Economy of Cuba

Skyline of Havana | |

| Currency | Cuban peso (CUP) = 100 centavos and Cuban Convertible Peso (CUC) = 24 CUP |

|---|---|

| yes | |

| Statistics | |

| GDP |

$72.3 billion (Nominal) (2012 est.)[1] $121 billion (2012 est.)[2] (PPP) |

| GDP rank | 66th (nominal) / 66th (PPP) |

GDP growth | 4.7% (2015 est.)[3] |

GDP per capita | $10,200 (2010 est.)[2] (PPP) |

GDP by sector | Agriculture: 4%, industry: 23.5%, services: 72.7% (2015 est.)[2] |

| 4.4% (2015 est.)[2] | |

Population below poverty line | 1.5% (2006) |

Labor force | 5.111 million (Public sector: 72.3%, Personal sector: 27.7%) (2015 est.)[2] |

Labor force by occupation | Agriculture: 18%, industry: 10%, services: 72% (2013 est.)[2] |

| Unemployment | 3% (2015 est.)[2] |

Main industries | Sugar, petroleum, tobacco, construction, nickel, steel, cement, agricultural machinery, pharmaceuticals[2] |

| External | |

| Exports | $4.41 billion (2015 est.)[2] |

Export goods | sugar, medical products, nickel, tobacco, shellfish, citrus, coffee[2] |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $15.24 billion (2015 est.)[2] |

Import goods | petroleum, food, machinery and equipment, chemicals[2] |

Main import partners |

|

| Public finances | |

| $25.21 billion (31 December 2014 est.);[2] | |

| Revenues | $2.721 billion (2015 est.) |

| Expenses | $2.919 billion (2015 est.) |

| Economic aid | $87.8 million (2005 est.) |

|

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The Economy of Cuba is a planned economy dominated by state-run enterprises. Most industries are owned and operated by the government and most of the labor force is employed by the state. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, the Communist Party encouraged the formation of cooperatives and self-employment.

In the year 2000, public sector employment was 76% and private sector employment, mainly composed of self-employment, was 23% compared to the 1981 ratio of 91% to 8%.[6] Investment is restricted and requires approval by the government. The government sets most prices and rations goods to citizens. In 2009, Cuba ranked 51st out of 182 countries with a Human Development Index of 0.863; much higher than its GDP per capita rank (95th).[7] In 2012, the country's public debt was 35.3% of GDP. Inflation (CDP) was 5.5%. That year the economy GDP growth was 3%.[8]

Housing and transportation costs are low. Cubans receive free education, health care and food subsidies.[9] Corruption is common,[10][11] although allegedly lower than in most other countries in Latin America.[12]

The country achieved a more even distribution of income since the Revolution and the subsequent economic embargo by the United States. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba's GDP declined by 33% between 1990 and 1993, partially due to loss of Soviet subsidies[13] and to a crash in sugar prices in the early 1990s. Yet Cuba retained relatively high levels of healthcare and education.[14]

History

Before the Revolution

Income inequality was high, accompanied by capital outflows to foreign investors. The country's economy had grown rapidly in the early part of the century, fueled by the sale of sugar to the United States.[15]

Prior to the Cuban Revolution, Cuba was one of the most advanced and successful countries in Latin America.[16] The country compared favorably with Spain and Portugal on socioeconomic measures. By the 1950s Cuba was as rich per capita as Italy was and richer than Japan.[17] Its income per capita in 1929 was reportedly 41% of the US, thus higher than in Mississippi and South Carolina.[18]

Its proximity to the United States made it a familiar holiday destination for wealthy Americans. Their visits for gambling, horse racing and golfing[19] made tourism an important economic sector. Tourism magazine Cabaret Quarterly described Havana as "a mistress of pleasure, the lush and opulent goddess of delights." According to Perez, "Havana was then what Las Vegas has become." [19]

Cuba had a one-crop economy (sugar cane) whose domestic market was constricted. Its population was characterized by chronic unemployment and deep poverty. United States monopolies like Bethlehem Steel Corporation and Speyer gained control over valuable national resources. The banks and the country's entire financial system, all electric power production and the majority of industry was dominated by US companies. US monopolies owned 25 percent of the best land in Cuba. More than 80 percent of farmland was owned by sugar and livestock-raising large landowners. 90 percent of the country's raw sugar and tobacco exports was exported to the US.

