Emotional Freedom Techniques

| Alternative medicine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Claims | Tapping on "meridian points" on the body, derived from acupuncture, can release "energy blockages" that cause "negative emotions"[1] |

| Related fields | Acupuncture, Acupressure, Energy medicine |

| Year proposed | 1993 |

| Original proponents | Gary Craig |

| Subsequent proponents | Jack Canfield, Nick Ortner |

| See also | Thought Field Therapy, Tapas Acupressure Technique |

Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) is a form of counseling intervention that draws on various theories of alternative medicine including acupuncture, neuro-linguistic programming, energy medicine, and Thought Field Therapy (TFT). It is best known through Gary Craig's EFT Handbook, published in the late 1990s, and related books and workshops by a variety of teachers. EFT and similar techniques are often discussed under the umbrella term "energy psychology".

Advocates claim that the technique may be used to treat a wide variety of physical and psychological disorders, and as a simple form of self-administered therapy.[1] The Skeptical Inquirer describes the foundations of EFT as "a hodgepodge of concepts derived from a variety of sources, [primarily] the ancient Chinese philosophy of chi, which is thought to be the 'life force' that flows throughout the body." The existence of this life force is "not empirically supported".[2]

EFT has no benefit as a therapy beyond the placebo effect or any known-effective psychological techniques that may be provided in addition to the purported "energy" technique.[3] It is generally characterized as pseudoscience and has not garnered significant support in clinical psychology.

Process

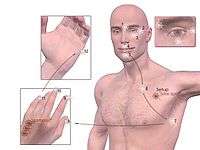

During a typical EFT session, the person will focus on a specific issue while tapping on "end points of the body's energy meridians".

According to the EFT manual, the procedure consists of the participant rating the emotional intensity of their reaction on a Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) (a Likert scale for subjective measures of distress, calibrated 0-10) then repeating an orienting affirmation while rubbing or tapping specific points on the body. Some practitioners incorporate eye movements or other tasks. The emotional intensity is then rescored and repeated until no changes are noted in the emotional intensity.[1]

Mechanism

Proponents of EFT and other similar treatments believe that tapping/stimulating acupuncture points provide the basis for significant improvement in psychological problems.[4] However, the theory and mechanisms underlying the supposed effectiveness of EFT have "no evidentiary support" "in the entire history of the sciences of biology, anatomy, physiology, neurology, physics, or psychology." Researchers have described the theoretical model for EFT as "frankly bizarre" and "pseudoscientific."[3] One review noted that one of the highest quality studies found no evidence that the location of tapping points made any difference, and attributed effects to well-known psychological mechanisms, including distraction and breathing therapy.[3][5]

An article in the Skeptical Inquirer argued that there is no plausible mechanism to explain how the specifics of EFT could add to its effectiveness, and they have been described as unfalsifiable and therefore pseudoscientific.[2] Evidence has not been found for the existence of meridians.[6]

Research quality

EFT has no useful effect as a therapy beyond the placebo effect or any known-effective psychological techniques that may be used with the purported "energy" technique, but proponents of EFT have published material claiming otherwise. Their work, however, is flawed and hence unreliable: high-quality research has never confirmed that EFT is effective.[3]

A 2009 review found "methodological flaws" in research studies that had reported "small successes" for EFT and the related Tapas Acupressure Technique. The review concluded that positive results may be "attributable to well-known cognitive and behavioral techniques that are included with the energy manipulation. Psychologists and researchers should be wary of using such techniques, and make efforts to inform the public about the ill effects of therapies that advertise miraculous claims."[7]

Reception

A Delphi poll of an expert panel of psychologists rated EFT on a scale describing how discredited EFT has been in the field of psychology. On average, this panel found EFT had a score of 3.8 on a scale from 1.0 to 5.0, with 3.0 meaning "possibly discredited" and a 4.0 meaning "probably discredited."[8] A book examining pseudoscientific practices in psychology characterized EFT as one of a number of "fringe psychotherapeutic practices",[9] and a psychiatry handbook states EFT has "all the hallmarks of pseudoscience".[10]

