East Kent Railway

The East Kent Railway (EKR) was an early railway operating between Strood and the town of Faversham in Kent England, during 1858 and 1859. In the latter year it changed its name to the London, Chatham and Dover Railway to reflect its ambitions to build a rival line from London to Dover via Chatham and Canterbury. The line as far as Canterbury was opened in 1860 and the extension to Dover Priory railway station 22 July 1861. The route to Victoria station, London, via the Mid-Kent line and the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway opened on 1 November 1861.

Origins

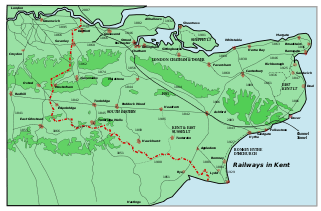

Although it was a relatively prosperous and well-populated area, the north of the county of Kent was poorly served by railways during the 1840s. the South Eastern Railway (SER) had chosen a roundabout southerly route to Dover of 88 miles (142 km), compared to 67 miles (108 km) 'as the crow flies', and had built branches to the main towns in the north of the county from this line. As a result, it was 102 miles (164 km) by the main SER route from London to Margate and Deal although only 75 miles (121 km) by road. The cathedral city of Rochester and the important dockyards of Chatham had no rail link nearer than Strood, on the opposite side of the River Medway. Furthermore, the towns of Faversham, Sittingbourne and the Isle of Sheppey had no railway communication at all. As the SER was then unwilling to undertake new capital projects a large meeting was held at Rochester on 29 January 1850 to discuss the need for a railway connecting Strood to Dover.[1] The idea of a new independent railway was adopted, but lack of financial support meant that it would be three years before any concrete scheme could be proposed.

A plan for the construction of a new railway between the existing stations at Strood and Canterbury was introduced to Parliament in 1853. The scheme also included a branch from Faversham to Faversham Quay on a creek leading to The Swale and a link to the SER at Chilham, together with running powers over the SER North Kent line to London Bridge. There are differing views as to the amount of opposition to the scheme put up by the SER. According to Bradley, the SER ‘exerted great pressure to get the East Kent’s Bill thrown out of Parliament on the grounds of non-compliance with Standing Orders, but a petition by over 9,000 inhabitants of the district persuaded the House of Commons to suspend their Standing Orders and allow the Company to deposit amended plans.[2] One reason for this special treatment was that the line was then 'deemed of great national importance for the defences of the kingdom,’ as it aided the rapid movement of troops and military equipment between the Royal Arsenal, Chatham Dockyard and Dover.[3] The new company did not however gain the running powers requested. Instead, the Act included a facilitations clause which required the SER to handle the EKR traffic ‘as expeditiously as its own between Strood and London Bridge.’[4] At the same time, in return for the minor re-routing of the proposed line at Strood, the EKR received a major concession from the SER in the form of an undertaking to Parliament that they would not oppose any future plan to extend the line to Dover. Permission to build this extension was granted in 1855, before construction work on the initial line had begun. The SER did not put up more opposition as many of the directors felt that the line would never be built due to lack of finance, others ‘waited in the background for the onset of bankruptcy, hoping to absorb the new line at a substantial discount.[5]

Construction of the line

The engineer for the new line was Thomas Russell Crampton who was one of the directors of the new company. The building of the line took an inordinately long time because of the parlous financial state of the EKR throughout is existence. Contracts were not awarded until 1856 and Contractors were often left unpaid. Thus it was not until January 1858 that the line from Chatham to Faversham was completed. The section from Strood, over the river Medway to Chatham was opened in March 1858. This included the Rochester railway bridge designed by Joseph Cubitt. The railway was built as a single track line (with provision for doubling) throughout its 18.5 miles (29.8 km) length and but had taken five years to raise the finance and build. The branch line to Faversham Creek opened 12 April 1860; the main line as far as Canterbury 9 July 1860, reaching Dover town 22 July 1861 and Dover Harbour 1 November 1861.[6] All of these lines were opened after the EKR had changed its name to the London Chatham and Dover Railway. In the event, the links to the SER at Canterbury and Chilham were never built.