In the 1950s, most Cuban children were not in school. 87 percent of urban homes had electricity, but only 10 percent of rural homes did. Only 15 percent of rural homes had running water. Nearly half the rural population was illiterate as was about 25 percent of the total population. Poverty and unemployment in rural areas triggered migration to Havana despite high levels of crime and prostitution.[20] More than 40 percent of the Cuban workforce in 1958 were either underemployed or unemployed. Schools for blacks and mulattoes were inferior to those for whites. Afro-Cubans had the worst living conditions and held the lowest paid jobs.[21]

Cuban Revolution

In 1959, Fidel Castro seized assets valued at 9 Billion American dollars.[22] The current value of the assets seized would be approximately 1.89 trillion dollars at the 11.42% rate of growth that the average US company experienced from 1959 to 2014.[23]

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, citizens were not required to pay a personal income tax (their salaries being regarded as net of any taxes).[24]

During the Revolutionary period Cuba was one of the few developing countries to provide foreign aid to other countries. Foreign aid began with the construction of six hospitals in Peru in the early 1970s.[25] It expanded later in the 1970s to the point where some 8000 Cubans worked in overseas assignments. Cubans built housing, roads, airports, schools and other facilities in Angola, Ethiopia, Laos, Guinea, Tanzania and other countries. By the end of 1985, 35,000 Cuban workers had helped build projects in some 20 Asian, African and Latin American countries.[25]

For Nicaragua in 1982, Cuba pledged to provide over $130 million worth of agricultural and machinery equipment, as well as some 4000 technicians, doctors and teachers.[25]

In 1986 Cuba defaulted on its $10.9 billion debt to the Paris Club. In 1987 Cuba stopped making payments on that debt. In 2002 Cuba defaulted on $750 million in Japanese loans.[26]

Although the Soviet Union offered subsidies to Cuban beginning shortly after the Revolution, comparative economic data from 1989 showed that the amount of Soviet aid was in line with the amount of Western aid to other Latin American countries.[27]

Special Period

The Cuban economy has yet to recover from a decline in gross domestic product of at least 35% between 1989 and 1993 due to the loss of 80% of its trading partners and Soviet subsidies.[28] This loss of subsidies coincided with a collapse in world sugar prices. Sugar had done well from 1985-1990 and crashed precipitously in 1990-1991 and did not recover for five years. Cuba had been insulated from world sugar prices by Soviet price guarantees.

This era was referred to as the "Special Period in Peacetime" later shortened to "Special Period". A Canadian Medical Association Journal paper claimed that "The famine in Cuba during the Special Period was caused by political and economic factors similar to the ones that caused a famine in North Korea in the mid-1990s, on the grounds that both countries were run by authoritarian regimes that denied ordinary people the food to which they were entitled to when the public food distribution collapsed and priority was given to the elite classes and the military."[29] Other reports painted an equally dismal picture, describing Cubans having to resort to eating anything they could find, from Havana Zoo animals to domestic cats.[30] But although the collapse of centrally planned economies in the Soviet Union and other countries of the Eastern bloc subjected Cuba to severe economic difficulties, which led to a drop in calories per day from 3052 in 1989 to 2600 in 2006, mortality rates were not strongly affected thanks to the priority given on maintaining a social safety net.[31]

The government undertook several reforms to stem excess liquidity, increase labor incentives and alleviate serious shortages of food, consumer goods and services. To alleviate the economic crisis, the government introduced a few market-oriented reforms including opening to tourism, allowing foreign investment, legalizing the U.S. dollar and authorizing self-employment for some 150 occupations. (This policy was later partially reversed, so that while the U.S. dollar is no longer accepted in businesses, it remains legal for Cubans to hold the currency.) These measures resulted in modest economic growth. The liberalized agricultural markets introduced in October 1994, at which state and private farmers sell above-quota production at free market prices, broadened legal consumption alternatives and reduced black market prices.