EFT, along with its predecessor, Thought Field Therapy, has been dismissed with warnings to avoid their use by publications such as the The Skeptic's Dictionary[11] and Quackwatch.[12]

Proponents of EFT and other energy psychology therapies have been "particularly interested" in seeking "scientific credibility" despite the implausible proposed mechanisms for EFT.[3] A 2008 review by energy psychology proponent David Feinstein concluded that energy psychology was a potential "rapid and potent treatment for a range of psychological conditions."[13] However, this work by Feinstein has been widely criticized. One review criticized Feinstein's methodology, noting he ignored several research papers that did not show positive effects of EFT, and that Feinstein did not disclose his conflict of interest as an owner of a website that sells energy psychology products such as books and seminars, contrary to the best practices of research publication.[14] Another review criticized Feinstein's conclusion, which was based on research of weak quality and instead concluded that any positive effects of EFT are due to the more traditional psychological techniques rather than any putative "energy" manipulation.[7] A book published on the subject of evidence based treatment of substance abuse called Feinstein's review "incomplete and misleading" and an example of a poorly performed evidence based review of research.[15]

Feinstein published another review in 2012, concluding that energy psychology techniques "consistently demonstrated strong effect sizes and other positive statistical results that far exceed chance after relatively few treatment sessions".[4] This review was also criticized, where again it was noted that Feinstein dismissed higher quality studies which showed no effects of EFT, in favor of methodologically weaker studies which did show a positive effect.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Craig, G (n.d.). EFT Manual (pdf). Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- 1 2 Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD (2000). "Can we really tap our problems away?". Skeptical Inquirer. 24 (4). Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bakker, Gary M. (November 2013). "The current status of energy psychology: Extraordinary claims with less than ordinary evidence". Clinical Psychologist. 17 (3): 91–99. doi:10.1111/cp.12020.

- 1 2 Feinstein, David (December 2012). "Acupoint stimulation in treating psychological disorders: Evidence of efficacy". Review of General Psychology. 16 (4): 364–380. doi:10.1037/a0028602.

- ↑ Waite, Wendy L; Holder, Mark D (2003). "Assessment of the Emotional Freedom Technique". Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice. 2 (1).

- ↑ Singh, S; Ernst E (2008). "The Truth about Acupuncture". Trick or treatment: The undeniable facts about alternative medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 39–90. ISBN 978-0-393-06661-6.

"Scientists are still unable to find a shred of evidence to support the existence of meridians or Ch'i" (p72), "The traditional principles of acupuncture are deeply flawed, as there is no evidence at all to demonstrate the existence of Ch'i or meridians" (p107)

- 1 2 McCaslin DL (June 2009). "A review of efficacy claims in energy psychology". Psychotherapy (Chicago). 46 (2): 249–56. doi:10.1037/a0016025. PMID 22122622.

- ↑ Norcross, John C.; Koocher, Gerald P.; Garofalo, Ariele (1 January 2006). "Discredited psychological treatments and tests: A Delphi poll.". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 37 (5): 515–522. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.515.

- ↑ Lilienfeld, Scott O. (2003). Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (Paperback ed.). New York [u.a.]: Guilford Press. p. 2. ISBN 1-57230-828-1.

- ↑ Semple, David (2013). Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-19-969388-7.

- ↑ "Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT)". Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Barrett, Stephen. "Mental Help: Procedures to Avoid". Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Feinstein, D (Jun 2008). "Energy psychology: A review of the preliminary evidence.". Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.). 45 (2): 199–213. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.199. PMID 22122417.

- ↑ Pignotti, M; Thyer, B (Jun 2009). "Some comments on "Energy psychology: A review of the evidence": Premature conclusions based on incomplete evidence?". Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.). 46 (2): 257–61. doi:10.1037/a0016027. PMID 22122623.

- ↑ editors, Katherine van Wormer, Bruce A. Thyer, (2010). Evidence-based practice in the field of substance abuse : a book of readings. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage. p. 2. ISBN 1412975778.