–1740. The Hague: M. Nijhoff. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-8361-8. ISBN 9789400983618.

- Heyns, Pol; Cheng, Wei-chung, eds. (2005). Dutch Formosan Placard-book, Marriage, and Baptism Records. Taipei: The Ts'ao Yung-ho Foundation for Culture and Education. ISBN 9867602013.

- Hughes, George (1872). Amoy and the Surrounding Districts: Compiled from Chinese and Other Records. De Souza & Company. OCLC 77480774.

- Idema, Wilt Lukas, ed. (1981). Leyden Studies in Sinology: Papers Presented at the Conference Held in Celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Sinological Institute of Leyden University, December 8-12, 1980. Volume 15 of Sinica Leidensia. Contributor Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden. Sinologisch instituut (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9789004065291. horizontal tab character in

|others=at position 12 (help) - Imbault-Huart, Camille-Clément (1995) [1893]. L'île Formose: Histoire et Déscription (in French). Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9576382912.

- Keliher, Macabe (2003). Out of China or Yu Yonghe's Tales of Formosa: A History of 17th Century Taiwan. Taipei: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9789576386091.

- Knapp, Ronald G. (1995) [1980]. China's Island Frontier: Studies in the Historical Geography of Taiwan. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 957638334X. OCLC 848963435.

- Li, Qingxin (2006). Maritime Silk Road. Translated by William W. Wang. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 9787508509327. OCLC 781420577. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Parker, Edward Harper, ed. (1917). China, Her History, Diplomacy, and Commerce: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day (2 ed.). J. Murray. OCLC 2234675. OL 6603922M.

- Roy, Denny (2003). Taiwan: A Political History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801488054. OL 7849250M.

- Shepherd, John Robert (1993). Statecraft and Political Economy on the Taiwan Frontier, 1600–1800. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804720663. OCLC 25025794.

- Shepherd, John Robert (1995). Marriage and mandatory abortion among the 17th-century Siraya. American Ethnological Society Monograph Series, No. 6. Arlington, Virginia, USA: American Anthropological Association. ISBN 9780913167717. OL 783080M.

- Thomson, Janice E. (1996). Mercenaries, Pirates, and Sovereigns: State-Building and Extraterritorial Violence in Early Modern Europe (reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400821242. JSTOR j.ctt7t30p. OCLC 873012076. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ts'ao, Yung-ho (2006) [1979]. 臺灣早期歷史硏究 [Research into Early Taiwan History] (in Chinese). Taipei: Lianjing. ISBN 9789570806984.

- Ts'ao, Yung-ho (2000). 臺灣早期歷史硏究續集 [Research into Early Taiwan History: Continued] (in Chinese). Taipei: Lianjing. ISBN 9789570821536.

- Twitchett, Denis C.; Mote, Frederick W., eds. (1998). The Cambridge History of China: Volume 8, The Ming Dynasty, Part 2; Parts 1368-1644. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243339. ISBN 9780521243339. OL 25552136M.

- Valentijn, François (1903) [First published 1724 in Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën]. "History of the Dutch Trade". In Campbell, William. Formosa under the Dutch: described from contemporary records, with explanatory notes and a bibliography of the island. London: Kegan Paul. LCCN 04007338.

- van Veen, Ernst (2003). "How the Dutch Ran a Seveenteenth-Century Colony: The Occupation and Loss of Formosa 1624–1662". In Blussé, Leonard. Around and About Formosa. Southern Materials Center. ISBN 9789867602008. OL 14547859M.

- Wills, John E. (2000). "The Dutch Reoccupation of Chi-lung, 1664–1668". In Blundell, David. Austronesian Taiwan. California: University of California. ISBN 9780936127095. OCLC 51641940.

- Wills, John E., Jr. (2010). China and Maritime Europe, 1500–1800: Trade, Settlement, Diplomacy, and Missions. Contributors: John Cranmer-Byng, Willard J. Peterson, Jr, John W. Witek. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511973604. ISBN 1139494260. OL 24524224M. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wright, Arnold (1908). Cartwright, H. A., ed. Twentieth century impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other treaty ports of China: their history, people, commerce, industries, and resources, Volume 1. Lloyds Greater Britain publishing company. OCLC 706078863. OL 13518413M.

Further reading

- Andrade, Tonio (2006). "The Rise and Fall of Dutch Taiwan, 1624–1662: Cooperative Colonization and the Statist Model of European Expansion". Journal of World History. 17 (4): 429–450. doi:10.1353/jwh.2006.0052.

- Valentijn, François (1724–26). Oud en nieuw Oost-Indiën (in Dutch). Dordrecht: J. van Braam. OL 25412097M.

- Wills, John E. Jr. (2005). Pepper, Guns, and Parleys: The Dutch East India Company and China, 1622–1681. Figueroa Press. ISBN 978-1-932800-08-1. OCLC 64281732.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dutch Formosa. |

- Formosa in 17th century

- Dutch Governor of Taiwan (Mandarin)

- Text of the Peace Treaty of 1662

- Exhibition on Dutch period of Taiwan in Tamsui

| Preceded by Prehistory of Taiwan until 1624 |

Dutch Formosa 1624–1662 |

Succeeded by Kingdom of Tungning 1662–1683 |