Government efforts to lower subsidies to unprofitable enterprises and to shrink the money supply caused the semi-official exchange rate for the Cuban peso to move from a peak of 120 to the dollar in the summer of 1994 to 21 to the dollar by year-end 1999. The drop in GDP apparently halted in 1994, when Cuba reported 0.7% growth, followed by increases of 2.5% in 1995 and 7.8% in 1996. Growth slowed again in 1997 and 1998 to 2.5% and 1.2% respectively. One of the key reasons given was the failure to notice that sugar production had become uneconomic. Reflecting on the Special period Cuban president Fidel Castro later admitted that many mistakes had been made, "The country had many economists and it is not my intention to criticize them, but I would like to ask why we hadn’t discovered earlier that maintaining our levels of sugar production would be impossible. The Soviet Union had collapsed, oil was costing $40 a barrel, sugar prices were at basement levels, so why did we not rationalize the industry?"[32] Living conditions in 1999 remained well below the 1989 level.

Recovery

Due to the continued growth of tourism, growth began in 1999 with a 6.2% increase in GDP . Growth then picked up, with a growth in GDP of 11.8% in 2005 according to government figures. In 2007 the Cuban economy grew by 7.5%, higher than the Latin American average. Accordingly, the cumulative growth in GDP since 2004 stood at 42.5%.[33][34]

However, from 1996, the State started to impose income taxes on self-employed Cubans.[24]

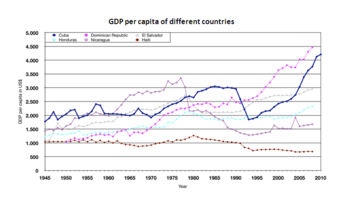

According to Mesa-Lago, Cuba’s economic performance has been overwhelmingly negative. Cuba’s position fell within the region for 87% of those indicators and for the rest remained the same. Cuba ranked third in the region in 1958 in GDP per capita, surpassed only by Venezuela and Uruguay. It had descended to 9th, 11th or 12th place in the region by 2007. Cuban social indicators suffered less.[35]

Post-Fidel reforms

" Either we change course or we sink."

In 2011, "The new economic reforms were introduced, effectively creating a new economic system, referred by some as the "New Cuban Economy"[37][38][39] Since then, over four hundred thousand Cubans have signed up to be entrepreneurs. As of 2012, the government lists 181 official jobs no longer under their control—such as taxi driver, construction worker and shopkeeper. Workers may purchase licenses to work as a mule driver, palm tree trimmer, well-digger, button covered and "dandy"—gentleman in traditional elegant white suit and hat.[40] Despite these openings Cuba maintains nationalized companies for the distribution of all essential amenities (water, power, ...) and other essential services to ensure a healthy population (education, health care).

Imports were double exports and doctors earned £15 per month. Families supplement incomes with extra jobs. After 2000, half the country's sugar mills closed and tourists now ride factory steam locomotives. More than 150,000 farmers lease land from the government for bonus crops. Before, home-owners were allowed to swap properties; legalized buying and selling then created a real-estate boom. In 2012 a Havana fast-food burger pizza restaurant, La Pachanga, started in the owner's home, serves 1,000 meals on a Saturday at £3, the weekly government wage.[41]

In 2008, Raúl Castro's administration hinted that the purchase of computers, DVD players and microwaves would become legal. However, monthly wages remain less than 20 U.S. dollars.[42] Mobile phones, which had been restricted to Cubans working for foreign companies and government officials, were legalized in 2008.[42]

In 2010, Fidel Castro, in agreement with Raúl Castro's reformist sentiment, admitted that the Cuban model based on the old Soviet model of centralized planning was no longer sustainable. They encouraged the creation of a co-operative variant of socialism where the state plays a less active role in the economy and the formation of worker-owned co-operatives and self-employment enterprises.[43]

To remedy Cuba's economic structural distortions and inefficiencies, the Sixth Congress approved expansion of the internal market and access to global markets on April 18, 2011. A comprehensive list of changes is:[44][45]

- Expenditure adjustments (education, healthcare, sports, culture)

- Change in the structure of employment; reduce inflated payrolls and increase work in the non-state sector.