Train service

The EKR service was originally five trains per day in each direction, with a journey time of 50 minutes. The railway purchased six 4-4-0ST, LCDR Sondes class Crampton locomotives from R and W Hawthorn. These soon proved to be unreliable and would shortly afterwards had to be rebuilt as conventional 2-4-0Ts.[7]

Westerly extension to the line

In November 1855, soon after gaining authority for the Dover extension, but before it had opened any line, the Company again gave notice of application to Parliament to extend their lines in to both London and Westminster. Their draft proposals involved the construction of fourteen stretches of line involving links with several existing or proposed railways. These included the SER at Dartford, Lewisham and or Greenwich; the London Brighton and South Coast Railway near Deptford; the proposed Westminster Terminus Railway at Manor-Street; and the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway (WEL&CPR) near St Mary Cray. This scatter-gun approach to building new lines into London by a company which was already deeply in debt and was finding it difficult to raise money to complete its existing lines was criticized in the press.[8]

Nevertheless, in 1856 the EKR introduced a Parliamentary Bill seeking running powers over the SER to Dartford, and then to build a new line to link to the proposed Mid Kent line of the West End of London and Crystal Palace Railway. Running powers over the latter railway would then give the EKR access to Battersea Wharf station of the WEL&CPR. The SER successfully fought off this attempt, arguing that their North Kent Line was already operating at full capacity. At one stage they even announced publicly ‘that they would handle no East Kent traffic.’[9]

Proposals by Joseph Locke, Consulting Engineer to the SER, for the amalgamation of that railway and the EKR were discussed by both sides in June 1858, although some of the SER directors were unhappy about taking on such a financially insecure company. Furthermore, under Locke’s proposals, the services of Thomas Crampton, the engineer, contractor and part financier of the Canterbury-Dover line, would be dispensed with. Crampton managed to persuade the EKR board to accept an alternative proposal, that he would finance the westerly extension towards London.[10] The EKR board therefore put forward a revised set of proposals to Parliament in 1858. These involved building their own line from Strood to St Mary Cray where it would connect to the WELCPR at Shortlands (then named Bromley). This plan gave the EKR potential access to Battersea, and later to Victoria station via the Victoria Station & Pimlico Railway. These were accepted and on 1 August 1859 the EKR changed its name to the London Chatham and Dover Railway, before these new lines were completed.[11]

Other lines

Two further railway lines were proposed during the late 1850s with the object of connecting to the EKR, but had not been completed at the time of the change of name. These were: the Sittingbourne and Sheerness Railway which was authorised by Act of Parliament in 1856 and opened 19 July 1860, and the Herne Bay and Faversham Railway which was authorized in 1857 and opened in 1861.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Nock (1961), pp.45-6.

- ↑ Bradley (1979), p.3.

- ↑ London, Chatham, and Dover Railway (1867),p.4.

- ↑ Nock, (1961) p.46.

- ↑ White (1961), p.40.

- ↑ Marshall (1968), p.326.

- ↑ Bradley (1979), pp. 19-20.

- ↑ ‘Railway Intelligence. East Kent’, ‘’The Times’’, 21 November 1855; pg. 5.

- ↑ Nock (1961), p.47.

- ↑ Nock (1961), pp.51-2.

- ↑ White (1961), p.40.

- ↑ Marshall (1968) p.330.

Sources

- Bradley, D. L. (1960). The Locomotives of the London Chatham and Dover Railway. Railway Correspondence and Travel Society.

- Marshall, C. F. Dendy (1968). R.W. Kidner, ed. History of the Southern Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0059-X.

- The London, Chatham, and Dover Railway (main line), Beckenham to Dover: report of the Committee of the main line shareholders, appointed ... 1866. Effingham Wilson. 1867..

- Nock, O. S. (1961). The South Eastern & Chatham Railway. Ian Allan Ltd..

- White, H. P. (1961). A Regional History of the Railways of Southern Great Britain V.2 Southern England. Phoenix House..

External links

- Platform 14 Ltd (2008-05-18). "East Kent Railway". Along These Lines. Season 1. Episode 6. ITV Meridian.