- Legalizing of 201 different personal business licenses

- Fallow state land in usufruct leased to residents

- Incentives for non-state employment, as a re-launch of self-employment

- Proposals for creation of non-agricultural cooperatives

- Legalization of sale and private ownership of homes and cars

- Greater autonomy for state firms

- Search for food self-sufficiency, gradual elimination of universal rationing and change to targeting poorest population

- Possibility to rent state-run enterprises to self-employed, among them state restaurants

- Separation of state and business functions

- Tax policy update

- Easier travel for Cubans

- Strategies for external debt restructuring

On December 20, 2011 a new credit policy allowed Cuban banks to finance entrepreneurs and individuals wishing to make major purchases to do home improvements in addition to farmers. "Cuban banks have long provided loans to farm cooperatives, they have offered credit to new recipients of farmland in usufruct since 2008 and in 2011 they began making loans to individuals for business and other purposes".[46]

The system of rationed food distribution known in Cuba was known as the Libreta de Abastecimiento ("Supplies booklet"). As of 2012 ration books at bodegas still procured rice, oil, sugar and matches, above government average wage £15 monthly.[40]

Raul Castro signed law 313 in September 2013 in order to create a special economic zone in the port city of Mariel, the first in the country.[47]

On 22 October 2013 the dual currency system was set to be ended eventually.[48] As of 2016, the dual currency was still being used in Cuba.

Sectors

Energy production

As of 2011, 96% of electricity was produced from fossil fuels. Solar panels were introduced in some rural areas to reduce blackouts, brownouts and use of kerosene. Citizens were encouraged to swap inefficient lamps with newer models to reduce consumption. A power tariff reduced inefficient use of power.[49]

As of August 2012, off-shore petroleum exploration of promising formations in the Gulf of Mexico had been unproductive with two failures reported. Additional exploration is planned.[50]

In 2007 Cuba produced an estimated 16.89 billion kWh of electricity and consumed 13.93 billion kWh with no exports or imports.[2] In a 1998 estimate, 89.52% of its energy production is fossil fuel, 0.65% is hydroelectric and 9.83% is other production.[2] In both 2007 and 2008 estimates, the country produced 62,100 bbl/d of oil and consumes 176,000 bbl/d with 104,800 bbl/d of imports, as well as 197,300,000 bbl proved reserves of oil.[2] Venezuela is Cuba's primary source of oil.

In 2008 Cuba produced and consumed an estimated 400 million cu m of natural gas, with no cu m of exports or imports and 70.79 billion cu m of provided reserves.[2]

Agriculture

Cuba produces sugarcane, tobacco, citrus, coffee, rice, potatoes, beans and livestock.[2] As of 2015 Cuba imported about 70-80% of its food.[51] and 80-84% of the food it rations to the public.[52] Raúl Castro ridiculed the bureaucracy that shackled the agriculture sector.[52] Before 1959, Cuba boasted as many cattle as people. Today meat is so scarce that it is a crime to kill a cow without government permission.[53] Cuban people suffered from starvation during the Special Period.[29]

Industry

In total, industrial production accounted for almost 37% of Cuban GDP, or US$6.9 billion and employed 24% of the population, or 2,671,440 people, in 1996. A rally in sugar prices in 2009 stimulated investment and development of sugar processing.

In 2003 Cuba's biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry was gaining in importance.[54] Among the products sold internationally are vaccines against various viral and bacterial pathogens. For example, the drug Heberprot-P was developed as a cure for diabetic foot ulcer and had success in many developing countries.[55]

Scientists such as V. Verez-Bencomo were awarded international prizes for their contributions in biotechnology and sugar cane.[56]

Services

Tourism

In the mid-1990s tourism surpassed sugar, long the mainstay of the Cuban economy, as the primary source of foreign exchange. Havana devotes significant resources to building tourist facilities and renovating historic structures. Cuban officials estimate roughly 1.6 million tourists visited Cuba in 1999 yielding about $1.9 billion in gross revenues. In 2000, 1,773,986 foreign visitors arrived in Cuba. Revenue from tourism reached US $1.7 billion.[57] By 2012, some 3M visitors brought nearly £2 billion yearly.[58]

The rapid growth of tourism has had widespread social and economic repercussions. This led to speculation of the emergence of a two-tier economy[59] and the fostering of a state of tourist apartheid. This situation was exacerbated by the influx of dollars during the 1990s, potentially creating a dual economy based on the dollar (the currency of tourists) on the one hand and the peso on the other. Scarce imported goods - and even some of local manufacture, such as rum and coffee- could be had at dollar-only stores, but were hard to find or unavailable at peso prices. As a result, Cubans who earned only in the peso economy, outside the tourist sector, were at a disadvantage. Those with dollar incomes based upon the service industry began to live more comfortably. This widened the gulf between Cubans' material standards of living, in conflict with the Cuban Government's long term socialist policies.[60]

Retail

Cuba has a small retail sector. A few large shopping centers operated in Havana as of September 2012 but charged US prices. Pre-Revolutionary commercial districts were largely shut down. The majority of stores are small dollar stores, bodegas, agro-mercados (farmers' markets) and street stands.[61]

Finance

The financial sector remains heavily regulated and access to credit for entrepreneurial activity is seriously impeded by the shallowness of the financial market.

Foreign investment and trade

The Netherlands receives the largest share of Cuban exports (24%), 70 to 80% of which go through Indiana Finance BV, a company owned by the Van 't Wout family, who have close personal ties with Fidel Castro. Currently, this trend can be seen in other colonial Caribbean communities who have direct political ties with the global economy. Cuba's primary import partner is Venezuela. The second largest trade partner is Canada, with a 22% share of the Cuban export market.[62]

Cuba began courting foreign investment in the Special Period. Foreign investors must form joint ventures with the Cuban government. The sole exception to this rule are Venezuelans, who are allowed to hold 100% ownership in businesses due to an agreement between Cuba and Venezuela. Cuban officials said in early 1998 that 332 joint ventures had begun. Many of these are loans or contracts for management, supplies, or services normally not considered equity investment in Western economies. Investors are constrained by the U.S.-Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act that provides sanctions for those who traffic in property expropriated from U.S. citizens.

Cuba’s average tariff rate is 10 percent. The country’s planned economy deters foreign trade and investment. The state maintains strict capital and exchange controls.[63]

US Dollar

In 1994 the Cuban Government made it legal for its people to possess and use the U.S. dollar. From then until 2004, the dollar came into widespread use in the country. To capture the hard currency flowing into the island through tourism and remittances - estimated at $500–800 million annually - the government set up state-run "dollar stores" throughout Cuba that sold "luxury" food, household and clothing items, compared with basic necessities, which could be bought using the Cuban peso. As such, the standard of living diverged between those who had access to dollars and those without. Jobs that could earn dollar salaries or tips from foreign businesses and tourists became highly desirable. It was common to meet doctors, engineers, scientists and other professionals working in restaurants or as taxicab drivers.

However, in response to stricter economic sanctions by the US and because the authorities were pleased with Cuba's economic recovery, the Cuban government decided in October 2004 to remove the American dollar from circulation. In its place, the Cuban convertible peso is now used, which although not internationally traded, has a value pegged to that of the dollar. A 10% surcharge is levied for conversions from US dollars to the convertible peso; this surcharge does not apply to other currencies, so it acts as an encouragement for tourists to bring currencies such as Euros, pounds sterling or Canadian dollars into Cuba. An increasing number of tourist zones accept Euros.

Owners of small private restaurants (paladares) can seat no more than 12 people[64] and can only employ family members. Set monthly fees must be paid regardless of income earned and frequent inspections yield stiff fines when any of the many self-employment regulations are violated.

As of 2012, more than 150K farmers had signed up to lease land from the government for bonus crops. Before, home-owners were only allowed to swap; once buying and selling were allowed, prices rose.[40]

In cities, "urban agriculture" farms small parcels. Growing organopónicos (organic gardens) in the private sector has been attractive to city-dwelling small producers who sell their products where they produce them, avoiding taxes and enjoying a measure of government help from the Ministry of Agriculture (MINAGRI) in the form of seed houses and advisers.

Poverty

Typical wages range from 400 non-convertible Cuban pesos a month, for a factory worker, to 700 per month for a doctor, or a range of around 17-30 U.S. dollars per month. However, the Human Development Index of Cuba still ranks much higher than the vast majority of Latin American nations.[65] After Cuba lost Soviet subsidies in 1991, malnutrition resulted in an outbreak of diseases.[66] Despite this, the poverty level reported by the government is one of the lowest in the developing world, ranking 6th out of 108 countries, 4th in Latin America and 48th among all countries.[67] Pensions are among the smallest in the Americas at $9.50/month. In 2009, Raúl Castro increased minimum pensions by 2 dollars, which he said was to recompense for those who have "dedicated a great part of their lives to working... and who remain firm in defense of socialism".[68]

Public facilities

- La Bodega – For Cuban nationals only. Redeems coupons for rice, sugar, oil, matches and sells other foodstuffs including rum.[40]

- La Copelia – A government-owned facility offering ice cream, juice and sweets.

- Paladar – A type of small, privately owned restaurant facility with no more than 12 seats.

- La Farmacia – Low-priced medicine, with the lowest costs anywhere in the world.

- Etecsa – National telephone service provider.

- La Feria – A weekly market (Sunday market-type) owned by the government.

- Cervecería Bucanero – A beverage manufacturer, providing both alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages.

- Ciego Montero – The main soft-drink and beverage distributor.

Connection with Venezuela

The relationship cultivated between Cuba and Venezuela in recent years resulted in agreements in which Venezuela provides cheap oil in exchange for Cuban "missions" of doctors to bolster the Venezuelan health care system. Cuba has the second-highest per capita number of physicians in the world (behind Italy). The country sends tens of thousands of doctors to other countries as aid, as well as to obtain favorable trade terms.[69] In nominal terms, the Venezuelan subsidy is higher than whatever subsidy the Soviet Union gave to Cuba,[70] with the Cuban state receiving cheap oil and the Cuban economy receiving around $6 billion annually. According to Mesa-Lago, a Cuban-born US economist. "If this help stops, industry is paralysed, transportation is paralysed and you'll see the effects in everything from electricity to sugar mills," he said.[71]

Economic freedom

In 2014 Cuba’s economic freedom score was 28.7, making its economy one of the world’s least free. Its overall score was 0.2 point higher than last year, with deteriorations in trade freedom, fiscal freedom, monetary freedom and freedom from corruption counterbalanced by an improvement in business freedom. Cuba ranked least free of 29 countries in the South and Central America/Caribbean region and its overall score was significantly lower than the regional average. Over the 20-year history of the Index, Cuba’s economic freedom remained stagnant near the bottom of the “repressed” category. Its overall score improvement was less than 1 point over the past two decades, with score gains in fiscal freedom and freedom from corruption offset by double-digit declines in business freedom and investment freedom.

Despite some progress in restructuring the state sector since 2010, the private sector remained constrained by heavy regulations and tight state controls. Open-market policies were not in place to spur growth in trade and investment and the lack of competition continued to stifle dynamic economic expansion. A watered-down reform package endorsed by the Party trimmed the number of state workers and expanded the list of approved professions, but many details of the reform remained obscure.[63]

Taxes and revenues

As of 2009, Cuba had $47.08 billion in revenues and $50.34 billion in expenditures with 34.6% of GDP in public debt, an account balance of $513 million and $4.647 billion in reserves of foreign exchange and gold.[2] Government spending is around 67 percent of GDP and public debt is around 35 percent of the domestic economy. Despite reforms, the government continues to play a large role in the economy.[63]

The top individual income tax rate is 50 percent. The top corporate tax rate is 30 percent (35 percent for wholly foreign-owned companies). Other taxes include a tax on property transfers and a sales tax. The overall tax burden is 24.4 percent of GDP.[63]

See also

Sources

- Cuba in Transition: Volume 19.

References

- ↑ "Field Listing: GDP (Official Exchange Rate)". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "The World Factbook". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Cuba economic growth rises to 4.7 pct in first half -minister". Reuters. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ↑ "Export Partners of Cuba". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Import Partners of Cuba". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Social Policy at the Crossroads Oxfam America Report

- ↑ UNDP 2009

- ↑ "Cuba Economic Freedom Score" (PDF). Heritage. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ Upside Down World. "Talking with Cubans about the State of the Nation (3/5/04)". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Díaz-Briquets, Sergio; Pérez-López, Jorge (28 June 2010). Corruption in Cuba: Castro and Beyond. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78942-5.

- ↑ "Europeans: come gawp at Cuban poverty!". The Economist. 25 October 2007.

- ↑ Schweimler, Daniel (May 4, 2001). "Cuba's anti-corruption ministry". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- ↑ [Brundenius, Claes (2009) Revolutionary Cuba at 50: Growth with Equity revisited Latin American Perspectives Vol. 36 No. 2 March 2009 pp.31-48]

- ↑ Ritter, Archibald R.M. (9 May 2004). the Cuban Economy. University of Pittsburgh Pre. ISBN 978-0-8229-7079-8.

- ↑ [Mehrotra, Santosh. (1997) Human Development in Cuba: Growing Risk of Reversal in Development with a Human Face: Experience in Social Achievement and Economic Growth Ed. Santosh Mehrotra and Richard Jolly, Clarendon Press, Oxford]

- ↑ "American Experience - Fidel Castro - People & Events - PBS". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "History News Network - Humberto Fontova: Historians Have Absolved Fidel Castro". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Marianne Ward (Loyola College) and John Devereux (Queens College CUNY), The Road not taken: Pre-Revolutionary Cuban Living Standards in Comparative Perspective pp. 30-31.

- 1 2 Natasha Geiling. "Before the Revolution". Smithsonian. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Gjelten, Tom (2008). Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba: The Biography of a Cause. Viking. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-670-01978-6. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Brenner, Philip (2008). A Contemporary Cuba Reader: Reinventing the Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-7425-5507-5. Retrieved March 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Cuba After Castro: Can Exiles Reclaim Their Stake?". TIME.com. 5 August 2006. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Returns Investing Calculator | Bankrate.com". www.bankrate.com. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- 1 2 New York Times (November 1995). "Well-to-Do in Cuba to Pay an Income Tax". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- 1 2 3 "CUBA TODAY". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Investor's Business Daily". Investor's Business Daily. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ "Cuba's Revolutionary Economy". multinationalmonitor.org. April 1989. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

Soviet aid to Cuba in per capita terms or as a share of national income is in line with the amount of Western aid to many Latin American countries.

- ↑ John Pike. "Cuba's Economy". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- 1 2 "Health Consequences of Cuba's Special Period". Canadian Medical Association Journal. July 29, 2008.

- ↑ "Parrot diplomacy". The Economist. July 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Cuba's Organic Revolution". TreeHugger. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Content Not Found - Mail & Guardian". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ granma.cu - Cuban Economy Grows 7.5 Per Cent Archived February 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "CHALLENGES 2007-2008: Cuban Economy in Need of Nourishment". Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Mesa-Lago, Carmelo. Economic and Social Balance of 50 Years of Cuban Revolution (PDF). p. 371, 380. in CIT

- ↑ Voss, Michael (April 16, 2011). "A last hurrah for Cuba's communist rulers". BBC News. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ↑ "Cuba adopta nuevos lineamientos económicos para aumentar la producción". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Cuba's Coming Co-operative Economy? - Global Research - Centre for Research on Globalization". Global Research. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ New Cuban Economy

- 1 2 3 4 "BBC 2012 Simon Reeve documentary". Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ "BBC Simon Reeve 2012 documentary". Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Cell phones, microwaves: New access to gizmos could deflect calls for deeper change in Cuba". International Herald Tribune. March 28, 2008.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Stephen (September 10, 2010). "Cuba: from communist to co-operative? – Stephen Wilkinson". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Domínguez, Jorge I. (2012). Cuban Economic and Social Development: Policy Reforms and Challenges in the 21st Century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06243-6.

- ↑ Perez Villanueva, Omar Evernly; Pavel Vidal Alejandro (2010). "Cuban Perspectives on Cuban Socialism". The Journal of the Research on Socialism and Democracy". 24 (1).

- ↑ Philip, Peters (23 May 2012). "A Viewers Guide to Cuba's Economic Reforms". Lexington Institute: 21.

- ↑ Chris Arsenault. "Cuba to open tax free Special Economic Zone". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Cuba to scrap two-currency system in latest reform". BBC News. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ Laurie Guevara-Stone "La Revolucion Energetica: Cuba's Energy Revolution", Renewable Energy World International Magazine, 9 April 2009.

- ↑ "2nd Cuban offshore oil well also a bust". The Guardian. Havana. AP Foreign. August 6, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ↑ "WFP Cuba page".

- 1 2 "Cuban leader looks to boost food production". CNN. April 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Fifty years of the Castro regime - Time for a (long overdue) change". The Economist. December 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Truly revolutionary". The Economist. 29 November 2003.

- ↑ "Ecuadorians benefit from Cuban drug Heberprot-p". Radio Havana Cuba. 2012-08-12. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ↑ Gorry, C. "Dr vicente vérez bencomo, director, center for the study of synthetic antigens, university of havana.". PubMed.gov.

- ↑ "Tourism, travel, and recreation - Cuba". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ BBC 2012 SimonReeve on YouTube

- ↑ Tourism in Cuba during the Special Period

- ↑ Lessons From Cuba Travel Outward

- ↑ "Cuba". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ FAQs on Canada-Cuba trade CBC

- 1 2 3 4 "2014 Index of Economic Freedom". www.heritage.org. The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ↑ P. J. O'Rourke (1 December 2007). Eat the Rich: A Treatise on Economics. Grove/Atlantic, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-55584-710-4.

- ↑ "Cuba - The comandante's last move". The Economist. February 21, 2008.

- ↑ Efrén Córdova. "The situation of Cuban workers during the "Special Period in peacetime"" (PDF).

- ↑ List of countries by Human Development Index#Complete list of countries

- ↑ "Raul Castro raises state pension". BBC. April 27, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ↑ Tamayo, Juan O. "How will the Venezuela-Cuba link fare after Chávez's death?". miamiherald. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Jeremy Morgan. "Venezuela's Chávez Fills $9.4 Billion Yearly Post-Soviet Gap in Cuba's Accounts". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ↑ "As Hugo Chavez fights for his life, Cuba fears for its future". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

External links

- Cuba's Economic Struggles from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- The Road not taken: Pre-Revolutionary Cuban Living Standards in Comparative Perspective, Marianne Ward (Loyola College) and John Devereux (Queens College CUNY)

- ARCHIBOLD, RANDAL. Inequality Becomes More Visible in Cuba as the Economy Shifts (February 2015), The New York Times

- Cave, Danien. Raúl Castro Thanks U.S., but Reaffirms Communist Rule in Cuba (December 2014), The New York Times. "Mr. Castro prioritized economics. He acknowledged that Cuban state workers needed better salaries and said Cuba would accelerate economic changes in the coming year, including an end to its dual-currency system. But he said the changes needed to be gradual to create a system of “prosperous and sustainable communism.”"

- Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana